Science

Pregnant and addicted: Homeless women see hope in street medicine

Five days after giving birth, Melissa Crespo was already back on the streets, recovering in a damp, litter-strewn water tunnel, when she got the call from the hospital.

Her baby, Kyle, who had been born three months prematurely, was in respiratory failure in the neonatal intensive care unit and fighting for his life.

The odds had been against Kyle long before he was born last summer. Crespo, who was abused as a child, was addicted to fentanyl and meth — a daily habit she found impossible to kick while living homeless.

Crespo got a ride to the hospital and cradled her baby in her arms as he died.

“I know this happened because of my addiction,” Crespo said recently, just after a nurse injected her on the streets of downtown Redding with a powerful antipsychotic medication. “I’m trying to get clean, but this is an illness and it’s so hard while you’re out here.”

Crespo, 39, is among a growing number of homeless pregnant women in California whose lives have been overrun by hard drug use, a deadly coping mechanism many use to endure trauma and mental illness. They are a largely unseen population that, in battling addiction, has lost children — whether to death or local child welfare authorities.

She and other women are now receiving care from specialized street medicine teams fanning across California to treat homeless people wherever they are — whether in squalid encampments, makeshift shantytowns clustered along rivers, or vehicles they stealthily maneuver from one neighborhood to another in search of a safe place to park.

Dr. Kyle Patton leads the street medicine team for Shasta Community Health Center in Redding.

(Angela Hart / KFF Health News)

“This is a really impoverished community, and the big thing right now is maternity care and prenatal care,” said Kyle Patton, a family doctor who leads the street medicine team for Shasta Community Health Center in Redding, about 160 miles north of Sacramento in a largely rural and conservative part of the state.

Patton, who dons hiking boots and jeans to make his rounds, has managed about 20 pregnancies on the streets since early 2022, and even totes a portable ultrasound in his backpack to find out how far along women are. He’s also helping homeless mothers who have lost custody of their children try to get sober so they can reunite.

“I didn’t expect this to be a huge part of my practice when I got into street medicine,” Patton said on a hot June day as he packed his medical van with birth control implants, tests to diagnose syphilis and HIV, antibiotics and other supplies.

“The system is broken and people lack access to healthcare and housing, so managing pregnancies and providing prenatal care has become a really big part of my job.”

Street medicine isn’t new, but it’s getting a jolt in California, which is leading the charge nationally to deliver full-service medical care and behavioral health treatment to homeless people wherever they are.

Kerry Hankins receives a shot of antipsychotic medication from Shasta Community Health Center nurse Anna Cummings.

(Angela Hart / KFF Health News)

The practice is exploding under Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom, whose administration has plowed tens of billions of dollars into health and social services for homeless people. It has also standardized payment for street medicine providers through the state’s Medicaid program, called Medi-Cal, allowing them to be paid more consistently. The federal government expanded reimbursement for street medicine this month, making it easier for doctors and nurses around the country to get paid for delivering care to homeless patients outside of hospitals and clinics.

State health officials and advocates of street medicine say it fills a critical gap in healthcare — and could even help solve homelessness. Not only are homeless people receiving specialized treatment for addiction, mental illness, chronic diseases and pregnancy, but they’re also getting help enrolling in Medi-Cal and food assistance, and applying for state identification cards and federal disability payments.

In rare cases, street medicine teams have gotten some of the state’s sickest and most vulnerable people healthy and into housing, which supporters point to as incremental but meaningful progress. Yet they acknowledge that it’s no quick fix, and that the expansion of street medicine signals an acceptance that homelessness isn’t going away anytime soon — and that there may never be enough housing, homeless shelters and treatment beds for everyone living outside.

“Even if there is all the money and space to build it, local communities are going to fight these projects,” said Barbara DiPietro, senior director of policy for the Tennessee-based National Health Care for the Homeless Council. “So street medicine is shifting the idea to say, ‘If not housing, how can we manage folks and provide the best possible care on the streets?’”

