World

The EU law on platform workers is hanging by a thread. Here's why.

Two years ago, Brussels unveiled ambitious legislation to improve the conditions of those who work for digital platforms such as Uber, Deliveroo and Glovo. Today, the law is scrambling to survive.

The Platform Workers Directive (PWD) was supposed to be a turning point in the so-called Gig Economy as millions of self-employed people who work through platforms across the bloc would be re-classified as employees and benefit from basic rights such as minimum salary, healthcare, accident insurance and paid leave.

But after going through six rounds of negotiations between the European Parliament and member states, the directive was stopped dead in its tracks, right when it was about to reach the finish line.

A meeting in late December, mere hours before Brussels grounded to a halt for the winter break, revealed a larger-than-expected group of countries opposed the draft law that had emerged from the talks.

France, Ireland, Sweden, Finland, Greece and the Baltic countries were among those making it clear they could not support the text on the table, spearheaded by the left-wing government of Spain as holder of the Council’s rotating presidency.

“When you move towards (rules) that would allow massive reclassifications, including self-employed workers who value their self-employed status, we cannot support it,” Olivier Dussopt, then-French minister of labour, said in December.

The co-legislators are expected to honour the deal hashed out in negotiations and push it forward to the final votes so the last-minute resistance, paired with its seize, sent alarm bells ringing.

Another bruising round of negotiations is now all but guaranteed, although no date has yet been selected.

The situation is particularly precarious as the June elections to the European Parliament impose a deadline for concluding interinstitutional talks by mid-February.

A question of presumption

The objections voiced by the no-go coalition all coincide in one critical point: the legal presumption of employment foreseen by the directive. This is the core pillar of the proposed law, without which the PWD would be effectively bereft of its raison d’être.

The legal presumption is the system under which a digital platform would be considered an employer, rather than just an intermediate, and the worker would be considered an employee, rather than a self-employed person.

Under the original proposal by the European Commission, the re-classification would happen if two out of five conditions are met in practice:

- The platform determines the level of remuneration or sets upper limits.

- The platform electronically oversees the performance of workers.

- The platform restricts the ability of workers to choose their working hours, refuse tasks or use subcontractors.

- The platform imposes mandatory rules of appearance, conduct and performance.

- The platform limits the ability to build a client base or to work for a competitor.

According to the Commission’s estimates, about 5.5 million of the 28 million platform workers active across the bloc are currently misclassified and would therefore fall under the legal presumption. Doing so would make them entitled to rights like minimum wage, collective bargaining, work-time limits, health insurance, sick leave, unemployment benefits and retirement pensions – on par with any other regular worker.

The re-classification could be challenged, or rebutted, by either the company or the workers themselves. The burden of proof would fall on the platform to demonstrate the relation of employer-employee does not correspond with reality.

‘Pretty delicate’

From the very start, the directive proved contentious among member states, which are traditionally protective of their labour policies and welfare systems.

Before heading into talks with the Parliament, the 27 countries agreed on a common position that made considerable alterations to the legal presumption, expanding the criteria to seven and adding a vague provision to bypass the system in certain cases.

Meanwhile, MEPs opted instead for a general presumption clause that would apply, in principle, to all platform workers. The criteria to re-classify as employees would only kick in during the rebuttal phase, making it harder for companies to circumvent the system. Lawmakers also strengthened the transparency requirements on algorithms and turned up the heat on penalties for non-compliant firms.

The gap between the Council and the Parliament slowed down the negotiations, known as trilogue, with six rounds needed to reach a deal, a particular high number.

But while MEPs cheered on the breakthrough, a rebellion erupted in the Council.

The resistance stems from the legal presumption of employment, which the trilogue reverted to the original 2/5 criteria, the balance between full-time and part-time workers, the administrative burden placed on private companies and the potential adverse effects on the digital economy as a whole.

“All in all, the issue is that the text doesn’t provide legal clarity and is not in line with the Council’s agreement,” said one diplomat from the group of countries that oppose the deal under condition of anonymity. “Protecting workers, yes, but competitiveness should remain.”

