Science

You're gonna need a bigger number: Scientists consider a Category 6 for mega-hurricane era

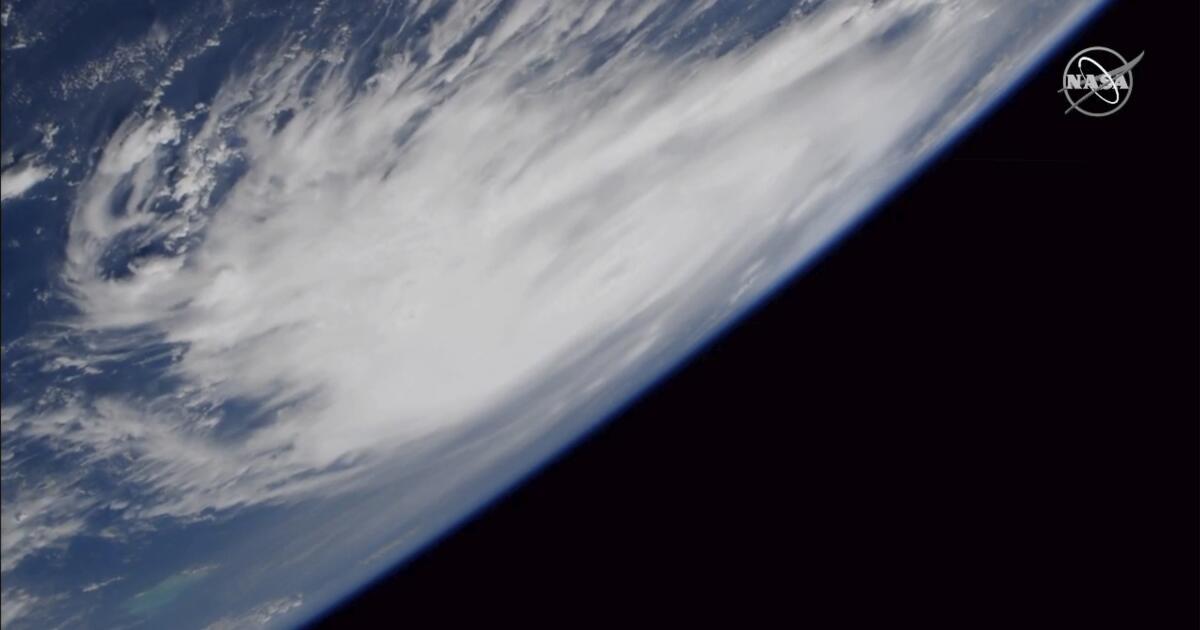

In 1973, the National Hurricane Center introduced the Saffir-Simpson scale, a five-category rating system that classified hurricanes by wind intensity.

At the bottom of the scale was Category 1, for storms with sustained winds of 74 to 95 mph. At the top was Category 5, for disasters with winds of 157 mph or more.

In the half-century since the scale’s debut, land and ocean temperatures have steadily risen as a result of greenhouse gas emissions. Hurricanes have become more intense, with stronger winds and heavier rainfall.

With catastrophic storms regularly blowing past the 157-mph threshold, some scientists argue, the Saffir-Simpson scale no longer adequately conveys the threat the biggest hurricanes present.

Earlier this year, two climate scientists published a paper that compared historical storm activity to a hypothetical version of the Saffir-Simpson scale that included a Category 6, for storms with sustained winds of 192 mph or more.

Of the 197 hurricanes classified as Category 5 from 1980 to 2021, five fit the description of a hypothetical Category 6 hurricane: Typhoon Haiyan in 2013, Hurricane Patricia in 2015, Typhoon Meranti in 2016, Typhoon Goni in 2020 and Typhoon Surigae in 2021.

Patricia, which made landfall near Jalisco, Mexico, in October 2015, is the most powerful tropical cyclone ever recorded in terms of maximum sustained winds. (While the paper looked at global storms, only storms in the Atlantic Ocean and the northern Pacific Ocean east of the International Date Line are officially ranked on the Saffir-Simpson scale. Other parts of the world use different classification systems.)

Though the storm had weakened to a Category 4 by the time it made landfall, its sustained winds over the Pacific Ocean hit 215 mph.

