Entertainment

Marsha Hunt, actress who appeared in more than 50 films before being named as a Communist sympathizer, has died

By the point she was in her early 30s, Marsha Hunt — tall, elegant and well-spoken — had acted in 52 motion pictures, posed on the quilt of Life journal, and been requested by every of the three main TV networks to host her personal present.

However in 1950, the completed, enticing Hunt immediately fell out of favor.

“I used to be ready to listen to from the three networks, and I by no means did,” she recalled in a 2010 interview with NPR. “And my agent defined this with two phrases, which I had by no means heard earlier than: ‘Purple Channels.’ ”

Hunt, who was listed together with 150 different Hollywood personalities in an anti-communist publication that derailed her profession, died Wednesday of pure causes in her house in Los Angeles, in line with Roger C. Memos, director of a 2015 documentary in regards to the actor. Hunt was 104.

Hunt’s movie work additionally dried up in the course of the Purple scare. Over the remaining a long time of her profession, she was solid in solely a dozen extra motion pictures, largely in minor roles.

“I used to be by no means subpoenaed. I used to be by no means a communist. I used to be by no means a determine of public controversy,” Hunt informed an interviewer. “I simply stopped working.”

When Hunt was most in demand, she was a personality actor in motion pictures that included “Delight and Prejudice” (1940), “Blossoms within the Mud” (1941) and “The Human Comedy” (1943).

“I performed 4 previous women earlier than I used to be 30, a Brooklyn showgirl, society snob, schoolteacher, single mom, Military nurse, two nightclub singers, crime lab technician, spoiled heiress, symphony harpist, farm woman and two suicides, amongst others,” she informed movie historian Anthony Slide in his 1999 guide, “Actors on Purple Alert.”

Becoming a member of the board of the Display screen Actors Guild in 1946, Hunt, who had by no means been politically lively, quickly riled conservative board members. When a set decorators’ strike disrupted Warner Brothers, she urged them to stop speculating about alleged communist agitators and focus as an alternative on the employees’ grievances.

“As I spoke, I might see elbows nudging, glances exchanged, as if to say, ‘She should be one!’,” she stated in an interview revealed in “Tender Comrades: A Backstory of the Hollywood Blacklist” (1997).

When the Home Un-American Actions Committee held hearings in 1947 on the political actions of 19 screenwriters and administrators, Hunt was among the many Hollywood celebrities who chartered a aircraft and flew to Washington in protest.

After they returned, a few of the stars, together with Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, backpedaled, calling their involvement ill-advised.

However Hunt and her husband, screenwriter Robert Presnell Jr., supplied no such apologies.

In June 1950, “Purple Channels” denounced 68 actors, 44 writers, 28 musicians, 18 administrators, 11 commentators, three announcers, a music critic, a lawyer and an accountant for his or her alleged communist leanings. They included such celebrated figures as Pete Seeger, Dorothy Parker, Edward G. Robinson, Orson Welles, Edward R. Murrow, Lena Horne and Arthur Miller.

Hunt was listed between author Langston Hughes and director Leo Hurwitz. She was cited for six allegedly unpatriotic actions, together with giving an anti-censorship speech and signing a petition asking that the Supreme Courtroom resolve whether or not famous screenplay writers Dalton Trumbo and John Howard Lawson had been rightly convicted of contempt for refusing to inform HUAC whether or not they had been communists.

“And sure certainly, I had been there, I had executed that, I had stated this or signed one thing, all of them issues I believed in and was amazed to find they had been thought of subversive in a roundabout way,” Hunt informed NPR.

The ‘’Purple Channels” checklist was one among a number of that named individuals within the leisure trade. Lots of these listed discovered little work for years afterward.

Marsha Hunt chats with Roger C. Memos, who made a documentary about her in 2015.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Occasions)

Born in Chicago on Oct. 17, 1917, Marcia Virginia Hunt was the daughter of Earl Hunt, a lawyer and insurance coverage govt, and Minabel Hunt, a voice trainer and organist. She was raised in New York Metropolis and attended personal faculties.

As a youngster, she took drama courses and have become a mannequin. Anticipating an performing profession, she vowed to spell her first identify so her followers would know learn how to pronounce it. Therefore: Marsha.

