Business

Column: Courts finally move to end right-wing judge shopping, but the damage may already be done

Some lawsuits are won by smart lawyers and some on the facts. But nothing spells success as much as the ability to pick your own judge.

That’s the lesson taught by conservative activists who have moved in federal courts to overturn government programs and policies on abortion, contraception, immigration, gun control, student loan relief and vaccine mandates, among other issues.

In recent years they’ve gamed the judicial system to get their lawsuits heard by judges they knew would be sure to see things their way. The process is known as judge shopping, and the committee that makes policy for the federal courts just moved to put an end to it.

The courts have now formally recognized the need to do something about a really troubling pattern of judge shopping.

— Amanda Shanor, University of Pennsylvania constitutional law expert

In a policy statement and official guidance issued last week, the Judicial Conference of the United States said that henceforth, any lawsuit seeking a statewide or nationwide injunction against a government policy or action should be assigned at random to a judge in the federal district where it’s filed.

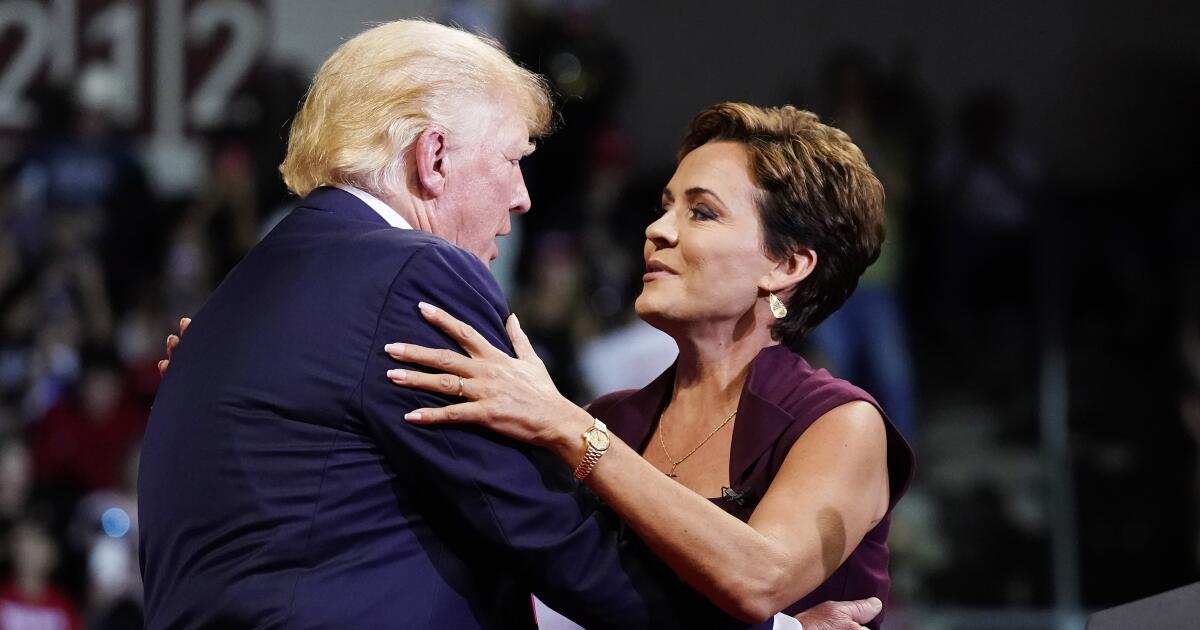

If that sounds a bit vague to the layperson, its target is crystal clear to legal experts: It’s aimed at right-wing activists and politicians who have filed their cases in federal courthouses presided over by highly partisan judges in Texas. Most of those judges were appointed by Donald Trump.

It would be bad enough if those judges’ rulings applied only within their judicial districts or affected only the plaintiffs. But the judges have issued sweeping nationwide injunctions that block government programs and policies coast-to-coast.

