Science

What Nearly Brainless Rodents Know About Weight Loss and Hunger

Do we really have free will when it comes to eating? It’s a vexing question that is at the heart of why so many people find it so difficult to stick to a diet.

To get answers, one neuroscientist, Harvey J. Grill of the University of Pennsylvania, turned to rats and asked what would happen if he removed all of their brains except their brainstems. The brainstem controls basic functions like heart rate and breathing. But the animals could not smell, could not see, could not remember.

Would they know when they had consumed enough calories?

To find out, Dr. Grill dripped liquid food into their mouths.

“When they reached a stopping point, they allowed the food to drain out of their mouths,” he said.

Those studies, initiated decades ago, were a starting point for a body of research that has continually surprised scientists and driven home that how full animals feel has nothing to do with consciousness. The work has gained more relevance as scientists puzzle out how exactly the new drugs that cause weight loss, commonly called GLP-1s and including Ozempic, affect the brain’s eating-control systems.

The story that is emerging does not explain why some people get obese and others do not. Instead, it offers clues about what makes us start eating, and when we stop.

While most of the studies were in rodents, it defies belief to think that humans are somehow different, said Dr. Jeffrey Friedman, an obesity researcher at Rockefeller University in New York. Humans, he said, are subject to billions of years of evolution leading to elaborate neural pathways that control when to eat and when to stop eating.

As they have probed how eating is controlled, researchers learned that the brain is steadily getting signals that hint at how calorically dense a food is. There’s a certain amount of calories that the body needs, and these signals make sure the body gets them.

The process begins before a lab animal takes a single bite. Just the sight of food spurs neurons to anticipate whether a lot of calories will be packed into that food. The neurons respond more strongly to a food like peanut butter — loaded with calories — than to a low-calorie one like mouse chow.

The next control point occurs when the animal tastes the food: Neurons calculate the caloric density again from signals sent from the mouth to the brainstem.

Finally, when the food makes its way to the gut, a new set of signals to the brain lets the neurons again ascertain the caloric content.

And it is actually the calorie content that the gut assesses, as Zachary Knight, a neuroscientist at the University of California San Francisco, learned.

He saw this when he directly infused three types of food into the stomachs of mice. One infusion was of fatty food, another of carbohydrates and the third of protein. Each infusion had the same number of calories.

In each case, the message to the brain was the same: The neurons were signaling the amount of energy, in the form of calories, and not the source of the calories.

When the brain determines enough calories were consumed, neurons send a signal to stop eating.

Dr. Knight said these discoveries surprised him. He’d always thought that the signal to stop eating would be “a communication between the gut and the brain,” he said. There would be a sensation of having a full stomach and a deliberate decision to stop eating.

Using that reasoning, some dieters try to drink a big glass of water before a meal, or fill up on low-calorie foods, like celery.

But those tricks have not worked for most people because they don’t account for how the brain controls eating. In fact, Dr. Knight found that mice do not even send satiety signals to the brain when all they are getting is water.

It is true that people can decide to eat even when they are sated, or can decide not to eat when they are trying to lose weight. And, Dr. Grill said, in an intact brain — not just a brainstem — other areas of the brain also exert control.

But, Dr. Friedman said, in the end the brain’s controls typically override a person’s conscious decisions about whether they feel a need to eat. He said, by analogy, you can hold your breath — but only for so long. And you can suppress a cough — but only up to a point.

Scott Sternson, a neuroscientist with the University of California in San Diego and Howard Hughes Medical Institute, agreed.

“There is a very large proportion of appetite control that is automatic,” said Dr. Sternson, who is also a co-founder of a startup company, Penguin Bio, that is developing obesity treatments. People can decide to eat or not at a given moment. But, he added, maintaining that sort of control uses a lot of mental resources.

“Eventually, attention goes to other things and the automatic process will wind up dominating,” he said.

As they probed the brain’s eating-control systems, researchers were continually surprised.

They learned, for example, about the brain’s rapid response to just the sight of food.

Neuroscientists had found in mice a few thousand neurons in the hypothalamus, deep in the brain, that responded to hunger. But how are they regulated? They knew from previous studies that fasting turned these hunger neurons on and that the neurons were less active when an animal was well fed.

