Business

The 2024 box office is terrible. But Imax's big-screen appeal is a bright spot

When Warner Bros. film executive Jeff Goldstein saw the huge sand dunes and expansive desert vistas of Denis Villeneuve’s first “Dune” movie, he thought to himself, “This was made for Imax.”

Same went for the sandworm sequences of the sequel, “Dune: Part Two,” a box office hit for the studio earlier this year that pulled in nearly 24% of its domestic box office revenue from Imax. The dystopian wasteland of this weekend’s big action tent pole, “Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga,” brings yet more fodder for the big screen format.

Imax’s giant screens are expected to account for a greater-than-typical share of the George Miller-directed prequel’s box office sales. (The film is tracking to gross more than $40 million domestically for the four-day weekend opening, according to analysts.)

“It immerses you, so you’re there,” said Goldstein, president of domestic distribution for Warner Bros. Pictures. “Audiences look at Imax as something special.”

As studios and exhibitors bemoan audiences’ slow return to movie theaters since the pandemic, Imax has been one of the few bright spots. This year’s box office is down 20% compared to last year, when pictures like “Fast X,” “Barbie” and “The Super Mario Bros. Movie” propelled ticket sales, and yet studios are clamoring to get onto Imax screens.

Audience behavior has now changed, and getting people out of their houses and back into theaters requires something special they can’t get at home. That put Imax in a fortuitous spot.

The 57-year-old Canadian company, which operates out of Playa Vista, is coming off one of its best years, with Christopher Nolan’s “Oppenheimer” helping to fuel overall global box office revenue — marking Imax’s second-highest grossing year in its history. Films shown on Imax are reaping bigger box office numbers, helped in part by higher ticket prices, and that’s a powerful allure for studios and filmmakers.

Next year, 13 Hollywood movies slated for release will be shot on Imax digital cameras or film, beating a previous record logged in 2021 when seven so-called filmed for Imax movies came out.

The company hopes its brand awareness eventually looms so large that viewers come to its screens first.

“Instead of saying, ‘What’s happening at the movies?,’ I want them to say, ‘What’s happening at Imax?’” said Imax Corp. Chief Executive Rich Gelfond.

For Imax’s part, its financial performance in the first fiscal quarter of 2024 beat expectations. The company’s net income totaled $3.3 million for the three-month period that ended March 31, up 33% from the previous year, though revenue decreased by about 9%, to $79.1 million. Shares of Imax are up about 10.9% so far this year.

“While there are exceptions like ‘Barbie,’ it is very, very difficult to be a blockbuster without being in Imax,” said Greg Foster, a former Imax Entertainment chief executive who now runs an entertainment consulting business.

Imax’s current mainstream success is what Gelfond and his business partners envisioned when they acquired the company in 1994. At the time, Imax was essentially a museum staple, albeit one that allowed viewers to immerse themselves in the latest nature film or science documentary.

The company adjusted its screens and sound systems to fit in commercial multiplex theaters, allowing its business to grow rapidly while limiting costs (Imax does not own theaters itself, but instead supplies its screening technology to cinema chains). Imax also developed technology to convert movies to Imax’s format to make it more economically attractive for filmmakers and benefited from the advent of digital film, which made it more cost effective.

By 2019, the company had seen year-over-year global box office growth for several years and expanded its global market share to spread its box office almost evenly among North America, China and the rest of the world.

Like its movie theater owner customers, Imax was hit hard by COVID-19 business shutdowns. But because the company has few assets and little debt, it was insulated in part from the financial fallout that the rest of the industry faced. The company used the time to update its technology, including a new laser projection system and sound system, worked on its marketing and leaned more into local language films, Gelfond said.

Now in a post-pandemic world, moviegoers want something premium and special for their time, and they’re willing to pay for it. That’s a bonus for Imax and so-called premium large-format screens operated by the theater chains.

“In an industry that is constantly re-evaluating its present and its future in terms of competing with new media and bringing back audiences, it’s Imax that has been at the heart of the conversation when we talk about sectors of the industry that have recovered,” said Shawn Robbins, founder of analysis site Box Office Theory. “It’s been a way for studios to have reliability in an often volatile theatrical market.”

