Science

The amazing story of Reggie, L.A.’s celebrity alligator

Reggie, probably the most well-known alligator in Los Angeles, lives in a fantastically landscaped midcentury dwelling simply outdoors Los Feliz. When it’s sunny, he swims in his pool. When it’s chilly, he doesn’t do a lot of something. He lives companionably with a feminine named Tina, and should you assume it’s simple for 2 alligators to pair up later in life with out attempting to chunk one another’s limbs off, effectively, you don’t know rather a lot about alligators.

Between the 2 fences that separate Reggie’s enclosure from the general public is an indication with the thumbnail model of his outstanding journey to the Los Angeles Zoo 15 years in the past immediately. Some guests cease to learn it; numerous them don’t. However as soon as upon a time — earlier than P-22, earlier than Grumpy Cat and Doug the Pug — individuals gathered by the tons of simply to catch a glimpse of the celeb gator.

You can purchase T-shirts emblazoned with Reggie’s likeness. His identify appeared in headlines from Lengthy Seaside to London. An honest chunk of L.A.’s finances — $180,000 — went to Reggie-related bills.

What Reggie makes of his uncommon life story is a thriller. An alligator mind is the scale of a peanut.

In June 2006, metropolis employee Neal Weeks appears to be like out over Lake Machado for Reggie the Alligator, who was set unfastened at Ken Malloy Harbor Regional Park.

(Nick Ut / Related Press)

A Gator emerges

Lake Machado immediately is the enticing middle of Ken Malloy Harbor Regional Park in Harbor Metropolis, a haven for birds and native vegetation. However in the summertime of 2005, the lake was a polluted watering gap, encircled with overgrown vegetation and teeming with frogs, birds and carp.

There is no such thing as a good place in Los Angeles to set an alligator free. That stated, Lake Machado at the moment was not the worst place to do it. Reggie was positioned there by two reptile fanatics who’d raised him of their San Pedro properties, alongside snapping turtles, piranhas, rattlesnakes and desert tortoises.

Pet alligators are unlawful in California, however they’re not laborious to come back by. Hatchlings have huge eyes, snubby little snouts and may match within the palm of your hand.

An alligator is seen cruising Lake Machado on Aug. 12, 2005.

(Chuck Bennett / Day by day Breeze)

A ten-year-old American alligator, however, might be 6 ft lengthy and powerful sufficient to chunk by bone.

Someplace in between is when numerous unique pet homeowners attain the identical conclusion that Reggie’s former handlers did: The gator needed to go.

Alligators, although, are nothing if not survivors.

Crocodilian reptiles appeared on the planet alongside dinosaurs some 95 million years in the past and have held on ever since. Fossils present that the type of the American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) has remained nearly unchanged within the final 8 million years, as if it had merely opted out of evolution.

Gators are the semiaquatic equal of coyotes, stated Ian Recchio, the zoo’s reptile curator: canny, omnivorous, adept at snatching meals and avoiding predators.

“It virtually grew to become a circus-like ambiance. Significantly within the night when Reggie might be seen poking his head out of the lake, they might convey garden chairs and blankets.”

— Supervisor Janice Hahn, then a metropolis councilwoman representing Harbor Metropolis

Rumors of an alligator-like determine surfacing within the lake started to swirl round Harbor Metropolis. This was a yr and a half earlier than the iPhone, and photographic proof was scarce. Claims of a wild swamp-dwelling reptile residing a mile from the 110 appeared fantastical.

Then on Aug. 12, a teenage Reggie crawled out of the water for a sunbath, and a metropolis misplaced its thoughts.

Chaos ensues

Park workers shortly constructed a fence across the lake. After that, nobody actually appeared positive what to do.

Curious crowds gathered on the park. The longer Reggie remained on the unfastened, the extra individuals got here. English-speaking followers nicknamed the alligator Harry; Spanish audio system known as him Carlito. Folks hurled choices of meals over the fence: marshmallows, uncooked rooster, tortillas. Distributors patrolled the gang with custom-designed T-shirts and snacks.

A crowd at Lake Machado on Sept. 28, 2005, hoping to catch a glimpse of Reggie.

(Ted Soqui / Getty Pictures)

From the shore, Reggie gave the impression to be about six ft lengthy. He’s seen right here in Could 2007 in Lake Machado.

(Brad Graverson / Day by day Breeze)

“It virtually grew to become a circus-like ambiance,” stated Los Angeles County Supervisor Janice Hahn, then a metropolis councilwoman representing Harbor Metropolis. “Significantly within the night, when Reggie might be seen poking his head out of the lake, they might convey garden chairs and blankets.”

From a distance, the animal gave the impression to be about 6 ft lengthy. It was laborious to find out its species or intercourse. Authorities assumed it was a former pet, owned illegally and launched into the waters when it bought too huge to deal with.

Column One

A showcase for compelling storytelling from the Los Angeles Occasions.

“I imply, they’re cute once they’re infants,” stated Jay Younger, supervisor of Colorado Gators Reptile Park. “However so was I, and look how that turned out.”

Younger was the primary in a line of colourful gator wranglers who tried to rescue Reggie from the park. Information studies described him as a swashbuckling reptile skilled who rolled into city in an alligator-tooth necklace.

“I had tooth in my hat too,” he stated.

A boater cruises Lake Machado in September 2005, with Reggie nonetheless on the unfastened.

(Ted Soqui / Getty Pictures)

Younger didn’t catch the alligator, and for a very long time, neither did anybody else.

After Younger got here a staff from Gatorland, an Orlando, Fla., theme park and wildlife protect. They left empty-handed, and the town employed Thomas “T-Bone” Quinn, a self-proclaimed alligator wrangler from Louisiana. That provide was rescinded 24 hours later when it emerged that Quinn had no insurance coverage and no credentials. (He was arrested on a parole violation three months later.)

Information of L.A.’s elusive alligator reached Steve Irwin, the Australian zookeeper and star of the worldwide hit TV sequence “The Crocodile Hunter.”

“It’s like a needle in a haystack, besides the needle can transfer any path at 30 miles an hour.”

— Jay Younger, supervisor of Colorado Gators Reptile Park

Irwin flew out to Los Angeles on a scouting journey in summer time 2006, Hahn stated, and pledged to come back again within the spring together with his digital camera crew. Solely weeks later, Irwin was killed by a short-tail stingray.