Their theory was that the neurons were responding to the body’s fat stores. When fat stores were low — as happens when an animal fasts, for example — levels of leptin, a hormone released from fat, also are low. That would turn the hunger neurons on. As an animal eats, its fat stores are replenished, leptin levels go up, and the neurons, it was assumed, would quiet down.

The whole system was thought to respond only slowly to the state of energy storage in the body.

But then three groups of researchers, independently led by Dr. Knight, Dr. Sternson and Mark Andermann of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, examined the moment-to-moment activity of the hunger neurons.

They began with hungry mice. Their hunger neurons were firing rapidly, a sign the animals needed food.

The surprise happened when the investigators showed the animals food.

“Even before the first bite of food, the activity of those neurons shut off,” Dr. Knight said. “The neurons were making a prediction. The mouse looks at food. The mouse predicts how many calories it will eat.”

The more calorie-rich the food, the more neurons turn off.

“All three labs were shocked,” said Dr. Bradford B. Lowell, who worked with Dr. Andermann at Beth Israel Deaconess. “It was very unexpected.”

Dr. Lowell then asked what might happen if he deliberately turned off the hunger neurons even though the mice hadn’t had much to eat. Researchers can do this with genetic manipulations that mark neurons so they can turn them on and off with either a drug or with a blue light.

These mice would not eat for hours, even with food right in front of them.

Dr. Lowell and Dr. Sternson independently did the opposite experiment, turning the neurons on in mice that had just had a huge meal, the mouse equivalent of a Thanksgiving dinner. The animals were reclining, feeling stuffed.

But, said Dr. Andermann, who repeated the experiment, when they turned the hunger neurons on, “The mouse gets up and eats another 10 to 15 percent of its body weight.” He added, “The neurons are saying, ‘Just focus on food.’”

Researchers continue to be amazed by what they are finding — layers of controls in the brain that ensure eating is rigorously regulated. And hints of new ways to develop drugs to control eating.

One line of evidence was discovered by Amber Alhadeff, a neuroscientist at the Monell Chemical Senses Center and the University of Pennsylvania. She recently found two separate groups of neurons in the brainstem that respond to the GLP-1 obesity drugs.

One group of neurons signaled that the animals have had enough to eat. The other group caused the rodent equivalent of nausea. The current obesity drugs hit both groups of neurons, she reports, which may be a factor in the side effects many feel. She proposes that it might be possible to develop drugs that hit the satiety neurons but not the nausea ones.

Alexander Nectow, of Columbia University, has another surprise discovery. He identified a group of neurons in the brainstem that regulate how big a meal is desired, tracking each bite of food. “We don’t know how they do it,” he said.

“I’ve been studying this brainstem region for a decade and a half,” Dr. Nectow said, “but when we went and used all of our fancy tools, we found this population of neurons we had never studied.”

He’s now asking if the neurons could be targets for a class of weight loss drugs that could upstage the GLP-1s.

“That would be really amazing,” Dr. Nectow said.

Science

Immigration crackdown could stymie efforts to fight bird flu outbreak, experts fear

As authorities brace for a potential resurgence in bird flu cases this fall, infectious disease specialists warn that the Trump administration’s crackdown on undocumented immigrants could hamper efforts to stop the spread of disease.

Dairy and poultry workers have been disproportionately infected with the H5N1 bird flu since it was first detected in U.S. dairy cows in March 2024, accounting for 65 of the 70 confirmed infections, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

As is the case throughout agriculture, immigrants make up a significant proportion of this workforce and both industry groups and academics say many of these workers probably entered the U.S. illegally. That could spell trouble for a future outbreak of bird flu, infectious disease experts say, making workers reluctant to cooperate with health investigators.

“Most dairy and poultry workers, regardless of their immigration status, are in no way going to be like, ‘hey, government, yeah, of course, check me out, I think I might have H5N1,’” said Angela Rasmussen, a virologist at the University of Saskatchewan’s Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization in Canada.

“No, they’re going to keep their heads down and be as quiet as possible so that they don’t end up at” an immigration detention center, such as Alligator Alcatraz, she said.

Officials with the U.S. Department of Agriculture didn’t respond to requests for comment. Neither did the California Department of Public Health, which has been on the front line of worker testing and safety — offering $25 gift cards to workers who agree to be tested and providing personal protective equipment to farmers and workers.

“To imply that the Trump Administration’s lawful approach to immigration enforcement is somehow suppressing disease reporting is a leap unsupported by evidence and dismissive of the real work being done by the agency,” a spokesperson for the Health and Human Services Administration said in a statement.