“That’s kind of incomprehensible,” said Michael F. Wehner, a senior scientist at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and co-author of the Category 6 paper. “That’s faster than a racing car in a straightaway. It’s a new and dangerous world.”

In their paper, which was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Wehner and co-author James P. Kossin of the University of Wisconsin–Madison did not explicitly call for the adoption of a Category 6, primarily because the scale is quickly being supplanted by other measurement tools that more accurately gauge the hazard of a specific storm.

“The Saffir-Simpson scale is not all that good for warning the public of the impending danger of a storm,” Wehner said.

The category scale measures only sustained wind speeds, which is just one of the threats a major storm presents. Of the 455 direct fatalities in the U.S. due to hurricanes from 2013 to 2023 — a figure that excludes deaths from 2017’s Hurricane Maria — less than 15% were caused by wind, National Hurricane Center director Mike Brennan said during a recent public meeting. The rest were caused by storm surges, flooding and rip tides.

The Saffir-Simpson scale is a relic of an earlier age in forecasting, Brennan said.

“Thirty years ago, that’s basically all we could tell you about a hurricane, is how strong it was right now. We couldn’t really tell you much about where it was going to go, or how strong it was going to be, or what the hazards were going to look like,” Brennan said during the meeting, which was organized by the American Meteorological Society. “We can tell people a lot more than that now.”

He confirmed the National Hurricane Center has no plans to introduce a Category 6, primarily because it is already trying “to not emphasize the scale very much,” Brennan said. Other meteorologists said that’s the right call.

“I don’t see the value in it at this time,” said Mark Bourassa, a meteorologist at Florida State University’s Center for Ocean-Atmospheric Prediction Studies. “There are other issues that could be better addressed, like the spatial extent of the storm and storm surge, that would convey more useful information [and] help with emergency management as well as individual people’s decisions.”

Simplistic as they are, Herbert Saffir and Robert Simpson’s categories are the first thing many people think of when they try to grasp the scale of a storm. In that sense, the scale’s persistence over the years helps people understand how much the climate has changed since its introduction.

“What the Saffir-Simpson scale is good for is quantifying, showing, that the most intense storms are becoming more intense because of climate change,” Wehner said. “It’s not like it used to be.”

Science

Cyborg jellyfish could help uncover the depths and mysteries of the Pacific Ocean

For years, science fiction has promised a future filled with robots that can swim, crawl and fly like animals. In one research lab at Caltech, what once felt like distant imagination is becoming reality.

At first glance, they look like any other moon jellyfish — soft-bodied, translucent and ghostlike, as their bell-shaped bodies pulse gently through the water. But look closer, and you’ll spot a tangle of wires, a flash of orange plastic, and a sudden intentional movement.

These are no ordinary jellies. These are cyborgs.

At the Dabiri Lab at Caltech, which focuses on the study of fluid dynamics and bio-inspired engineering, researchers are embedding microelectric controllers into jellyfish, creating “biohybrid” devices. The plan: Dispatch these remotely controlled jellyfish robots to collect environmental data at a fraction of the cost of conventional underwater robots — and potentially redefine how we monitor the ocean.

