World

A brief history of Turkey’s long road to join the European Union

Turkey’s ambition to join the European Union has gone through multiple ups and downs since the application was first submitted in 1987.

Turkey knows a thing or two about being on the doorstep of the European Union.

The country of almost 85 million people holds the unfortunate record of the longest process to join the bloc: 36 years – and counting. No other candidate state in Eastern Europe or the Western Balkans comes even close to matching Turkey’s protracted path to EU membership.

In fact, since Turkey submitted its official application on 14 April 1987 to be part of what was then the European Economic Community (EEC), 16 countries have seen their bids green-lighted, making Ankara’s omission even more glaring.

After a continued succession of ups and downs, promises and threats, it has become apparent that Turkey’s accession is a unique case of policy-making that Brussels has not quite learned how to manage.

From Atatürk to Hallstein

To understand Turkey’s EU ambitions, we must go all the way back to the days of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the revolutionary leader who resisted the country’s partition in the aftermath of World War I and forced the victorious Allies to negotiate favourable terms under the Treaty of Lausanne.

This paved the way for the proclamation of the Republic of Turkey on 29 October 1923 as a one-party parliamentary system with a president, Atatürk himself, as head of state.

Atatürk then launched an intense and rapid series of reforms to build a modern, Westernised country: in the span of a decade, the newly-formed republic saw the abolition of the Caliphate, the introduction of a Latin-script alphabet, a raft of European-inspired laws, drastic changes in dressing codes and the enactment of secularism in the constitution.

The radical transformation paid off. In 1949, Turkey was among the first countries to join the Council of Europe, the Strasbourg-based human rights organisation. In 1952, it became a member of NATO, the transatlantic military alliance created in direct opposition to the Soviet Union.

By then, Ankara had set its sights on the nascent project of European integration in Western Europe. In 1959, the country applied to become an associate member of the European Economic Community (EEC), a request granted four years later.

“Turkey is part of Europe,” declared Walter Hallstein, the president of the EEC Commission, while celebrating the signature of the association agreement in September 1963.

“It is an event without parallel in the history of the influence exerted by European culture and politics. I would even say that we sense in it a certain kinship with the most modern of European developments: the unification of Europe.”

But a first major roadblock was erected in the summer of 1974 when Turkish troops invaded the northern part of Cyprus in response to a coup d’état sponsored by the Greek military junta. The conflict split the island in two, a division that still looms large over Turkey’s European dreams.

A long-awaited declaration

Nevertheless, the association agreement provided Ankara with a solid foundation to gradually move forward.

In 1987, Turkey formally submitted its application to join the EEC, then made up of 12 members, including Greece. At the time, Turkey’s GDP per capita was $1,700 – a far cry from the over $16,000 in both Germany and France.

The huge economic gap, coupled with the collapse of the Soviet Union, the reunification of Germany and persistently poor relations with Cyprus and Greece, slowed down Ankara’s bid.

During this time, Turkey was expected to carry out additional reforms to meet the so-called Copenhagen criteria, the fundamental rules that determine a country’s eligibility to join the EU. The criteria, laid down in 1993, impose high standards on democracy, the rule of law, human rights, the protection of minorities and an open market economy.

In the meantime, Brussels offered Ankara an intermediate step in the form of a customs union for the trade of goods other than agriculture, coal and steel, which became fully operational in early 1996.

It wasn’t until December 1999 when EU leaders, during a European Council in Helsinki, unanimously declared Turkey a candidate country, opening the door for Ankara to join their ranks on an equal footing.

“Turkey is a candidate State destined to join the Union on the basis of the same criteria as applied to the other candidate States,” the leaders wrote in their joint conclusions.

The declaration was not merely rhetorical: it gave Turkey access to millions of EU funds in pre-accession assistance.

The absorption capacity

The 2004 enlargement saw the EU move decisively Eastwards and welcome a total of 10 new members, many of which had been subject to the iron fist of the Soviet Union.

For Ankara, it was an awkward affair: the country had submitted its bid well before any of the newcomers, including Cyprus, and was still waiting for the accession process to kick off.

In 2005, the Council finally adopted the framework for negotiations, a nine-page document peppered with references to the rule of law, the EU’s “absorption capacity,” the importance of “good neighbourly relations” and the possible suspension of talks.