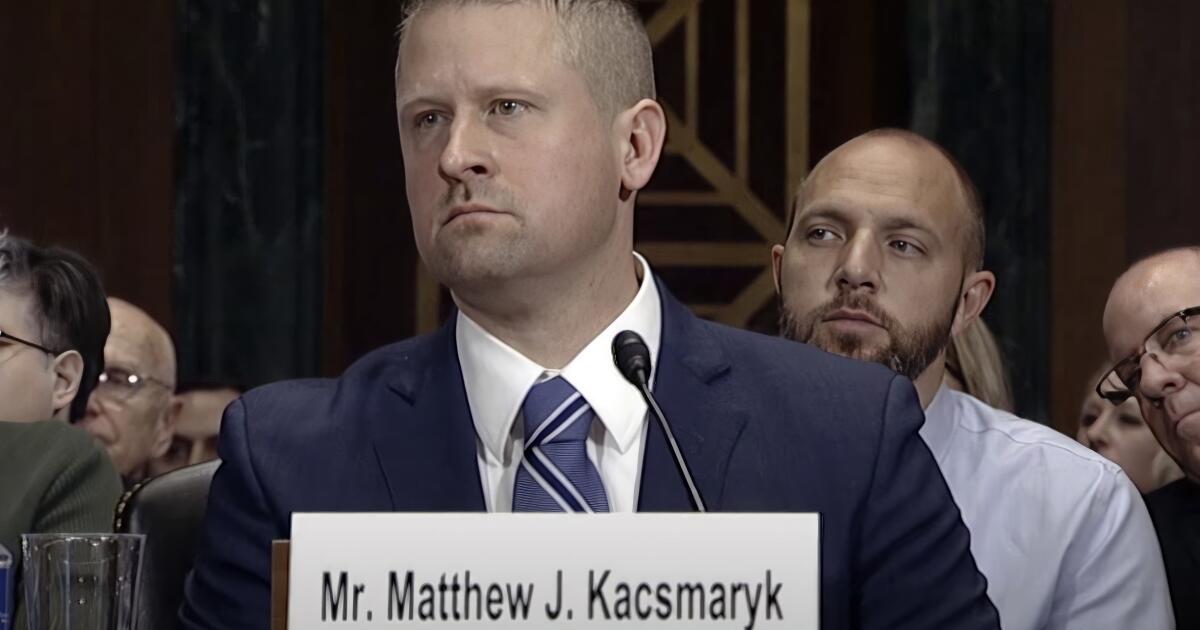

As Ian Millhiser of Vox put it, this is America’s “Matthew Kacsmaryk problem.” Kacsmaryk is the Trump-appointed Texas federal judge who most recently attempted to outlaw mifepristone, a widely used abortion medication, nationwide. His April 2023 ruling has been temporarily stayed by the Supreme Court, but it’s still on the docket, ticking away.

But Kacsmaryk is not alone. As recently as March 8, Judge J. Campbell Barker, a Trump appointee who presides over 50% of the civil cases filed in his rustic courthouse in Tyler, Texas, invalidated a ruling by the National Labor Relations Board broadening the standard by which big corporations could be held jointly responsible for the welfare and unionization rights of workers employed by their franchisees.

How serious a blow could the judicial conference’s policy be to conservatives aiming to roll back civil rights? Massive, judging from the reaction of Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.). Only 48 hours after the conference announced its initiative, McConnell wrote to the chief judges of all judicial districts urging them to ignore the new policy.

This was an audacious move, considering that the presiding officer of the Judicial Council is Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr., its membership comprises the chief judges of the 12 judicial circuits and one judge from a district court in each circuit, and its role is to set policy for the entire federal court system.

McConnell asserted that only Congress can make the rules for the assignment of federal trial judges, but that’s dubious. In an analysis last year, the Justice Department concluded that the Supreme Court has full authority to impose rules of civil procedure in the federal courts, including a rule mandating that all federal judicial districts assign judges randomly to civil lawsuits aimed at statewide or nationwide injunctions. The Judicial Council’s policy isn’t the same as as a Supreme Court rule, but it’s a fair bet that if pushed, the court would issue the rule.

McConnell also asserted that the Judicial Conference had been pressured into acting by Senate Majority Leader Charles E. Schumer (D-N.Y.), but that’s untrue. Although Schumer has spoken out against judge shopping, numerous legal experts and Roberts himself have expressed concerns about the practice.

“The courts have now formally recognized the need to do something about a really troubling pattern of judge shopping,” Amanda Shanor, a constitutional law expert at the University of Pennsylvania, said of the Judicial Conference’s initiative.

What’s yet unclear is whether the conference’s initiative goes far enough. Its policy statement is described as “guidance,” not a mandate. it acknowledges the district courts’ “authority and discretion” to manage their dockets as they see fit.

