Lifestyle

'I Just Keep Talking' is a refreshing and wide-ranging essay collection

Nell Irvin Painter — author, scholar, historian, artist, raconteur — rocked my world with her The History of White People and endeared me with her memoir Old in Art School. Painter’s latest book, I Just Keep Talking is an insightful addition to her canon.

Painter’s professional accomplishments are stratospheric: a chair in the American History Department at Princeton, bestselling author of eight books along with others she’s edited, too many other publications to count, and an entirely separate career as a visual artist. She calls her latest book “A Life in Essays,” which I found reductive. Although the first group of essays is entitled “Autobiography,” this volume reaches far beyond Nell Painter’s own story in the best possible way.

Painter’s The History of White People combines scholarship with readability to prove that “whiteness” is a relatively newly created sociological construct. Slavery has been around for millennia, as has war and conquering peoples, but whiteness, with its bizarre, insidious, and pervasive myths about racial superiority, dates from around the 15th century forward. The concept of whiteness is entangled with America’s mendacious justifications for its capture and trade in human beings, and the terrible, lasting consequences of chattel slavery.

Painter has been clear that she stands on the shoulders of others in naming whiteness as a construct. What makes The History of White People indispensable is that it collects the historical antecedents of whiteness in a compelling narrative, and calls out to readers, including myself, the need to unlearn whiteness as a norm, even — and especially — if it is an unconscious norm.

As Painter wound down from a full academic load at Princeton, she obtained undergraduate and graduate degrees in fine art. In Old in Art School, as well as this current volume, she recounts the putdowns and hazing she suffered from fellow art students and her art professors, just as The History of White People was hitting the bestseller lists. Painter acknowledges that book’s commercial success but does not hide her bitterness that it did not win any major prizes.

Painter’s tour through her life and interests makes for a fascinating journey. To introduce her essay collection, Painter writes, “My Blackness isn’t broken… Mine is a Blackness of solidarity, a community, a connectedness….” She grew up in an intellectual family in the Bay Area amidst the burgeoning Black power movement. Her studies took her to Ghana and Paris, before completing her Ph.D. in U.S. history at Harvard.

Painter started making art at an early age. She threads that interest through the essays, wondering what would have happened if her professional life had started with art, instead of as a scholar.

Painter’s captivating mixed media illustrations in I Just Keep Talking speak to injustice. She combines words that blister — “same frustrations for 25 years” (a work from 2022), with blocks of color and figurative representations. I felt drawn in by these visual pieces with their trenchant messages. “This text + art is the way I work, the way I think,” she writes. In Painter’s hands, a picture can be worth a thousand words.

Painter’s essays pose critical questions. She will not accept received wisdom at face value, refuses the status quo, and freely offers her expert opinions. The pieces in this book address such wide topics as the meaning of history and historiography; America’s false, rose-colored-glasses-interpretation of slavery; the appalling absence of Black people from America’s story about itself; how and where feminism fits in; southern American history; the white gaze; and visual culture.

She takes a hard look at Thomas Jefferson’s hypocrisy concerning Black people and slavery, and compares his viewpoint to that of Charles Dickens, who toured the U.S. 15 years after Jefferson died. Audiences cooled to Dickens after he “excoriate[d] Americans for…tolerating the continued existence of enslavement by shrugging their shoulders, saying nothing can be done on account of ‘public opinion.’”

Painter was onto Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas well before Professor Hill delivered her explosive testimony at his confirmation hearing. In a chapter called “Hill, Thomas, and the Use of Racial Stereotype,” Painter delivers a withering takedown of Thomas’ manipulation of gender stereotypes to advantage himself.

Painter dates her essays and provides extensive endnotes, but I wanted more information about which essays had been previously published and which, if any, derived from unpublished journal entries. I wondered particularly about the shorter, less annotated pieces, which I could imagine her writing to develop analyses for longer efforts (though only speculation on my part).

The variety in length and scholarly sophistication is refreshing in this collection. Each entry deals with topics that are sadly as relevant today as they have been throughout America’s history.

Please keep talking Nell Painter, and we’ll keep listening.

Martha Anne Toll is a D.C.-based writer and reviewer. Her debut novel, Three Muses, won the Petrichor Prize for Finely Crafted Fiction and was shortlisted for the Gotham Book Prize. Her second novel, Duet for One, is due out May 2025.

