Lifestyle

The Okalolies of Old Year's Night: Celebrating tradition on the world's most remote inhabited island

A group of Okalolies head toward a house belonging to one of their own in Edinburgh of the Seven Seas on Tristan da Cunha, in the South Atlantic Ocean, on Dec. 31, 2023. New Year’s Eve, or Old Year’s Night as it’s known on the island, is a chance for the whole community to come together.

Julia Gunther

hide caption

toggle caption

Julia Gunther

A group of Okalolies head toward a house belonging to one of their own in Edinburgh of the Seven Seas on Tristan da Cunha, in the South Atlantic Ocean, on Dec. 31, 2023. New Year’s Eve, or Old Year’s Night as it’s known on the island, is a chance for the whole community to come together.

Julia Gunther

Dec. 31, 2023, shortly before 2 p.m. Gray, low-hanging clouds obscure the tops of green cliffs that tower over Edinburgh of the Seven Seas, a village of 238 people and the sole settlement on the island of Tristan da Cunha.

Tristan lies in the middle of the South Atlantic ocean, a famously wild and unpredictable expanse of water.

The closest inhabited place is St. Helena, the island where Napoleon Bonaparte lived out the last of his days that sits 1,514 miles to the north; around 2,434 miles to the west lies Montevideo, the capital of Uruguay; to the south, you’ll find nothing but cold ocean and icebergs until you hit Antarctica; and 1,732 miles due east lies Cape Town, South Africa.

Buffeted by blustery South Atlantic gusts, I follow brothers Dean and Randal Repetto as they make their way through the deserted streets. We’re the last to arrive at a small sawmill nestled in between two corrugated iron warehouses.

An Okalolie poses inside a clandestine changing room — a small sawmill. The Okalolies are part of a type of visiting custom known as mumming in which young men disguise themselves, visit homes and engage in playful pranks — mainly at Christmas and on New Year’s Eve — that have existed in Europe for the past 500 years.

Julia Gunther

hide caption

toggle caption

Julia Gunther

We walk into an impromptu, clandestine changing room, home of this year’s Okalolies of Old Year’s Night. Old skirts and masks and cans of spray paint that are ordinarily used by islanders to mark their sheep line both sides of the sawmill. The other participants are already getting dressed. The goal is to disguise oneself as fully as possible and to remain anonymous throughout the day.

On Tristan da Cunha, the Okalolies only come alive on Dec. 31, hours before the start of the new year. For 26-year-old Dean and 21-year-old Randal, who were both born on Tristan and have lived here their entire lives, Old Year’s Night is an annual tradition they look forward to.

Photographer Julia Gunther and I asked if we could join the Okalolies for the day, which they agreed to.

An ecosystem of global significance

A single dormant volcano reaching 6,765 feet above sea level, Tristan da Cunha is part of a remote archipelago with the same name. Other than Tristan, the islands — Inaccessible, Nightingale, Middle and Stoltenhoff — are uninhabited, except for a South African manned weather station on Gough Island.

Two of the islands were awarded UNESCO World Heritage status for their outstanding natural beauty and universal value: Gough Island in 1995 and Inaccessible Island in 2004.

The Okalolies pose with Janine Lavarello, who holds Emily Swain, after she stopped to say hello. Riaan Repetto, Emily’s father, is the Okalolie on the far right.

Julia Gunther

hide caption

toggle caption

Julia Gunther

The waters around Tristan are some of the richest and pristine in the world, and the archipelago is home to the world’s only breeding colonies of spectacled petrels and Atlantic yellow-nosed albatrosses, as well as 37 endemic species of plants and the world’s largest population of sub-Antarctic fur seals.

In a testament to the significance of the archipelago’s flora and fauna, the waters surrounding Tristan da Cunha were declared a marine protection zone in 2020 by the island’s government along with the U.K. — the largest in the Atlantic Ocean.

An archipelago of islands difficult to reach

The first thing most people will tell you about traveling to Tristan Da Cunha is just how hard it is to get there. For many, though, that’s part of the appeal.

Depending on the weather, the trip from Cape Town can take seven days across flat, calm water, or up to two weeks rolling and pitching in the strong westerly winds that blow sailing ships from Europe to the East Indies or Australasia.

Most will have traveled from Cape Town on the MFV Edinburgh or MFV Lance — two lobster fishing vessels that offer the only regular connection to Tristan. A third far larger ship, the Agulhas II, makes the trip once a year.