Another diplomat said the position struck in the Council was “pretty delicate” and left minimum space for concessions. “It’s difficult. It’s not an easy file,” the official noted.

From Spain to Belgium

As of today, the trilogue deal decisively falls short of the necessary qualified majority to move forward. Adding an extra twist, Germany, the bloc’s largest country, has so far kept silent, which has been interpreted as the prelude to an abstention. If Berlin sits out the vote, the path to a qualified majority becomes even steeper.

Coincidentally, some of the reluctant countries are home to some of the most prominent digital platforms in Europe: Bolt (Estonia), Wolt (Finland), Free Now and Delivery Hero (Germany). These firms, together with Glovo (Spain), Uber (US) and Deliveroo (UK), have set up industry associations in Brussels and boosted their lobbying spending to defend their corporate interests and influence the draft law.

One of these associations, Move EU, publicly celebrated the December rejection and called the directive “not fit for purpose.” The statement sharply criticised the legal presumption, arguing it would “overwhelm national courts and undo positive reforms.”

By contrast, the European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC) said the proposed law was being “held up for no good reason” and called on the institutions to wrap up the file. “The agreement found in trilogues was far from ideal but finally brought some basic standards to the sector,” the confederation said.

The political hot potato is now in the hands of Belgium, which took over the Council’s presidency on 1 January. Belgium intends to come up with a new common position and head into a seventh round of negotiations with MEPs.

“We’re very determined to reach an agreement, but not at any price. Because, of course, we have to maintain the initial ambition” set by the Commission’s proposal, Pierre-Yves Dermagne, Belgian’s minister for the economy and labour, said last week.

“We know the timing is quite tight. We’re talking a matter of weeks, really.”

But the road ahead is ridden with obstacles. A fresh push in the Council to satisfy the demands of the blocking coalition may trigger the backlash of left-wing governments. France, in particular, is seen as adamantly opposed to the directive.

And even if the Council manages to somehow overcome the odds and overhaul its common position, there is no guarantee that MEPs will be willing to give in and water down the December deal. If the text fails to complete the trilogue phase by mid-February, the cut-off date imposed by the elections, it will be plunged into legislative limbo.

“We are now in a stalemate, with the Belgian Presidency faced with the task of reconciling such opposing positions that the outcome risks being a very weak regulation,” said Agnieszka Piasna, a senior researcher at the European Trade Union Institute (ETUI).

“If the Council doesn’t change its position, we could see a directive that sets the minimum floor so low that conditions for platform workers in some countries could actually worsen, and even obstruct the legal route – which, despite being incredibly costly and cumbersome, has so far been an effective way for workers to defend their rights.”

World

Night Court Renewed for Season 3

ad

World

Colombia cuts diplomatic relations with Israel, but its military relies on Israeli technology

Colombia has become the latest Latin American country to announce that it will break diplomatic relations with Israel over its military campaign in Gaza, but the repercussions for the South American nation could be broader than for other countries because of longstanding bilateral agreements over security matters.