The expansion of street medicine and other services doesn’t always play well in communities overwhelmed by growing homeless populations — and the rise in local drug use, crime and garbage that accompany encampments. In Redding and elsewhere, many residents, leaders and business owners say that expanding street medicine merely enables homelessness and perpetuates drug use.

Tara Darby, who is homeless, found out she was pregnant over the summer when street medicine doctor Kyle Patton was preparing to get her on an anti-addiction treatment.

(Angela Hart / KFF Health News)

Patton acknowledges the process of getting people off drugs is long and messy. More often than not, they relapse, he said, and most expectant mothers lose their babies.

This is true even of homeless mothers like Crespo, who has been using hard drugs for nearly two decades but is desperate to get clean so she can reconnect with her four estranged children, ages 12 to 24, Crespo said. Two other children have died, one from lymphoma at age 15 and baby Kyle in August 2022, primarily because of complications from congenital syphilis.

Patton is treating Crespo for mental illness and addiction and has implanted long-acting birth control into her arm so she won’t have another unexpected pregnancy. He has also treated her for hepatitis C and early signs of cervical cancer.

Although she’s still using meth — as is her boyfriend, Kyle’s father — she’s six months sober from fentanyl and heroin, which are more deadly and addictive. “You’d think I could just get clean, but it doesn’t work that way,” Crespo said. “It’s an ongoing fight, but I’m healing.”

Patton doesn’t see Crespo’s continued drug use as a failure. His goal is to establish trust with his patients because overcoming addiction — which often is rooted in trauma or abuse — can take a lifetime, he said.

“We’re playing the long game with our patients,” he said. “They’re really motivated to seek treatment and get off the streets. But it doesn’t always work out that way.”

Patton is a young doctor. At 38, he’s on the leading edge of a movement to entrench street medicine in California, home to nearly a third of all homeless people in America. He has specialized in taking care of low-income patients from the start, first as an outreach worker in Salt Lake City and, later, in a family medicine residency in Fort Worth focused on street medicine.

In the last two years, the number of street medicine teams operating in California has doubled to at least 50, clustered primarily in Los Angeles and the San Francisco Bay Area, with 20 more in the pipeline, said Brett Feldman, director of street medicine at USC’s Keck School of Medicine.

Street medicine nurse Anna Cummings, right, prepares an injection while Keri Weinstock, left, a psychiatric nurse practitioner, speaks with homeless patient Linda Wood.

(Angela Hart / KFF Health News)

Teams are usually composed of doctors, nurses and outreach workers, and are funded largely by health insurers, hospitals and community clinics that serve homeless people who have trouble showing up to appointments. That may be because they don’t have transportation, don’t want to leave pets or belongings unattended in camps, or are too sick to make the trip.

Feldman, who helped persuade Newsom’s administration to expand street medicine, notched a critical success in late 2021 when the state revamped its medical billing system to allow healthcare providers to charge the state for street medicine services. Medi-Cal had been denying claims because providers had treated patients in the field, not in hospitals or clinics.

“We didn’t even realize our system was denying those claims, so we updated thousands of codes to say street medicine providers can treat people in a homeless shelter, in a mobile unit, in temporary lodging or on the streets,” said Jacey Cooper, the state Medicaid director, who this month leaves for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to work on federal Medicaid policy. “We want to transition these women into housing and treatment to give them more hope of keeping their kids.”

The state isn’t pumping new money into street medicine, but primarily redirecting Medicaid funds that would have paid for services in bricks-and-mortar facilities.

Cooper has also pushed insurance companies that cover Medi-Cal patients to contract directly with street medicine teams, and some have done so.

Lauren Hansen says she started using drugs after losing her baby in November. She endured a painful recovery in a roadside encampment in Redding.

(Angela Hart / KFF Health News)

Health Net, with about 2.5 million Medi-Cal enrollees across 28 counties, has contracted with 13 street medicine organizations across the state, including in Los Angeles, and is funding training.