A group of Okalolies share a drink while on a break from roaming around the village. The Okalolies are often invited for a drink by “brave” members of the community who open their doors to the group. Many are also fathers and will pass by their own houses during the day’s festivities.

Julia Gunther

hide caption

toggle caption

Julia Gunther

A lucky few will have arrived here on one of the cruise ships that regularly cross the South Atlantic as part of their annual relocation from the Northern to Southern hemispheres.

Our own trip was a good example of the uncertainties islanders and visitors face to reach the island. After spending a month in Cape Town waiting for space on one of the regular ships, we decided to risk hitching a ride on an expedition cruise ship, the SH Diana.

After five days at sea, we arrived at Tristan to find the only harbor closed due to heavy swells. Luckily, the Edinburgh was fishing nearby and we were able to transfer to her to wait out the weather. After another five days, the seas were calm enough for us to land. Had the Edinburgh not been where she was, we would have ended up at the cruise ship’s final destination, in Ushuaia, Argentina.

Other than day tourists from visiting yachts or cruise ships — the latter of which can momentarily double or even triple Tristan’s population — and a busy few weeks at the end of August when the largest regular ship of the year, the SA Agulhas II, drops off new expats, returning islanders and a few tourists, the island sees very few visitors.

Several Okalolies peer into the kitchen of a house belonging to one of their own. Although they are careful not to frighten children and the elderly too much, they are expected to make light mischief, and will attempt to soak any woman they find with a garden hose.

Julia Gunther

hide caption

toggle caption

Julia Gunther

On Tristan da Cunha, a night for making ‘mischief’

You’d be forgiven for thinking that it’s impossible for a group of 15 young men to keep anything a secret in a community this small, but that is exactly what we — 16 Okalolies in total — manage to pull off.

Okalolies are always male. There is no selection process. “You just need to be brave enough,” explains Randal, who himself was 15 years old when he first took part.

Young boys see the tradition as a rite of passage. Randal remembers putting on an Okalolies mask as a child. “I looked into the mirror and frightened myself to death,” he laughs as we get into our costumes. Now, he can’t wait to find others to scare.

One of the first years that Albert Green, 67, was an Okalolie, he and a friend were getting dressed in his father’s shed. “We had our backs to one another and when we turned ’round, we both jumped with fright,” Albert says.

At 94, Gladys Lavarello is one of the oldest Tristanians on the island. She remembers a young woman called Liza, who, during one Old Year’s Night back in the 1970s, dressed up as an Okalolie and managed to fool all the men into thinking she was one of them. “She was dancing around with them and they didn’t even know it was her,” Gladys recalls with a smile.

Like his older brother, Randal is a seasoned Okalolie. Now, it’s their job to show Tristan Glass, 16, Kieran Glass, 18, and Calvin Green, 15, how it’s done. “The young guys learn by watching us older ones. They just follow us and pick it up as they go on,” Dean explains.

Kieran Glass (left) waits for a drink while Tristan Glass checks on Jake Swain, who is fast asleep. Most children are terrified of the Okalolies and will cry or hide when they approach. Jake, however, was utterly unimpressed and slept through most of the day.

Julia Gunther

hide caption

toggle caption

Julia Gunther

Although the village fully expects them to appear and cause havoc — as they have for at least a hundred years — exactly who will be an Okalolie and where they will get dressed remains a closely guarded secret.

“We don’t want to let people know where we’ll be coming from, as it makes it scarier,” Randal explains.

Randal knows the look he’s going for. “Anything that looks ragged and scary, especially zombie-like,” he tells me as we walk through the sawmill.

Dean has been an Okalolie for the last 13 years, but he still gets excited. “I feel really energetic,” he says. “I’m ready to look scary and roam the village, knocking on doors and frightening people.”

Some Okalolies, like Randal, Dean and 36-year-old Shane Green, planned their looks days before and have brought their own masks or dresses — Shane has worn the same costume for the past 10 years.

Others, including me, design their outfits on the spot, picking from an extensive collection of masks ordered from the U.K. and South Africa by a community development fund — which helps pay for and promote island traditions — as well as old skirts and coats and bits of worn workwear.

A group of Okalolies — Calvin Green (from left), Dean Repetto, Christopher Swain, Shane Green, Kieran Glass, Cedric Swain and Callum Green — take a break from roaming around the village. Roaming normally lasts a few hours, and the men will stop for breaks at friendly houses to cool off before putting their masks back on.