As chaos reigned on the lake, an nameless tip led police to the 2 San Pedro males who admitted to releasing the animal into the lake after he outgrew enclosures at their properties. They gave the police some helpful intel: They’d named the gator Reggie.

LAPD First Assistant Chief Jim McDonnell holds up a photograph of Reggie the Alligator at an August 2005 information convention.

(Kevork Djansezian / Related Press)

“We have now animals at our park that we work with on a regular basis. They know their identify,” a Gatorland wrangler advised a Occasions reporter. “We go on the market and say, ‘Hey Bob, come right here, Bob, over right here,’ and he’ll come proper as much as you.”

It’s not that Reggie was a very canny alligator, craftily outwitting his would-be captors. He was only a common alligator, behaving as an alligator would in a setting much more suited to his wants than to these of his pursuers.

The percentages had been all the time in Reggie’s favor. The lake was the scale of 15 Costcos. Meals was considerable. If Reggie perceived a sound or motion as threatening, he merely swam away.

Lake Machado was so amenable to alligators that firefighters discovered a second gator in an adjoining flood channel in the course of the search, one too small to be Reggie. It was quietly transferred to an animal sanctuary whereas the pursuit continued.

“It’s like a needle in a haystack, besides the needle can transfer any path at 30 miles an hour,” Younger stated. The much less commotion there may be right here, extra seemingly we’re going to see it.”

However there was all the time commotion. The crowds across the lake had been near-constant, which meant any gator-hunting efforts occurred in full view of an viewers. Media helicopters chopped overhead, scaring Reggie again into the water earlier than wranglers might seize him.

Ramon, left, and his spouse, Minela, stroll their canine Maya round Ken Malloy Harbor Regional Park in June 2006.

(Nick Ut / Los Angeles Occasions)

“It was the largest fiasco I’d ever seen,” recalled Flavio Morrissiey, a member of the Gatorland crew. “It wasn’t that huge! We’d not take into account {that a} risk. However I assume in California you’d take into account that information.”

The gator is captured

Winter got here, and Reggie disappeared.

As temperatures fall, alligators’ metabolism plummets; they eat and transfer a lot much less. They have an inclination to spend this susceptible interval sheltering on land or underwater, the place they’ll keep as much as an hour with out arising for air.

On Could 24, 2007, a number of weeks after his first confirmed sighting in additional than a yr, Reggie crawled out of the water to solar himself on a financial institution simply contained in the chain-link fence. It was the very best shot but at his seize.

Animal management officers and L.A. Zoo officers carry an alligator captured Could 24, 2007 at Lake Machado into the zoo.

(Sean Hiller / Day by day Breeze)

Recchio rushed to the park and located a 7½-foot-long alligator sturdy and lean from life within the wild. Reggie was cornered, and was as agitated as a younger male alligator might be.

This, Recchio realized, was not a one-person job. He turned to a huddle of younger, burly park workers.

“I stated, ‘Have you ever ever watched “The Croc Hunter?” And one of many guys goes, ‘Yeah,’” Recchio stated. He had his wingman.

Column One

A showcase for compelling storytelling from the Los Angeles Occasions.

Recchio scaled the fence and secured Reggie’s head with a dog-catching pole lent to him by animal management. The park worker adopted, and collectively they pinned the gator to the bottom. With the assistance of a second daring park worker, Recchio duct-taped the gator’s jaws and wrapped a T-shirt round his eyes.

Then they lay there, three males and a gator, till firefighters arrived with a backbone board sturdy sufficient to help the renegade reptile.

Reggie was loaded into an animal management truck for the 30-mile journey to the zoo. TV stations carried stay footage of the journey.

The gator in captivity

As soon as on the zoo, Reggie was handled for parasites and positioned into quarantine. Checks confirmed the long-held assumption that he was male. A vacant enclosure previously occupied by flamingos was deemed a perfect alligator habitat.

On his first day earlier than the general public, Reggie was greeted by a cheering crowd. He crept into the wading pool and hid behind a rock.

Reggie the Alligator in his enclosure on the L.A. Zoo in Could 2022.

(Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Occasions)

Reggie nonetheless has his admirers, however the enormous crowds have light away.

(Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Occasions)

On the sixth day, he escaped.

Reggie had completed in his new habitat what he most certainly had completed upon getting into Lake Machado. He explored his environment. He regarded for meals and locations to cover. He checked for different alligators which may desire a piece of his territory.

It was August, and the coldblooded animal’s vitality was at its peak. When Reggie got here to a chain-link fence greater than 4 ft tall — one which “alligators actually shouldn’t have the ability to recover from,” Recchio stated — he began climbing.

Zoo workers making the morning rounds discovered an empty alligator enclosure round 7:30 a.m. “That’s clearly a giant deal,” Recchio stated.

Fortuitously, alligators are rather a lot simpler to trace on land. Reptile curators adopted the path of tail-drag marks and gator footprints (5 toes on the entrance ft, 4 webbed ones on the again) to a loading dock about 500 yards away the place Reggie had paused to relaxation.

He quickly returned to public view, behind a taller fence. And there he has remained.

In 2010, the zoo launched Reggie to Cajun Kate, an American alligator beforehand positioned in a special enclosure. Newspapers celebrated the “life companions.”

Reggie now lives with Tina, a feminine companion on the L.A. Zoo.

(Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Occasions)

The fact of alligator relationships is much more sophisticated.

Alligators raised collectively in captivity can usually cohabitate peacefully. Making an attempt to introduce an grownup alligator into one other’s territory is sort of all the time a catastrophe. “Reggie tried to kill her,” Recchio stated, and Kate was despatched to an animal sanctuary in Florida.

The zoo tried once more in 2016 with Tina, an American alligator outgrowing her lodgings on the Pasadena Humane Society. Each animals confirmed aggressive behaviors to the opposite at first. However as winter approached and their metabolism slowed, they relaxed. When spring got here round, the pair appeared comfy with one another. Reggie likes Tina and hisses protectively at individuals who get near her.

There’s a surplus of American alligators within the U.S., so the zoo is adamant that no infants will come from this pair. Have been Tina to put fertilized eggs, which she has by no means completed, they might be eliminated and destroyed.

That stated, Reggie and Tina are for probably the most half free to behave towards each other as any male-female pair of alligators would. No mating has been witnessed, however it could actually’t be dominated out. Reptiles typically favor to breed late at night time or within the early morning hours.

Even probably the most public of alligators have personal lives.