When she was 17, a few publicists planted an merchandise within the Los Angeles Occasions about “a New York artist’s mannequin” coming to city to go to her uncle.

“I’m right here purely on a trip journey,” she informed The Occasions in 1935. “I’ve no ambition to enter the movies at the moment.”

The story had its desired impact. Studios sought out the unknown Hunt for display screen exams. Later that yr she appeared in “The Virginia Choose,” the primary of 12 movies for Paramount.

She was a co-ed in “Faculty Vacation” (1936), with George Burns, Gracie Allen and Jack Benny. Within the 1939 comedy “Joe and Ethel Turp Name on the President,” Hunt, then 22, modeled an aged character after her household’s housekeeper and a great-aunt in Indiana.

“I used to be fascinated with older ladies’s carriage, the way in which they sat, the way in which they labored their mouths, the way in which they squinted via their glasses,” she informed an interviewer when she was in her 80s.

Hunt labored alongside John Wayne, Laurence Olivier, Lana Turner, Greer Garson and different main stars.

After her point out in “Purple Channels,” she appeared with Charles Boyer and Louis Jourdan in “The Comfortable Time” (1952). Throughout filming, she later recalled, she was pressured to signal a full-page advert declaring her opposition to communism.

She refused.

Whereas Hunt’s movie roles grew sparse, dwell theater was comparatively unaffected by the blacklists. Hunt starred in six Broadway performs and as many as 30 regional productions.

Her final main position was in “Johnny Bought His Gun,” a 1971 antiwar movie based mostly on a guide by Trumbo, the once-ostracized screenwriter. Trumbo, who wrote the scripts for “Exodus” and “Spartacus,” amongst others, additionally directed it.

Over time, Hunt grew to become an activist, engaged on refugee causes for the United Nations, serving to organizations for the homeless in Los Angeles and changing into an early supporter of same-sex marriage. Within the early Eighties, she was named honorary mayor of Sherman Oaks.

Movie buffs honored her at festivals, singling out motion pictures comparable to the noir crime story “Child Glove Killer” (1942) and the early Holocaust indictment “None Shall Escape” (1944). Her profession was captured in Memos’ documentary, “Marsha Hunt’s Candy Adversity.”

At each look and in each interview, she was requested about her offscreen position in “Purple Channels.”

“The one actual remorse I’ve,” she informed NPR, “is that I could also be remembered for having been blacklisted relatively than for the work that I’ve executed as an actor.”

Hunt’s husband Robert Presnell Jr. died in 1976. An earlier marriage led to divorce. Her solely youngster, a daughter, died shortly after start. Based on a discover despatched by Memos, Hunt was attended at her dying by a nephew, actor/director Allan Hunt, and her buddy and govt supervisor, Elizabeth Lauritsen.

Chawkins is a former Occasions employees author.

Movie Reviews

Thelma the Unicorn Movie Review: A reasonably effective, even if predictable pony tale

The new Netflix film, Thelma the Unicorn, is an animated film based on a children’s story of the same name by Aaron Blabey. And like most other children’s stories, it possesses layers of meaning that can resonate with adults as well. The film’s core message of overcoming adversity is timeless, but the narrative unfolds predictably. The story of a pony, who (Brittany Howard) gets bullied in a talent show and overcomes the obstacles to realise her dream of becoming a music hotshot, is your quintessential underdog tale. The setting, the nature of obstacles, and the support system of Thelma may all feel new, but the building blocks of the story and the character arcs feel familiar. There is the initial humiliation that the protagonist faces, followed by her unwavering spirit to overcome any and all challenges, the valuable lessons she learns, and of course, the big triumph. Thelma’s quest to realise her desire for musical recognition through a talent event called SparklePalooza results in the kind of uplifting stage-show end we have seen and experienced in many such films.