Public health officials say the risk of H5N1 infection to the general public is low. People who work with livestock and wild animals are considered to be at elevated risk.

The Trump administration paused immigration arrests at farms, hospitals and restaurants last month, but later reversed course. This month, Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins said that there are plenty of able-bodied Americans to perform farm labor and that there would be “no amnesty” for undocumented farmworkers.

Jennifer Nuzzo, director of the Pandemic Center at Brown University, said that there are two big risks with the administration’s crackdown.

Dairy and poultry workers are on the front line of the virus, handling both diseased and infected animals. If they are too afraid to report symptoms or get tested, “it increases the risk that someone could die because the medicines need to be given early after onset of symptoms,” she said.

Nuzzo said the crackdown also decreases the likelihood that a pandemic could be detected in its early stages.

“The virus needs to change and become easily transmissible between people to cause a pandemic and we need to know about as many infections as possible to track the virus and prevent it from gaining those abilities,” Nuzzo said. “[If] people don’t come forward, we can’t do that.”

In the spring, eight undocumented workers at a Vermont dairy were arrested; four were ultimately deported. The raids sent shock waves through the small, tight-knit dairy industry of New England and sent a message to dairies elsewhere that no place is safe.

Anja Raudabaugh, chief executive of Western United Dairies, California’s largest dairy trade association, said dairy farmers aren’t worried about bird flu, adding that measures are in place to protect workers and to prevent a rapid spread of disease.

From a public health perspective, she said, the state is better positioned than it was last year.

“One of the biggest changes in the ground response to Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) is that the occupational health clinics, ERs, and other rural clinics now have access to the testing equipment necessary to detect the virus (where they didn’t last year),” she said in an email. In addition, the state’s health department has provided the anti-viral medication, Tamiflu, to health clinics “so the workers feel reinforced that their families can be protected.”

The dairy trade group also has no objections to the immigration crackdown.

“America wants this problem solved and dairy farmers are ready to be part of the solution,” Raudabaugh said. “We do not fear ICE. These are good, full-time jobs and we hire anyone who loves cows and wants to work in a quiet, blue-collar family environment.”

Dairy farmer Joey Airoso said the effect on both his workers and cows was minimal when his Pixley dairy was hit by the virus last year.

His bigger concern is “the wide open border that’s let a lot of people into are country that are here for the wrong reasons,” said Airoso, who owns about 2,600 head of cattle.

But Raw Farms dairy owner Mark McAfee said he and his neighboring farmers in Fresno County are “freaked out” by the ICE raids and “want no part of it.”

McAfee’s dairy, which produces raw milk, was shut down by the virus for several months last year. He’s worried not only about the virus returning, but also about immigration agents seizing his workers, many of whom are foreign born.

“Everybody we have is legal, but they (ICE) don’t give a damn about that — they’re picking them up, too,” he said. “Legal status doesn’t mean a lot, and that’s really scary, because that’s something we all relied upon for previous 25 years of operation.”

One question is whether the state will face another big outbreak of bird flu.

There have been only sporadic infections this summer. Detections of the virus in wastewater is low, and in the last 30 days, only two dairy herds — one each in California and Arizona — and one commercial poultry flock in Pennsylvania have reported outbreaks.

But most experts agree that’s likely to change as migrating birds congregate in fields and around lakes as they journey south later this year — passing virus between one another and infecting young birds with no immunity.

“We have 60,000 waterfowl in California right now,” said Maurice Pitesky, a poultry expert at UC Davis. “By late fall, early winter, that number will jump to 6 million.”

Waterfowl — ducks and geese — are considered the primary carriers of the virus.

Since the virus reappeared in North America at the end of 2022, new variants and widespread outbreaks have followed the migrating birds — infecting poultry farms, resident wild birds, wild mammals, such as racoons, mountain lions and skunks, as well as marine and domestic mammals.

In late 2023, the virus made a jump into dairy cattle. And in the fall of 2024, a new variant — the D1.1 version of the virus — sparked a new outbreak in dairy cows, poultry and other animals.

Andrew Ramey, director of the Molecular Ecology Lab at the U.S. Geological Survey’s Alaska Science Center, which monitors for H5N1 in wild bird populations, said one possibility is that the bird flu could return in a more virulent state.