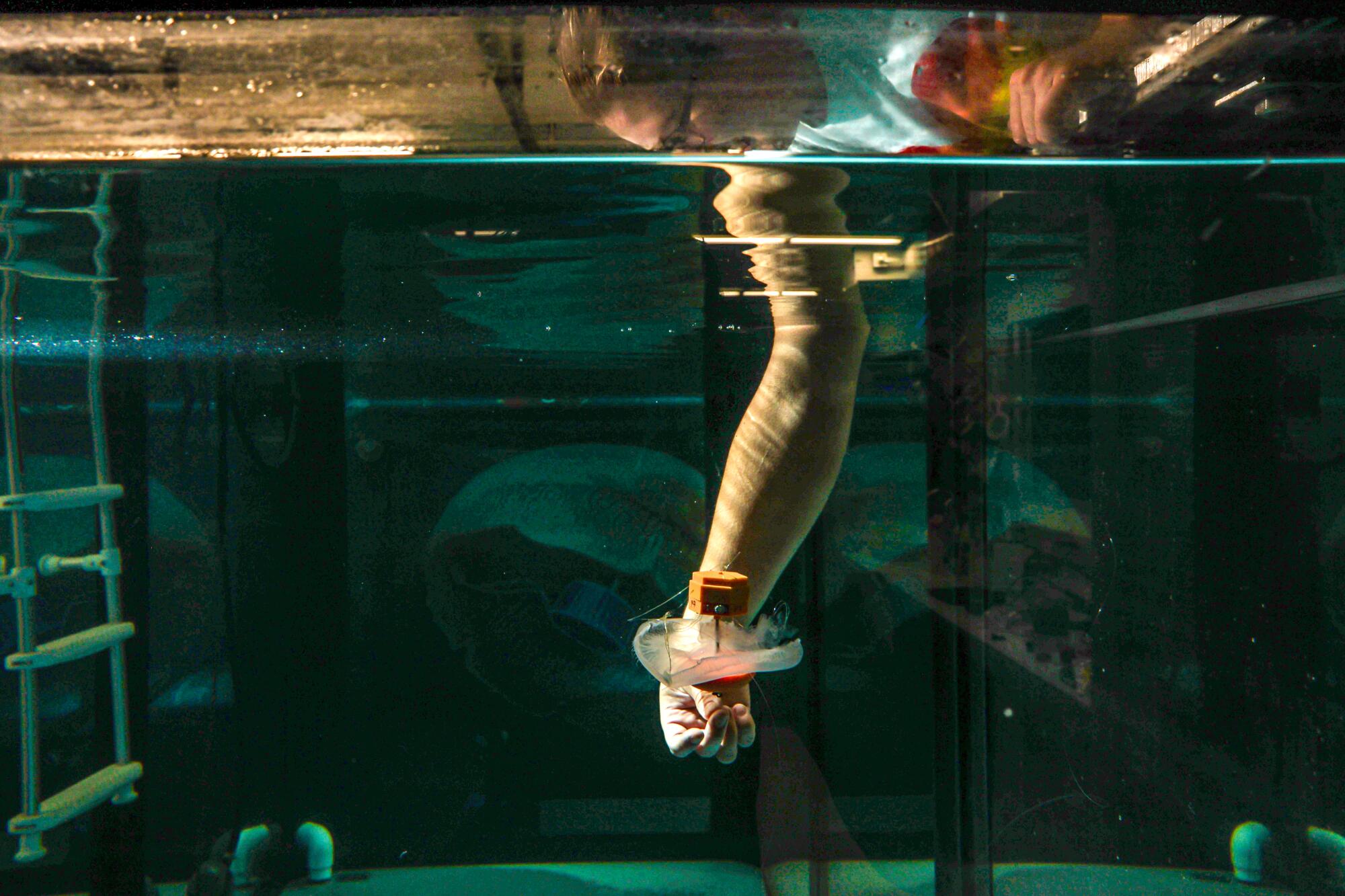

Caltech graduate student, Noa Yoder, a graduate student is one of the members of a team developing cyborg jellyfish, using a device made up of a container filled with sensors and two electrodes that attach to the jellyfish’s muscles.

“It fills the niche between high-tech underwater robots and just attaching sensors to animals, which you have little control over where they go,” said Noa Yoder, a graduate student in the Dabiri Lab. “These devices are very low cost and it would be easy to scale them to a whole swarm of jellyfish, which already exist in nature.”

Jellyfish are perfect for the job in other ways: Unlike most marine animals, jellyfish have no central nervous system and no pain receptors, making them ideal candidates for cybernetic augmentation. They also exhibit remarkable regenerative abilities, capable of regrowing lost body parts and reverting to earlier life stages in response to injury or stress — they can heal in as quickly as 24 hours after the removal of a device.

The project began nearly a decade ago with Nicole Xu, a former graduate student in the Dabiri Lab who is now a professor at the University of Colorado Boulder. Her research has demonstrated that electrodes embedded into jellyfish can reliably trigger muscle contractions, setting the stage for field tests and early demonstrations of the device. Later, another Caltech graduate student, Simon Anuszczyk, showed that adding robotic attachments to jellyfish — sometimes even larger than the jellyfish themselves — did not necessarily impair the animals’ swimming. And in fact, if designed correctly, the attachments can even improve their speed and mobility.

The device allows the scientists to pilot the jellyfish through ocean waters and record measurements of pH, temperature, salinity, etc.