Julia Gunther

hide caption

toggle caption

Julia Gunther

I choose a white disposable coverall — which I am encouraged to “personalize” with green and orange spray paint — and a black and red cape. For a mask, I pick out an alien-type thing.

I’m told that Okalolies don’t speak, as this would give away our identities. The silence also adds to our eeriness — a masked group of young men, marauding through the village, looking for “mischief.”

As we head out onto the empty streets of Edinburgh of the Seven Seas, a few last islanders hurry past.

We communicate through hand signals, whistles and whispers, but we can make noise by banging on windows and doors, blowing on horns and playing whatever instrument is at hand — this year, it was a toy accordion and a child’s tambourine.

We decide as a group which houses to visit. Some have made arrangements with the residents, who allow us to frighten their children or invite us in for a beer or cider.

Tristan da Cunha’s Head of Tourism, Kelly Green, greets the Okalolies with her daughter Savanna after they’ve arrived at their home. Moments after this image was taken, Kelly was soaked with water from a garden hose. Kelly’s husband, Shane, was one of the Okalolies, and Kelly had trouble figuring out who her husband was before he finally revealed himself.

Julia Gunther

hide caption

toggle caption

Julia Gunther

A rich and eclectic history

Despite being discovered in 1506 by Portuguese Admiral Tristaõ da Cunha, who named the main island after himself, Tristan da Cunha wouldn’t be permanently inhabited for another 300 years.

In 1810, Jonathan Lambert, from Salem, Mass., claimed the archipelago as his own and renamed them the “Islands of Refreshment” in hopes of attracting passing ships in need of fresh water and supplies.

Six years later, in 1816, Tristan da Cunha was annexed by the British, who were worried the French would use the island as a staging post for freeing Napoleon from his imprisonment on St. Helena.

Another major concern was the possibility of American occupation. During the War of 1812, Tristan had served as a base point for American ships to disrupt British maritime activities. Interestingly, the final naval engagement of that war was fought near Tristan in 1815, just a year before the British arrived.

Shop-bought masks and cans of spray paint — normally used to tag sheep — lie ready to be used inside the Okalolies’ clandestine changing room: a small sawmill. The Okalolies use a mix of shop-bought items, old dresses and coats to put together their outfits. The goals are to disguise themselves as scarily as possible and to remain anonymous throughout the day.

Julia Gunther

hide caption

toggle caption

Julia Gunther

When the British garrison departed a year later, three men, led by Corporal William Glass, opted to stay behind. They embarked on an extraordinary venture dubbed “the firm,” grounded in a formal agreement for communal living.

This document, now kept at the British Library, entailed equal distribution of shares and provisions, equal division of profits, shared responsibility in covering expenses, and a commitment to equality without any individual islander holding superiority over another.

Although now a part of the British Overseas Territories, much of the independent spirit captured in Glass’s document is still present on the island today.

A tradition of uncertain origins

The Okalolies are part of a type of visiting custom known as mumming or guising, in which young men disguise themselves, visit homes and engage in playful pranks — mainly on Christmas and New Year’s — that have existed in Europe for the past 500 years.

Although she can’t remember how or why the Okalolies got their start on her island, 94-year-old Gladys Lavarello knows they existed when she was a little girl. “The men would dress up and come ’round, singing and dancing. Then they’d take their masks off,” she tells me in her living room, a few weeks later.

“My father would go ’round with a wheelbarrow and a pitchfork and say that he was cleaning up the mess,” she adds with a laugh.

There is no academic consensus on the origins of the name for the tradition here. It could be derived from the Afrikaans words “Olie Kolonies,” meaning “old ugly men” — Cape Town, South Africa, has long been the main port of call for ships traveling to Tristan.

According to Peter Millington, a retired research fellow at the University of Sheffield who has studied house-visiting customs around the world and who took part in the Okalolies tradition in 2019, the Okalolies are likely “an amalgam of the customs of the home countries of the original settlers, including families no longer present on the island.”

An Okalolie peers through the window of a house, looking for children to frighten. Tristanian women try to outsmart the Okalolies by hiding in groups behind locked doors. Where no “victims” can be found, Okalolies enter the homes of families who have left their doors unlocked.

Julia Gunther

hide caption

toggle caption

Julia Gunther

“The name might have been introduced by transient expat residents, or it might simply have been made up on the island,” Millington offers.

New Year’s Eve used to be called Old Year’s Night in much of Scotland. Corporal William Glass, one of the three British soldiers who elected to stay on Tristan after the garrison departed in 1817, hailed from Kelso, Scotland, where “Auld Year’s Nicht” was still being celebrated in 1923.