Lifestyle

At Tom Ford, the Power of a Perfect Suit

If you need to find the musician Harrison Patrick Smith in any room that he’s in, just look for the guy in the skinny black suit.

What the pinstripes are to the Yankees, a shrunken, chauffeur driver’s black suit is for Mr. Smith, 28, who performs as the Dare.

And so, on Wednesday evening in Paris, Mr. Smith sat at the Acne Studios fashion show wearing, what else? A reedy, single-breasted suit.

“They’re all slightly different,” he told me. I’ll take his word for it. The Acne suit he wore looked pretty much identical to every suit I’ve ever seen him in. Same slender cut. Same coal shade.

The first one, he said, was cobbled together at his local Goodwill in New York, but he now owns one by Gucci. Maybe, he hoped, Acne would let him keep this one. Mr. Smith said he could use a few more. He’s currently touring Europe, doing his sweaty one-man show.

What I thought was that he made a simple idea work. Years ago, he would have been just another guy in a suit, but men’s fashion has devolved, particularly for his baby-faced generation. Mr. Smith always sort of looks like he’s doing something subversive. Do I even need to point out that he was the only guy in the room wearing a suit?

The Dare though, would have looked less daring at the Tom Ford show an hour later. After all, there is no American label this side of Ralph Lauren for whom the suit has mattered more. Tom Brady, Jay-Z, David Beckham — if a man hovering around middle age made it to a best dressed list, a Tom Ford suit likely graced his shoulders. Mr. Ford has been a leading lobbyist for the meticulous suit since before Mr. Smith was born.

Last year, Haider Ackermann, a Colombian-born designer, was named the Tom Ford creative director. This was his first show for the label, and there was nothing to indicate that any of Mr. Ford’s hard-fought elegance had leaked out of the label.

Certainly, as I entered, sandwiched between what appeared to be two 50-something clients in glimmering tuxedos, I felt underdressed in my khakis and knit cardigan. All the more so when I spotted Mr. Ford in the front row wearing, of course, a double-breasted suit. Suited waiters ringed the room with martinis extended on silver trays — a signal, as I took it, that Mr. Ackermann intended to lead with tailoring. My dress-code inadequacy swelled.

That assumption was wrong. The first men’s looks were oil-slick sportswear: moto jackets with snap-button collars, cropped pebble-grain trousers and animal-skin boots tapering to a witchy pointed toe. I thought not of Mr. Brady, but Buzz Bissinger, the “Friday Night Lights” author whose fondness for uber-lux leather garments nearly sent him to financial ruin.

As Mr. Ackermann said backstage, Mr. Ford has always been “about suiting and red carpet, but there’s a daily life too, and I wanted to embrace that moment.” A very glossy daily life, perhaps.

But Mr. Ackermann did not hold fire on the tailoring for long. Eventually, the suits came. And kept coming.

A charcoal double-breasted suit, worn with a starchy microdot black-and-white shirt and a broad pinstripe suit peaking out beneath a belted trench were pure Patrick Bateman. No accident, as Mr. Ackermann said on a recent podcast that he had been thinking of “American Psycho,” that chronic touchstone for men’s fashion designers.

Backstage, he said he was also envisioning Mr. Ford and the authority that emanates from the founder in his firm-shouldered suits.

As the show flowed, Mr. Ackermann maintained the straight-backed architecture that makes Tom Ford suits a genuine benchmark for men, while redecorating the facade. Colors were bracing, and fits sat off the body just enough, while underpinnings aimed to startle traditionalists.

Though he smirked off the word backstage, there is still an aspirational glamour to these really excellent suits. But they were also charged with a “well, this is new” unconventionally that could draw in a new generation of clients that thumbed past suits previously.

Take the slouchy tweed number worn over a leather shirt, or the almost-tan double-breasted suit with roomy trousers that undulated as the model passed. Slouchy and roomy, it should be said, were not common adjectives during Mr. Ford’s time at the label. (Mr. Ackermann is yet another creative director whose best look may be his own. He took a bow in a capacious double-breasted model with the collar folded over in full self swaddle. Second-skin ease par excellence.)

Or consider the two suits — mint and robin’s egg blue — that were each paired with a fresh-as-driven-snow white shirt and white tie combo. Or the Aquafresh green sportcoat worn with sepia trousers, a lighter cigar-brown shirt and a black tie. (I can hear the ad now: Nine out of 10 leading fashion stylists endorse this look.)