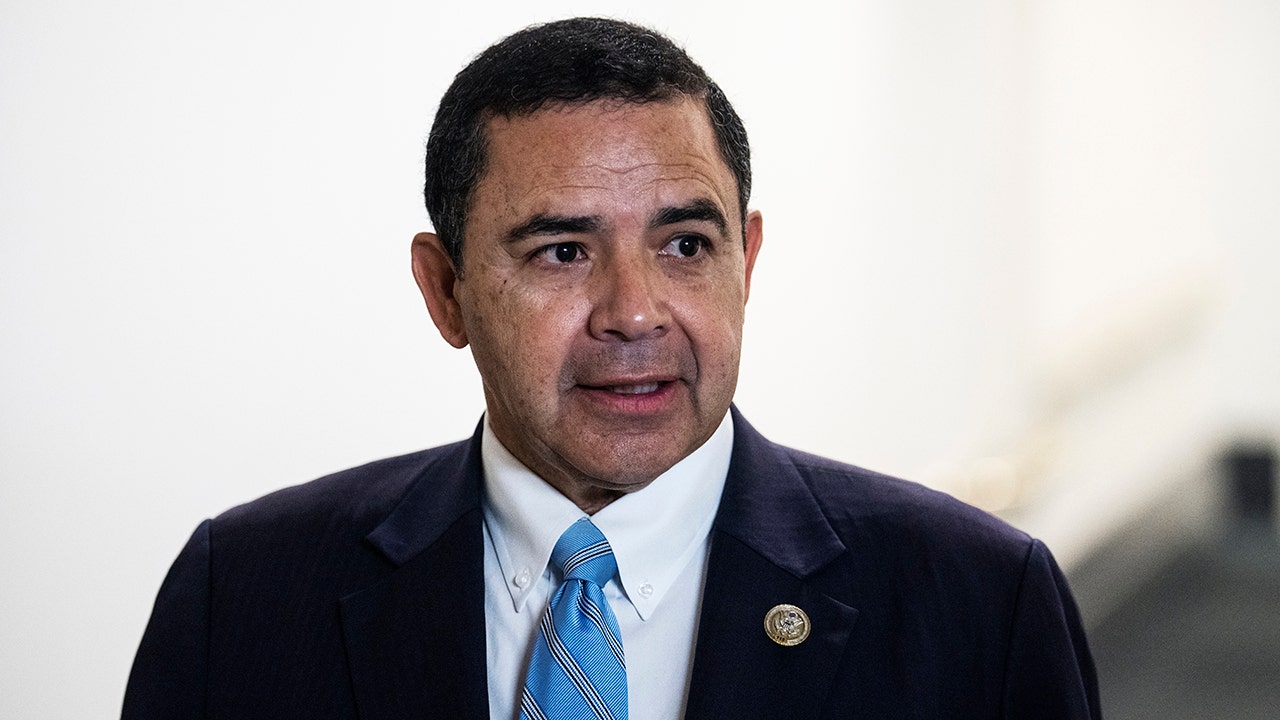

Colombian President Gustavo Petro on Wednesday described Israel’s actions in Gaza as “genocide,” and announced his government would end diplomatic relations with Israel effective Thursday. But he didn’t address how his decision could affect Colombia’s military, which uses Israeli-built warplanes and machine guns to fight drug cartels and rebel groups, and a free trade agreement between both countries that went into effect in 2020.

Also in the region, Bolivia and Belize have severed diplomatic relations with Israel over the Israel-Hamas war.

COLOMBIA’S PRESIDENT SAYS HUNDREDS OF THOUSANDS OF PIECES OF AMMUNITION HAVE GONE MISSING FROM MILITARY BASES

Here’s a look at Colombia’s close Israel ties and fallout:

WHY IS SECURITY COOPERATION BETWEEN COLOMBIA AND ISRAEL IMPORTANT?

Colombia and Israel have signed dozens of agreements on wide-ranging issues, including education and trade, since they established diplomatic relations in 1957. But nothing links them closer than military contracts.

Colombia’s fighter jets are all Israeli-built. The more than 20 Kfir Israeli-made fighter jets were used by its air force in numerous attacks on remote guerrilla camps that debilitated the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia. The attacks helped push the rebel group into peace talks that resulted in its disarmament in 2016.

Colombian President Gustavo Petro speaks at the International Workers’ Day march in Bogota, Colombia, on May 1, 2024. Petro on Wednesday announced his government would end diplomatic relations with Israel. (AP Photo/Fernando Vergara)

But the fleet, purchased in the late 1980s, is aging and requires maintenance, which can only be carried out by an Israeli firm. Manufacturers in France, Sweden and the United States have approached Colombia’s government with replacement options, but the spending priorities of Petro’s administration are elsewhere.

Colombia’s military also uses Galil rifles, which were designed in Israel and for which Colombia acquired the rights to manufacture and sell. Israel also assists the South American country with its cybersecurity needs.