Reggie and Tina.

(Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Occasions)

Coda

Reggie is now about 8 ft lengthy and 250 kilos. He’s in all probability round 30 years outdated and will stay 50 extra years in captivity.

There are dozens of how Reggie’s story might have ended, virtually all of them unhealthy. He might have been sickened or killed within the lake. He might have harmed a pet or an individual. Don’t anticipate issues to end up superb should you set an alligator unfastened in a public park.

Reggie by no means requested for any of this.

He’s as alligator-like as alligators come, Recchio likes to say. The one factor that makes him totally different is that for some time, he was a star in L.A.

Science

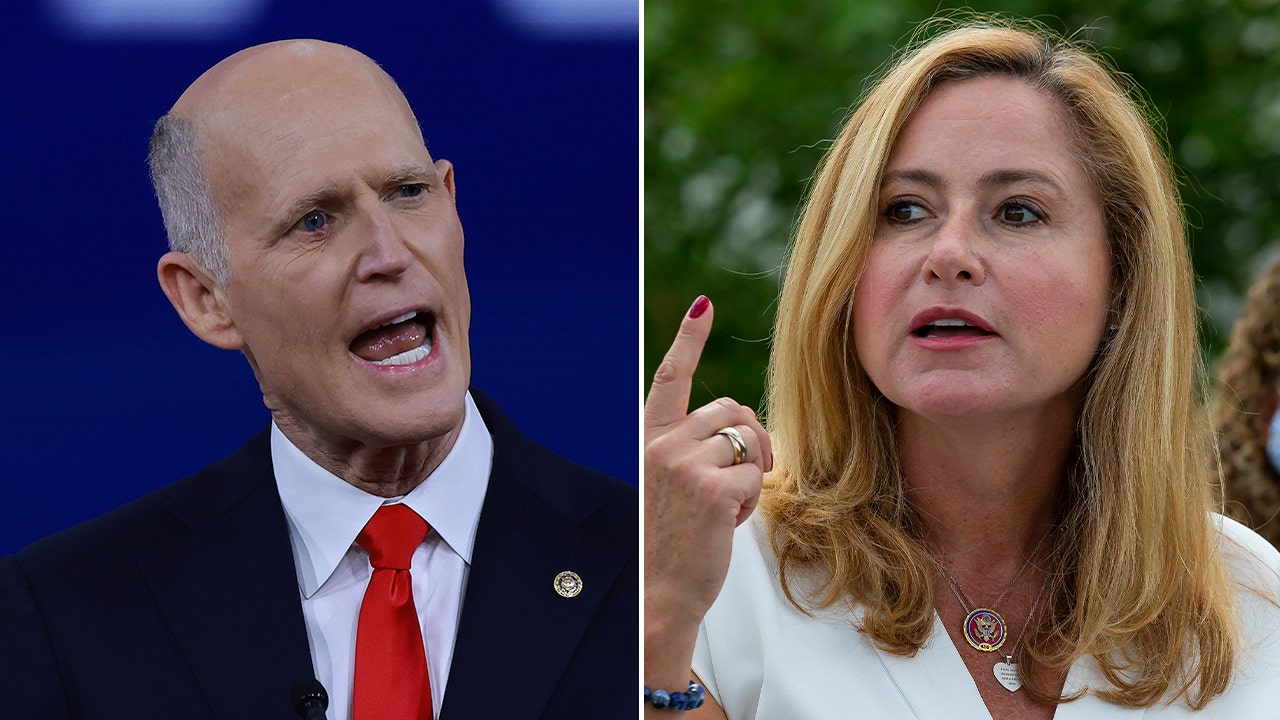

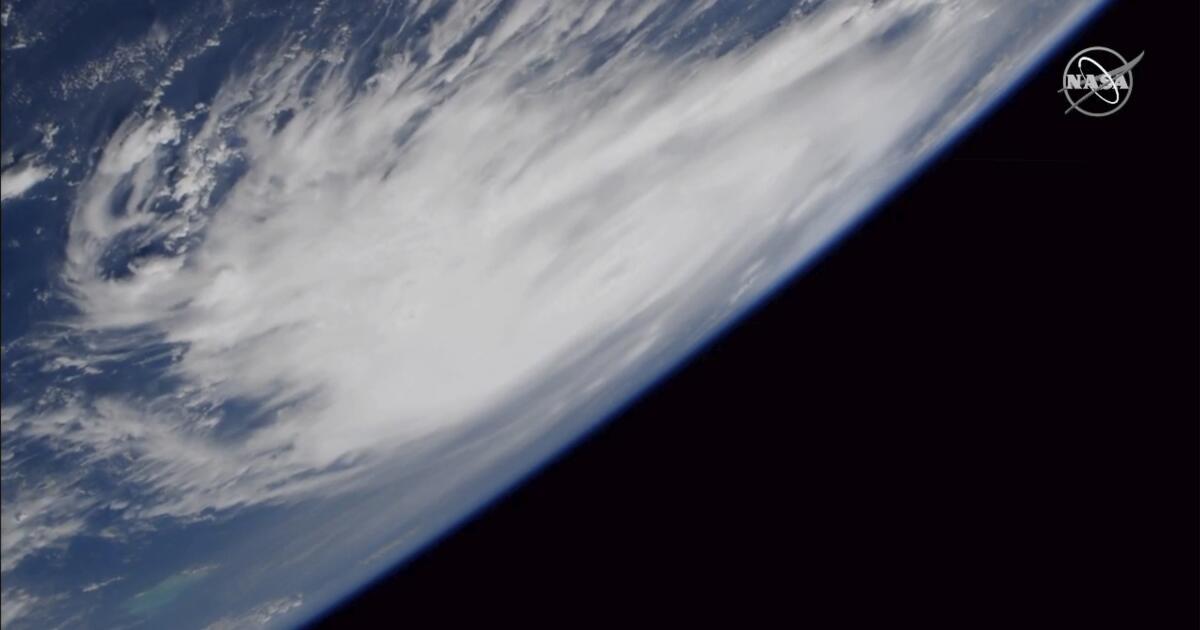

You're gonna need a bigger number: Scientists consider a Category 6 for mega-hurricane era

In 1973, the National Hurricane Center introduced the Saffir-Simpson scale, a five-category rating system that classified hurricanes by wind intensity.

At the bottom of the scale was Category 1, for storms with sustained winds of 74 to 95 mph. At the top was Category 5, for disasters with winds of 157 mph or more.