Old Year’s Night is also a direct translation from the Dutch Oudejaarsavond. Peter Green, formerly Pieter Groen, from the Netherlands town of Katwijk, was another early settler who remained on the island after his ship, the Emily, wrecked on the coast in October 1836.

The oldest known account referring to the Okalolies tradition on Tristan da Cunha — albeit not by name — is detailed in K.M. Barrow’s book, Three Years In Tristan Da Cunha, and dates back to 1907.

An Okalolie dressed as King Charles III walks out of their clandestine changing room. In honor of the king’s coronation last year — Tristan da Cunha is a British overseas territory — two participants transformed themselves into the king and queen.

Julia Gunther

hide caption

toggle caption

Julia Gunther

For Tristanians, a tradition that’s expected and — for some — still feared

As with most long-lived cultural practices, the Okalolies’ tradition has changed over time. When Gladys was a child, it was predominantly about celebrating the end of the year.

“They used to fire guns to announce they was coming ’round,” Gladys remembers. “We didn’t have much in those days, but we’d always make sure there was milk for them, and if we had a little flour, we’d make them a cake.”

Initially, participants didn’t wear masks but would paint their faces, and the tradition supposedly was teetotal, whereas more recently, alcohol is consumed throughout the day.

“The whole island would dress up,” Albert Green recalls. “We’d go to every house and wouldn’t finish till the next morning.”

Over time, the Okalolies have gotten smaller in number, more mischievous, their outfits more frightening, and the day itself more focussed on scaring people rather than visiting homes.

More recently, homemade masks were incorporated, and nowadays, many wear shop-bought latex horror products.

Although all Tristanians are intimately familiar with the Okalolies, some remain genuinely afraid and hide inside their homes when they know they’ll be out on the streets.

On this Old Year’s Night, we roam together as a group for a few hours, during which we stop for breaks at friendly houses to cool off. Luckily, the weather was unseasonably cold for summer in the Southern Hemisphere — walking up the settlement’s steep roads makes wearing latex masks and multiple layers of tweed and plastic outfits a hot and stuffy experience.

Then, silently and suddenly, we split up, with smaller bands roaming between houses searching for “victims,” almost exclusively women or girls.

An Okalolie poses with Savanna Green. After quickly taking off his mask to identify himself, the two posed for a picture, like they’ve done every year since Savanna was a little girl.

Julia Gunther

hide caption

toggle caption

Julia Gunther

Tristanian women try to outsmart us by hiding in groups behind locked doors. Where no “victims” can be found, we enter the homes of families who have left their doors open.

Chantelle Repetto, 18, tells me she’s been afraid of the Okalolies for as long as she can remember. “Being scared is normal — we don’t know what the boys will do,” she explains.

Rachel Green, 25, is not as frightened as she used to be, but she’ll still run away when she sees them. “They used to throw people in the pool or in the flax,” she says with a laugh, referring to the now-invasive plant first introduced to the island in the 19th century that’s used to provide thatching materials for roofs. “But now they really only wet you with a hose.”

Although some villagers are genuinely afraid of being caught, the Okalolies tradition is all in good fun.

“During Old Year’s Night, the whole community comes together,” explains Chief Islander James Glass — a Tristanian elected by the people of Tristan every three years who represents their interests alongside the Island Council.

“As we’ve become more Westernised; we’ve lost much of our culture,” Glass continues. “The Okalolies are an established tradition that we want to maintain.”

We’re careful not to frighten children and older adults too much, and briefly remove our masks to calm scared children. In a community this small, chances are high that one of the Okalolies will confront their own son or daughter.

After removing his mask to reveal himself, Julian Repetto holds and comforts his daughter, Makayla. When this did not calm the little girl, the other Okalolies followed suit. The Okalolies are careful not to frighten children and the elderly too much. Some islanders, however, are genuinely afraid and will lock themselves inside their houses.

Julia Gunther

hide caption

toggle caption

Julia Gunther

After two hours of knocking on windows and spraying water, I join Randal and Tristan as they rush back to the sawmill and quickly change into a new set of outfits. In honor of King Charles III’s coronation, Tristan transforms himself into a king, and Randal into his queen.

Together with a “royal guard,” King Tristan, Queen Randal and I climb onto the trailer of a waiting decorated tractor.

First, our procession heads to the residence of Administrator Philip Kendall — the U.K. representative on the island — to collect his wife, Louise. Then we move on to James Glass’ house — to pick up his wife, Felicity.