Director: Jared Hess

Voice cast: Brittany Howard, Will Forte, Jemaine Clement, Jon Heder, Zach Galifianakis

Streamer: Netflix

Entertainment

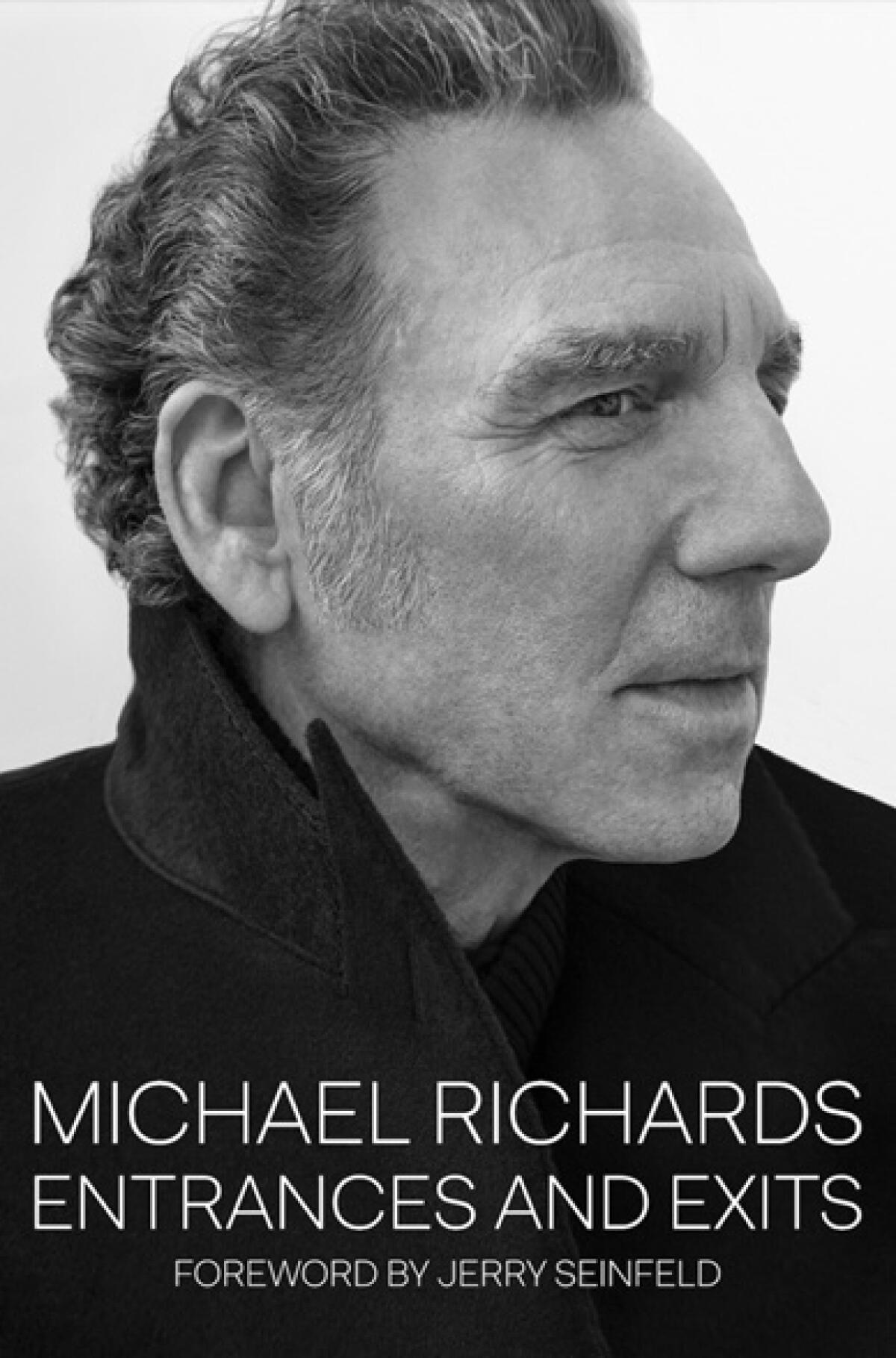

'Seinfeld' star Michael Richards is more than the worst thing that ever happened to them

Michael Richards, who shot to fame as Kramer on the hit sitcom “Seinfeld,” is releasing a memoir, “Entrances and Exits.”