There have been several iterations of the robotic component, but the general concept of each is the same: a central unit which houses the sensors used to collect information, and two electrodes attached via wires. “We attach [the device] and send electric signals to electrodes embedded in the jellyfish,” Yoder explained. “When that signal is sent, the muscle contracts and the jellyfish swims.” By triggering these contractions in a controlled pattern, researchers are able to influence how and when the jellyfish move — allowing them to navigate through the water and collect data in specific locations.

These cyborg devices offer a cheaper (and more sustainable) option for marine research, making it more widely accessible for anyone looking to study the ocean.

The team hopes this project will make ocean research more accessible — not just for elite institutions with multimillion-dollar submersibles, but for smaller labs and conservation groups as well. Because the devices are relatively low-cost and scalable, they could open the door for more frequent, distributed data collection across the globe.

The latest version of the device includes a microcontroller, which sends the signal to stimulate swimming, along with a pressure sensor, a temperature sensor and an SD card to log data. All of which fits inside a watertight 3D-printed structure about the size of a half dollar. A magnet and external ballast keep it neutrally buoyant, allowing the jellyfish to swim freely, and properly oriented.

One limitation of the latest iteration is that the jellyfish can only be controlled to move up and down, as the device is weighted to maintain a fixed vertical orientation, and the system lacks any mechanism to steer horizontally. One of Yoder’s current projects seeks to address this challenge by implementing an internal servo arm, a small motorized lever that shifts the internal weight of the device, enabling directional movement and mid-swim rotations.

Unlike most marine animals, jellyfish have no central nervous system and no pain receptors, making them ideal candidates for cybernetic augmentation.

But perhaps the biggest limitation is the integrity of the device itself. “Jellyfish exist in pretty much every ocean already, at every depth, in every environment,” said Yoder.

To take full advantage of that natural range, however, the technology needs to catch up. While jellyfish can swim under crushing deep-sea pressures of up to 400 bar — approximately the same as having 15 African elephants sit in the palm of your hand — the 3D-printed structures warp at such depths, which can compromise their performance. So, Yoder is working on a deep-sea version using pressurized glass spheres, the same kind used for deep-sea cabling and robotics.

Other current projects include studying the fluid dynamics of the jellyfish itself. “Jellyfish are very efficient swimmers,” Yoder said. “We wanted to see how having these biohybrid attachments affects that.” That could lead to augmentations that make future cyborg jellyfish even more useful for research.

The research team has also begun working with a wider range of jellyfish species, including upside-down Cassiopeia jellies found in the Florida Keys and box jellies native to Kona, Hawaii. The goal is to find native species that can be tapped for regional projects — using local animals minimizes ecological risk.

“This research approaches underwater robotics from a completely different angle,” Yoder said. “I’ve always been interested in biomechanics and robotics, and trying to have robots that imitate wildlife. This project just takes it a step further. Why build a robot that can’t quite capture the natural mechanisms when you can use the animal itself?”

Science

Trump administration sues California over cage-free egg and animal welfare law

The Trump administration has sued California over the state’s voter-approved animal welfare law, which protects hens, pigs and calves from being kept in small cages, claiming the law has driven up egg prices and violates federal farming laws and regulations.

“California has contributed to the historic rise in egg prices by imposing unnecessary red tape on the production of eggs,” wrote lawyers in the lawsuit, which was filed in U.S. District Court in Los Angeles on Wednesday.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom and Atty. Gen. Rob Bonta vowed to defend the state law.

“Pointing fingers won’t change the fact that it is the President’s economic policies that have been destructive. We’ll see him in court,” Bonta said in a statement.

California’s animal-welfare law was approved by voters as Proposition 12 in 2018. The law was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2023.

“In a functioning democracy, policy choices like these usually belong to the people and their elected representatives,” wrote Justice Neil M. Gorsuch, a Trump appointee, in the lead opinion. He said that while many state laws may have economic effects in other states, they are only in violation of the Constitution if they were written with the intent to interfere with interstate commerce.

The Department of Justice contends the California law preempts federal laws, including the Egg Products Inspection Act, and that no state has the right to institute its own standards on the production or “quality, condition, weight, quantity or grade” of eggs that differs from those set by the federal government.

The law has been repeatedly challenged by the National Pork Producers Council and others. Just last month, the Supreme Court declined to accept a petition for certiorari from the Iowa Pork Producers Council.