Our passengers safely seated on two armchairs in the trailer, we escort our guests to Prince Philip Hall, the building that houses the village hall and the only pub on the island. There, the waiting administrator and chief islander, along with the entire village, wait to welcome us.

The Okalolies’ tractor arrives at the Prince Phillip Hall, home to the village’s town hall and the only pub on the island, to deliver King Charles and his queen. After they’ve roamed around the community for a few hours, the Okalolies pick up a tractor and trailer to collect the wife of the U.K.’s representative on the island, as well as the wife of the Chief Islander.

Julia Gunther

hide caption

toggle caption

Julia Gunther

It is only now that we finally reveal ourselves. Then, it’s time for dancing, barbecues — or braais, as they’re known on Tristan — and, at midnight, the ringing of the fishing gong, an old gas bottle suspended from a rope and hit with a hammer or metal bar.

Although Randal, Dean and the other Okalolies don’t yet know where they’ll meet to get dressed for next year’s Old Year’s Night, they’ll do their best to keep it a secret. Above all, Dean, like Chief Islander James Glass, is keen to carry on the tradition passed down by his ancestors.

“We frighten the old year out and bring the new year in.”

The Okalolies take part in a traditional Pillow Dance after arriving at Prince Phillip Hall. It’s only now that the Okalolies finally reveal themselves. Then, it’s time for dancing, barbecues — or braais, as they’re known on Tristan — and, at midnight, the ringing of the fishing gong, an old gas bottle suspended from a rope and hit with a hammer or metal bar.

Julia Gunther

hide caption

toggle caption

Julia Gunther

Nick Schonfeld divides his time between writing children’s books and working on stories about affordable health care, gender equality, education and distributive justice.

See more of Julia Gunther’s work on her website or follow her on Instagram: @juliagunther_photography.

Catie Dull photo edited and Zach Thompson copy edited this story.

Lifestyle

The debate over “LatinX” and how words get adopted — or not

Word Wars: Wokeism and the Battle Over Language – John McWhorter

YouTube

Part 2 of the TED Radio Hour episode The History Behind Three Words

New terms — like LatinX — are often pushed by activists to promote a more equitable world. But linguist John McWhorter says trying to enforce new words to speed up social change tends to backfire.

About John McWhorter

John McWhorter is an associate professor in the Slavic Department at Columbia University. He is the host of the podcast Lexicon Valley and New York Times columnist.

McWhorter has written more than twenty books including The Power of Babel: A Natural History of Language, Words on the Move: Why English Won’t – and Can’t – Sit Still (Like, Literally) and Nine Nasty Words. He earned his B.A. from Rutgers, his M.A. from New York University, and his Ph.D. in linguistics from Stanford.

This segment of the TED Radio Hour was produced by James Delahoussaye and edited by Sanaz Meshkinpour. You can follow us on Facebook @TEDRadioHour and email us at TEDRadioHour@npr.org.

Web Resources

Related TED Bio: John McWhorter

Related TED Talk: 4 reasons to learn a new language

Related TED Talk: Txtng is killing language. JK!!!

Related NPR Links

Latinx Is A Term Many Still Can’t Embrace

Why the trope of the ‘outside agitator’ persists

Next U.S. census will have new boxes for ‘Middle Eastern or North African,’ ‘Latino’

Lifestyle

Modern death cafes are very much alive in L.A. Inside the radical movement

In a second-story room in Los Feliz’s Philosophical Research Society, about a dozen people sit in a circle. Many of them are here for the first time and not entirely sure what to expect. The sandwich board sign in the courtyard below offers only a cryptic hint: “Welcome! Death cafe meeting upstairs.”

As the group settles in on this Thursday afternoon in May, organizer Elizabeth Gill Lui lays out the only two directives: “have tea and cake, and talk about death.”

Lui, a 73-year-old artist who wears chunky jewelry and bold glasses, starts by reading a passage from the musician Nick Cave’s recent memoir. It’s about how, in the face of staggering grief, speaking and listening can be a form of healing — which is ultimately what Lui hopes will transpire over the next couple of hours, in this room decorated with patterned carpets and tall bookcases.

“The tradition in Southern California has long been about the journey. Making the most of the journey creatively, playfully, intellectually. That’s what I also like about the death cafe.”