(Marcus Ubungen / For The Times)

On the Shelf

Entrances and Exits

By Michael Richards

Permuted Press: 440 pages, $35

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Michael Richards entered the cultural consciousness, and the apartment next door, as a force of spontaneity named Cosmo Kramer. He was the rubber-limbed, unchained id of “Seinfeld,” the most popular sitcom of its era and a cultural phenomenon cultish in its fervor but too massive to really be considered a cult. Richards and Kramer worked without a net. The energy, the motion, the kavorka forever verged on chaos. But the chaos had a purpose, and it was tremendously popular. Richards won three Emmys for the role, and regularly earned the show’s biggest laughs.

Then, late one November night in 2006, the chaos tipped over into disaster. Performing a surprise set at the Laugh Factory, a venerable Los Angeles comedy club, Richards responded to some hecklers with a viciously ugly tirade. He hurled the N-word about, over and over, turning a night of uncomfortable comedy into the kind of incident that destroys careers. This was early in the era of ubiquitous cellphone cameras, when a horrible mistake could instantly be transmitted around the world. Richards quickly pivoted to damage control, making an appearance via satellite to apologize during his friend Jerry Seinfeld’s visit to “The Late Show With David Letterman.” But the damage was done. He was now widely labeled a racist, and worse.

Richards addresses his night of infamy in his new memoir, “Entrances and Exits,” and once again apologizes. The pop culture mulch machine will quickly reduce the book to soundbites: “Michael Richards says he’s not a racist!” But the Laugh Factory incident is but one tendril of Richards’ book, albeit an important one, tying into the dangerous high-wire act of performance in general and stand-up comedy in particular. It’s the story of a very lonely kid, raised by a working mother, a schizophrenic grandmother and the streets of Southern California; an army veteran who found his life’s purpose on the stage, poured everything into his craft, rose to the height of his profession, never learned to control his rage, flamed out in horrific fashion — and set about slowly rebuilding himself.

It’s also a reminder that everyone is more than the worst thing that ever happened to them — and that stability and comedy don’t always get along.

“It’s what I call the irrational,” Richards, 74, said in a telephone interview from his L.A. home. “We’re constantly being challenged … and anger’s in the midst of it. So it’s always an ongoing endeavor with me. We strive to be persistently rational, but there’s always the irrational, there’s always the mistake, there’s always the pratfall.”

“Public condemnation and humiliation are forms of justice,” Michael Richards writes in his memoir about the response to his racist Laugh Factory rant.

(Marcus Ubungen / For The Times)

Before Kramer, before public shame, there was a child wandering around Baldwin Hills, wondering who his father was and what might have happened to him. The kid soon discovered he liked to perform in drama class. It gave him a way to release the confusion and anxiety inside, and to make people laugh. But the kid still had a restless spirit. He studied acting at the California Institute of the Arts, created an absurdist, highly physical comedy act with his friend Ed Begley Jr. and was drafted into the army in 1970. Stationed in West Germany, he joined the V Corps Training Road Show; he took on the role of a colonel for that theater company. He stayed in character 24/7, even obtaining fake official military identification. It was the start of a lifelong obsession with creating and inhabiting a persona.

By 1989, when fellow former “Fridays” writer-cast member Larry David and Seinfeld had him audition for a new series then called “The Seinfeld Chronicles,” Richards was ready to launch. Much of his character, who was originally called Kessler, was on the page. But Richards built him into a rollicking, three-dimensional creation, right down to the clothes on his back.

“What Kramer wore was all hand-picked by me,” Richards said. “I gathered that wardrobe by combing every secondhand store in Southern California looking for shirt packs. All the clothing is out of the ’60s because my character is still pretty much wearing what he wore then. That’s why the pants are short and so forth, because he’s just a little taller. Everything about the character is justified.”

In “Entrances and Exits” Richards writes that he always considered himself more of a character actor or performance artist than a comedian, though he was also a creature of the comedy clubs on and off throughout his career. His act was never scripted and usually wild — falling on tables, walking onto the stage, futzing with the microphone stand and leaving. More than once in the book Richards uses the word “knockabout” to describe his school of comedy. But he also could be quite disciplined: Between seasons of “Seinfeld” he was often off studying acting in New York, trying to hone his craft.