“It’s a better use of taxpayer funding to pay for street medicine rather than the emergency room or constantly calling an ambulance,” said Katherine Barresi, senior director of health services for Partnership HealthPlan of California, which serves 800 homeless patients in Shasta County and contracts with Shasta Community Health Center.

Redding is the county seat of Shasta County, which has experienced a major political upheaval in recent years, driven in part by the anti-vaccine, anti-mask fervor that ignited during the COVID-19 pandemic and the Trump presidency.

Yet residents of all political stripes are growing frustrated by the surge in homelessness and open-air drug use — and the spillover effects on neighborhoods — and are pressuring officials to clear encampments and force people into treatment.

“I don’t care if you’re left, right, middle — what’s happening here is out of control,” said Jason Miller, who owns a sandwich shop called Lucky Miller’s Deli & Market. Miller said he’s had his windows smashed three times — costing $4,500 in repairs — and has caught homeless people defecating and performing lewd acts in his doorway.

Miller moved to Redding 15 years ago from Portland, Ore., after losing patience with the homeless crisis there, and tries to help, handing out shoes and food. He said he also understands that many homeless people need more services, such as street medicine.

“I get what they’re trying to do,” he said of street medicine providers. “But there’s a lot of questioning in the community around what they do. There’s no accountability.”

Patton isn’t deterred by the community’s skepticism or the cycle of addiction, even among his pregnant patients. The way he sees it, his job is to provide the best healthcare he can, no matter the condition his patients are in.

“It’s a lot of wasted energy, judging people and labeling them as noncompliant,” he said. “My job isn’t to determine if a patient is deserving of healthcare. If a patient is sick or has a disease, I have the skills to help, so I’m going to do it.”

Shasta County, like much of California, is seeing its homeless population explode — and get sicker. An on-the-ground count this year identified 1,013 homeless people in the county, up 27% from 2022. Most are men, but women account for a growing share of Patton’s patients because “more and more are getting pregnant,” he said.

Stephanie Meyers has given birth to four children while living on the streets. Street medicine doctor Kyle Patton implanted long-acting birth control in her arm in June.

(Angela Hart / KFF Health News)

County welfare agencies have little choice but to separate babies from their mothers when substance use or homelessness presents a risk to the children, said Amber Middleton, who oversees homelessness initiatives at Shasta Community Health Center.

“We are off the charts with maternal substance abuse,” said Middleton, who previously worked for Shasta County’s child welfare agency. “A lot of these women are trying to get clean so they can get their children back, but they’re also trying to give themselves the childhood that they never had.”

Crespo turned to alcohol and drugs to deal with deep emotional pain from her youth, when she was passed among family members and, she said, beaten repeatedly by one of them. “He would give me black eyes and I would run away,” she recalled in tears, admitting that she has perpetuated that cycle of violence by punching her former husband when she felt provoked.

She has overdosed “more times than I can remember,” she said, and she credits naloxone, an opioid overdose reversal drug, for saving her life repeatedly.

Patton routinely tests Crespo and other patients for sexually transmitted infections, gets them on prenatal vitamins and treats underlying conditions such as high blood pressure that can lead to a high-risk pregnancy. And he’s helping women get sober, often using a drug called Suboxone, which is a combination of two medications used to treat opioid addiction. Its forms include a strip that providers snip to make the needed dose.

“A lot of these women have already had children removed, and many are pregnant again,” he said. “If I can get them on Suboxone, they’re going to have a better chance of being successful as a family when they deliver.”

On that sweltering June day, he met Tara Darby, who was on fentanyl and meth and living in a tent along a creek that feeds into the Sacramento River. Patton started her on a course of Suboxone and got her into a hotel with her boyfriend to help her deal with the initial detox.

He also administered a pregnancy test and discovered she was already a few months along. “It’s rough out here. There’s no bathroom or water, you’re nauseous all the time,” Darby, 40, said. “I want to get out of this situation, but I’m terrified about getting clean, the detox, having my baby.”