Last year, Shanor, with Alice Clapman and Jennifer Ahearn of NYU’s Brennan Center for Justice, proposed that the conference require all judicial districts to use a “random or blind procedure” to distribute cases among all the judges in the district when the litigants seek an injunction or other relief that would extend beyond the district’s borders.

The practice traditionally labeled “forum shopping” is not especially new. The earliest case cited by legal experts dates back to 1842, when a litigant chose to file a lawsuit in federal rather than state court in New York to gain a strategic advantage over his adversary.

Plaintiffs have been known to choose a venue based on local statutes of limitation, or a sense that juries in a region might be more amenable to their case, or because their location may be more convenient for parties or witnesses.

More recently, however, the practice has been heavily abused for partisan and ideological purposes. This results from two trends. One is the increasing partisanship of individual federal judges, especially those appointed by Trump. The second is those judges’ habit of issuing nationwide injunctions against government policies or programs.

Nationwide injunctions can impose parochial partisan ideologies on the whole country. Through 2023, the state of Texas filed more than 31 federal lawsuits challenging Biden administration policies — but not a single one in federal court in Austin, which is the state capital but an island of blue in a red state.

The state had filed seven lawsuits in Amarillo, where by local procedure every one was automatically assigned to Kacsmaryk; six in Victoria, where all civil cases are assigned to Trump appointee Drew B. Tipton; and four in Galveston, where all civil cases come before Trump appointee Jeff Brown.

The rest were filed in divisions with two judges, most of whom are also Trump appointees or conservative appointees of George W. Bush. In the Tyler division from which Barker issued his NLRB decision, all the cases he doesn’t get are assigned to Judge Jeremy Kernodle, also a Trump appointee.

Although some nationwide injunctions have been lifted by the Supreme Court, that process seldom happens speedily. The result is that the plaintiffs effectively win by losing, as injunctions against government policies can have “the lasting systemic effect of blocking these policies for months or years,” Shanor, Clapman and Ahearn observed.

Kacsmaryk got the mifepristone case for two reasons. First, antiabortion activists knew of his strong antiabortion inclinations. Second, the policy in the Northern District of Texas is to assign cases to judges in the division where they’re filed.

Kacsmaryk is the only judge sitting in the Amarillo division of the Northern District of Texas. So it was an easy call for the mifepristone plaintiffs to file there, knowing that their chance of drawing Kacsmaryk as their judge was 100%.

The same pattern drove plaintiffs to file lawsuits against Biden administration initiatives in the same district’s Fort Worth division, which has two judges, Trump appointee Mark T. Pittman and George W. Bush appointee Reed O’Connor. Both have been sought by conservative litigants. O’Connor also presides over 100% of the cases filed in the district’s Wichita Falls courthouse, where he is the only judge.

Pittman obligingly overturned Biden’s student loan relief program in 2022. Just this month, he ruled the government’s 55-year-old Minority Business Development Agency to be unconstitutional and ordered it opened to contract applicants of all races — obviously a ruling that defeats the purpose of a program designed to help minorities get a start in the business world. O’Connor tried to declare the entire Affordable Care Act unconstitutional in 2018. The Supreme Court overruled him in 2021.

The judicial conference’s initiative is long overdue.

Customarily, rulings by federal trial judges have constituted precedents binding at most on other judges in a particular judicial district or resulted in court orders benefiting only the plaintiffs who filed the case.

Matters are different “when a court effectively can bind the entire nation with an injunction” that applies to “an unlimited range of persons and to conduct occurring in … an equally unlimited array of places,” legal scholar Ronald A. Cass wrote in 2018.

The prospect of sweeping rulings incentivizes “an extreme race to courthouses more inclined to issue nationwide injunctions and more sympathetic to the plaintiff’s position,” Cass wrote.

In its latest incarnation, “litigants effectively have the ability to effectively choose an actual judge,” Shanor told me.

“We don’t know how the policy will be rolled out, what exactly is in it, or how much of it is a recommendation rather than a requirement,” she says. “A policy may be effective, but having a rule would advance the fairness and randomness of the distribution of these nationally important cases, and ensure the perceived legitimacy of the courts.”

One is that the policy won’t apply to cases that have already been assigned to a judge. Another is that litigants can still try to game the system by filing their lawsuits in states from which appeals are heard by circuit courts known to have a particular partisan lean.