“The shared objective of the negotiations is accession. These negotiations are an open-ended process, the outcome of which cannot be guaranteed beforehand,” the document says.

“If Turkey is not in a position to assume in full all the obligations of membership, it must be ensured that Turkey is fully anchored in the European structures through the strongest possible bond.”

The framework served as the main guidelines for the European Commission, which was tasked with steering the negotiations. The talks are split into 35 chapters, a highly complex undertaking that is meant to perfectly align the candidate with all EU rules.

The chapter on science and research was the first one to be opened in 2006 and was provisionally concluded that very same year. In the decade that followed, Turkey, under the leadership of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, managed to open an additional 15 chapters.

But none were closed.

Total standstill

The 2000s marked a period of impressive economic growth for Turkey: its GDP per capita more than tripled, from $3,100 in 2001 to $10,615 in 2010, while services rapidly expanded thanks to sectors such as transport, tourism and finance, deepening the country’s modernisation.

Still, the evolution was not enough to overcome tensions in the Mediterranean and the growing reticence among EU leaders, some of whom began suggesting a full-time membership could be replaced by a “privileged partnership” – a big no for Ankara.

“Between accession and (special) partnership, which Turkey says it does not accept, there is a path of equilibrium that we can find,” French President Nicolas Sarkozy said in 2011. “The best way of getting out of what risks being a deadlock is to find a compromise.”

In response to cautionary words coming from Paris, Berlin and Vienna, Erdoğan raised the stakes and said he expected accession to be completed by 2023 to coincide with the republic’s 100th anniversary. The migration crisis of 2015-2016 gave Turkey political leverage as the country standing between the bloc and millions of Syrian and Afghan refugees.

But things went sour after the July 2016 coup d’état attempt, a critical episode that led Erdoğan to strengthen his grip on power and consolidate what critics decried as a one-man rule.

In November of that year, Members of the European Parliament approved a resolution blasting the “disproportionate repressive measures” introduced under the state of emergency and calling for a “temporary freeze” on accession talks.

The 2017 referendum to install a unitary presidential system granting the head of state vast executive powers further undermined Ankara’s application and fuelled criticism from EU officials and lawmakers, with some even questioning if Turkey could still be considered an eligible candidate according to the Copenhagen criteria.

The fast deterioration culminated in June 2018 when member states put negotiations on hold.

“The Council notes that Turkey has been moving further away from the European Union,” said the conclusions from a meeting in June 2018. “Turkey’s accession negotiations have therefore effectively come to a standstill and no further chapters can be considered for opening or closing.”

Since then, progress has been almost non-existent.

Freed from the expectation of having to meet EU standards, Erdoğan has ramped up his denunciations against the West, ordered controversial drilling operations in the Eastern Mediterranean and maintained active ties with Vladimir Putin despite Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Ties with Brussels have gone so awry that Turkey, which technically speaking is still a candidate country, is now suspected of helping Russia evade EU sanctions.

The 2022 enlargement report released by the European Commission offered a sombre assessment of where things stand now.

“The Turkish government has not reversed the negative trend in relation to reform, despite its repeated commitment to EU accession,” the report reads. “The EU’s serious concerns on the continued deterioration of democracy, the rule of law, fundamental rights and the independence of the judiciary have not been addressed.”

World

Cubs Win Again in Wrigley View Rooftop Lawsuit

A federal judge this week denied a motion to send the Chicago Cubs’ lawsuit against Wrigley View Rooftop—a company that provides 200 guests with a view of neighboring Wrigley Field in exchange for fees—to arbitration. U.S. District Judge Sharon Johnson Coleman rejected Wrigley View Rooftop’s request that she reconsider her denial in January of the company’s motion to dismiss.

Last year the Cubs sued Wrigley View Rooftop and company owner Aidan Dunican, claiming that Wrigley View Rooftop engages in illegal conduct by selling seats to watch Cubs games, concerts and other events from an adjacent building. The lawsuit includes claims for misappropriation, unjust enrichment, unfair competition and unauthorized use of Cubs’ trademarks.

Wrigley View Rooftop denies wrongdoing and insists the dispute must be resolved out-of-court through arbitration. The problem with that argument, Coleman explained, is that the relevant arbitration clause expired in 2023.