When Patton offered her support from a drug and alcohol treatment counselor, Darby promised to try. “I want to do it. I have the willpower,” she said.

Across town, Kristen St. Clair was nearly seven months pregnant and living in a hotel paid for by Shasta Community Health Center. Patton was helping her and her boyfriend, Brandt Clifford, get off fentanyl. “I want to have a healthy, happy life with my baby,” said St. Clair, 42, who already had one baby taken from her largely because of her drug use. “I’m worried it’s too late now.”

But the prospect of getting clean felt daunting. Clifford, the father of her child, is an Iraq war veteran with a traumatic brain injury. He had overdosed the previous day and needed five doses of naloxone to come back. “We saved your life, man,” Patton told Clifford.

Patton snipped a strip of Suboxone, explaining that addiction is complicated.

“Science is showing that, for whatever reason, certain people were born with the right mix of genetic predisposition and then have had various things happen to them in their lives, which are unfair,” he said. “And then when you tried opioids for the first time, your brain said to you, ‘This is the way I am supposed to feel.’ It takes very little to get hooked.”

Despite their desperation to kick their drug habit, St. Clair and Clifford have since relapsed, Patton reported. St. Clair delivered in early September, and her boy was taken into custody to “withdraw in a neonatal abstinence program,” Patton said.

Darby, who was evicted from her hotel room after relapsing, was in residential treatment to get sober as of early October.

Crespo is making headway, Patton said. She and her boyfriend, Andy Gothan, 43, are staying at a hotel while Patton’s team helps her look for a landlord who will accept a low-income housing voucher.

“I’m so close, they’ve helped me so much,” Crespo said. Meth is “always around, always available. If I can get inside, it’ll help me deal with the stress of getting clean without all those triggers.”

This article was produced by KFF Health News, a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues.

Science

Maps of Two Cicada Broods, Reunited After 221 Years

This spring, two broods of cicadas will emerge in the Midwest and the Southeast, in their first dual appearance since 1803.

A cicada lays eggs in an apple twig.

“Insects: Their Ways and Means of Living,” by Robert E. Snodgrass, 1930, via the Biodiversity Heritage Library

Brood XIII, the Northern Illinois Brood, hatched and burrowed into the ground 17 years ago, in 2007.

Brood XIX, the Great Southern Brood, hatched in 2011 and has spent 13 years underground, sipping sap from tree roots.

The entomologist Charles L. Marlatt published a detailed map of Brood XIX, the largest of the 13-year cicada broods, in 1907.

Historic map of cicada emergence.

He also mapped the expected emergence of Brood XIII in 1922.

Historic map of cicada emergence.

This spring the two broods will surface together, and are expected to cover a similar range.

Modern map of cicada emergence.

Up to a trillion cicadas will rise from the warming ground to molt, sing, mate, lay eggs and die.

A Name and a Number

Charles L. Marlatt proposed using Roman numerals to identify the regional groups of 13- and 17-year periodical cicadas, beginning with Brood I in 1893.

A brood can include up to three or four cicada species, all emerging at the same time and singing different songs. Long cicada lifespans of 13 or 17 years spent underground have spawned many theories, and may have evolved to reduce the likelihood of different broods surfacing at the same time.

Large broods might sprawl across a dozen or more states, while a small brood might only span a few counties. Brood VII is the smallest, limited to a small part of New York State and at risk of disappearing.

At least two named broods are thought to have vanished: Brood XXI was last seen in 1870, and Brood XI in 1954.

Not Since the Louisiana Purchase

Brood XIII and Brood XIX will emerge together this year, for the first time in more than two centuries. But only in small patches of Illinois are they likely to come out of the ground in the same place.

In 1786 and 1790, the two broods burrowed into Native lands, divided by the Mississippi River into nominally Spanish territory and the new nation of the United States.

An historic map of the United States from 1783.

Brood XIII entered the ground in 1786, and Brood XIX in 1790. (Expected 2024 ranges are overlaid on the map.)

An historic map of the United States from 1783.