That’s a major issue with Texas cases, which are funneled on appeal to the 5th Circuit, sitting in New Orleans. That court has been the source of right-wing decisions so loopy that they’ve been slapped down by the conservative majority on the Supreme Court. Of that circuit’s 17 active judges, six are Trump appointees.

McConnell’s objection to the Judicial Conference’s policy thus should be seen in context. He had more to do than anyone else with embedding Trumpian judges in the federal judiciary, where they wreak havoc on government policies and programs that help ordinary Americans, not just corporations and the rich. The conference’s initiative may be the first step toward a more fair-minded judiciary, but it’s a crucial one.

Business

Column: As taxpayers tire of handouts to billionaires, Major League Baseball demands public funding for a Vegas stadium

The longest-running melodrama in sports is less about events on the field of play than on machinations in the ownership suite of baseball’s Oakland A’s, who are close to finalizing a move to Las Vegas three or four years from now.

At least, that’s the hope of Major League Baseball and the team’s billionaire owner, John Fisher. That the deal will ultimately close as expected is the way to bet, to speak the language of Las Vegas.

But increasingly there are grounds to take the under. As my colleague Bill Shaikin reports, two challenges to the public funding for the team’s proposed new Vegas ballpark have emerged from a Nevada teachers union.

During the last Legislative Session, with important education issues outstanding,…Nevada politicians singularly focused on financing a ‘world-class’ stadium for a California billionaire.

— Nevada State Teachers Assn.

Strong Public Schools Nevada, a political action committee of the Nevada State Education Assn., has filed a lawsuit questioning the public funding as unconstitutional. A separate committee of the union is pressing to qualify for November’s state ballot a voter referendum on the funding.

At issue is a measure signed last year by Nevada’s Republican governor, Joe Lombardo, authorizing $380 million in public funding for a ballpark estimated to cost $1.5 billion. The rest supposedly would come from Fisher and any other private investors he persuades to come on board.

The absurdity of making a grant of public money to a billionaire and his rich cronies for a sports venue while other public needs are more pressing isn’t lost on the teachers, and it shouldn’t be lost on anyone else.

“Nevada ranks 48th in per pupil funding with the largest class sizes and highest educator vacancies in the nation,” the teachers union stated when it filed its lawsuit in February. Yet “during the last Legislative Session, with important education issues outstanding … Nevada politicians singularly focused on financing a ‘world-class’ stadium for a California billionaire.”

They’re right. Fisher, whose net worth is estimated by Forbes to be $3 billion, is the quintessential member of the Lucky Sperm Club, not to be indelicate. He’s an heir of Donald and Doris Fisher, founders of Gap Inc. Forbes ranks his “self-made score” at 2 on a scale of 10, meaning that almost all his wealth was inherited.

As I wrote last year, since becoming the sole owner of the A’s in 2016, Fisher has systematically dismantled the team and allowed its home stadium, the Oakland Coliseum, to crumble away.

The nearly 60-year-old multipurpose park was always a terrible place to watch a baseball game, with seats ridiculously distant from the action, but in recent years the experience has only gotten worse. During one game, the stadium flooded with sewage. On another occasion, the lights went out. Feral animals roamed the increasingly vacant corridors. Then, for the 2022 season, Fisher doubled season ticket prices.

Meanwhile, he and MLB commissioner Rob Manfred shed crocodile tears over the lack of fan support in Oakland. But what kind of product have Fisher and MLB been asking fans to pay for? In a nutshell: The A’s stink. Last year they turned in the worst record in baseball by losing 112 of their 162 games. They scored 339 fewer runs than they gave up to opponents.

This record was the product not of chance, but design. The team payroll last season of $43 million ranked dead last in the league, 12% of the league-leading New York Mets (who, to be fair, hardly made the most of their $334-million payroll, losing nearly 54% of their games). The best-paid player on the A’s, shortstop Aledmys Diaz, batted .229 last year and has started this season on the injured list.

Fisher embarked on an ostensibly serious search for an alternative venue in the Bay Area. Oakland municipal officials trying to work with him on a plan to keep the team accused him of sabotaging those efforts, in part by insisting on massive subsidies for expansive joint stadium/commercial/residential developments.

Oakland A’s owner John Fisher

(Michael Zagaris / Getty Images)

The A’s have announced that after completing their sojourn in Oakland at the end of the season, they’ll play in the ballpark of the minor league Sacramento River Cats for the next three years, maybe four, while their new stadium rises on the Vegas Strip site of the Tropicana Hotel, which is due to be demolished this year.