“I think we’re all kind of bracing to see what might happen this fall,” he said.

Science

The mother of an L.A. teen who took his own life is fighting for a new mental health tool for LGBTQ+ youth

Bridget McCarthy believes that if her son Riley Chart had quick and easy access to a suicide prevention hotline designed for queer young people, he might be alive today.

Chart, a trans teen who had once endured bullying because he was different, took his own life at the family’s home during the COVID-19 lockdown in September 2020 — two weeks after his 16th birthday.

“I truly believe that had there been an LGBTQ-specific [help] number right in front of him, he would’ve tried it,” McCarthy said.

Riley Chart with his mother Bridget McCarthy.

(Paul Chart)

State lawmakers are set to vote in August on a bill that McCarthy and its sponsors say could save the lives of other young queer Californians.

California Assembly Bill 727 would require ID cards for public school students in grades 7 through 12 and students at public institutions of higher education to list the free LGBTQ+ crisis line operated by The Trevor Project on the back, starting in July 2026.

The Trevor Project is a West Hollywood-based nonprofit that the federal government cut ties with when it eliminated funding for LGBTQ+ counseling through the National Suicide and Crisis Lifeline (9-8-8). The lifeline was expected to stop routing crisis calls to The Trevor Project and six other LGBTQ+ contractors Thursday. It’s one of several actions in the second Trump administration that critics fear will roll back years of progress of securing health-care services for queer Americans.

“When the Trump administration threatened and then went through with their threat to cut the program completely, that told us that we had to step up to the plate,” said Democratic Assemblymember Mark González of Los Angeles, who said he introduced the legislation to ensure that queer youth receive support from counselors who can relate to their life experiences. “Our goal here is to be the safety net — especially for those individuals who are not in Los Angeles but in other parts of the state who need this hotline to survive.”

California Lt. Gov. Eleni Kounalakis, the L.A. LGBT Center and the Sacramento LGBT Center all have signed on as co-sponsors of the bill. Gov. Gavin Newsom told Politico the Trump administration’s 9-8-8 decision was “indefensible” and that he also backs the bill. His office said the state’s $4.7 billion Master Plan for Kids’ Mental Health includes partnerships with organizations such as The Trevor Project.

González said the bill originally included private schools but in response to conservative opposition, the mandate was amended so it would be limited to public schools.

With federal funding for the LGBTQ+ crisis counselors who field calls through the 9-8-8 lifeline running out on Thursday, local nonprofits and elected officials have vowed to fill the void. L.A. County Supervisors Janice Hahn and Lindsey P. Horvath authored a motion to explore the impact of the cut and see whether the county can help to continue the service. The board unanimously approved it Tuesday.

“The federal government may be turning its back on LGBTQ+ people, but here in L.A. County we’ll do everything within our power to keep this community safe,” Hahn said in a statement after the vote.

About 40% of young queer people in the U.S. have seriously contemplated suicide compared to 13% of their peers, according to a teen mental health survey published last fall by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Trevor Project and other organizations have reported a rise in the number of people calling crisis lines to seek mental health support, both in California and nationwide.

Trans Americans have been particularly shaken by the backlash against LGBTQ+ people and by the prospect of new restrictions on gender-affirming healthcare, according to new findings published this week by researchers at the University of Vermont.

Their survey of 489 gender-diverse adults after the 2024 election, published Wednesday in JAMA Open Network, found that nearly a third of those interviewed would consider risky DIY hormone therapies if treatments disappear elsewhere. A fifth of respondents reported having suicidal thoughts.

Riley Chart with his father, Paul Chart.

(Bridget McCarthy)

As the mother of a trans child who died from suicide, McCarthy said she wants to use the lessons she’s learned to educate and advocate for other trans young people and their families in similar situations.

McCarthy, who lives in Culver City, has started a memorial fund with The Trevor Project, organized suicide prevention walks in West L.A. and attended Pride festivals to hand out crisis line information.

She remembers Riley as an artistic and warmhearted son who joined LGBTQ+ groups and built a network of friends while attending high schools in both Santa Monica and Culver City.

Riley had a therapist for support living as a trans teen, but during the pandemic, he found it hard to cope with not being able to spend time in person with his friends. The confinement made him increasingly irritable. He was staying up later than usual and spending excessive time on his phone, McCarthy said.

After Riley died, the family discovered that he’d texted a gay friend for help.