Toward the end, a model in slicked-back hair arrived in a black-and-white dotted suit jacket with slightly contrasting black-on-black dotted trousers. I wish Mr. Smith had been there to see it. It might have convinced him to add a different sort of dark suit to his rotation.

Lifestyle

Ayahuasca-lite? Why cacao ceremonies are showing up all over L.A.

Walking barefoot across the cool tile floor, her silver face gems twinkling in the sunlight, sound bath practitioner and energy healer Maya Andreeva distributed paper cups filled with brown liquid to the 20 mostly youngish adults seated on yoga mats and blankets on the ground.

They had gathered this Saturday morning on Abbot Kinney Boulevard in the courtyard behind the Japanese skincare store Albion Garden to attend Echoes of the Heart, a two-hour cacao, breathwork and sound bath workshop that promised to guide participants toward “deep self-exploration, energetic healing and profound relaxation.”

“Just allow yourself to feel the intention within you,” said Greta Ruljevaite, founder of the wellness brand Xpansion who co-led the workshop with Andreeva. “Speak it into the cacao, your intention, your wisdom, what you choose to let go of. Anything and everything: Speak it into the cacao.”

Maya Andreeva and Greta Ruljevaite, co-leaders of the Echoes of the Heart workshop, put their intentions into cups of cacao.

(Jean Marc Bertolet)

Around the room, participants gazed reverently into their paper cups, some of them mouthing words silently.

“Now bring it up to your heartspace, connecting to your heart,” she continued, as ambient music droned in the background. “Bring it down to the earth for grounding, and then back to your heartspace. … One more inhale together … and drink your cacao.”

With great gravity, they drank.

Over the next two hours the group was first led by Ruljevaite through a breathwork series, and then a sound healing session facilitated by Andreeva. The cacao part of the workshop may have been minimal, but afterward, attendee Saim Alam said the warm, slightly bitter beverage deepened his experience of the event.

“I was genuinely in such a state of bliss the whole time,” he said.

Cacao, the main ingredient in chocolate, has been showing up at an increasing number of wellness events in the L.A. area in recent years. In March alone, Angelenos can attend a Women’s Circle and Cacao Ceremony in Hollywood, a Women’s Day Goddess Circle and Cacao Ceremony at the Grove, a New Moon Cacao Renewal Ceremony at Yoga NoHo Center and the Somos Cacao Ceremony at an undisclosed location in Woodland Hills.