The Sacramento ballpark has about 14,000 seats, but it may still seem almost vacant when the A’s play there, as the average attendance at the team’s 13 home games in Oakland so far this year is 6,243, worst in the league by an unhealthy margin. The last year that average home attendance at A’s games exceeded 14,000 was 2019. At a game last May between the A’s and the Arizona Diamondbacks, only 2,064 seats were occupied, the lowest attendance for an A’s game in 44 years.

So what would Las Vegas gain from importing the A’s? Probably almost nothing. In very rare cases, a new sports venue can augment economic activity in a town or city, usually one with little else in sports or entertainment on offer.

Las Vegas is not exactly the kind of community in desperate need of another tourist draw. An A’s ballpark — or for that matter, the NFL Raiders’ Allegiant Stadium, where this year’s Super Bowl was held — can’t do much for a city where hotel occupancy is generally close to the highest in the nation.

As Bloomberg reported earlier this year apropos of Allegiant, “had the $1.9 billion stadium not been built at all, Las Vegas businesses wouldn’t have noticed the difference.” And any time that tourists spend at a ballgame is time they’re not spending inside the city’s true cash cows, its casinos.

Even when a new venue brings in new dollars, the gains for the home community typically comes at the expense of its larger region. Think of it as the Inglewood effect: This outpost of 110,000 residents may be seeing more business from SoFi Stadium, where the NFL Rams and Chargers play, but the chances that it has had a measurable impact on Los Angeles County (population 9.7 million) are minuscule to the point of being nonexistent.

Some Inglewood business owners and residents, as it happens, are complaining that the project has brought them increased traffic and noise; higher residential and commercial rents have forced some residents and businesses out of the city.

That brings us back to the challenges to the Vegas stadium financing brought by the Nevada teachers. The clock is ticking on both the union’s lawsuit and its proposed ballot measures. Since February, almost nothing has happened in the Carson City courthouse where the lawsuit was filed.

That makes the A’s nervous, for the legislative authorization for public financing expires 18 months after MLB’s approval of the team’s relocation, which was delivered on Nov. 16 with a unanimous vote of the MLB team owners — giving the team a deadline of mid-May 2025 to complete all its necessary agreements with local authorities. That places the deadline a bit more than a year from now, assuming the court allows the legislation to stand.

If the legislation is overturned, the team and its government promoters would be back at square one. That’s why the team petitioned the court a few days ago to allow it to intervene in the lawsuit, which would allow them to speak up for their own interests in court. “The Athletics … will be affected if SB 1 is found unconstitutional,” A’s President Dave Kaval declared in a court filing. “Each year of delay will cost the Athletics millions of dollars.”

The union’s effort to overturn the public financing at the ballot box is also moving slowly through the Nevada courts. Its petition to place a referendum on the November ballot was invalidated in November by a state judge. The union appealed to the Nevada Supreme Court, which heard oral arguments on the case April 9 but hasn’t issued a decision.

The union has until June 26, or just over two months from now, to collect more than 102,000 valid signatures of registered voters to place the referendum on the November ballot. But it can’t start the process until the court resolves the validity of its petition.

That’s important, because there are indications that Nevada voters are less than eager to spend public money on the A’s stadium. A poll released April 4 by the nonpartisan polling center of Boston-based Emerson College found that 52% of voters are opposed to the public funding, against only 32% in favor and 17% unsure.

The public financing of stadiums for team owners who could pay for construction out of their own pockets peaked in the 1990s, when voters finally got fed up with giveaways that left their cities and states holding the bag for venues that consistently ran in the red.

The trend faded, but never entirely disappeared. Recently, it has experienced a revival. Last year, the New York legislature and Erie County approved subsidies totaling at least $850 million for a new stadium for the NFL‘s Buffalo Bills. The team’s owner, oil and gas tycoon Terry Pegula, is even richer than Fisher, with a net worth of $6.8 billion, according to Forbes; he’s also almost entirely a self-made man.

Pegula brought the politicians to heel by threatening to move the team to Austin. The result was the largest taxpayer handout in U.S. sports history, narrowly edging out the $750-million subsidy Nevada posted to bring the NFL Oakland Raiders to Las Vegas in 2022.