In the half-century since the scale’s debut, land and ocean temperatures have steadily risen as a result of greenhouse gas emissions. Hurricanes have become more intense, with stronger winds and heavier rainfall.

With catastrophic storms regularly blowing past the 157-mph threshold, some scientists argue, the Saffir-Simpson scale no longer adequately conveys the threat the biggest hurricanes present.

Earlier this year, two climate scientists published a paper that compared historical storm activity to a hypothetical version of the Saffir-Simpson scale that included a Category 6, for storms with sustained winds of 192 mph or more.

Of the 197 hurricanes classified as Category 5 from 1980 to 2021, five fit the description of a hypothetical Category 6 hurricane: Typhoon Haiyan in 2013, Hurricane Patricia in 2015, Typhoon Meranti in 2016, Typhoon Goni in 2020 and Typhoon Surigae in 2021.

Patricia, which made landfall near Jalisco, Mexico, in October 2015, is the most powerful tropical cyclone ever recorded in terms of maximum sustained winds. (While the paper looked at global storms, only storms in the Atlantic Ocean and the northern Pacific Ocean east of the International Date Line are officially ranked on the Saffir-Simpson scale. Other parts of the world use different classification systems.)

Though the storm had weakened to a Category 4 by the time it made landfall, its sustained winds over the Pacific Ocean hit 215 mph.

“That’s kind of incomprehensible,” said Michael F. Wehner, a senior scientist at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and co-author of the Category 6 paper. “That’s faster than a racing car in a straightaway. It’s a new and dangerous world.”

In their paper, which was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Wehner and co-author James P. Kossin of the University of Wisconsin–Madison did not explicitly call for the adoption of a Category 6, primarily because the scale is quickly being supplanted by other measurement tools that more accurately gauge the hazard of a specific storm.

“The Saffir-Simpson scale is not all that good for warning the public of the impending danger of a storm,” Wehner said.

The category scale measures only sustained wind speeds, which is just one of the threats a major storm presents. Of the 455 direct fatalities in the U.S. due to hurricanes from 2013 to 2023 — a figure that excludes deaths from 2017’s Hurricane Maria — less than 15% were caused by wind, National Hurricane Center director Mike Brennan said during a recent public meeting. The rest were caused by storm surges, flooding and rip tides.

The Saffir-Simpson scale is a relic of an earlier age in forecasting, Brennan said.

“Thirty years ago, that’s basically all we could tell you about a hurricane, is how strong it was right now. We couldn’t really tell you much about where it was going to go, or how strong it was going to be, or what the hazards were going to look like,” Brennan said during the meeting, which was organized by the American Meteorological Society. “We can tell people a lot more than that now.”

He confirmed the National Hurricane Center has no plans to introduce a Category 6, primarily because it is already trying “to not emphasize the scale very much,” Brennan said. Other meteorologists said that’s the right call.

“I don’t see the value in it at this time,” said Mark Bourassa, a meteorologist at Florida State University’s Center for Ocean-Atmospheric Prediction Studies. “There are other issues that could be better addressed, like the spatial extent of the storm and storm surge, that would convey more useful information [and] help with emergency management as well as individual people’s decisions.”

Simplistic as they are, Herbert Saffir and Robert Simpson’s categories are the first thing many people think of when they try to grasp the scale of a storm. In that sense, the scale’s persistence over the years helps people understand how much the climate has changed since its introduction.

“What the Saffir-Simpson scale is good for is quantifying, showing, that the most intense storms are becoming more intense because of climate change,” Wehner said. “It’s not like it used to be.”

Science

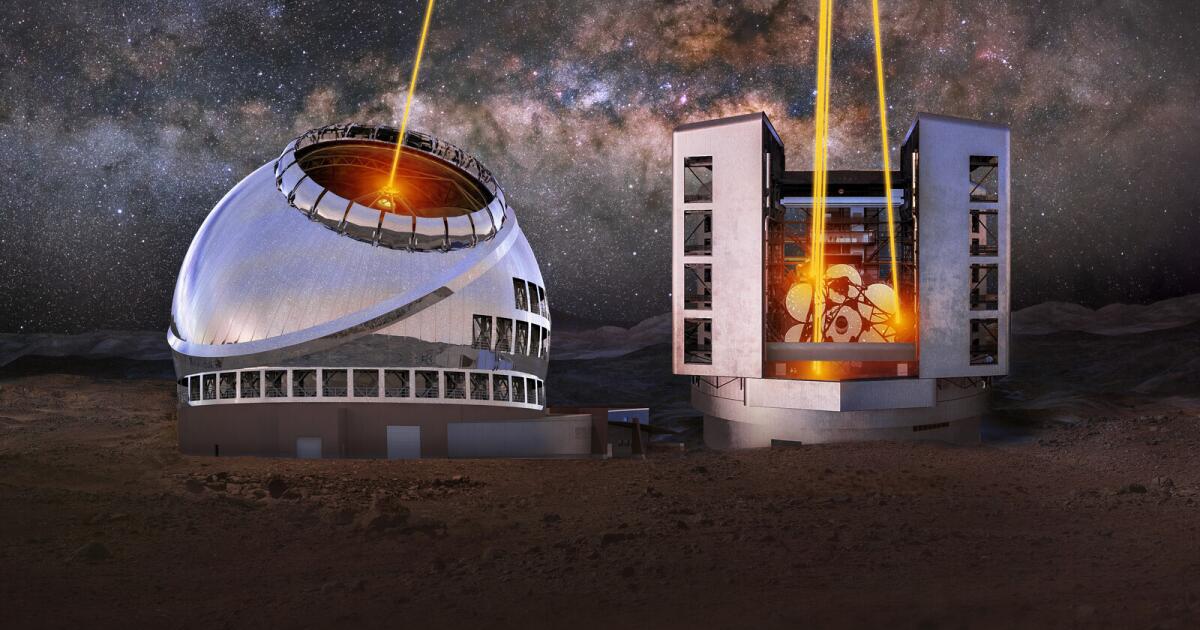

Opinion: America's 'big glass' dominance hangs on the fate of two powerful new telescopes

More than 100 years ago, astronomer George Ellery Hale brought our two Pasadena institutions together to build what was then the largest optical telescope in the world. The Mt. Wilson Observatory changed the conception of humankind’s place in the universe and revealed the mysteries of the heavens to generations of citizens and scientists alike. Ever since then, the United States has been at the forefront of “big glass.”

