Business

Your package wasn't delivered? Try living at one of L.A.'s '½' addresses

Casey Hogan had no idea her new address would be so frustrating.

But soon after moving into a granny flat in Van Nuys three years ago, she realized that the fraction in her house number — think: 101 ½ Main St. — was going to be particularly inconvenient in an era of constant deliveries.

Her packages get marked as “address not deliverable” or dropped off at the wrong door. Retail websites that are programmed to reject special characters, including the fraction’s slash, sometimes refuse her shipping address or auto-correct it to another location.

She has tried workarounds to this quirk of Los Angeles geography — most common in dense neighborhoods with duplexes or, as in Hogan’s case, at accessory dwilling units built on preexisting properties. Spelling out the fraction as “one half” has helped, but about a quarter of her packages or food deliveries arrive late or get dropped at someone else’s house.

In the case of a particularly urgent order before a flight, she had Amazon deliver a dog carrier to her mother’s home in Oceanside and drove there to pick it up instead of risking a snafu at her place.

“It’s still a nightmare,” said Hogan, 32, who works as a medical scribe. “Anything that could go wrong has gone wrong.”

In the increasingly deliverable world shaped by consumers’ skyrocketing, post-pandemic expectations that almost anything they want or need should arrive quickly and seamlessly at their doorstep, residents at more than 60,000 Los Angeles addresses like Hogan’s have been left on the sidelines. (Or really, left standing on their stoops, searching endlessly for packages.)

The shared inconvenience grew into a community on Reddit, where people swap tips, such as entering the address as a decimal — 101.5 Main Street — or spelling it out as Hogan does. One person made a more drastic suggestion: “Break down and get a P.O. box.”

Dealing with fractional addresses and other tricky deliveries, such as those behind gates, is equally frustrating — and costly — for retailers, logistics experts said, as well as for shipping companies that move more than 58 million packages a day in the United States.

The average American received about 70% more packages in 2022 than in 2017, according to a Capital One shopping research report. And a recent survey of 300 retail executives by the location data company Loqate found that almost 8% of first-time deliveries in the U.S. failed, costing about $17 per failed order — or roughly $200,000 a year.

Fractional addresses are sometimes written with slashes and other times with decimals — or, as at this home in East Hollywood, both.

(Marisa Gerber / Los Angeles Times)

“They have to deal with such a large amount of packages,” said Blake Droesch, a senior analyst at eMarketer who studies last-mile delivery. “This is not the post office of yore, where you could get an address half right, and the mailman will spend half the day trying to figure out who this letter belongs to.”

Since demand for deliveries spiked early in the pandemic, Droesch noted, there has been a significant shift in what people buy online, from items like new shoes or a laptop — things people didn’t mind waiting a few days to receive — to hygiene products and home essentials needed quickly.

“If you run out of deodorant,” he said, “you kind of need that the next day.”

Ram Bala, an associate professor of business analytics at Santa Clara University, studies the supply chain and is involved in a startup that will use generative artificial intelligence to improve shipping logistics.

Bala said it’s often odd little problems that sound simple to solve — in this case, figuring out how to accommodate fractional addresses — that end up being the trickiest.

“Anytime you try to fix that problem, there are unintended consequences somewhere else,” he said. “It’s a trade-off.”

Retailers don’t appear to be prioritizing a fix for people with fractional addresses, since doing so would require removing rigid formatting parameters built into software to ensure that normal addresses get entered correctly, Bala said.

In Los Angeles, which has about 1 million residential addresses, the roughly 60,700 fractionals are relative rarities. They’re concentrated in densely populated neighborhoods such as Boyle Heights, East Hollywood and Pico-Union, according to the city’s Bureau of Engineering, which oversees the handling of address numbers.

“The use of fractional numbers is discouraged and should only be used as a last resort,” a primer on the bureau’s website says.

A spokesperson for the city said the reticence to assign fractional addresses — which are often, but not always, ½ and never go beyond ¾ — stems from conversations with residents worried about not only confusing delivery drivers and visitors but the effect on property values. Still, it’s sometimes the best alternative when squeezing new units between existing ones.

The phenomenon isn’t unique to L.A.

Only about 60,700 of Los Angeles’ 1 million residential addresses have fractions.

(Marisa Gerber / Los Angeles Times)

Pockets of other big cities where large, historic buildings were divided into smaller dwellings, such as New York and Philadelphia, also have fractional addresses. And in an even more complicated twist detailed in a piece by Colorado Public Radio, the city of Grand Junction, Colo., has fractions in its street names, creating perplexing intersections such as C ½ and 28 ¾ roads.