The game of rent-seeking that Fisher has played with Oakland and Las Vegas is every bit as humiliating for taxpayers as the Bills and Raiders deals. It will make the A’s the most-traveled pro sports team in American history, having originated as the Philadelphia Athletics under the legendary Connie Mack in 1901 before moving to Kansas City in 1955 and Oakland in 1968, with Sacramento and Las Vegas now in its future.

So a sports franchise with 15 American League pennants and nine World Series titles to its name and more than 100 years of loyal fandom in three cities will continue its existence as a token of Major League Baseball’s unsavory dalliance with the gambling industry.

The supine political leaders of Nevada should be ashamed at sticking their constituents with a billionaire’s invoice. The lords of the MLB should be ashamed of so shabbily treating the fans who supported the Oakland A’s through four World Series titles and stuck with them until Fisher made the spectacle on the field simply unwatchable.

Here’s an easy prediction: This won’t be the last time that pro sports owners show their willingness to treat their fans like crap, as long as someone is off in the distance waving millions of dollars around.

Business

Amid homeowner insurance crisis, consumer advocates and industry clash at hearing

The fault lines running through California’s spiraling homeowners insurance crisis were on display Tuesday at a state hearing, where consumer advocates clashed with industry firms over a plan to allow insurers to use complex computer models to set premiums — a move state officials say will attract insurers to the market.

State Insurance Commissioner Ricardo Lara has proposed allowing insurers to employ so-called catastrophe modeling, which uses algorithms that predict the future risk properties face from wildfires, when setting the price of policies. Currently, rates are based on an insurance company’s past losses, which insurers increasingly dismiss as insufficient in light of the widespread acceptance that climate change has thrust California into a more dangerous future by causing more wildfires.

The models, which are in use in other states, are a key element of Lara’s strategy to moderate price increases by allowing more accurate calculation of risks while persuading insurers to do business in neighborhoods prone to wildfires. The move comes amid a recent stream of insurers exiting the California market with announcements they are not renewing policies or have stopped writing new ones.

Consumer groups worried at the hearing that the draft regulations would not allow enough scrutiny of the models, while several consulting firms that have developed them expressed concern about protecting their intellectual property.

“The algorithms and artificial intelligence that private ‘black box’ catastrophe models use will simply be tools for insurance company price gouging unless California mandates real transparency into how they impact prices and imposes real rules of the road regarding their design and use,” said Carmen Balber, executive director of Consumer Watchdog, an L.A. advocacy group that led the campaign for passage of Proposition 103, the 1988 measure that requires homeowners and auto insurers to get state approval for rate hikes.

The group, like other consumer advocates who spoke at the hearing, called on Lara to work with the state’s academic and insurance experts to develop a “public model,” in which all the factors that go into the computer simulations are available for everyone to review. Such a model could be used to set rates or benchmark privately developed models.

The draft regulations require those who want to review the models to sign nondisclosure agreements, which Consumer Watchdog has alleged will prevent its staff members from discussing the models among themselves.

Julia Borman, a director at Verisk, a company that builds computer models used by insurers, expressed concern that the draft proposal put forth by Lara would allow for a review by “countless participants and create the opportunity for an infinite timeline,” while not safeguarding companies from having their models ripped off by others

Michael Soller, the state Department of Insurance’s deputy commissioner for communications, said Lara has publicly stated that the draft rules will allow for the development of public catastrophe models, which the department might then use to evaluate the insurers’ proprietary models.

The proposal to allow catastrophe models is part of Lara’s larger Sustainable Insurance Strategy announced last fall. Other elements include righting the finances of the state’s Fair Access to Insurance Requirements plan, an insurer of last resort that has been deluged with new policyholders since insurers started pulling back from the market. He also wants to allow insurers to include in premiums the cost of reinsurance, which they purchase to protect themselves from disasters.

Catastrophe models are already allowed in California for pricing policies that cover earthquakes and fires caused by quakes. Along with wildfires, under the proposed regulations, the use of the models would also be permitted for insurance covering terrorism, floods and some other types of coverage.

Gerald Zimmerman, senior vice president of government and industry relations at Allstate, which stopped selling new homeowners insurance policies in the state in 2022, said that adopting Lara’s strategy would be a game changer. “Allstate will begin writing new homeowner insurance policies in nearly every corner of California,” he said.