In fact, our institutions, Carnegie Science and Caltech, still help run some of the largest telescopes for visible-light astronomy ever built.

But that legacy is being threatened as the National Science Foundation, the federal agency that supports basic research in the U.S., considers whether to fund two giant telescope projects. What’s at stake is falling behind in astronomy and cosmology, potentially for half a century, and surrendering the scientific and technological agenda to Europe and China.

In 2021, the National Academy of Sciences released Astro2020. This report, a road map of national priorities, recommended funding the $2.5-billion Giant Magellan Telescope at the peak of Cerro Las Campanas in Chile and the $3.9-billion Thirty Meter Telescope at Mauna Kea in Hawaii. According to those plans, the telescopes would be up and running sometime in the 2030s.

NASA and the Department of Energy backed the plan. Still, the National Science Foundation’s governing board on Feb. 27 said it should limit its contribution to $1.6 billion, enough to move ahead with just one telescope. The NSF intends to present their process for making a final decision in early May, when it will also ask for an update on nongovernmental funding for the two telescopes. The ultimate arbiter is Congress, which sets the agency’s budget.

America has learned the hard way that falling behind in science and technology can be costly. Beginning in the 1970s, the U.S. ceded its powerful manufacturing base, once the nation’s pride, to Asia. Fast forward to 2022, the U.S. government marshaled a genuine effort toward rebuilding and restarting its factories — for advanced manufacturing, clean energy and more — with the Inflation Reduction Act, which is expected to cost more than $1 trillion.

President Biden also signed into law the $280-billion CHIPS and Science Act two years ago to revive domestic research and manufacturing of semiconductors — which the U.S. used to dominate — and narrow the gap with China.

As of 2024, America is the unquestioned leader in astronomy, building powerful telescopes and making significant discoveries. A failure to step up now would cede our dominance in ways that would be difficult to remedy.

The National Science Foundation’s decision will be highly consequential. Europe, which is on the cusp of overtaking the U.S. in astronomy, is building the aptly named Extremely Large Telescope, and the United States hasn’t been invited to partner in the project. Russia aims to create a new space station and link up with China to build an automated nuclear reactor on the moon.

Although we welcome any sizable grant for new telescope projects, it’s crucial to understand that allocating funds sufficient for just one of the two planned telescopes won’t suffice. The Giant Magellan and the Thirty Meter telescopes are designed to work together to create capabilities far greater than the sum of their parts. They are complementary ground stations. The GMT would have an expansive view of the southern hemisphere heavens, and the TMT would do the same for the northern hemisphere.

The goal is “all-sky” observation, a wide-angle view into deep space. Europe’s Extremely Large Telescope won’t have that capability. Besides boosting America’s competitive edge in astronomy, the powerful dual telescopes, with full coverage of both hemispheres, would allow researchers to gain a better understanding of phenomena that come and go quickly, such as colliding black holes and the massive stellar explosions known as supernovas. They would put us on a path to explore Earth-like planets orbiting other suns and address the question: “Are we alone?”

Funding both the GMT and TMT is an investment in basic science research, the kind of fundamental work that typically has led to economic growth and innovation in our uniquely American ecosystem of scientists, investors and entrepreneurs.

Elon Musk’s SpaceX is the most recent example, but the synergy goes back decades. Basic science at the vaunted Bell Labs, in part supported by taxpayer contributions, was responsible for the transistor, the discovery of cosmic microwave background and establishing the basis of modern quantum computing. The internet, in large part, started as a military communications project during the Cold War.

Beyond its economic ripple effect, basic research in space and about the cosmos has played an outsized role in the imagination of Americans. In the 1960s, Dutch-born American astronomer Maarten Schmidt was the first scientist to identify a quasar, a star-like object that emits radio waves, a discovery that supported a new understanding of the creation of the universe: the Big Bang. The first picture of a black hole, seen with the Event Horizon Telescope, was front-page news in 2019.

We understand that competing in astronomy has only gotten more expensive, and there’s a need to concentrate on a limited number of critical projects. But what could get lost in the shuffle are the kind of ambitious projects that have made America the scientific envy of the world, inspiring new generations of researchers and attracting the best minds in math and science to our colleges and universities.

Do we really want to pay that price?

Eric D. Isaacs is the president of Carnegie Science, prime backer of the Giant Magellan Telescope. Thomas F. Rosenbaum is president of Caltech, key developer of the Thirty Meter Telescope.

Science

Mosquito season is upon us. So why are Southern California officials releasing more of them?

Jennifer Castellon shook, tapped and blew on a box to shoo out more than 1,000 mosquitoes in a quiet, upscale Inland Empire neighborhood.

The insects had a job to do, and the pest scientist wanted every last one out.

Aggressive and impactful reporting on climate change, the environment, health and science.

Their task? Find lady mosquitoes and mate.

But these were no ordinary mosquitoes. Technicians had zapped the insects, all males, with radiation in a nearby lab to make them sterile. If they achieve their amorous quest, there will be fewer baby mosquitoes than there would be if nature ran its course. That means fewer mouths to feed — mouths that thirst for human blood.

“I believe, fingers crossed, that we can drop the population size,” said Solomon Birhanie, scientific director for the West Valley Mosquito and Vector Control District, which released the mosquitoes in several San Bernardino County neighborhoods this month.

Sterilized male Aedes mosquitoes are released from a box in Rancho Cucamonga.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

Controlling mosquitoes with mosquitoes

Mosquito control agencies in Southern California are desperate to tamp down an invasive mosquito — called Aedes aegypti — that has exploded in recent years. Itchy, unhappy residents are demanding it. And the mosquitoes known for fierce ankle biting aren’t just putting a damper on outdoor hangouts — they also spread disease.

The low-flying, day-biting mosquitoes can lay eggs in tiny water sources. A bottle cap is fair game. And they might lay a few, say, in a plant tray and others, perhaps, in a drain. Tackling the invaders isn’t easy when it can be hard to even locate all the reproduction spots. So public health agencies increasingly are trying to use the insects’ own biology against them by releasing sterilized males.

The West Valley district, which covers six cities in San Bernardino County, rolled out the first program of this kind in California last year. Now they’re expanding it. Next month, a vector district covering a large swath of Los Angeles County will launch its own pilot, followed by Orange County in the near future. Other districts are considering using the sterile insect technique, as the method is known, or watching early adopters closely.