Despite the delivery headaches, fractional addresses can carry a whimsical charm, often drawing comparisons to Platform 9 ¾, the fictional London train stop where students in the Harry Potter series caught the Hogwarts Express.

But for Juan Crespo, who started the Reddit thread asking for tips about living at a fractional address, it was more annoying than alluring.

Before moving into a unit in a Highland Park quadplex in 2021, the 32-year-old research scientist tried to change his shipping address with online retailers he used frequently, including Southwest Airlines and Target, where he and his spouse had created their wedding registry.

But the sites kept rejecting the slash.

He eventually called and, after a wait, got a Target employee to manually add the “½” to his address; by then, he said, several gifts, including a $300 stand mixer, had already been sent.

When ordering from DoorDash and Uber Eats, he said, his address would often be automatically switched to a different location a few blocks up, requiring him to enter a neighbor’s address instead.

“It was just a pain,” said Crespo, who has since relocated to Michigan and settled into a home with a full address number. “I’m glad we don’t have to deal with that anymore.”

For Hogan, who lives in the ADU in Van Nuys, the annoyance remains.

A few months ago, she posted to an online help forum, asking Google to have her fractional address added to Google Maps, since many retailers use the company’s mapping software to handle shipping logistics, and a problem there can create a ripple effect of issues on other sites.

“I have to resort to entering my neighbor’s address and hoping I can intercept the delivery person,” Hogan wrote. “HELP!”

A member of Google’s Product Experts Program, a group of volunteers who answer questions in exchange for perks from the company, quickly responded to Hogan saying that only an employee can add an address with a slash to the map. A volunteer asked her to upload a photo of her driver’s license or utility bill showing her address, but Hogan felt uncomfortable doing so and abandoned the effort.

She can easily rattle off a list of packages that never arrived or were initially dropped off somewhere else: workout clothes, two pairs of shoes from Nike, a showerhead from Jolie Skin Co. And she has gotten used to filing claims with shipping companies after getting notifications with pictures showing packages left in unfamiliar doorways. She bought a Ring doorbell camera and enabled the package notification feature, so she has proof that a delivery never arrived.

So many of her food deliveries got messed up, she said, that she set up a rack outside her gate with a sign that reads, “Leave food here.”

These days, she prefers to shop in person whenever possible and thinks twice before buying anything online — a hesitance, she admits with a laugh, that comes with a silver lining.

“I guess it does save me money.”

Business

Dominic Ng: Philanthropist banker, inclusion practitioner

The year 2023 was especially cruel to regional banks in California. Repeated interest rate hikes by the Federal Reserve exposed the poor bets and hubris of regional highfliers like Silicon Valley Bank and First Republic. Those banks capsized, which sparked bank runs, which wiped shareholders out.

One regional bank, however, smoothly sailed on: East West Bank, helmed for more than 30 years by Dominic Ng, who champions the durable power of steady growth. “We’re prudent and cautious, but very entrepreneurial,” he said from his office at East West headquarters in Pasadena. “The way you win in banking is not through shortcuts. It’s a long game.”

‘His leadership has transformed the bank, transformed philanthropy and what business leadership looks like in L.A.’

— Elise Buik, United Way of Greater Los Angeles’ chief executive

The result has been accolades: No. 1 best-performing bank in its size category last year from S&P Global Market Intelligence and No. 1 performing bank in 2023 by trade publication Bank Director. The diversity of its board of directors — Latino, Asian, Black, female and LGBTQ+ all represented — has also won acclaim.

Steady profits enabled East West to become one of Los Angeles’ top civic benefactors. Ng has been especially active with the United Way of Greater Los Angeles for more than 25 years and is credited with championing a strategic change in direction to more effectively serve the city’s desperately poor, while persuading more of the city’s richest residents to pitch in.

Discover the changemakers who are shaping every cultural corner of Los Angeles. This week we bring you The Money, a collection of bankers, political bundlers, philanthropists and others whose deep pockets give them their juice. Come back each Sunday for another installment.

“His leadership has transformed the bank, transformed philanthropy and what business leadership looks like in L.A.,” said Elise Buik, the United Way chapter’s chief executive.

Born to Chinese parents in Hong Kong in 1959, the youngest of six children, Ng has been chief executive of East West Bank since 1992 and expanded on the bank’s original mission of financing Chinese immigrants who in the 1970s found it difficult to qualify for loans through the usual channels. It’s now the largest publicly traded independent bank based in Southern California, serving an economically and ethnically diverse clientele. On the world stage, Ng serves as co-chair of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Business Advisory Council.

Ng, 65, worries about the future of philanthropy in Los Angeles. He longs for the “good old days” when business chiefs didn’t think twice about pitching in to help the city’s less fortunate.