That clause stems from the Cubs and rooftop businesses near Wrigley Field, including Wrigley View Rooftop, settling previous litigation back in 2004. The settlement agreements, which contemplated rooftop businesses sharing revenue with the Cubs and contained arbitration clauses, were set to expire in 2023. Those businesses, except for Wrigley View Rooftop, accepted the Cubs’ offers to extend the settlements beyond 2023.

Last year–after the expiration of the settlement agreement–Wrigley View Rooftop defied the Cubs by selling tickets to games and using Cubs’ trademarks. The company is continuing to sell tickets in the 2025 MLB season and uses the tagline, “the last Wrigley rooftop to be independently owned and operated!”

Wrigley View Rooftop maintains the arbitration language should survive expiration of the settlement agreement. As Wrigley View Rooftop tells it, the dispute is mainly about use of trademarks without permission and whether the Cubs have a right to demand royalties from Wrigley View Rooftop. The company says this dispute concerns a legal right that “accrued or vested” under the settlement agreement, which contemplated royalties in exchange for trademark usage. The Cubs disagree; the team says a plain reading of the settlement agreement makes clear the arbitration language ended when the agreement expired. The idea of contractual rights and restrictions continuing beyond a contract’s expiration doesn’t add up, the team insists.

Coleman agreed with the Cubs, saying she found Wrigley View Rooftop’s argument “unfounded.” After the settlement agreement expired, the judge explained, the Cubs were “not entitled to collect royalties,” and Wrigley View Rooftop was not “entitled to use” Cubs’ trademarks without permission. Along those lines, Coleman noted, the Cubs “do not allege that the expired” settlement provided a right to collect royalties from Wrigley View Rooftop. Instead, the team argues Wrigley View Rooftop “improperly used the trademarks after the expiration of the Settlement Agreement without providing any royalties” to the Cubs.

According to court filings, pretrial discovery of relevant facts must be completed by the parties by June 12. If the case eventually goes to a jury trial, it could resolve a longstanding property law debate over whether rooftop businesses can lawfully sell seats to watch a live performance taking place in an adjacent and famed building, Wrigley Field, built in 1914.

World

A Berlin doctor has been charged with the killings of 15 patients under palliative care

A doctor in Berlin has been charged with murder over the deaths of 15 patients under palliative care, prosecutors said Wednesday. He is also accused of trying to cover up the evidence by starting fires in their homes.

The doctor was part of a nursing service’s end-of-life care team and was initially suspected in the deaths of just four patients. That number has crept higher since last summer, and investigators now say they’ve found evidence linking him to the deaths of 15 people between September 22, 2021, and July 24 last year.

2 PEOPLE ARE KILLED IN A KNIFE ATTACK IN GERMANY; SCHOLZ SAYS THERE MUST BE CONSEQUENCES

The victims’ ages ranged from 25 to 94. Most died in their own homes.

A doctor in Berlin has been charged with murder over the deaths of 15 patients. (REUTERS/Fabrizio Bensch)

He allegedly administered an anesthetic and a muscle relaxer to the patients without their knowledge or consent. The drug cocktail then allegedly paralyzed the respiratory muscles. Respiratory arrest and death followed within minutes, prosecutors said.

The doctor — a 40-year-old man whose name hasn’t been released, in line with German privacy rules — has been in custody since Aug. 6. Prosecutors said Wednesday that he has not yet responded to the case against him.

The charges were filed to the Berlin state court, which will now have to decide whether to bring the case to trial and if so, when.

Murder charges carry a maximum sentence of life in prison. Prosecutors said they aim to ask the court to establish that the suspect bears particularly severe guilt, meaning that he wouldn’t be eligible for release after 15 years as is usually the case in Germany. They also want him to be banned from his profession for life.

World

Trump touts ‘progress’ in Japan trade talks, as uncertainty roils stocks

Wall Street closes sharply lower as US Federal Reserve chair warns tariffs could lead to slower growth, higher inflation.

United States President Donald Trump has touted “big progress” in trade talks with Japan after making an unexpected intervention in the negotiations, as uncertainty caused by his sweeping tariffs continues to roil stock markets.

Trump made his comments on Wednesday after making the surprise decision to sit in on negotiations between his administration and Japanese officials in Washington, DC.

“A Great Honor to have just met with the Japanese Delegation on Trade. Big Progress!” Trump wrote on Truth Social after the talks, which included US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, US Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick and Economic Revitalization Minister Ryosei Akazawa.