— Elizabeth Lui, artist and organizer of a twice-monthly death cafe at the Philosophical Research Society

To initiate the exchange, she instructs the group to “go around in a circle and say what brought you to death cafe.” It’s a simple enough question, but one that elicits complex, deeply personal responses. Some attendees say they’ve come because they’re struggling with how to care for aging parents, or because they lost a loved one during the pandemic. Others have recently been through a life transition — a move back home, a college graduation, recovery from an illness. Or they’re wrestling with anxieties about their mortality. No matter the reason, everyone seems to be seeking some form of comfort, connection and community.

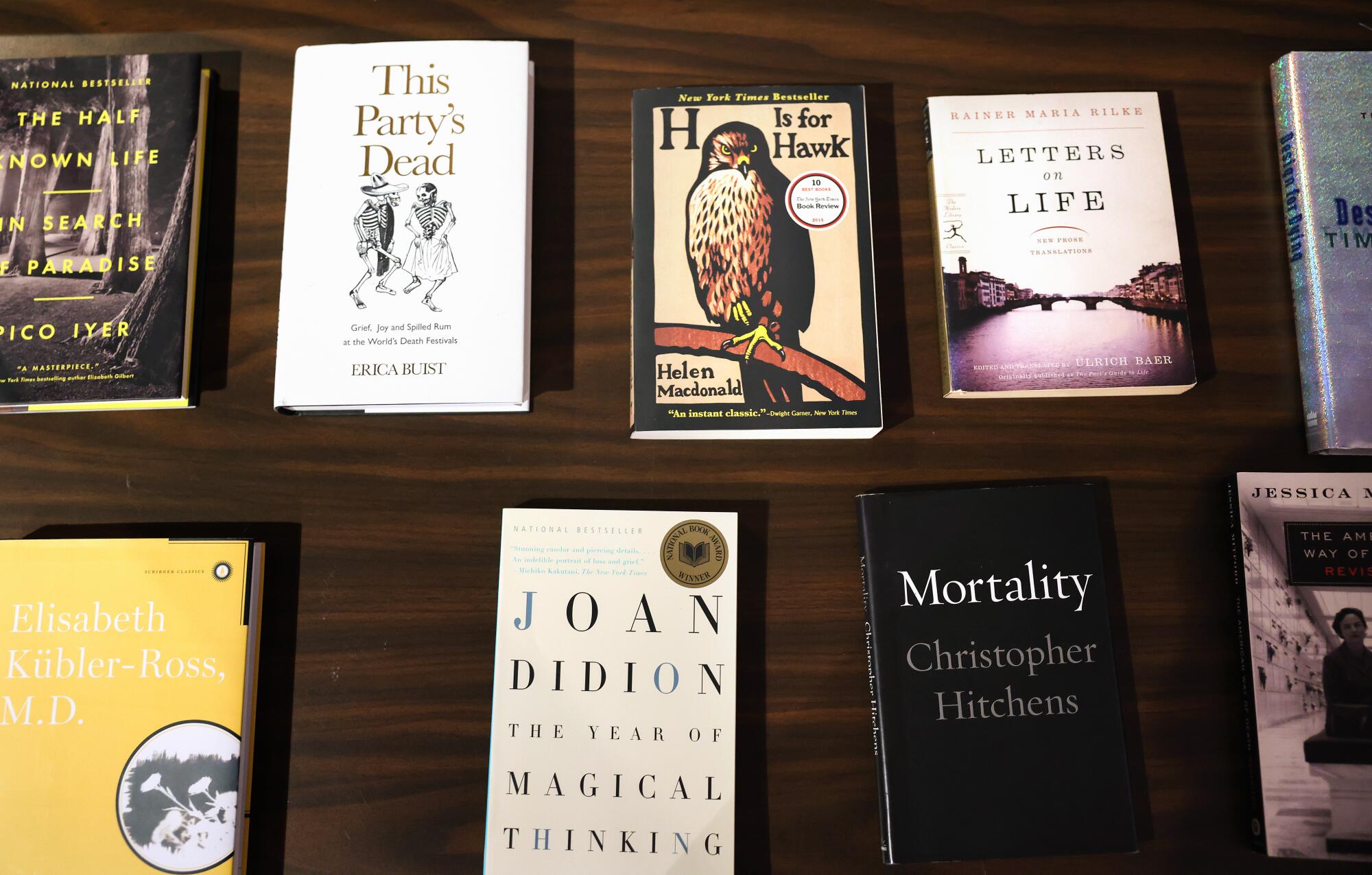

Reading material suggested by Elizabeth Lui, who hosted a death cafe at the Philosophical Research Society.