On the plus side, it’s an approach that doesn’t rely on pesticides, which mosquitoes become resistant to, but it requires significant resources and triggers conspiracy theories.

“People are complaining that they can’t go into their backyard or barbecue in the summer,” Birhanie said at his Ontario lab. “So we needed something to strengthen our Aedes control.” Of particular concern is the Aedes aegypti, which love to bite people — often multiple times in rapid succession.

Releasing sterilized male insects to combat pests is a proven scientific technique, but using it to control invasive mosquitoes is relatively new.

Vector control experts often point to the success of a decades-long effort in California to fight Mediterranean fruit flies by dropping enormous quantities of sterile males from small planes. That program, run by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the California Department of Food and Agriculture, costs about $16 million a year. That’s nearly four times West Valley’s annual budget.

So rather than try to tackle every nook and cranny of the district, encompassing roughly 650,000 residents, West Valley decided to use a more targeted approach. If a problem area reaches a certain threshold — over 50 mosquitoes counted in an overnight trap — it becomes a candidate.

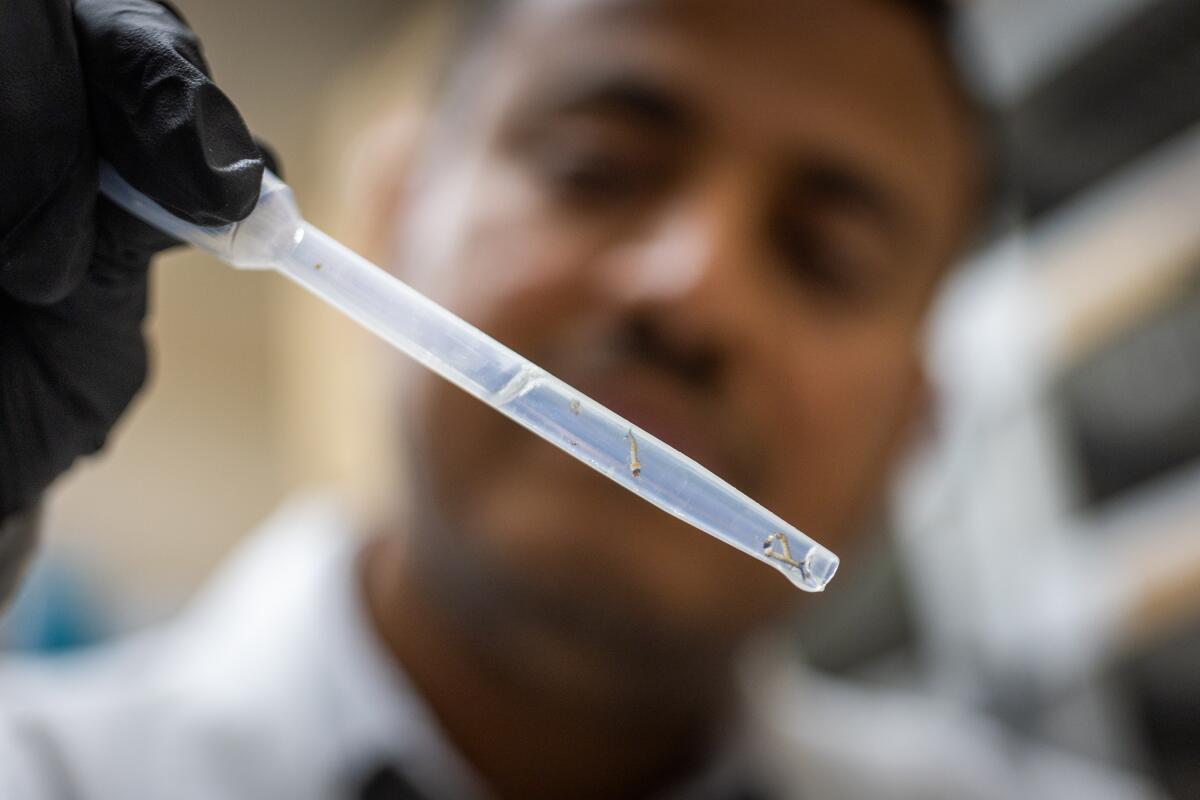

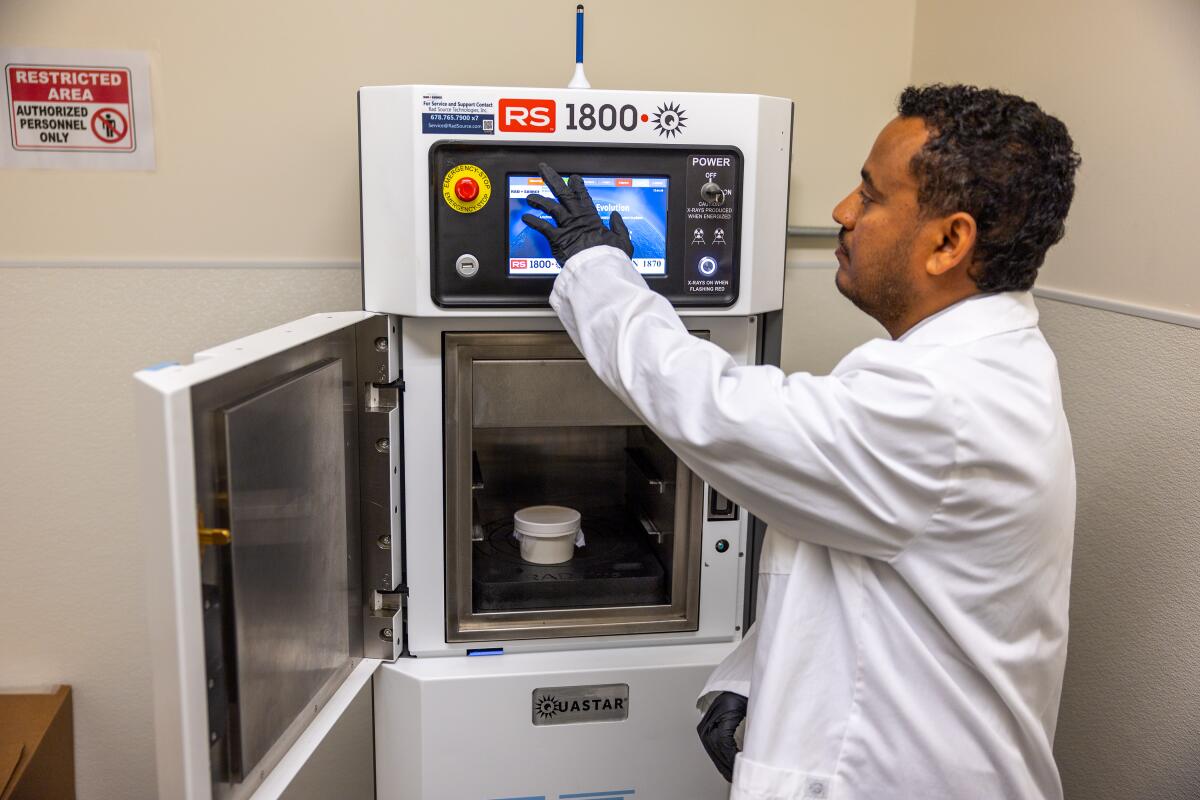

1

2

3

4

5

1. Solomon Birhanie inspects a container of mosquito larvae in the lab at the West Valley Mosquito and Vector Control District in Ontario. 2. Birhanie and his team raise mosquitoes in the lab, separating them by sex, because only the males, which don’t bite humans, will eventually be released. 3. Mosquito eggs in the West Valley lab. 4. The lab can grow about 10,000 mosquitoes at a time. 5. Before the male mosquitoes are released, an X-ray machine sterilizes them. If the zapped males mate with a female, her eggs won’t hatch. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

And it’s still a big lift. About 10,000 mosquitoes are reared at a time at West Valley’s facility, about half of which will be males. The males are separated out, packed into cups and placed into an X-ray machine that looks like a small refrigerator. The sterilizing process isn’t that different from microwaving a frozen dinner. Zap them on a particular setting for four to five minutes and they’re good to go.

Equipment purchased for the program costs roughly $200,000, said Brian Reisinger, spokesperson for the district. He said it was too early to pin down a cost estimate for the program, which is expanding.

Some districts serving more people are going bigger.

The Greater Los Angeles County Vector Control District plans to unleash up to 60,000 mosquitoes a week in two neighborhoods in Sunland-Tujunga from mid-May through November.

With the sterile-insect program, “the biggest hurdle we’re up against really is scalability,” said Susanne Kluh, general manager of the L.A. County district, which is responsible for nearly 6 million residents across 36 cities.

In part to save money, Kluh’s district has partnered with the Orange County Mosquito and Vector Control District. They’re sharing equipment and collaborating on studies, but L.A. County’s releases will move forward first, said Brian Brannon, spokesperson for the O.C. district. Orange County expects to release its “ankle biter fighters,” as Brannon called them, in Mission Viejo this fall or next spring.

So far, the L.A. County district has shelled out about $255,000 for its pilot, while O.C. has spent around $160,000. It’s a relatively small portion of their annual budgets: L.A. at nearly $25 million and O.C. at $17 million. But the area they’re targeting is modest.