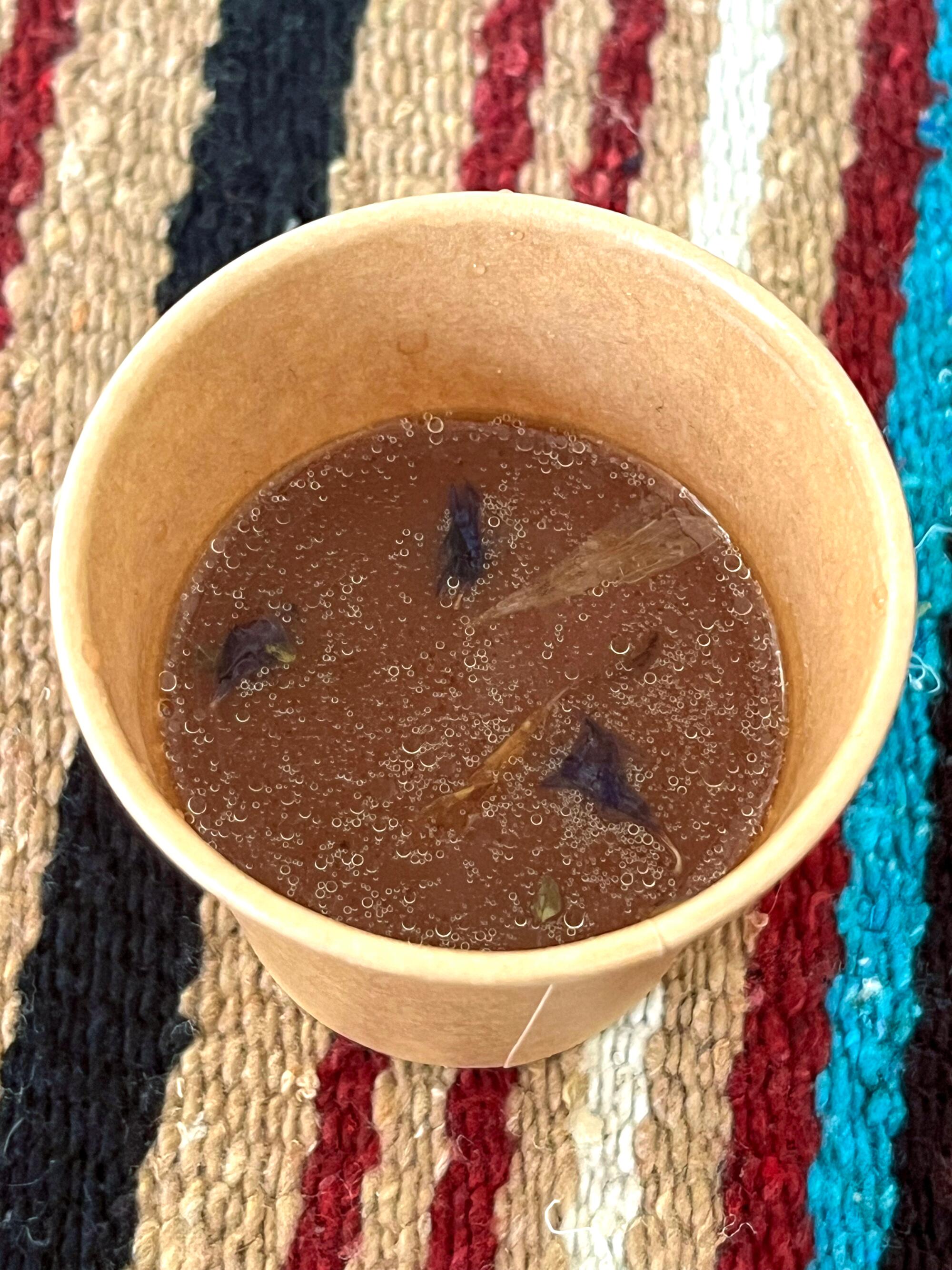

Small edible flowers float on the surface of a cup of cacao at a recent cacao, breathwork and sound healing workshop in Venice.

(Deborah Netburn / Los Angeles Times)

If you want to make the drink yourself, Holy Cacao sells Ecuadorean cacao at farmers markets in Hollywood, Mar Vista, Malibu and Marina del Rey. Local farmers market vendor Arcana Apothecary sells a $60, one-pound block of cacao that is made entirely by women in Guatemala, and pure organic cacao powder is available at Erewhon.

“People hosting cacao experiences continues to grow,” said Nick Meador, who sells ceremonial-grade cacao (an unofficial designation that suggests minimal processing) online through Soul Lift Cacao, the company he founded in 2018. “People want something that gives them a sense of embodied spirituality and cacao is so gentle, you can’t even say there are side effects.”

Practitioners claim that consuming cacao opens the heart, helping drinkers feel more compassionate, blissful, energized and loving. And because it does not have psychedelic properties like other substances labeled “plant medicines,” it is a safe and easy way to experiment with consciousness-altering natural compounds. Consider it ayahuasca lite.

“I was genuinely in such a state of bliss the whole time.”

— Saim Alam, cacao ceremony attendee

“It’s not like any drug I’ve ever taken,” said Kat Ho, who started leading cacao ceremonies in 2021 after being introduced to the drink during the pandemic by an influencer on YouTube. “It’s so mild. Your mind feels a little more loose and you feel a little more clear in the things you want to do.”

When folklorist Taylor Burby was researching cacao ceremonies for her recent graduate thesis, she found that more than 89% of the 118 participants she interviewed said they like to consume cacao because it is a legal, more accessible plant medicine.

Attendees of a cacao, breathwork and sound healing workshop hold cups of cacao at their heart center.

(Jean Marc Bertolet)

“If you take mushrooms you don’t know what’s going to happen,” Burby said. “With cacao you might feel yourself getting warmer or giddy or peaceful, but you have more control over your experience.”

The physical effects of cacao have not been studied as much as coffee, but research suggests that chemical compounds present in cacao can affect mood by increasing both alertness and cognition, and also improve cardiovascular health by lowering blood pressure. And because cacao has much less caffeine than coffee, fans say it gives them an energetic boost without making them jumpy.