WILL PETRO’S ANNOUNCEMENT AFFECT COLOMBIA’S MILITARY-RELATED CONTRACTS WITH ISRAEL?

It remains unclear.

Colombia’s Foreign Ministry said Thursday in a statement that “all communications related to this announcement will be made through established official channels and will not be public.” The ministry didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment from The Associated Press, while the Israeli Embassy in Bogota declined to address the issue.

However, a day before Petro announced his decision, Colombian Defense Minister Iván Velásquez told lawmakers that no new contracts will be signed with Israel, though existing ones will be fulfilled, including those for maintenance for the Kfir fighters and one for missile systems.

Velásquez said the government has established a “transition” committee that would seek to “diversify” suppliers to avoid depending on Israel. He added that one of the possibilities under consideration is the development of a rifle by the Colombian military industry to replace the Galil.

Security cooperation has been at the center of tensions between the two countries. Israel said in October that it would halt security exports to Colombia after Petro refused to condemn Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack on southern Israel that triggered the war and compared Israel’s actions in Gaza to those of Nazi Germany. In February, Petro announced the suspension of arms purchases from Israel.

For retired Gen. Guillermo León, former commander of the Colombian air force, the country’s military capabilities will be affected if Petro’s administration breaks its contract obligations or even if it complies with them but refuses to sign new ones.

“At the end of the year, maintenance and spare parts run out, and from then on, the fleet would rapidly enter a condition where we would no longer have the means to sustain it,” he told the AP. “This year, three aircraft were withdrawn from service due to compliance with their useful life cycle.”

WHAT IS THE TRADE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE TWO COUNTRIES?

A free trade agreement between Colombia and Israel went into effect in August 2020. Israel now buys 1% of Colombia’s total exports, which include coal, coffee and flowers.

According to Colombia’s Ministry of Commerce, exports to Israel last year totaled $499 million, which represents a drop of 53% from 2022.

Colombia’s imports from Israel include electrical equipment, plastics and fertilizers.

Neither government has explained whether the diplomatic feud will affect the trade agreement.

World

Meloni plans to rally Europe's centre-right in elections pledge

In the run-up to the European elections in June, Euronews takes a closer look at the Brothers of Italy party leader and the country’s prime minister’s speech in Pescara.

The Brothers of Italy’s conference in Pescara was more than a party gathering to launch Meloni’s electoral campaign.

The event marks a key moment in the run-up to the European elections in June, with the Italian prime minister’s address last Sunday providing crucial insight into her conservative leadership in Europe and her EU goals.

At the event, she announced that voters should use just her first name on their ballots. “Call me Giorgia,” she said.

The move is legal, and while many, including her rivals, have criticised her decision, it aligns with her image as a leader with working-class roots who took her first step into politics in Rome’s Garbatella district.

In both her role as Italy’s PM and president of the ECR group, Meloni outlined her vision for Europe.

Notably, she spoke of Brothers of Italy’s increased support over the years since the last European elections in 2019, while commenting on her ambitions to extend what her party has achieved in Italy to the rest of Europe.

“We want to do in Europe what we did in Italy … create a majority that brings together the centre-right forces and send the left into opposition,” Meloni said in Pescara in what has since been highlighted as a key statement.

Alliances based on issues, not ideals

A closer look at Meloni’s speech can help better understand what she has in mind. As ECR Co-Chairman Nicola Procaccini told Euronews, “Meloni refers to a spectrum of positions which sees both the ECR and the EPP as the two main axes when she talks about the creation of a majority that brings together centre-right forces.”

“Then, some delegations from ID in the right-wing camp,” adds Procaccini, “along with others from Renew Europe … will make up the total number that is needed to reach the majority to vote in favour of some measures.”

According to Procaccini, it is crucial to understand that the idea of “majority” within the new 720 seats-strong European Parliament is not fixed and that finding common ground with other political forces remains a possibility.