In the suit filed Wednesday, the Justice Department contends that California’s egg standards “do not advance consumer welfare” and are “not based in specific peer-reviewed published scientific literature or accepted as standards within the scientific community to reduce human food-borne illness … or other human or safety concerns.”

Egg prices soared earlier this year, soon after Trump took office. Most experts pointed to the H5N1 bird flu epidemic as the cause of the spike, as millions of egg-laying chickens across the nation were euthanized to prevent the spread.

Prices have since moderated as the outbreak has diminished. In the last 30 days, there has been only one reported commercial flock infection in Pennsylvania. The birds were not egg layers.

In February, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Secretary Brooke Rollins, penned an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal suggesting the Trump administration would target the law.

California egg producers have in the past opposed changing the law.

Bill Mattos, president of the California Poultry Federation, said in an interview in February that California egg farmers had spent millions of dollars to upgrade and adapt their farms. Reversing the law would put California poultry farmers — and all the other egg producers that sell to California — at a huge economic disadvantage by requiring them to invest millions more dollars to buy cages and re-adapt their facilities for such operations.

Animal welfare advocates say the lawsuit is short-sighted and has the potential to hurt California’s egg-laying industry.

“With this ill-considered legal action, the Administration is dropping a set of stink bombs into the bosom of the egg industry,” said Wayne Pacelle, president of Animal Wellness Action and the Center for a Humane Economy.

He said California egg farmers are still recovering from the bird flu outbreak, and this suit, if successful, would disrupt the still fragile supply chain “and provide an opening for egg farmers from Mexico — which have no animal welfare standards at all — to access the California market.”

Science

Amid state inaction, California chef sues to block sales of foam food containers

Redwood City — Fed up with the state’s refusal to enforce a law banning the sale of polystyrene foam cups, plates and bowls, a San Diego County resident has taken matters into his own hands.

Jeffrey Heavey, a chef and owner of Convivial Catering, a San Diego-area catering service, is suing WinCup, an Atlanta-based foam foodware product manufacturing company, claiming that it continues to sell, distribute and market foam products in California despite a state law that was supposed to ban such sales starting Jan. 1. He is suing on behalf of himself, not his business.

The suit, filed in the San Diego County Superior Court in March, seeks class action status on behalf of all Californians.

Heavey’s attorney, William Sullivan of the Sullivan & Yaeckel Law Group, said his client is seeking an injunction to stop WinCup from selling these banned products in California and to remove the products’ “chasing arrows” recycling label, which Heavey and his attorney describe as false and deceptive advertising.

They are also seeking damages for every California-based customer who paid the company for these products in the last three years, and $5,000 to every senior citizen or “disabled” person who may have purchased the products during this time period.

WinCup didn’t respond to requests for comments, but in a court filing described the allegations as vague, unspecific and without merit, according to the company’s attorney, Nathan Dooley.

Jeffrey Heavey is suing foodware maker WinCup, claiming that it continues to sell, distribute and market foam products in California despite a state law that was supposed to ban such sales starting Jan. 1.

(Luke Johnson / Los Angeles Times)

At issue is a California ban on the environmentally destructive plastic material, which went into effect on Jan. 1, as well as the definition of “recyclable” and the use of such a label on products sold in the state.

Senate Bill 54, signed into law by Gov. Gavin Newsom in 2021, targeted single-use plastic in the state’s waste stream.

The law included a provision that banned the sale and distribution of expanded polystyrene food service ware — such as foam cups, plates and takeout containers — on Jan. 1, unless producers could show they had achieved a 25% recycling rate.

“I’m glad a person in my district has taken this up and is holding these companies accountable,” said Catherine Blakespear (D-Encinitas). “But CalRecycle is the enforcement authority for this legislation, and they should be the ones doing this.”

The intent of the law was to put the financial onus of responsible waste management onto the producers of these products, and away from California’s taxpayers and cities that would otherwise have to dispose of these products or deal with their waste on beaches, in rivers and on roadways.

Expanded polystyrene is a particularly pernicious form of plastic pollution that does not biodegrade, has a tendency to break down into microplastics, leaches toxic chemicals and persists in the environment.

There are no expanded polystyrene recycling plants in California, and recycling rates nationally for the material hover around 1%.

A Mallard duck swims in water with Styrofoam polluting the beach on Lake Washington, Kirkland, Wash.