Walt Disney Co. has leaned hard into Imax and other premium large formats.

Its marketing campaign for “Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes,” released earlier this month, prominently featured the Imax logo on billboards, bus stop signs and other advertisements. During opening weekend, 41% of the movie’s domestic box office came from premium large-format screenings, 13% of which was Imax, Disney said. Typically, a blockbuster that hasn’t been filmed on Imax cameras, like “Apes,” would do about 10% at the box office, Gelfond said.

As an industry, “we need to give audiences a terrific experience every time they go to see a movie,” said Tony Chambers, executive vice president and head of theatrical distribution for Walt Disney Studios. “Going to see a movie in premium large formats helps drive engagement and helps drive frequency.”

From 2022 to 2023, premium large formats made up 19% of Disney’s total domestic business; just before the pandemic, that total was 15%. Some of that came from 3-D screens, which have tapered off in popularity.

The company saw box office success with James Cameron’s 2022 sequel, “Avatar: The Way of Water,” which brought in $1.6 billion in revenue from premium large formats out of a total of $2.32 billion (About 11% of which came from Imax). Marvel’s “Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3” last year brought in 31% of its box office revenue from premium large formats.

Especially since the pandemic, there’s now more competition for people’s time and attention from streaming and social media, making it crucial for studios to give audiences a good reason to leave their couches.

“We need a way to cut through some of the clutter and make it clear to people that you cannot wait, you need to see this on the big screen,” Chambers said. “One of the ways to do that, from a marketing perspective, is to lean heavily into the premium large format.”

For a lot of people, he said, that means Imax. In fact, Imax executives bristle when people lump them with the other so-called PLFs, which include Dolby Cinema and ScreenX.

Imax box office makes up 13% of Warner Bros. overall domestic business, compared to an industry wide 5% to 7%, according to the studio. Industry wide, opening weekends are typically 10% to 12% Imax. But some are a bigger draw. The Imax share of “Dune: Part Two’s” domestic box office was 22%.

“It’s this whole notion of how do you hit critical mass,” Goldstein said. “Imax will help you get to critical mass faster.”

Imax’s future hinges on continued growth, especially internationally. As of 2023, the company had 1,772 screens across the globe, including its institutional theaters and museum screens, up slightly from the previous year.

The company also plans to expand, particularly into markets that it thinks are under-served, such as Australia and Japan.

“It has massive growth potential globally, and it’s certainly not at saturation in most of its global markets at this point,” said Alicia Reese, media and entertainment analyst at Wedbush Securities. “They should trade at a higher multiple given their growth potential.”

Business

After 57 years of open seating, is Southwest changing its brand?

Jim Kingsley of Orange County, who recently flew Southwest on a two-leg journey from Minneapolis to Los Angeles, likened the budget-friendly airline to In-N-Out Burger.

Both brands are affordable, consistent and more simplistic compared with competitors, Kingsley said.

“They’re not trying to offer all the things everybody else offers,” he said, “but they get the quality right and it’s a good value.”

Change, however, is in the air.

Southwest, which since its founding nearly 60 years ago has positioned itself in the cutthroat airline industry as an easygoing, egalitarian option, upended that guiding ethos this week with word that it would get rid of its famous first-come, first-seated policy in favor of traditional assigned seats and a premium class option. They will also offer overnight, red-eye flights in five markets including Los Angeles.

Experts say the changes, especially the switch to assigned seating, are a smart move and will appeal to many as the company tries to stabilize its precarious finances that included a 46% drop in profits in the second quarter from a year earlier to $367 million. But it remains to be seen whether Southwest will pay an intangible cost in making the moves: Will it be able to hold on to its quirky identity or will it put off loyal customers, and in doing so, become just another airline?

“You’re going to hear nostalgia about this, but I think it’s very logical and probably something the company should have done years ago,” said Duane Pfennigwerth, a global airlines analyst at Evercore.

“In many markets away from core Southwest markets, we think open seating is a boarding process that many people avoid,” he said.

That is all well and good, but “I didn’t ask for these changes,” Kingsley said. “Cost and quality is what I care about.”