Other speakers at the three-hour hearing included insurance agents and local officials, as well as homeowners groups, which want to ensure that catastrophe models take into account steps taken by homeowners and government agencies to reduce fire risks, such as by making homes more fire-resistant and reducing brush in a community. Although the draft regulations call for doing so, several speakers complained that such mitigation efforts had not been reflected in recent premium increases.

The Insurance Department plans to review Tuesday’s remarks in preparing for the release of a new set of proposed regulations. Lara has the support of Gov. Gavin Newsom, who issued a letter calling for the commissioner to move quickly to resolve the crisis. The regulations do not require legislative approval or the governor’s signature.

“We will review all public comments while staying on track to implement all changes this year, so insurance companies start writing more policies in all areas,” Soller said.

Business

Column: After a years-long pause, the FCC resurrects 'network neutrality,' a boon for consumers

In the midst of its battle to extinguish the Mendocino Complex wildfire in 2018, the Santa Clara County Fire Department discovered that its internet connection provider, Verizon, had throttled their data flow virtually down to zero, cutting off communications for firefighters in the field. One firefighter died in the blaze and four were injured.

Verizon refused to restore service until the fire department signed up for a new account that more than doubled its bill.

That episode has long been Exhibit A in favor of restoring the Federal Communications Commission’s authority to regulate broadband internet service, which the FCC abdicated in 2017, during the Trump administration.

This is an industry that requires a lot of scrutiny.

— Craig Aaron, Free Press, on the internet service industry

Now that era is over. On Thursday, the FCC — now operating with a Democratic majority — reclaimed its regulatory oversight of broadband via an order that passed on party lines, 3-2.

The commission’s action could scarcely be more timely.

“Four years ago,” FCC Chair Jessica Rosenworcel observed Thursday as the commission prepared to vote, “the pandemic changed life as we know it. … Much of work, school and healthcare migrated to the internet. … It became clear that no matter who you are or where you live, you need broadband to have a fair shot at digital age success. It went from ‘nice to have’ to ‘need to have.’ ”

Yet the commission in 2017 had thrown away its own ability to supervise this essential service. By categorizing broadband services as “information services,” it relinquished its right to address consumer complaints about crummy service, or even collect data on outages. It couldn’t prevent big internet service providers such as Comcast from favoring their own content or websites over competitors by degrading the rivals’ signals when they reached their subscribers’ homes.

“We fixed that today,” Rosenworcel said.

The issue the FCC addressed Thursday is most often viewed in the context of “network neutrality.” This core principle of the open internet means simply that internet service providers can’t discriminate among content providers trying to reach your home or business online — they can’t block websites or services, or degrade their signal, slow their traffic or, conversely, provide a better traffic lane for some rather than others.

The principle is important because their control of the information highways and byways gives ISPs tremendous power, especially if they control the last mile of access to end users, as do cable operators such as Comcast and telecommunications firms such as Verizon. If they use that power to favor their own content or content providers that pay them for a fast lane, it’s consumers who suffer.

Net neutrality has been a partisan football for more than two decades, or ever since high-speed broadband connections began to supplant dial-up modems.

In legal terms, the battle has been over the classification of broadband under the Communications Act of 1934 — as Title I “information services” or Title II “telecommunications.” The FCC has no jurisdiction over Title I services, but great authority over those classified by Title II as common carriers.

The key inflection point came in 2002, when a GOP-majority FCC under George W. Bush classified cable internet services as Title I. In effect, the commission stripped itself of its authority to regulate the nascent industry. (Then-FCC Chair Michael Powell subsequently became the chief Washington lobbyist for the cable industry, big surprise.)

Not until 2015 was the error rectified, at the urging of President Obama. Broadband was reclassified under Title II; then-FCC Chair Tom Wheeler was explicit about using the restored authority to enforce network neutrality.

But that regulatory regime lasted only until 2017, when a reconstituted FCC, chaired by a former Verizon executive Ajit Pai, reclassified broadband again as Title I in deference to President Trump’s deregulatory campaign. The big ISPs would have geared up to take advantage of the new regime, had not California and other states stepped into the void by enacting their own net neutrality laws.

A federal appeals court upheld California’s law, the most far-reaching of the state statutes, in 2022. And although the FCC’s action could theoretically preempt the state law, “what the FCC is doing is perfectly in line with what California did,” says Craig Aaron, co-CEO of the consumer advocacy organization Free Press.