“Today, the pressure is on for [immediate] return to shareholders,” and people running companies have to respond to shareholders who seem to “care less every year” about civic responsibility.

More young, monied tech and finance hotshots would do well to take some cues from business leaders like Ng.

More from L.A. Influential

Business

Mark Suster: The face of L.A. venture capital

Mark Suster, photographed at the Los Angeles Times in El Segundo on Sept. 8.

Cancer-fighting robots. AI-powered baby monitors. The future of American shipbuilding.

These are the kinds of startup ideas that get Mark Suster out of bed in the morning, into his Tesla, and down to the Santa Monica offices of Upfront, the venture capital firm he joined 16 years ago.

“There’s that old saying — the future is already here, it’s just unevenly distributed,” Suster said. “My job lets me see where the world’s going five years before the general population.”

Discover the changemakers who are shaping every cultural corner of Los Angeles. This week we bring you The Money, a collection of bankers, political bundlers, philanthropists and others whose deep pockets give them their juice. Come back each Sunday for another installment.

But Suster, 56, didn’t become the face of the L.A. venture capital scene thanks to his day-to-day investing. He got there by throwing a party called the Upfront Summit.

Every year, Suster’s splashy tech conference takes over an iconic L.A. location. One year, it’s at the Rose Bowl. Another year, it’s at a retreat center high in the Santa Monica Mountains. There are zip lines, hot air balloons, and, among the talks with tech founders about software and product development, fireside chats with celebrities, politicians and authors (Lady Gaga, Katy Perry and Novak Djokovic graced the stage this year).

The razzle-dazzle is part of the draw, and Suster clearly relishes his role as emcee (“I was a theater kid — I still love going to the theater,” he said.)

‘My job lets me see where the world’s going five years before the general population.’

— Mark Suster

But the real appeal comes down to cash. Suster’s strategic move was to invite not just venture capital investors, but the people who invest in venture capital investors. Called limited partners, these are the managers of pensions, sovereign wealth funds and other giant pools of money that want to tap into the tech market. By making sure they’re on the guest list, Suster has made the summit one of the easiest places in America for fellow venture capitalists to raise a new fund.

The summit loses Upfront money. When Suster started it in 2012, it cost around $300,000. In 2022, costs hit $2.3 million, Suster said, with a handful of sponsors chipping in to cut the losses. But throwing the premiere professional party in California comes with intangible benefits, like bringing in deals that would otherwise leave out Upfront and other L.A. funds and founders.

The 2024 party was a little scaled back, now that higher interest rates have throttled the fire hose of money that went into venture capital during the last decade. But Suster says that he welcomes the less frothy environment. “I’m having a lot more fun now,” he said, investing in founders “looking to build real businesses.”

More from L.A. Influential

Business

Steve Ballmer: NBA owner in search of a miracle

He sits in a conspicuous baseline seat, where he cheers like nobody’s watching.

The large balding man in long sleeves roars with every splashed basket, gestures with every scintillating pass, face reddening, arms flailing, celebrating so hard he once ripped a hole in his dress shirt.

He could be any die-hard Clippers fan, with one exception.

He owns the team.

Steve Ballmer is the perfect symbol of the power of Hollywood hope, the strength of California dreaming and the resilience of those who come here searching for a miracle.

Discover the changemakers who are shaping every cultural corner of Los Angeles. This week we bring you The Money, a collection of bankers, political bundlers, philanthropists and others whose deep pockets give them their juice. Come back each Sunday for another installment.

Ranking eighth on the Forbes 500 list with an estimated net worth north of $120 billion, Ballmer could afford to buy any sports team in any league.

He chose to buy the Clippers, spending $2 billion in 2014 for a perennial loser and one of five teams to never reach the NBA Finals.

“A team comes up for sale in a city I love that’s near me?” said Ballmer, 68, a former Microsoft executive who lives in Washington state. “You say, ‘OK, but it’s the Clippers,’ and my theory is, you can do anything if you put your mind to it.”

As the richest owner in North American professional sports, he had the wealth and influence to move the bedraggled franchise to a city far away from the big brother Lakers, perhaps even into his adopted hometown of Seattle.

‘It was clear to me, we had to have our own home, our own identity.’

— Clippers owner Steve Ballmer

Yet he doubled down and not only kept the Clippers in town but spent another $2 billion to build his own arena: the glitzy Intuit Dome, which is scheduled to open in October in Inglewood.

“It was clear to me, we had to have our own home, our own identity,” Ballmer said.