Open seating has its pros and cons, Kingsley said, though he’s generally a fan. On his trip to Los Angeles, his group wasn’t able to get seats all together. But he likes that preferred seats are available on a first-come, first-served basis, instead of being offered for a high price.

Eighty percent of Southwest customers and 86% of potential customers prefer an assigned seat, the airline said in a statement.

“By moving to an assigned seating model, Southwest expects to broaden its appeal and attract more flying from its current and future customers,” the airline said.

An even bigger draw of Southwest, according to Kingsley, is its policy of including two free checked bags per ticket. This perk often makes Southwest a better bargain, especially for longer trips or bigger groups, he said.

The free bags are a big deal to customers, experts said, and contribute to the airline’s consumer-friendly brand. The airline hasn’t indicated they plan to change their bag policy.

“Southwest has always had a really good, positive vibe,” said Alan Fyall, chair of Tourism Marketing at the University of Central Florida’s College of Hospitality. “It’s free bags, good prices and point-to-point routes. That’s what they stand for and that’s what people love about them.”

Southwest’s change to assigned seating doesn’t mean they’re no longer a budget-friendly airline, Fyall said, but it does differentiate them from the lowest-cost, lowest-amenity options such as Frontier and Spirit.

The move will also require Southwest to update all or a portion of its fleet to include first-class seats. Currently, all seats on a Southwest flight are identical. Fyall said it’s worth the investment.

It’s an appropriate time for Southwest to make adjustments, said Chris Hydock, an assistant professor at Tulane University’s Freeman School of Business.

“They’ve not been profitable the last couple of quarters and they’ve had some activist investor pressure to increase their revenue,” he said.

Costs such as wages and maintenance have risen across the airline industry even as travel increased after the pandemic. Southwest saw a net loss of $231 million in the first quarter of 2024. Wall Street analysts estimate that assigned, premium seating could boost revenue by $2 billion per year.

“This is one of the options where they could potentially increase their revenue and do something that a lot of consumers have a strong preference for anyway,” Hydock said.

For Southwest’s changes to pay off, it has to stick to its roots when it comes to its culture and brand, experts and travelers agreed.

“I love Southwest being different,” Kingsley said. “If they’re trying to be like the other airlines, I think they’re shooting themselves in the foot.”