Mosquito control experts tout sterilization for being environmentally friendly because it doesn’t involve spraying chemicals, and it may have a longer-lasting effectiveness than pesticides. It can also be done now. Other methods involving genetically modified mosquitoes and ones infected with bacteria are stuck in an approval process that spans federal and state agencies. One technique, involving the bacteria Wolbachia was recently approved by the Environmental Protection Agency and is now heading to the California Department of Pesticide Regulation to review, said Jeremy Wittie, general manager for the Coachella Valley Mosquito and Vector Control District.

“Using pesticides or insecticides, resistance crops up very quickly,” said Nathan Grubaugh, associate professor of epidemiology at the Yale School of Public Health.

Vector control experts hope the fact that the sterilization technique doesn’t involve genetic modification will tamp down conspiracy theories that have cropped up around mosquito releases. One erroneous claim is that a Bill Gates-backed effort to release mosquitoes was tied to malaria cases in Florida and Texas. Reputable outlets debunked the conspiracy theory, pointing out that Gates’ foundation didn’t fund the Florida project and that the type of mosquito released (Aedes) does not transmit malaria.

To get ahead of concerns, districts carrying out the releases say they’ve engaged in extensive outreach and education campaigns. Residents’ desire to rid themselves of a scourge may overcome any anxieties.

“I think if you have the choice of getting eaten alive by ankle biters or having a DayGlo male X-rayed mosquito come by looking for a female to not have babies with, you’d probably go for the latter,” Brannon said. (“DayGlo” is a riff on the fluorescent pigment product of the same name — the sterilized mosquitoes were dusted with bright colors to help identify them.)

Sterilized male mosquitoes buzz around vector ecologist Jennifer Castellon as they are released in Rancho Cucamonga earlier this month.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

Disease at our doorstep

As the climate warms and some regions become wetter, dengue is expanding to areas it’s never been seen before — and surging in areas where it’s established. Florida has seen alarming spikes in the viral infection in recent years, and Brazil and Puerto Rico are currently battling severe outbreaks. While most people infected with dengue have no symptoms, it can cause severe body aches and fever and, in rare cases, death. Its alias, “breakbone fever,” provides a grim glimpse into what it can feel like.

In October of last year, the city of Pasadena announced the Golden State’s first documented locally transmitted case of dengue, describing it as “extremely rare” in a news release. That same month, a second case was confirmed in Long Beach. Local transmission means the patient hadn’t traveled to a region where dengue is common; they may have been bitten by a mosquito carrying the disease in their own neighborhood.

Surging dengue abroad means there’s more opportunity for travelers to bring it home. However, Grubaugh said it doesn’t seem that California is imminently poised for a “Florida-like situation,” where there were nearly 1,000 cases in 2022, including 60 that were locally acquired. Southern California in particular lacks heavy rainfall that mosquitoes like, he said. But some vector experts believe more locally acquired cases are inevitable.

Ale Macias releases sterilized male mosquitoes in Upland this month.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

Set them free

In mid-April, a caravan of staffers from the West Valley district traveled to five mosquito “hot spots” in Chino, Upland and Rancho Cucamonga — where data showed mosquito levels were particularly high — to release their first batches of sterilized male mosquitoes for the year. Peak Aedes season is months away, typically August to October in the district, and Birhanie said that’s the point. The goal is to force down the numbers to prevent an itchy tsunami later.