“I can feel my shoulders drop, my chest opens,” Andreeva said. “I have felt the energy running through my body like little tingles in spaces where I don’t usually feel that.”

Making ceremonial cacao is a multistep process that traditionally begins with fermenting the seeds of the cacao fruit in their own pulp, drying them in the sun, roasting them over an open fire and then grinding them until they form a paste, which gets poured into a mold to harden.

To prepare the cacao for the Echoes of the Heart workshop, Ruljevaite used a ball of cacao that she had purchased on a recent trip to Guatemala. The night before she meditated over the dark brown sphere, filling it with intentions, and then shaved it into small pieces; mixed it with warm water, oat milk, a little manuka honey and vanilla; and then frothed it. She brought it to the event in an electric Crock-Pot. Just before serving, she and Andreeva whistled over it for a few moments, infusing it with “light language” to give it more potency. Then they ladled the liquid into small cups.

In South and Central America cacao is often served mixed just with water, but without any sweeteners it’s very bitter.

“Our Western tastebuds are not really ready for the traditional experience of cacao,” Andreeva said. “Anywhere I’ve gone in L.A. to drink cacao, it’s never just been raw.”

Archaeological evidence suggests that cacao has been cultivated in Mesoamerica for at least 5,000 years. It was served at betrothals and other celebrations and was a favorite drink of Maya and Aztec nobility, especially in places where it had to be imported, said Rosemary Joyce, a recently retired professor of anthropology at UC Berkeley and an expert on the history of cacao. Texts from the 16th century show the plant was used by Indigenous people medicinally to treat an array of ailments and cacao was consumed in rituals and ceremonies, mostly to repair relationships between the human and spirit worlds, she said.

Joyce has been offered traditional cacao while doing fieldwork in Honduras.

Maya Andreeva, a sound bath practitioner and yoga teacher, ladles cacao from a pot into a paper cup.

(Deborah Netburn / Los Angeles Times)

“It tastes like medicine — there’s no way around it,” she said.

Despite its storied history, her research suggests that ancient uses of cacao in Mesoamerica bear little resemblance to the rituals many Westerners are crafting today.

“It’s a tricky area,” she said. “The ceremonies they did required cacao, but the purpose of the ceremony was not to commune with the spirit of cacao or have it come down and take over your body. That’s a very Western notion.”

Most modern-day cacao ceremonies trace their origin to Keith Wilson, a geologist, adventurer and founder of Keith’s Cacao, who became known as the “Chocolate Shaman.” Wilson, who died last year at his home in Guatemala, claims he was contacted by the cacao spirit in 2003 and given the mission of reintroducing ceremonial cacao to a world that had mostly forgotten about it. He began serving cacao to visitors on his porch, and friends started calling them “cacao ceremonies.” Over time, the area around Lake Atitlán where he settled became known for its cacao ceremonies. Visitors brought the practice back to their home countries.

Meador prefers to label his cacao events “cacao experiences” or “modern cacao ceremonies” to make it clear they are not derived from ancient Indigenous rituals.

“I don’t want to be like a policeman,” he said, “but I teach people to be careful with the words we choose. There are many voices in the conversation and there are people in the U.S. who don’t really actually know that much about it.”

Today in L.A., cacao ceremonies are often paired with other healing modalities such as breathwork, yoga, meditation and dance. Some facilitators will evoke the spirit of cacao, who is supposed to be loving, nurturing and even a bit promiscuous. Burby, the folklorist, once heard it described as “the grandmother that still has sex, rather than the grandma who is over and done and retired.” A facilitator might remind attendees that cacao is a heart opener, that after drinking it one might feel warm, clear and more alert. But after that, anything goes.

“There are just as many ways to practice as people practicing,” Burby said.

Back at Echoes of the Heart, Andreeva and Ruljevaite make it clear they are far from cacao experts. But they had both had positive experiences with the drink and wanted to share it with those who attended their workshop.

“I see it as this beautiful welcoming bridge back to yourself,” Ruljevaite said. “And with a lot of prayers and intention infused in it, and the power and reverence of the community, it heightens and amplifies its benefits.”

Lifestyle

Chemena Kamali of Chloé: The Queen of the Blouse

On the second floor of a 19th-century villa near the Bois de Boulogne, overlooking a garden housing a child’s trampoline and various plastic scooters, there is a room filled with blouses. Hundreds of blouses.