Business

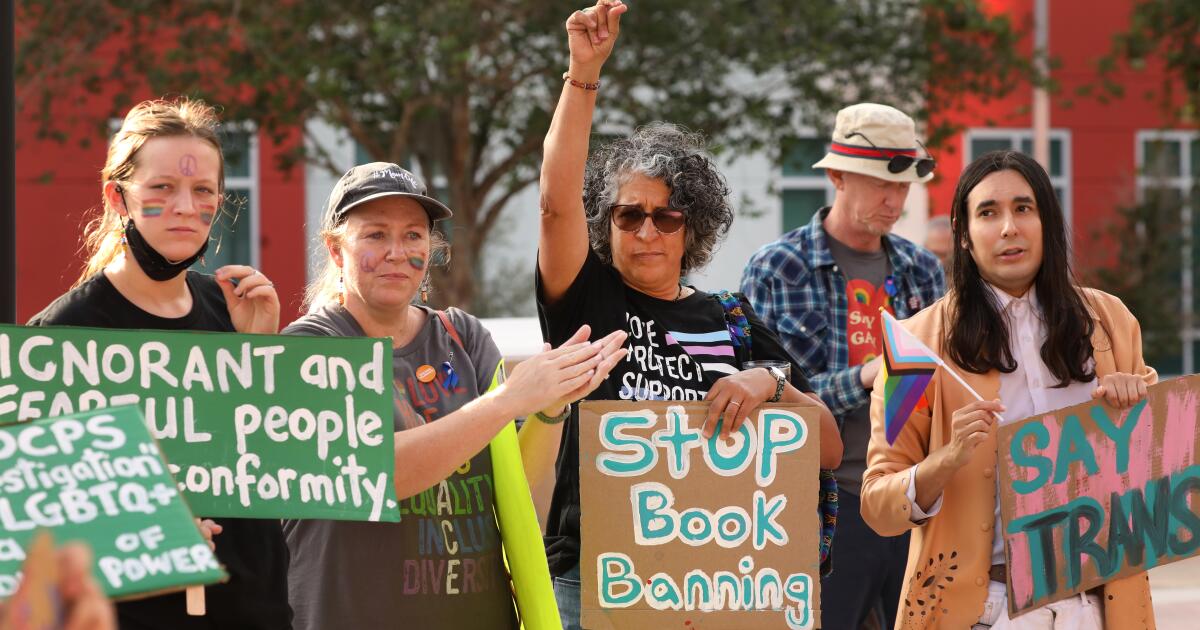

Column: 99 years after the Scopes 'monkey trial,' religious fundamentalism still infects our schools

Almost a century has passed since a Tennessee schoolteacher was found guilty of teaching evolution to his students. We’ve come a long way since that happened on July 21, 1925. Haven’t we?

No, not really.

The Christian fundamentalism that begat the state law that John Scopes violated has not gone away. It regularly resurfaces in American politics, including today, when efforts to ban or dilute the teaching of evolution and other scientific concepts are part and parcel of a nationwide book-banning campaign, augmented by an effort to whitewash the teaching of American history.

I knew that education was in danger from the source that has always hampered it—religious fanaticism.

— Clarence Darrow, on why he took on the defense of John Scopes at the ‘monkey trial’

The trial in Dayton, Tenn., that supposedly placed evolution in the dock is seen as a touchstone of the recurrent battle between science and revelation. It is and it isn’t. But the battle is very real.

Let’s take a look.

The Scopes trial was one of the first, if not the very first, to be dubbed “the trial of the century.”

And why not? It pitted the fundamentalist William Jennings Bryan — three-time Democratic presidential candidate, former congressman and secretary of State, once labeled “the great commoner” for his faith in the judgment of ordinary people, but at 65 showing the effects of age — against Clarence Darrow, the most storied defense counsel of his time.

The case has retained its hold on the popular imagination chiefly thanks to “Inherit the Wind,” an inescapably dramatic reconstruction — actually a caricature — of the trial that premiered in 1955, when the play was written as a hooded critique of McCarthyism.

Most people probably know it from the 1960 film version, which starred Frederic March, Spencer Tracy and Gene Kelly as the characters meant to portray Bryan, Darrow and H.L. Mencken, the acerbic Baltimore newspaperman whose coverage of the trial is a genuine landmark of American journalism.

What all this means is that the actual case has become encrusted by myth over the ensuing decades.

One persistent myth is that the anti-evolution law and the trial arose from a focused groundswell of religious fanaticism in Tennessee. In fact, they could be said to have occurred — to repurpose a phrase usually employed to describe how Britain acquired her empire — in “a fit of absence of mind.”

The Legislature passed the measure idly as a meaningless gift to its drafter, John W. Butler, a lay preacher who hadn’t passed any other bill. (The bill “did not amount to a row of pins; let him have it,” a legislator commented, according to Ray Ginger’s definitive 1958 book about the case, “Six Days or Forever?”)

No one bothered to organize an opposition. There was no legislative debate. The lawmakers assumed that Gov. Austin Peay would simply veto the bill. The president of the University of Tennessee disdained it, but kept mum because he didn’t want the issue to complicate a plan for university funding then before the Legislature.

Peay signed the bill, asserting that it was an innocuous law that wouldn’t interfere with anything being taught in the state’s schools. The law “probably … will never be applied,” he said. Bryan, who approved of the law as a symbolic statement of religious principle, had advised legislators to leave out any penalty for violation, lest it be declared unconstitutional.

The lawmakers, however, made it a misdemeanor punishable by a fine for any teacher in the public schools “to teach any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man had descended from a lower order of animal.”

Scopes’ arrest and trial proceeded in similarly desultory manner. Scopes, a school football coach and science teacher filling in for an ailing biology teacher, assigned the students to read a textbook that included evolution. He wasn’t a local and didn’t intend to set down roots in Dayton, but his parents were socialists and agnostics, so when a local group sought to bring a test case, he agreed to be the defendant.

The play and movie of “Inherit the Wind” portray the townspeople as religious fanatics, except for a couple of courageous individuals. In fact, they were models of tolerance. Even Mencken, who came to Dayton expecting to find a squalid backwater, instead discovered “a country town full of charm and even beauty.”