“The only other number in his phone was a 10-digit veterans hotline number — that he did not call,” McCarthy said. “That’s why you have to have a lifeline that speaks to different populations. A veterans hotline will not work for a 16-year-old kid who’s struggling with their identity.”

When Riley was 12, McCarthy took him to the Pride parade in West Hollywood hoping that he would experience the feeling of belonging that he seemed to yearn for. He loved it.

Riley Chart attending West Hollywood Pride in 2017.

(Bridget McCarthy)

“Ry said he’d found his people,” McCarthy recalls, using the family’s nickname for him. “He was like, ‘This is it — I’m home, mom.’”

When Riley’s mother took him to Pride a second time the following year, he bought a trans pride flag that became one of his prized possessions. “He was wrapped in it when he went, when he left us,” McCarthy said.

McCarthy spoke by phone from one of Riley’s favorite places, Lummi Island in Washington state, near the U.S.-Canada border. The family laid Riley’s remains on the island and McCarthy goes to visit the grave site four times a year to care for the maple tree planted in his memory, admire the painted stones his friends placed around it and talk to her son.

McCarthy said she and Riley visited family friends on the island almost every year when he was younger. Especially during middle school when he faced bullying from classmates and issues over which restroom to use, the island served as a refuge where McCarthy saw her son at his most carefree. He loved climbing trees, swimming and herding cows, far from the pressures of being a kid in L.A.

“When you’d open the car door, it was just like opening the barn gate,” McCarthy remembers. “Like a colt across a field, he would just run. It gave us a chance for some peace.”

Science

Foreign, feral honeybees are crowding out native bee species in southern California

You’ve probably heard the phrase: “Save the bees.” But new research suggests we may need to be more specific about which bees we’re saving.

Europeans introduced western honeybees (Apis mellifera L.) to the Americas in the early 1600s. They play an essential role in pollinating crops and flowering plants, and are often hailed as the “unsung heroes of our planet.” They are both omnivorous and omnipresent: Researchers have found that western honeybees visit more plant species than any other species of pollinator and are the most common visitor to plants in non-managed habitats worldwide, accounting for nearly 13% of all floral visitors.

The problem is that this dominance may be coming at the cost of some native pollinators.

That’s what caught the attention of Joshua Kohn, a former biology professor at UC San Diego. “Pollination biologists in general in North America tend to ignore western honeybees because they’re not native,” he said. “But when I saw just how abundant they were, I thought to myself: They’re not just a nuisance, they’re the story.”

In San Diego County — a global bee biodiversity hotspot — feral honeybee populations have quietly exploded in number since the late 1960s. Many of these bees trace their ancestry to a hybrid of European and African subspecies, the latter known for traits that boost survival in hot, dry climates — places with mild winters and vegetation that blooms year-round. In other words, perfect for Southern California, where previously domesticated populations became feral colonies that thrived independent of human management, nesting in rock crevices, abandoned rodent burrows and other natural cavities.

However, despite their population growth and spread, researchers don’t know much about these bees’ pollen consumption, or the extent to which their foraging habits may be displacing native species.

A new study published July 7 in the journal Insect Conservation and Diversity seeks to address that knowledge gap. Drawing from field surveys in San Diego’s coastal scrubland, researchers at UC San Diego found that feral honeybees — non-native, unmanaged descendants of domesticated bees — may be monopolizing local ecosystems and effectively squeezing out native pollinators such as bumblebees. In total, these feral bees now comprise about 90% of all bees in the area, according to the study.

“It’s like going to the Amazon rainforest to bird-watch and seeing only pigeons,” said James Hung, an ecologist at the University of Oklahoma and co-author of the study. “I was shocked. This was supposed to be a biodiversity hotspot — but all we were seeing were honeybees.”

The team also wanted to understand how honeybee foraging affected pollen availability for native species, and what that might mean for the latter’s ability to reproduce successfully. The researchers looked at how honeybees interacted with three native plants: black sage, white sage and distant phacelia. They found that in just two visits, a western honeybee could remove more than 60% of the pollen from these flowers. By the end of a single day for all three plant species analyzed, more than 80% of all pollen was gone.

The problem is that this leaves almost no pollen for native bees.