The key distinction, Aaron told me, is that the FCC’s initiative goes well beyond the issue of net neutrality — it establishes a single federal standard for broadband and reclaims its authority over the technology more generally, in ways that “safeguard national security, advance public safety, protect consumers and facilitate broadband deployment,” in the commission’s own words.

Although Verizon’s actions in the 2018 wildfire case did not violate the net neutrality principle, for instance, the FCC’s restored regulatory authority might have enabled it to set forth rules governing the provision of services when public safety is at stake that might have prevented Verizon from throttling the Santa Clara Fire Department’s connection in the first place.

Until Thursday, the state laws functioned as bulwarks against net neutrality abuses by ISPs. “California helped discourage companies from trying things,” Aaron says. Indeed, provisions of the California law are explicit enough that state regulators haven’t had to bring a single enforcement case. “It’s been mostly prophylactic,” he says — “telling the industry what it can and can’t do. But it’s important to have set down the rules of the road.”

None of this means that the partisan battle over broadband regulation is over. Both Republican FCC commissioners voted against the initiative Thursday. A recrudescence of Trumpism after the November election could bring a deregulation-minded GOP majority back into power at the FCC.

Indeed, in a lengthy dissenting statement, Brendan Carr, one of the commission’s Republican members, repeated all the conventional conservative arguments presented to justify the repeal of network neutrality in 2017. Carr painted the 2015 restoration of net neutrality as a liberal plot — “a matter of civic religion for activists on the left.”

He asserted that the FCC was then goaded into action by President Obama, who was outspoken on the need for reclassification and browbeat Wheeler into going along. Leftists, he said, “demand that the FCC go full-Title II whenever a Democrat is president.”

Carr also depicted network neutrality as a drag on profits and innovation in the broadband sector. “Broadband investment slowed down after the FCC imposed Title II in 2015,” he said, “and it picked up again after we restored Title 1 in 2017.”

Carr chose his time frame very carefully. Examine the longer period in which net neutrality has been debated at the FCC, and one finds that broadband investment crashed after a Republican-led FCC reclassified broadband as an information service in 2002, falling to $57 billion in 2003 from $111.5 billion in 2001.

Investment did decline between 2015, when net neutrality rules were reinstated, and 2017, when they were rescinded — by a minuscule 0.8%. It hasn’t been especially robust since then — as of 2002 it was still running at only about 92% of what it had been two decades earlier.

As the FCC observed in Thursday’s order, “regulation is but one of several factors that drive investment and innovation in the telecommunications and digital media markets.”

The commission cited consumer demand and the arrival of new technologies, among others. Strong, consistent regulation, moreover, opens the path for new competitors with new ideas and innovations — and can bring prices down for users in the process.

The truth is that network neutrality has been heavily favored by the public, in part because examples of ISPs abusing their power were not hard to find. In 2007, Comcast was caught degrading traffic from the file-sharing service BitTorrent, which held contracts to distribute licensed content from Hollywood studios and other sources in direct competition with Comcast’s pay-TV business.

In 2010, Santa Monica-based Tennis Channel complained to the FCC that Comcast kept it isolated on a little-watched sports tier while giving much better placement to the Golf Channel and Versus, two channels that compete with it for advertising, and which Comcast happened to own. The FCC sided with the Tennis Channel but was overruled by federal court.

Even barring a change at the White House, the need for vigilant enforcement will never go away; ISPs will always be looking for business models and manipulative practices that could challenge the FCC’s oversight capabilities, especially as cable and telecommunications companies consolidate into bigger and richer enterprises and combine content providers with their internet delivery services.

“This is an industry,” Aaron says, “that requires a lot of scrutiny.”

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoMovie Review: The American Society of Magical Negroes

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoIf not Ursula, then who? Seven in the wings for Commission top job

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoGOP senators demand full trial in Mayorkas impeachment

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoCroatians vote in election pitting the PM against the country’s president

-

World1 week ago

World1 week ago'You are a criminal!' Heckler blasts von der Leyen's stance on Israel

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump trial: Jury selection to resume in New York City for 3rd day in former president's trial

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoPon Ondru Kanden Movie Review: This vanilla rom-com wastes a good premise with hasty execution

-

Kentucky1 week ago

Kentucky1 week agoKentucky first lady visits Fort Knox schools in honor of Month of the Military Child