Dayton’s civic boosters paid little attention to the profound issues ostensibly at play in the courthouse; they saw the trial as a sort of economic development project, a tool for attracting new residents and businesses to compete with the big city nearby, Chattanooga. They couldn’t have been happier when Bryan signed on as the chief prosecutor and a local group solicited Darrow for the defense.

“I knew that education was in danger from the source that has always hampered it — religious fanaticism,” Darrow wrote in his autobiography. “My only object was to focus the attention of the country on the programme of Mr. Bryan and the other fundamentalists in America.” He wasn’t blind to how the case was being presented in the press: “As a farce instead of a tragedy.” But he judged the press publicity to be priceless.

The press and and the local establishment had diametrically opposed visions of what the trial was about. The former saw it as a fight to protect from rubes the theory of evolution, specifically that humans descended from lower orders of primate, hence the enduring nickname of the “monkey trial.” For the judge and jury, it was about a defendant’s violation of a law written in plain English.

The trial’s elevated position in American culture derives from two sources: Mencken’s coverage for the Baltimore Sun, and “Inherit the Wind.” Notwithstanding his praise for Dayton’s “charm,” Mencken scorned its residents as “yokels,” “morons” and “ignoramuses,” trapped by their “simian imbecility” into swallowing Bryan’s “theologic bilge.”

The play and movie turned a couple of courtroom exchanges into moments of high drama, notably Darrow’s calling Bryan to the witness stand to testify to the truth of the Bible, and Bryan’s humiliation at his hands.

In truth, that exchange was a late-innings sideshow of no significance to the case. Scopes was plainly guilty of violating the law and his conviction preordained. But it was overturned on a technicality (the judge had fined him $100, more than was authorized by state law), leaving nothing for the pro-evolution camp to bring to an appellate court. The whole thing fizzled away.

The idea that despite Scopes’ conviction, the trial was a defeat for fundamentalism, lived on. Scopes was one of its adherents. “I believe that the Dayton trial marked the beginning of the decline of fundamentalism,” he said in a 1965 interview. “I feel that restrictive legislation on academic freedom is forever a thing of the past, … that the Dayton trial had some part in bringing to birth this new era.”

That was untrue then, or now. When the late biologist and science historian Stephen Jay Gould quoted that interview in a 1981 essay, fundamentalist politics were again on the rise. Gould observed that Jerry Falwell had taken up the mountebank’s mission of William Jennings Bryan.

It was harder then to exclude evolution from the class curriculum entirely, Gould wrote, but its enemies had turned to demanding “‘equal time’ for evolution and for old-time religion masquerading under the self-contradictory title of ‘scientific creationism.’”

For the evangelical right, Gould noted, “creationism is a mere stalking horse … in a political program that would ban abortion, erase the political and social gains of women … and reinstitute all the jingoism and distrust of learning that prepares a nation for demagoguery.”

And here we are again. Measures banning the teaching of evolution outright have not lately been passed or introduced at the state level. But those that advocate teaching the “strengths and weaknesses” of scientific hypotheses are common — language that seems innocuous, but that educators know opens the door to undermining pupils’ understanding of science.

In some red states, legislators have tried to bootstrap regulations aimed at narrowing scientific teaching onto laws suppressing discussions of race and gender in the classrooms and stripping books touching those topics from school libraries and public libraries.

The most ringing rejection of creationism as a public school topic was sounded in 2005 by a federal judge in Pennsylvania, who ruled that “intelligent design” — creationism by another name — “cannot uncouple itself from its creationist, and thus religious, antecedents” and therefore is unconstitutional as a topic in public schools. Yet only last year, a bill to allow “intelligent design” to be taught in the state’s public schools was overwhelmingly passed by the state Senate. (It died in a House committee.)

Oklahoma’s reactionary state superintendent of education, Ryan Walters, recently mandated that the Bible should be taught in all K-12 schools, and that a physical copy be present in every classroom, along with the Ten Commandments, the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. “These documents are mandatory for the holistic education of students in Oklahoma,” he ordered.