As the ground was warming in April 1803, France sold the rights to the territory of Louisiana, which it acquired from Spain in 1800, to the United States for $15 million.

An historic map of the United States from 1801. That spring, Brood XIII and Brood XIX emerged together into a newly enlarged United States.

An historic map of the United States from 1803.

Their descendants — 13 and 17 generations later — are now poised to return, and will not sing together again until 2245. An historic map of the United States from 1868.

A ‘Great Visitation’

After an emergence of Brood X cicadas in 1919, the naturalist Harry A. Allard wrote:

Although the incessant concerts of the periodical cicadas persisting from morning until night became almost disquieting at times, I felt a positive sadness when I realized that the great visitation was over, and there was silence in the world again, and all were dead that had so recently lived and filled the world with noise and movement.

It was almost a painful silence, and I could not but feel that I had lived to witness one of the great events of existence, comparable to the occurrence of a notable eclipse or the invasion of a great comet.

Then again the event marked a definite period in my life, and I could not but wonder how changed would be my surroundings, my experiences, my attitude toward life, should I live to see them occur again seventeen years later.

The transformation of a cicada nymph (1), into an adult (10).

“The Periodical Cicada,” by Charles L. Marlatt, 1907, via the Biodiversity Heritage Library

Science

What are the blue blobs washing up on SoCal beaches? Welcome to Velella velella Valhalla

The corpses are washing up by the thousands on Southern California’s beaches: a transparent ringed oval like a giant thumbprint 2 to 3 inches long, with a sail-like fin running diagonally down the length of the body.

Those only recently stranded from the sea still have their rich, cobalt-blue color, a pigment that provides both camouflage and protection from the sun’s UV rays during their life on the open ocean.

Aggressive and impactful reporting on climate change, the environment, health and science.

These intriguing creatures are Velella velella, known also as by-the-wind sailors or, in marine biology circles, “the zooplankton so nice they named it twice,” said Anya Stajner, a biological oceanography PhD student at UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

A jellyfish relative that spends the vast majority of its life on the surface of the open sea, velella move at the mercy of the wind, drifting over the ocean with no means of locomotion other than the sails atop their bodies. They tend to wash up on the U.S. West Coast in the spring, when wind conditions beach them onshore.

Springtime velella sightings documented on community science platforms like iNaturalist spiked both this year and last, though scientists say it’s too early to know if this indicates a rise in the animal’s actual numbers.

Velella are an elusive species whose vast habitat and unusual life cycle make them difficult to study. Though they were documented for the first time in 1758, we still don’t know exactly what their range is or how long they live.

These beaching events confront us with a little-understood but essential facet of marine ecology — and may become more common as the oceans warm.

“Zooplankton” — the tiny creatures at the base of the marine food chain — “are sort of this invisible group of animals in the ocean,” Stajner said. “Nobody really knows anything about them. No one really cares about them. But then during these mass Velella velella strandings, all of a sudden there’s this link to this hidden part of the ocean that most of us don’t get to experience.”

What looks like an individual Velella velella is actually a colony of teeny multicellular animals, or zooids, each with their own function, that come together to make a single organism. They’re carnivorous creatures that use stinging tentacles hanging below the surface to catch prey such as copepods, fish eggs, larval fish and smaller plankton.

Unlike their fellow hydrozoa, the Portuguese man o’ war, the toxin in their tentacles isn’t strong enough to injure humans. Nevertheless, “I wouldn’t encourage anyone to touch their mouth or their eyes after they pick one up on the beach,” said Nate Jaros, senior director of fishes and invertebrates at the Aquarium of the Pacific in Long Beach.

Velella that end their lives on California beaches typically have sails that run diagonally from left to right along the length of their bodies, an orientation that catches the onshore winds heading in this direction. As the organism’s carcass dries in the sun and the soft tissues decay, the blue color disappears, leaving the transparent chitinous float behind.