Akazawa said after the meeting that Trump wanted to reach a deal before the end of his 90-day pause on his “reciprocal” tariffs, with the Japanese hoping to see the agreement sealed “as soon as possible.”

Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba said the negotiations would not be easy, but the initial rounds of talks had “created a foundation for the next steps”.

Like dozens of other US trade partners, Japan has been hit with a 10 percent baseline tariff in addition to duties of 25 percent on cars, steel and aluminium, which rank among the East Asian country’s top exports.

Japan, a top US security ally and its fourth-largest trade partner, is also facing a targeted 24 percent “reciprocal” tariff under Trump’s “liberation day” trade measures, nearly all of which have been paused until July 9.

“Japan’s industry is so closely integrated in the US economy that everyone is very concerned about the trade talks,” Martin Schulz, chief policy economist at Fujitsu in Tokyo, told Al Jazeera.

“Although there cannot be winners in a trade war, we are also quite optimistic that agreeable results can be achieved. Japan is the largest investor in the US and interested in investing more.”

“If both economies can be kept on a growth track, higher imports from the US become possible,” Schulz added.

The US-Japanese talks came as Wall Street racked up further heavy losses amid continuing uncertainty over Trump’s trade salvoes.

The benchmark S&P 500 closed 2.24 percent lower on Wednesday, while the tech-heavy Nasdaq Composite fell 3.07 percent.

The losses followed a warning by US Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell that Trump’s steep tariffs could leave the US economy grappling with weak growth, rising unemployment and higher inflation all at once.

“We may find ourselves in the challenging scenario in which our dual-mandate goals are in tension,” Powell said in a speech to the Economic Club of Chicago on Wednesday, referring to the US central bank’s twin goals of maximum employment and stable prices.

“If that were to occur, we would consider how far the economy is from each goal, and the potentially different time horizons over which those respective gaps would be anticipated to close.”

US stocks have been on a rollercoaster ride since Trump’s inauguration in January, alternating between sharp dips and big jumps amid his back-and-forth tariff announcements.

Financial markets and businesses have been on tenterhooks waiting for signs that the US president is open to watering down or scrapping many of his tariffs in exchange for concessions from US trading partners.

Trump administration officials have said that more than 75 countries have reached out to begin negotiations on trade.

After the latest losses on Wall Street, the S&P 500 and Nasdaq are down about 10 percent and 15 percent, respectively, since the start of the year.

Asian stock markets got off to a better start on Thursday, with Japan’s benchmark Nikkei 225, South Korea’s KOSPI and Hong Kong’s Hang Seng Index each rising more than 0.5 percent in early trading.

-

News1 week ago

News1 week ago3 Are Killed in Shooting Near Fredericksburg, Va., Authorities Say

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoFilm Review: 'Warfare' is an Immersive and Intense Combat Experience – Awards Radar

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoMen’s NCAA Championship 2025: What to know about Florida, Houston

-

Health1 week ago

Health1 week agoAs RFK Jr. Champions Chronic Disease Prevention, Key Research Is Cut