Lace blouses from the Victorian era and big-shouldered blouses from the 1980s. Blouses in paisley and leopard print. Blouses with familiar pedigrees — Ungaro, Yves Saint Laurent, Giorgio di Sant’ Angelo — and blouses with no pedigree at all. A rainbow of blouses arranged according to color on six clothing racks.

Welcome to the mind — or, rather, the home office — of Chemena Kamali, the creative director of Chloé.

If you want to understand how, in only two seasons, she transformed Chloé from an earnest but increasingly minor women’s wear house into one of fashion’s hottest labels, not to mention the uniform of cool girls like Suki Waterhouse and Sienna Miller (and, during her run for president, Kamala Harris), you have to understand Ms. Kamali’s obsession with the blouse.

She has been collecting them for 25 years and has more than 1,500 blouses: at her parents’ home in Germany, in storage in France, almost 500 in her house alone. For her, the blouse — that relatively unappreciated top, redolent of school uniforms, Edwardian nannies and 1970s career girls that lost its primacy of place in the woman’s wardrobe to the T-shirt decades ago — is actually the Platonic ideal of a garment.

“The evolution of the blouse is the evolution of femininity in a way, and the evolution of fashion,” Ms. Kamali said recently, tucked into one of the two giant leather chairs in her office. Aside from the blouses, a big modular desk from the 1980s and some pottery and family tchotchkes are the only objects in the room. She and her husband, Konstantin Wehrum, and their two sons, ages 3 and 5, moved into the house when she got the job at Chloé last year — they had been on their way to California — and she has not had a lot of time to unpack.

“Historically, the blouse was a man’s undergarment,” she said. When she talks about something she loves, you can hear her working through her ideas in real time: “Then, in Victorian times, the blouse became feminized. Postwar, it got more tailored. In the 1970s, again, more fluid, and in the ’80s, more powerful. It can be formal and strict or playful and romantic. It reflects personalities. It reflects all of the things that make us who we are as women.”

That’s a lot of meaning to load onto a garment, but to Ms. Kamali, the blouse is not just a bit of fabric with buttons.

The Shirt on Her Back

No one wears a blouse better than Ms. Kamali, not even converts like Karlie Kloss and Liya Kebede, who have begun to line the Chloé front rows in her lacy tops and wooden platforms. Ms. Kamali’s typical uniform starts with a Chloé blouse of her own design or one from her collection, often in an aged ivory with a touch of embroidery to lend it a vaguely bohemian air.

“A blouse is so much easier than a dress,” she said.

She pairs them with high-waist Chloé jeans, shredded at the hem, white Chloé high-top sneakers and a tangle of necklaces, some new, some sourced at the same vintage markets where she finds her blouses. With waist-length brown hair parted in the center and framing a face that seems makeup free, it creates a vibe that is both Venice Beach hippie — even though Ms. Kamali grew up mostly in Dortmund, Germany — and efficient. If Stevie Nicks had a day job at a venture capital fund, she might look like this.

“She’s aspirational,” said the actress Rashida Jones, who met Ms. Kamali a year ago. “But it doesn’t feel unattainable. It feels grounded.”

Kaia Gerber, who has modeled for Ms. Kamali and wears her clothes off the runway, put it this way: “Chemena herself is a testament to holding your power without having to adhere to the judgments society makes about women based on the way they dress.”

Ms. Kamali, 43, started collecting blouses in 2003, which was around the time she got her first job at Chloé. She knew she wanted to be a designer when she was a child, and in Germany, she said, that meant being like Karl Lagerfeld, the most famous German designer, who was then at Chloé. She went to the University of Applied Sciences in Trier, Germany, and talked her way into Chloé as an intern during the Phoebe Philo era.

“The first designer piece I ever bought, actually, was at the company’s employee sale for 50 euros,” she said, pointing to a white T-shirt with a “necklace” of silver teardrops woven into the front. “That’s when my vintage obsession started, because I remember members of the team coming back from trips with big duffel bags and unpacking treasures they’d found. I realized how certain source pieces can trigger a creative process that can flow into the concept of a collection.”

She got a degree from Central Saint Martins, worked at Alberta Ferretti; Chloé again, under Clare Waight Keller; and then Saint Laurent before returning to Chloé in the top job. But wherever she went, Ms. Kamali kept buying blouses. She does not buy, as many collectors do, for historic or material value but rather according to details that catch her eye — “the volume or the construction of the sleeve or yoke.”