“Majorities or minorities form themselves based on the single vote. I do believe that the balance within the next European Parliament will shift to the right,” Procaccini said, adding that the EPP and a large part of Renew Europe are already voting alongside ECR, PiS or Viktor Orban’s Fidesz.

“It’s already happening today,” Procaccini continued, “not because there’s a deal in place, but based on the issues we are voting on.”

And as for sending the left into opposition, “it’s about giving the EPP the possibility to break the bond it has built with the socialists and the greens,” Brothers of Italy MP Sara Kelany told Euronews.

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoLarry Webb’s deathbed confession solves 2000 cold case murder of Susan and Natasha Carter, 10, whose remains were found hours after he died

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoHaiti Prime Minister Ariel Henry resigns, transitional council takes power

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoFirst cargo ship passes through new channel since Baltimore bridge collapse

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoSpanish PM Pedro Sanchez suspends public duties to 'reflect'

-

World1 week ago

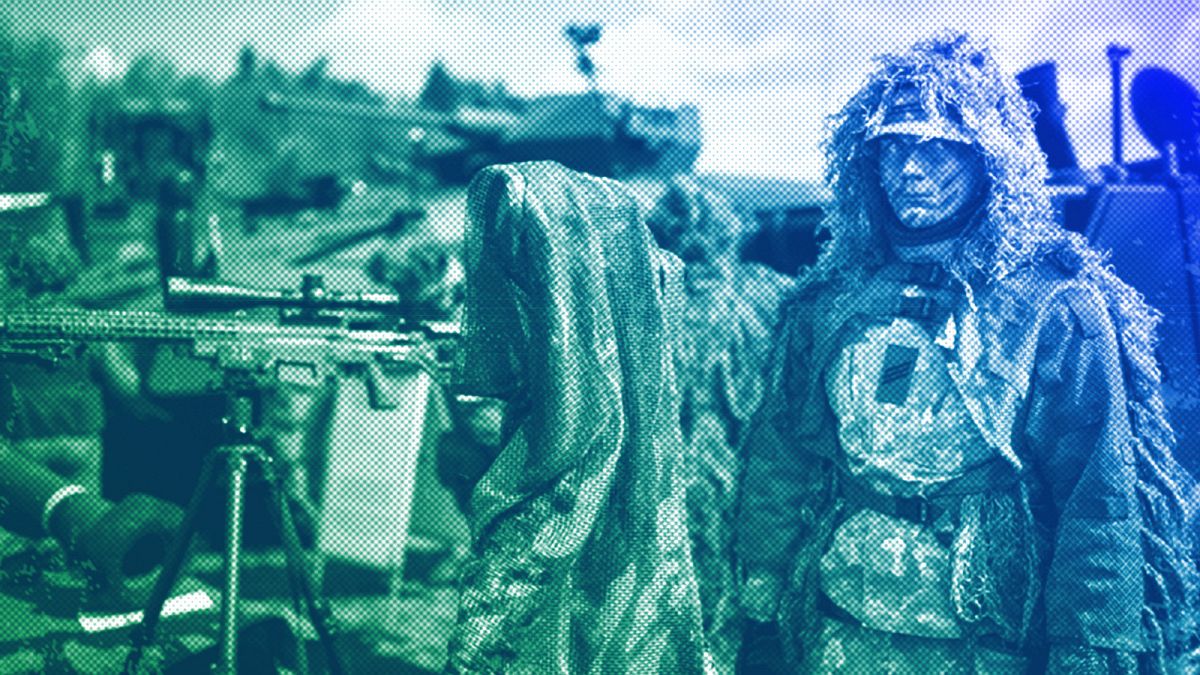

World1 week agoUS secretly sent long-range ATACMS weapons to Ukraine

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoAmerican Airlines passenger alleges discrimination over use of first-class restroom

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoHumane (2024) – Movie Review

-

Education1 week ago

Education1 week agoVideo: Johnson Condemns Pro-Palestinian Protests at Columbia University