Kohn, a co-author of the study, explained that while western honeybees are prolific foragers, they aren’t always the most effective pollinators. His previous research suggests plants pollinated by these bees often produce less fit offspring, in part due to inbreeding. This is because western honeybees tend to visit many flowers on the same plant before moving on — a behavior that increases the risk of self-fertilization.

What this means for the broader plant community is still unclear, Kohn said. “But it’s likely that the offspring of plants would be more fit if they were pollinated by native pollinators. It’s possible that if honeybees were not in the system that there’d be more bumblebees, which visit flowering plants much more methodically.”

Kohn emphasized that the findings aren’t an argument against honeybee conservation, especially given their importance to agriculture. However, they do suggest we may need to reconsider how to manage domesticated western honeybee populations.

When used for agricultural pollination, managed honeybees are often brought into an area temporarily in what’s called a mobile apiary: essentially, dozens or hundreds of hives kept on a trailer or platform, moved from place to place, wherever pollination is needed. While this is essential for crops, stripping nectaring plants of resources before native species have a chance to feed could lead to their decimation.

Hung suggested designating specific forage zones for commercial beekeeping — ideally in areas less vulnerable to ecological disruption — as a way to offset that pressure. “If we can identify ecosystems that are less sensitive to disturbance — those with a lower number of endemic plant or pollinator species — we could scatter seed mixes and produce way more flowers than any comparable habitat nearby,” he said. “Then, we could set aside some acres of land for beekeepers to come and park their bees and let them forage in a way that does not disrupt the native ecosystem. This would address the conflict between large-scale managed honeybee populations and the wild bees that they could potentially be impacting.”

Rather than replacing crop pollination, the idea would be to offer alternative foraging options that keep honeybees from spilling into and dominating natural areas.

Longer-term, Hung said scientists may need to consider more direct forms of intervention, such as relocation or eradication. “Honeybees have dug their roots very deep into our ecosystem, so removing them is going to be a big challenge,” he said. But at some point, he believes, it may be necessary to protect native plants and pollinators.

In the words of Scott Black, director of the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation, “Keeping honeybees to ‘save the bees’ is like raising chickens to save birds.”

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: Clashes After Immigration Raid at California Cannabis Farm

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoTrump heads to Texas as recovery efforts from deadly flood continue

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoNew amnesty law for human rights abuses in Peru prompts fury, action

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoMaalik Movie Review – Gulte

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

‘Doora Theera Yaana’ movie review: Mansore’s mature take on relationships is filled with relatable moments

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoIt’s the final day of Prime Day 2025, and the deals are still live