Cynics would describe his ownership of the Clippers as charity work, but his real philanthropy has had an even larger impact in the region, with his Ballmer Group investing hundreds of millions of dollars in everything from inner-city businesses to the renovation of 500 Clipper Community Courts in diverse pockets of the city.

“Impacting kids is the kind of thing that pulls at my heart,” Ballmer said. “A fan will tell me that he drove past a Clipper court and I’ll think, that’s really, really, really cool.”

Ballmer is accessible, generous and, most of all, the head cheerleader for a drowned-out swath of a Lakers-owned city.

“I love our die-hard fans,” he said. “I love the culture of c’mon, we have a chip on our shoulder, we’ve got something to prove, we’ve never done it before, c’mon!”

It is a Thursday afternoon early in the 2023-24 NBA season and Steve Ballmer is shouting into the phone, because of course he is, the sound of undying faith, the voice of a true believer, c’mon!

More from L.A. Influential

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoNewson, Dem leaders try to negotiate Prop 47 reform off California ballots, as GOP wants to let voters decide

-

News1 week ago

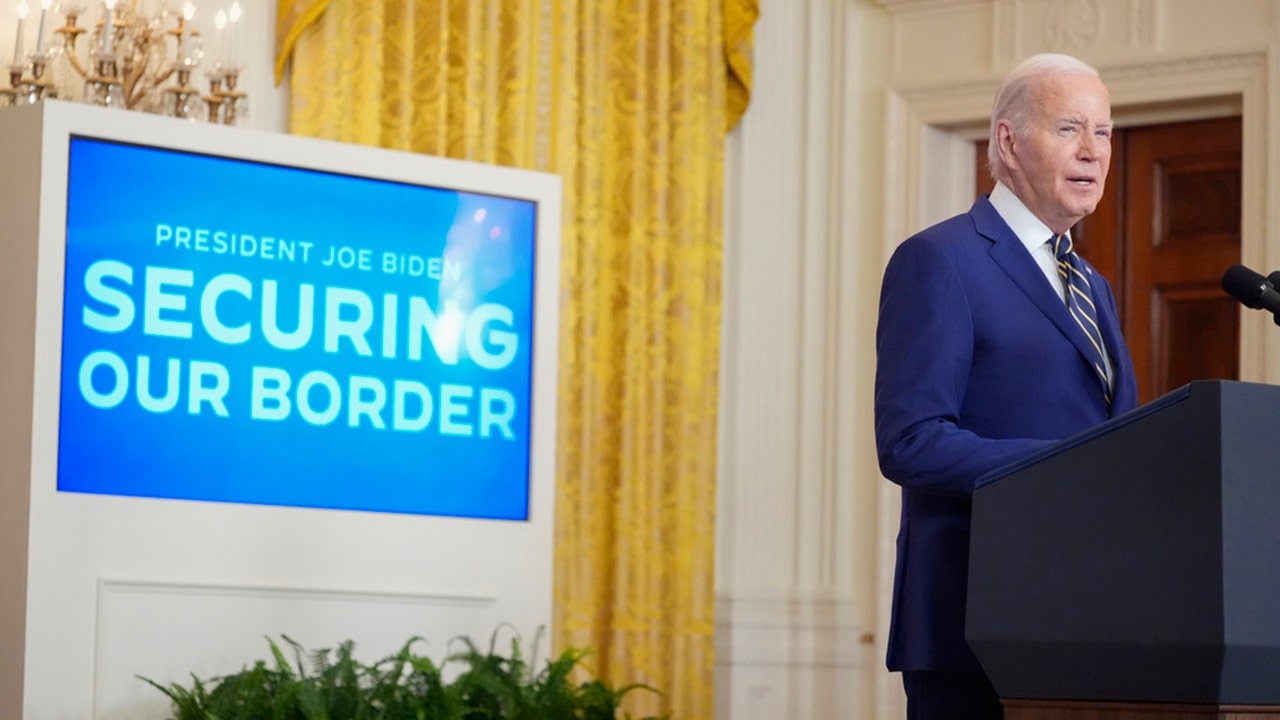

News1 week agoWould President Biden’s asylum restrictions work? It’s a short-term fix, analysts say

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoDozens killed near Sudan’s capital as UN warns of soaring displacement

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoRead Justice Clarence Thomas’s Financial Disclosures for 2023

-

World1 week ago

World1 week ago‘Bloody policies’: Bodies of 11 refugees and migrants recovered off Libya

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoEmbattled Biden border order loaded with loopholes 'to drive a truck through': critics

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoGun group vows to 'defend' Trump's concealed carry license after conviction

-

Politics7 days ago

Politics7 days agoShould Trump have confidence in his lawyers? Legal experts weigh in