(Wolfgang Kaehler / LightRocket via Getty Images)

However, despite CalRecycle’s delayed announcement of the ban, companies such as WinCup not only continue to sell these banned products in California, but Heavey and his lawyers allege the products are deceptively labeled as “recyclable.”

In his suit, Heavey includes a March 15 receipt from a Smart & Final store in the San Diego County town of National City, indicating a purchase of “WinCup 16 oz. Foam” cups.

Similar polystyrene foam products could be seen on the shelves this week at a Redwood City Smart & Final, including a 1,000-count box of 12-ounce WinCup foam cups selling for $36.99. Across the aisle, the shelves were packed with bags of Simply Value and First Street (both Smart & Final brands) foam plates and bowls.

There were “chasing arrow” recycling labels on the boxes containing cup lids. The symbol included a No. 6 in the center, indicating the material is polystyrene. There were none on the cardboard boxes containing cups, and it couldn’t be determined if the individual foam products were tagged with recycling labels. They were either obstructed from view inside cardboard boxes or stacked in bags which obscured observation.

Smart & Final, which is owned by Chedraui USA, a subsidiary of Mexico City-based Grupo Comercial Chedraui, didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Heavey’s suit alleges the plastic product manufacturer is “greenwashing” its products by labeling them as recyclable and in so doing, trying to skirt the law.

According to the suit, recycling claims are widely disseminated on products and via other written publications.

The company’s website includes an “Environmental” tab, which includes a page entitled: “Foam versus Paper Disposable Cups: A closer look.”

The page includes a one-sentence argument highlighting the environmental superiority of foam over paper, noting that “foam products have a reputation for environmental harm, but if we examine the scientific research, in many ways Expanded Polystyrene (EPS) foam is greener than paper.”

Heavey’s suit claims that he believed he was purchasing recyclable materials based on the products’ labeling, and he would not have bought the items had they not been advertised as such.

WinCup, which is owned by Atar Capital, a Los Angeles-based global private investment firm sought to have the case moved to the U.S. District Court in San Diego, but a judge there remanded the case back to the San Diego Superior Court or jurisdiction grounds.

Susan Keefe, the Southern California Director of Beyond Plastics, an anti-plastic environmental group based in Bennington, Vt., said that as of June, the agency had not yet enforced the ban, despite news stories and evidence that the product was still being sold in the state.

“It’s really frustrating. CalRecycle’s disregard for enforcement just permits a lack of respect for our laws. It results in these violators who think they can freely pollute in our state with no trepidation that California will exercise its right to penalize them,” she said.

Melanie Turner, a spokesoman for CalRecycle, said in a statement that expanded polystyrene producers “should no longer be selling or distributing expanded polystyrene food service ware to California businesses.”

“CalRecycle has been identifying and notifying businesses that may be impacted by SB 54, including expanded polystyrene requirements, and communicating their responsibilities with mailed notices, emailed announcements, public meetings, and workshops,” she said.

The waste agency “is prioritizing compliance assistance for producers regulated by this law, prior to potential enforcement action,” she said.

Keefe filed a public records request with the agency regarding communications with companies selling the banned material and said she found the agency had not made any attempts to warn or stop the violators from selling banned products.

Blakespear said it’s concerning the law has been in effect for more than six months and CalRecycle has yet to clamp down on violators. Enforcement is critical, she said, for setting the tone as SB 54 is implemented.

According to Senate Bill 54, companies that produce banned products that are then sold in California can be fined up to $50,000 per day, per violation.

According to a report issued by the waste agency last week, approximately 47,000 tons of expanded polystyrene foam was disposed in California landfills last year.

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoVideo: Trump Signs the ‘One Big Beautiful Bill’ Into Law

-

Education1 week ago

Education1 week agoOpinion | The Ugliness of the ‘Big, Beautiful’ Bill, in Charts

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoRussia-Ukraine war: List of key events, day 1,227

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoVideo: Trump Compliments President of Liberia on His ‘Beautiful English’

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoDeath toll from Texas floods rises to 24 as search underway for more than 20 girls unaccounted for | CNN

-

Business7 days ago

Companies keep slashing jobs. How worried should workers be about AI replacing them?

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoTexas Flooding Map: See How the Floodwaters Rose Along the Guadalupe River

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoCyberpunk Edgerunners 2 will be even sadder and bloodier