It’s clear that these sorts of policies are broadly unpopular across much of the nation: In last year’s state and local elections, ibook-banners and other candidates preaching a distorted vision of “parents’ rights” to undermine educational standards were soundly defeated.

That doesn’t seem to matter to the culture warriors who have expanded their attacks on race and gender teaching to science itself. They’re playing a long game. They conceal their intentions with vague language in laws that force teachers to question whether something they say in class will bring prosecutors to the schoolhouse door.

Gould detected the subtext of these campaigns. So did Mencken, who had Bryan’s number. Crushed by his losses in three presidential campaigns in 1896, 1900 and 1908, Mencken wrote, Bryan had launched a new campaign of cheap religiosity.

“This old buzzard,” Mencken wrote, “having failed to raise the mob against its rulers, now prepares to raise it against its teachers.” Bryan understood instinctively that the way to turn American society from a democracy to a theocracy was to start by destroying its schools. His heirs, right up to the present day, know it too.

Business

NASA identifies Starliner problems but sets no date for astronauts' return to Earth

After weeks of testing, NASA and Boeing officials said Thursday they have identified problems with the Starliner’s propulsion system that have kept two astronauts at the International Space Station for seven weeks — but they didn’t set a date to return them to Earth.

Ground testing conducted on thrusters that maneuver Boeing’s capsule in space found that Teflon used to control the flow of rocket propellant eroded under high heat conditions, while different seals that control helium gas showed bulging, they said.

The testing was conducted after the thrusters malfunctioned when Starliner docked with the space station on June 6 and a helium leak that was detected before launch worsened on the trip to the station. The helium pressurizes the propulsion system.

However, officials said the problems should not prevent astronauts Suni Williams and Butch Wilmore from returning to Earth aboard the Starliner capsule, which lifted off on its maiden human test flight June 5 for what was supposed to be an eight-day mission.

“I am very confident we have a good vehicle to bring the crew back with,” Mark Nappi, program manager of Boeing’s Commercial Crew Program, said at a news conference.

NASA and Boeing officials have said previously that the Starliner could transport the astronauts to Earth if there were an emergency aboard the space station, but they opted to conduct the ground tests to ensure a safe, planned return.

Decisions on whether and when to use Starliner or another vehicle will be made by NASA leaders after they are presented next week with all the information collected from the testing, which will include a “hot fire” test of the engines of the Starliner docked at the space station, Nappi said.

Rigorous ground testing conducted at NASA’s White Sands Test Facility on a thruster identical to the ones on the Starliner found that, despite the issues with Teflon degradation, the thruster was able to perform the maneuvers that would be needed to return Starliner to Earth, said Steve Stich, program manager for NASA’s Commercial Crew Program.

Official also have said that the Starliner still has about 10 times more helium than is needed to bring the capsule back to Earth.

The problems that have cropped up have been an embarrassment for Boeing, which along with SpaceX was given a multibillion-dollar contract in 2014 to service the station with crew and cargo flights after the end of the space shuttle program. Since then, Elon Musk’s Hawthorne-based company has sent more than a half-dozen crews up, while Boeing is still in its testing phase — with the current flight delayed for weeks by the helium leak and other issues that arose even before the thrusters malfunctioned.

Should NASA make a decision not to bring the crew home on the Starliner — which could still return to Earth remotely — the astronauts could be retrieved by SpaceX’s Crew Dragon capsule, though SpaceX’s workhorse Falcon 9 rocket is currently grounded after a failure this month.

The Russian Soyuz spacecraft also services the station and carries American astronauts.

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoOne dead after car crashes into restaurant in Paris

-

Midwest1 week ago

Midwest1 week agoMichigan rep posts video response to Stephen Colbert's joke about his RNC speech: 'Touché'

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: Young Republicans on Why Their Party Isn’t Reaching Gen Z (And What They Can Do About It)

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoMovie Review: A new generation drives into the storm in rousing ‘Twisters’

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoIn Milwaukee, Black Voters Struggle to Find a Home With Either Party

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoFox News Politics: The Call is Coming from Inside the House

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: J.D. Vance Accepts Vice-Presidential Nomination

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoTrump to take RNC stage for first speech since assassination attempt