“The tradition in Southern California has long been about the journey. Making the most of the journey creatively, playfully, intellectually,” Lui tells me in the Philosophical Research Society’s regal library. “That’s what I also like about the death cafe. It has this edge of humor to it. If you’re at a dinner party and it’s boring, you can just say, ‘Have I told you about the death cafe I go to?’ and everybody just laughs. It’s such a great entree to the conversation.”

Lui’s twice-monthly gathering is one of several death cafes that have sprung up over the past two years in Los Angeles. Heavy Manners Library, an art space and lending library specializing in independent books and zines, holds one every other month. Its organizer, Emily Yacina, has made a habit of bringing donuts for the mostly 20- and-30-something tattooed crowd. Artist Ailene deVries held a death cafe in April at Gorky, an Eastside feminist collective that hosts workshops and pop-up events. North Figueroa Bookshop in Highland Park announced its first death cafe last summer, led by death doula Hazel Angell. A collaged flier for the meeting showed a skeleton hand clutching a butterfly above a succinct description written in gothic font: “A group discussion of death with no agenda, objectives or themes.”

The agenda-less ethos of the death cafe was developed in 2011 by Jon Underwood. The then 38-year-old Buddhist student and former government worker is widely credited for hosting the first modern death cafe at his home in East London. He was inspired to organize it after reading about Swiss “cafe mortels,” gatherings designed by the late sociologist Bernard Crettaz in 2004 to break the stigma around talking about death.

Underwood died unexpectedly in 2017 due to complications from leukemia, but the movement he kickstarted remains very much alive. A website maintained by Underwood’s mother and sister includes a how-to guide for those looking to start their own death cafe, and a directory that lists more than 18,000 death cafes around the world.

Greg Golden, 73, center, shares his experience beside fellow death cafe participants Danielle Tyas, 23, left, and Haley Twist, 32, right, at the Philosophical Research Society.

Megan Mooney, a clinical and medical social worker who serves as a volunteer spokesperson for Underwood’s umbrella organization, says she’s seen an increase in death cafe listings since 2020.

“COVID really made people have to face their own mortality,” she said in a Facebook message. “There was no escaping it …There was a huge demand for people wanting to talk about death for the first time.”

That was certainly true for Lui, who says the “pervasiveness of death” during the first couple years of the pandemic led her to get certified as an end-of-life doula in March 2022.

“I really was alarmed by the fact that we couldn’t form a consensus on how to deal with the pandemic and deal with the widespread phenomenon of this many deaths,” she said. “I don’t think the seriousness of it was something that we were even able to grasp because we avoid this topic at all costs.”

Though Lui’s death cafe may be the most frequently held one in Los Angeles, it’s not the county’s first. Hospice social worker Betsy Trapasso claims that distinction, after having launched a death cafe from her home in Topanga Canyon in 2013.

“It’s not a support group. It’s not a grief group,” Trapasso told The Times that year. “My whole thing is to get people talking about [death] so they’re not afraid when the time comes.”

During the event, Trapasso asked the group of aging professionals to inhale some lavender oil to relax at the start of the session. (Though she no longer hosts a death cafe, she maintains a Facebook page where she posts articles and events related to aging, grief and end-of-life care.)

Participants sit in a circle at the death cafe.

More than a decade later, there are no bongos or essential oils at L.A.’s latest wave of death cafes and, most noticeably, their attendees skew younger. At the Thursday and Saturday sessions I attended at the Philosophical Research Society, most people were in their 20s, 30s and early 40s. At Heavy Manners Library on a Tuesday night, the group would not have looked out of place at a music show at the Echoplex down the street.

Lui sees the attendance of the millennials and zoomers at her death cafes as evidence of an unfortunate reality: that younger generations are experiencing the loss of loved ones. Some of them have cited suicide, alcoholism and drug overdoses as the cause.

“Young people are being exposed to friends dying, and more often than I think people realize,” she said.

Yacina, who leads the death cafe at Heavy Manners Library, is one of them. The 28-year-old indie rock musician says a good friend of hers died during her sophomore year of college, and she found the experience isolating, profound and “identity-forming.” Then, in 2021, she mourned the death of yet another friend, whom she later wrote a song about. Yacina said she realized “there’s no escape to people dying, and in fact, it’s actually the one true thing that we all can count on.” It led her to wonder: “Why don’t we talk about it more?”

Upcoming L.A. death cafes

She organized the Echo Park death cafe in June 2022, just a few months before Lui started one in Los Feliz. Like Lui, Yacina had recently gotten certified as an end-of-life doula, and the pandemic had planted the idea of death more firmly in her consciousness. In a phone interview, she recalled worrying that she could lose her parents to COVID-19.