Onstage, Richards generally went where the spirit moved him. And the spirit could get dark and unpredictable. He was friends with Sam Kinison, a comic whose entire act was based in rage, and there were times when Kinison alarmed Richards with the diamond-like purity of his anger. “He scares me,” Richards writes of his early impressions of Kinison. “I think he’s crazy and I’m heading in the same direction.”

By 2006 “Seinfeld” was in the rearview mirror. Richards’ follow-up series, “The Michael Richards Show,” had been swiftly canceled in 2000. He was a little adrift, and dipping his toe back into stand-up. On Nov. 17, 2006, he took the stage at the Laugh Factory later than usual. He was ill at ease, in angry-comedian mode, walking that razor’s edge between volatile performer and unhappy human. Then he heard the voice from the balcony: “We don’t think you’re very funny!”

“Of course, looking back at it, I wish I had just agreed with him,” Richards writes. “‘Okay, I’m not very funny tonight. Is there anything I can do? Wash your car, mow your lawn? I don’t want you leaving dissatisfied.’ Instead, I take his remark pretty hard. A solid punch below the belt.”

And he snapped — loudly, violently, using some of the ugliest language known to man.

Yes, he is sorry. And he accepts the descent into purgatory that followed. “Public condemnation and humiliation are forms of justice,” he writes. And nothing about his personal rehabilitation seems merely performative. Richards has spent his post-Laugh Factory years learning to live with himself away from the stage (although he still welcomes the occasional acting gig). He has studied the Hindu philosophy of Vedanta in Cambodia. He and his second wife, Beth, had a son, with whom he has finally brought himself to enjoy watching “Seinfeld” (for many years he was haunted by thoughts of how much better his performance could have been). He has fought, and, for the time being, defeated prostate cancer.

Michael Richards says these days, “I sit with the natural world, which seems to be behind most of everything we’re up to.” His memoir, “Entrances and Exits,” is out June 4.

(Marcus Ubungen / For The Times)

He is intent to continue doing what he calls “heart work,” figuring out who he really is and what animates the darkness within. Much like the kid who once roamed Baldwin Hills, he takes daily walks in the mountains of Southern California. “I want to get behind the behind, behind the words, the anger, the person, the cultural conditions and so forth,” he said. “So I sit with the natural world, which seems to be behind most of everything we’re up to.”

Pleas for forgiveness can get boring. “Entrances and Exits” is something else: an accounting of a life and the performances that go into it, for better and worse.

Movie Reviews

In Flames review: Complex tale of patriarchal oppression with a horror edge

Selected cinemas; Cert 15A

‘In Flames’ bears all the usual hallmarks of a grounded social drama. Photo: Blue Finch Film Releasing

Sinister men and malevolent spirits play treacherous mind games with a young Pakistani woman in Zarrar Kahn’s unsettling psychological drama, In Flames. Mariam (Ramesha Nawal, brilliant) and her mother Fariha (Bakhtawar Mazhar, likewise) are in mourning. The latter’s father has died – so, too, has her husband, which means the family is now without a patriarch.

The neighbours won’t like that, and though Fariha wishes her daughter would find a husband, Mariam dreams of becoming a doctor and is dedicated to her studies. That is, until Asad (Omar Javaid), a pushy stranger who showers Mariam with compliments, enters the equation.

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoIs Coppola’s $120M ‘Megalopolis’ ‘bafflingly shallow’ or ‘remarkably sincere’? Critics can’t tell

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoTaiwan grapples with divisive history as new president prepares for power

-

Crypto1 week ago

Crypto1 week agoVoice of Web3 by Coingape : Showcasing India’s Cryptocurrency Potential

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump predicts 'jacked up' Biden at upcoming debates, blasts Bidenomics in battleground speech

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoThe NFL responds after a player urges female college graduates to become homemakers

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoVideo: A Student Protester Facing Disciplinary Action Has ‘No Regrets’

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoA bloody nose, a last hurrah for friends, and more prom memories you shared with us

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoGerman police investigate AfD member Petr Bystron for money-laundering