As a result, her pieces are not forbiddingly expensive. They range from “super cheap to maybe $700,” she said, though the average is about $300. She sources them from eBay, vintage fairs like A Current Affair in Los Angeles and what has turned into an extended network of vintage dealers.

“You go to a store, you go to a market and you meet this person who says, ‘OK, you want more of this, I have some stuff in my basement,’” she said. “Then, connecting to this community, this group of obsessive people all about the rare find, becomes an addiction.” It also made her perfect for Chloé.

All Blouses All the Time

The blouse is such an important part of the Chloé aesthetic that when the Jewish Museum in New York held the first major retrospective devoted to Chloé in 2023, it dedicated an entire room to the blouse. As a garment, it encapsulates the easy-breezy-feminine tone set by the founder, Gaby Aghion, in 1952, and was replicated to varying extents by the designers who came after, including Mr. Lagerfeld, Stella McCartney, Ms. Keller and Gabriela Hearst.

But while they all made blouses, none made them as central to their aesthetic as Ms. Kamali had. It is the way “she connects to the fundamental values of the house,” said Philippe Fortunato, the chief executive of the fashion and accessories maisons at Richemont, the Swiss conglomerate that owns Chloe.

Indeed, Ms. Kamali’s first collection for Chloé was built around a blouse. Specifically, a piece Karl Lagerfeld designed for Chloé with a black capelet of sorts built into the top. The blouse, she said, got her “thinking about how the cape is an iconic piece in Chloé’s history.”

Just as the lace in a Victorian blouse had inspired the lacy tiers of the last collection, which were visible not just in actual blouses, but also in playsuits with the affect of blouses and dresses that looked like longer versions of the blouses.

And just as, for her third collection, to be unveiled March 6, Ms. Kamali was thinking about something Karl Lagerfeld once said about “the basic idea being the simplest of all: a blouse and a skirt.”

“That kind of triggered in me the idea of really looking at the blouse not as a component of a look, but as the main component,” she said. That in turn led her to the idea of the blouse as a container of historical fragments: a dolman sleeve, say, or an exaggerated collar or shoulder. All of which made their way into the collection.

“It’s not about copying,” she said. “It’s about using the blouse as a way to root things in the past or in tradition.” And signal that it has a place in the future.

And as Lauren Santo Domingo, a founder of Moda Operandi, reports, it’s working. Chloé is “one of our fastest sellout designers,” Ms. Santo Domingo said, noting that sales of Chloé tops had grown 138 percent since Ms. Kamali’s first collections appeared.

For the photographer David Sims, who shoots the Chloé campaigns, Ms. Kamali has essentially created “the representation of a new French kind of woman, with a play around nudity and embroidery that suggests ownership over a sexual energy and power that feels like an answer to so many of the questions that have sprung up recently.” Questions about gender and stereotype; questions about the male gaze. Doing that through the prism of a garment that was essentially relegated to the dustbin of fashion and old rock stars is, he said, kind of “radical.”

But that tension is actually the point of Ms. Kamali’s Chloé, which has taken the Chloé girl and grown her into a woman.

“The term ‘Chloé girl’ is so connected to how the world perceived the house in the first place,” Ms. Kamali said. “But the word ‘girl’ is reductive. I never want the Chloé woman to be only one thing. No woman is. She has shifting moods and feelings. Ease and optimism always exists with tension. These contrasts and these opposites are what makes everything interesting.”

Including, maybe especially, the shirt on your back.

-

Sports1 week ago

Sports1 week agoNHL trade board 7.0: The 4 Nations break is over, and things are about to get real

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoJustice Dept. Takes Broad View of Trump’s Jan. 6 Pardons

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoHamas says deal reached with Israel to release more than 600 Palestinians

-

Science1 week ago

Science1 week agoKilling 166 million birds hasn’t helped poultry farmers stop H5N1. Is there a better way?

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoChristianity’s Decline in U.S. Appears to Have Halted, Major Study Shows

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoGermany's Merz ‘resolute and determined,' former EU chief Barroso says

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoMicrosoft makes Copilot Voice and Think Deeper free with unlimited use

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoSome Republicans Sharply Criticize Trump’s Embrace of Russia at the U.N.