-

Politics1 week ago

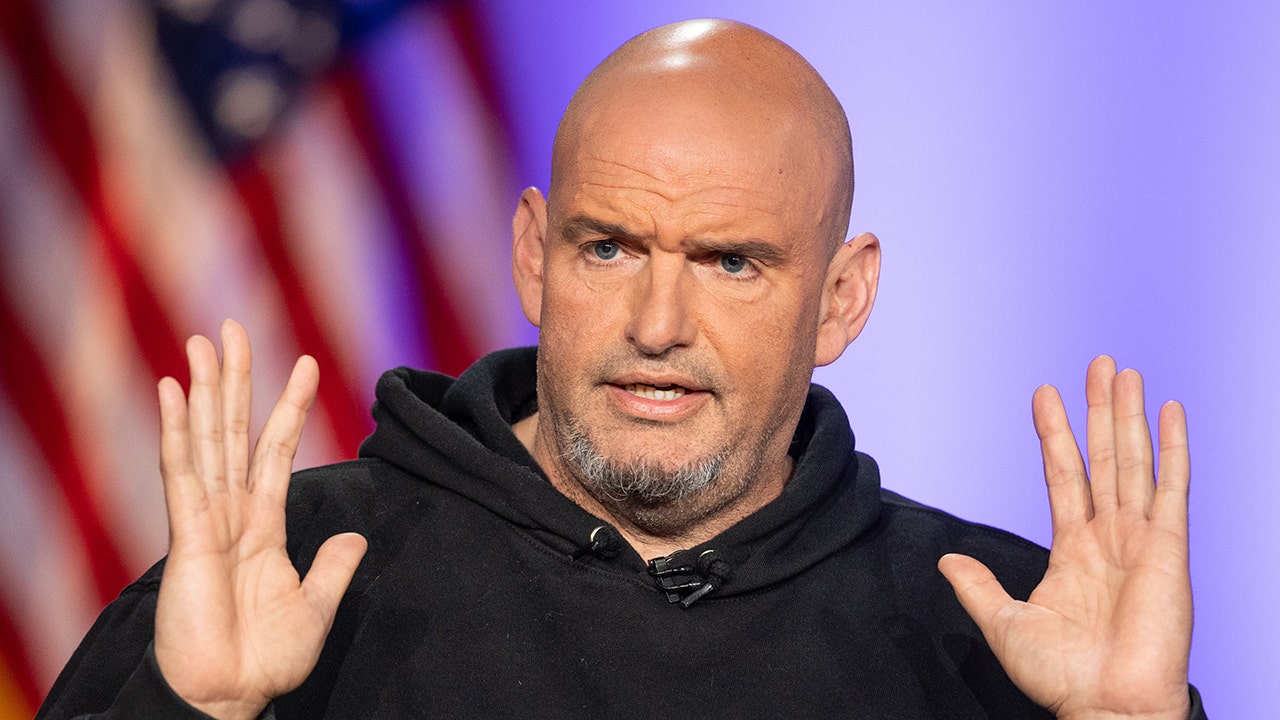

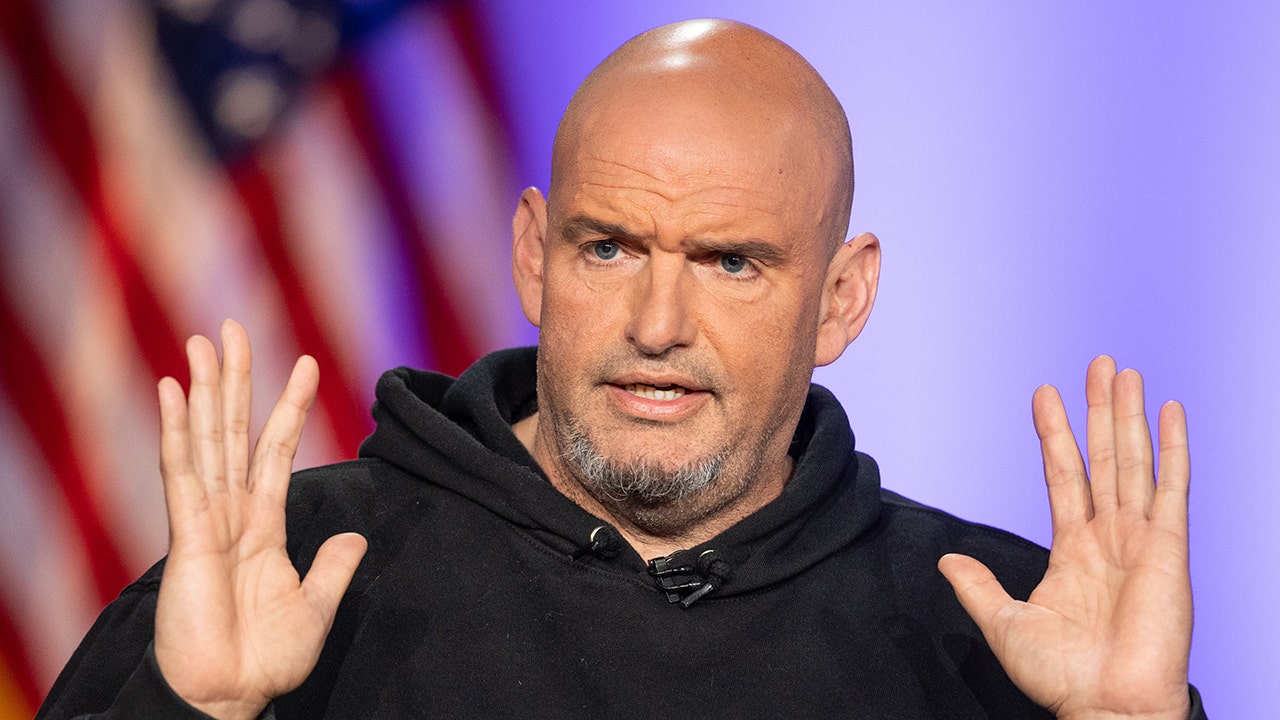

Politics1 week agoDemocrat John Fetterman declares support for ICE, condemning any calls for abolition as 'outrageous'

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoRussia-Ukraine war: List of key events, day 1,235