-

Politics1 week ago

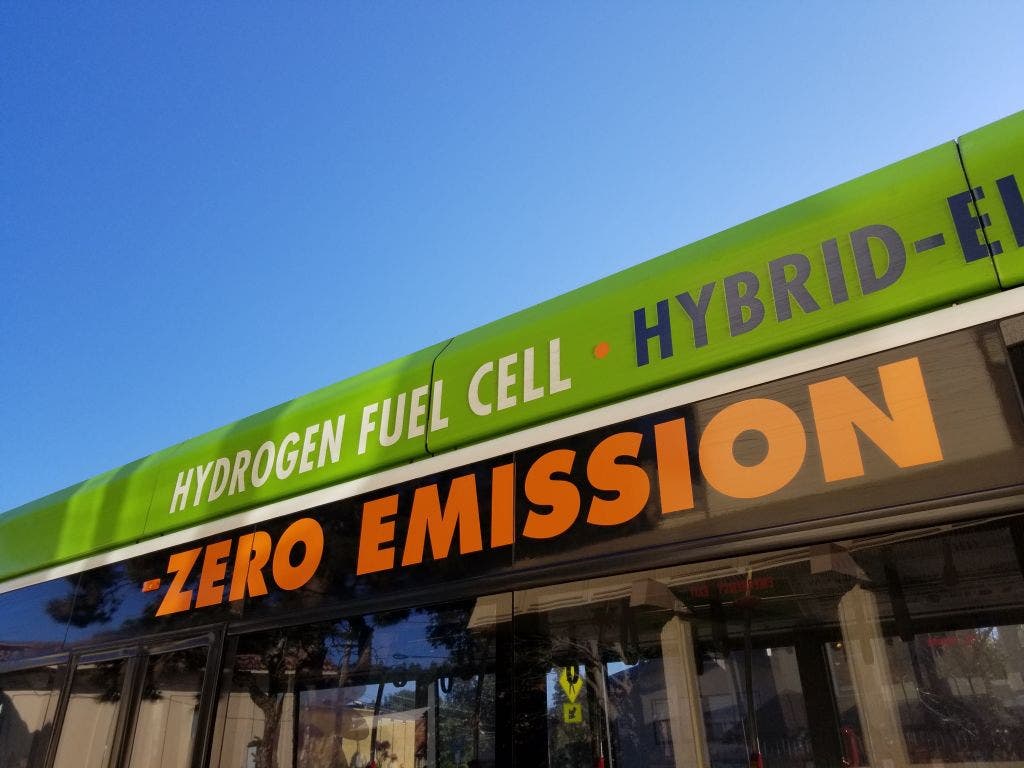

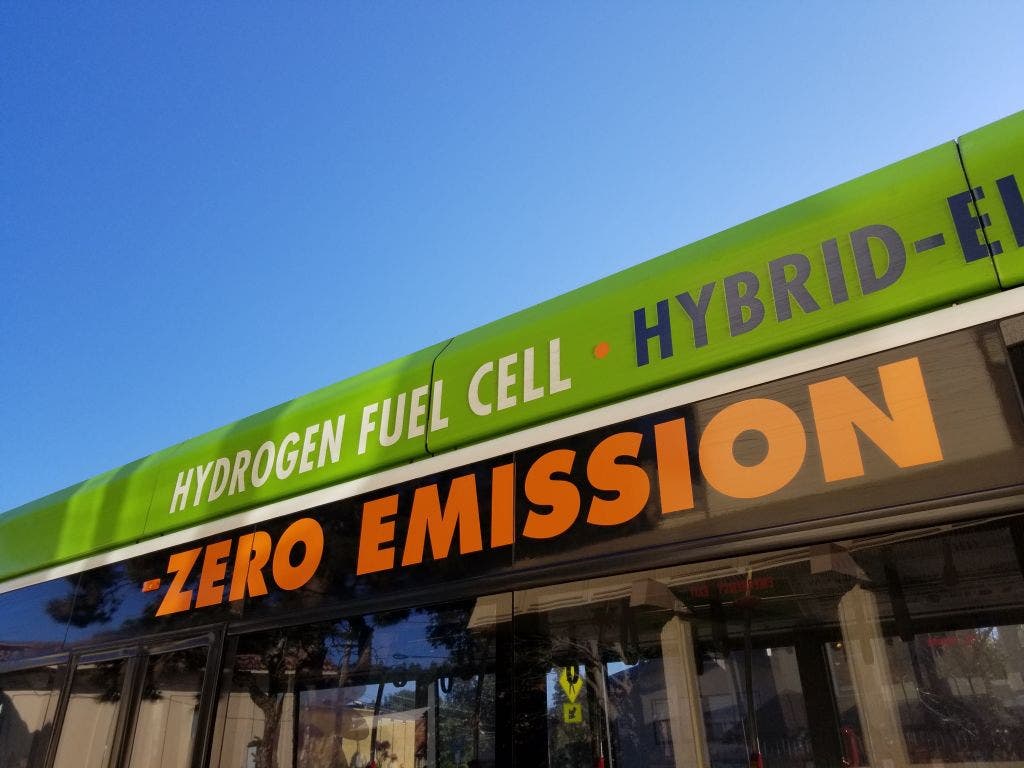

Politics1 week agoH2Go: How experts, industry leaders say US hydrogen is fuel for the future of agriculture, energy, security

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoBoris Johnson Has Run-In With Feisty Ostrich During Texas Trip

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoEPP boss Weber fells 'privileged' to be targeted by billboard campaign

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoMeta got caught gaming AI benchmarks