Males don’t bite, so the releases won’t lead to more inflamed welts. But residents might notice more insects in the air. Sterilized males released by West Valley will outnumber females in the wild by at least 100 to 1 to increase their chances of beating out unaltered males, spokeperson Reisinger said.

“They’re not going to be contributing to the biting pressure; they’re just going to be looking for love,” as Reisinger put it.

Eggs produced by a female after a romp with a sterile male don’t hatch. And female mosquitoes typically mate only once, meaning all her eggs are spoiled, so to speak. Vector experts say the process drives down the population over time.

Interestingly, the hot spots were fairly spread out across the district, indicative of the bloodsuckers’ widespread presence and adaptive nature. A picturesque foothills community in Upland was “especially interesting” because of its relatively high elevation, Birhanie said.

It was once inhabited primarily by another invasive mosquito that prefers colder, mountainous climates. Construction and deforestation in the area has literally paved the way for its humidity- and heat-loving brethren to move in.

Another neighborhood, in Rancho Cucamonga, posed a mystery. For the last two years, mosquito levels were consistently high. Door-to-door inspections, confoundingly, didn’t reveal the source.

“That’s one of the things about invasive Aedes mosquitoes — you can’t find them,” he said.

Next steps

Some vector control experts want to see a regional approach to sterile mosquito releases, similar to the state Medfly program.

Jason Farned, district manager for the San Gabriel Valley Mosquito and Vector Control District, believes a widespread effort “would be much more effective” and thinks that will come in time.

There are no talks underway to make it happen, and it’s not yet clear how it would work. Vector control agencies are set up to serve their local communities.

Fears of a bad mosquito year ahead are bubbling as the weather warms. Rain — which there was plenty of this spring — can quickly transform into real estate for mosquito reproduction.

When the swarms come, mosquito haters can take typical precautions: dump standing water and wear repellent. And they can root for the sterile males to get lucky.

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoIf not Ursula, then who? Seven in the wings for Commission top job

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoMovie Review: The American Society of Magical Negroes

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoGOP senators demand full trial in Mayorkas impeachment

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoFilm Review: Season of Terror (1969) by Koji Wakamatsu

-

World1 week ago

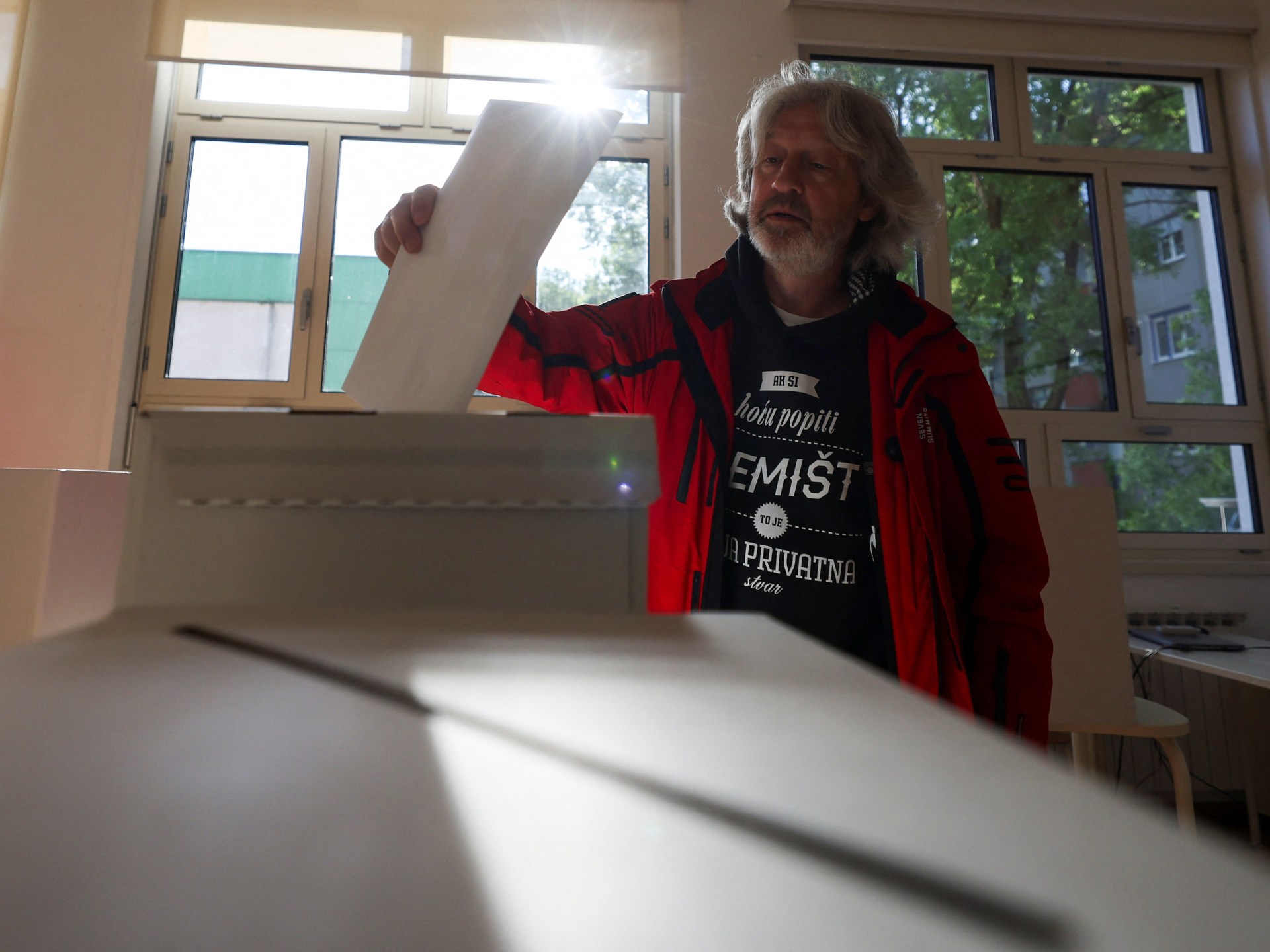

World1 week agoCroatians vote in election pitting the PM against the country’s president

-

World1 week ago

World1 week ago'You are a criminal!' Heckler blasts von der Leyen's stance on Israel

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump trial: Jury selection to resume in New York City for 3rd day in former president's trial

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoAnd the LUX Audience Award goes to… 'The Teachers' Lounge'

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25419931/Screenshot_2024_04_26_at_11.21.35_AM.png)