“It was such a scary feeling, but the truth is, you could lose anyone at any time,” she said.

It’s a truth that deVries, the 27-year-old artist who recently held a death cafe at Gorky and plans to hold another in Long Beach this summer, had to learn the hard way.

“When I was 18, my partner just suddenly passed in a very traumatic way, so I wasn’t really sure where to put the conversation,” she said. “I think the death cafe was the first time that I felt I had a container to express my interest.”

Reading material suggested by Elizabeth Lui.

Sara Alessandrini, 35, listens closely as another participant shares during the death cafe.

Not everyone who attends these events has experienced a death in their family or community. Some attendees instead see death as a potent metaphor for life’s big changes and all the grief that comes along with them.

“It also helped me with living life in the moment and letting go of certain things,” said Sara Alessandrini, a 35-year-old filmmaker who attends Lui’s death cafe at the Philosophical Research Society.

When it’s her turn to share her reason for coming to the Thursday afternoon group, Alessandrini announces to the group that she wants to reflect not on the death of a person, but of her childhood. She talks about boundaries and healing. It prompts others to chime in, openly sharing stories about their upbringings. When the conversation comes to a pause, Lui offers some warm advice to Alessandrini: “I think you need to protect yourself even better than you think you’re protecting yourself.”

Lui often takes on a maternal role in the group. During one of my visits, she asks for an attendee’s phone number so she can text them a message of support on a day they say they’re dreading. At a separate session, she gets up from her chair to console someone in emotional distress. After the meetings, she emails death-themed book and movie recommendations to newcomers, who often comprise the majority of attendees. Timothy Leary’s “Design for Dying,” the Oscar-winning Japanese drama “Departures,” and the Sundance-winning documentary “How to Die in Oregon,” are all on her list.

Since many of her attendees are artists themselves, she sends out invites to their events, which often intersect with ideas about death. Recent examples include an online radio program featuring songs for funerals and a solo show about grief debuting at the Hollywood Fringe festival this month.

Lui sometimes signs her emails: “Hope to see you when it fits.” She wants attendees to know there’s no obligation to return to her death cafe. Even still, the group can sometimes get large and unwieldy. At one recent death cafe, Lui recalled, there were 30 people, “and that was a little too much.”

Michael Allison, 62, laughs a little while sharing with the group of participants in the death cafe.

The death cafe can sometimes feel like group therapy. But Lui makes no claims of being a therapist. “I think in a good way, we’re not therapists,” she told me. “Because we’re not just nodding and listening and letting them figure out their own truth. We actually have some ideas about where you find meaning in your life.”

At the Thursday afternoon death cafe at the Philosophical Research Society, everyone has so much to say that the conversation stretches for hours. Toward the end, it becomes loose and playful, resembling a late-night heart-to-heart. Between bouts of tears and laughter, someone asks: Do you think you know that you’re dead after you’ve died? Another poses a question: Is it just me, or has anyone else ever wondered if your dead parent can see you when you’re having sex? The room giggles, and it reminds one attendee to share her own story about her deceased mother.

At some point, Lui asks whether anyone knows the time. It’s 6 p.m. — meaning the death cafe has stretched on for four hours, twice as long as scheduled. Lui frantically apologizes, but nobody seems to mind. They hang around, talking and eating cupcakes.

“Maybe we need a weekend retreat or something?” Lui suggests. But even a few days wouldn’t be enough to contain everyone’s questions about one of life’s greatest mysteries. For now, her cafe will have to suffice.

Lifestyle

'We Are Lady Parts' rocks with bracing honesty and nuance : Pop Culture Happy Hour

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoNewson, Dem leaders try to negotiate Prop 47 reform off California ballots, as GOP wants to let voters decide

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoDozens killed near Sudan’s capital as UN warns of soaring displacement

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoWould President Biden’s asylum restrictions work? It’s a short-term fix, analysts say

-

World1 week ago

World1 week ago‘Bloody policies’: Bodies of 11 refugees and migrants recovered off Libya

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoEmbattled Biden border order loaded with loopholes 'to drive a truck through': critics

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoRead Justice Clarence Thomas’s Financial Disclosures for 2023

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoGun group vows to 'defend' Trump's concealed carry license after conviction

-

Politics7 days ago

Politics7 days agoShould Trump have confidence in his lawyers? Legal experts weigh in