“The wind really just brings them to our doorstep in the right conditions,” Jaros said. “But they’re designed as open ocean animals. They’re not designed to interact with the shoreline, which is usually why they meet their demise when they come into contact with the shore.”

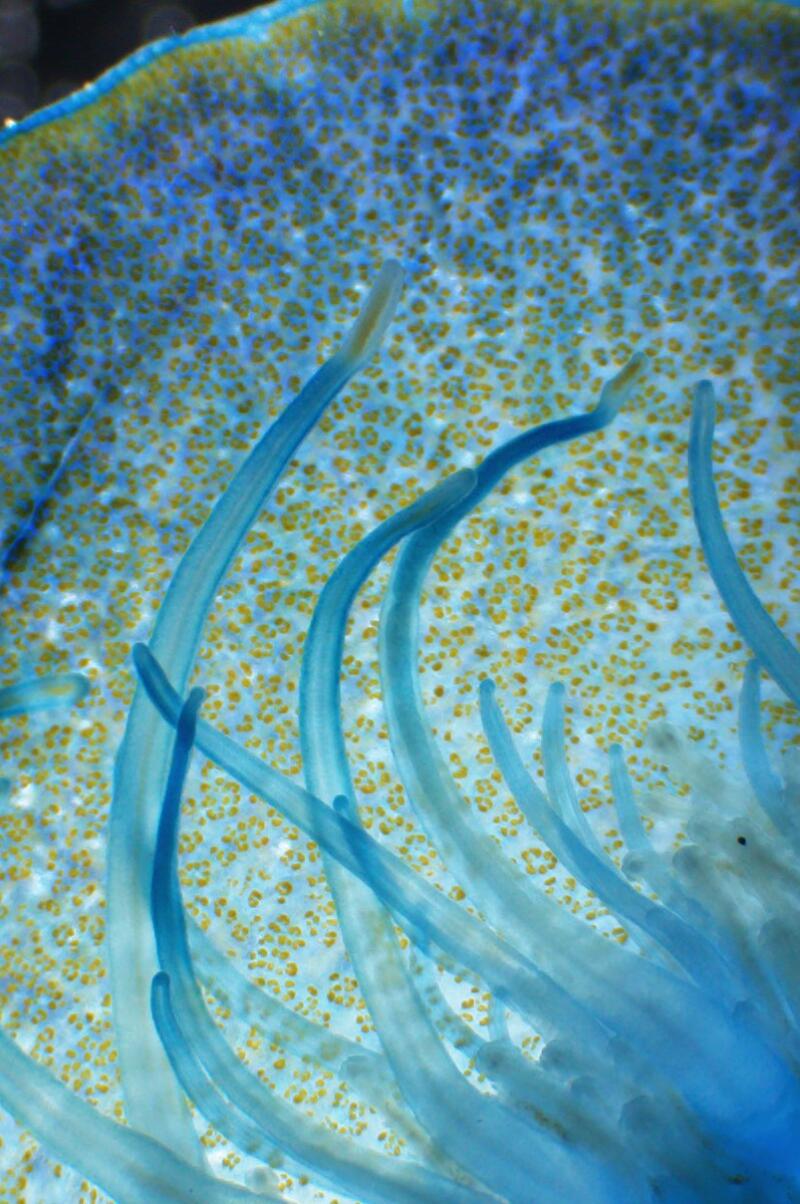

1

2

3

1. Anya Stajner put Velella velella under a microscope. 2. Magnified, you can see more than blue in the organism. “That green and brown coloration comes from their algae symbionts,” Stajner said. 3. Notice the tentacles too. (Anya Stajner)

Velella show up en masse when two key factors coincide, Stajner said: an upwelling of food-rich, colder water from deeper in the ocean, followed by shoreward winds and currents that direct the colonies to beaches.

A 2021 paper from researchers at the University of Washington found a third variable that appears to correlate with more velella sightings: unusually high sea surface temperatures.

After looking at data over a 20-year period, the researchers found that warmer-than-average winter sea surface temperatures followed by onshore winds tended to correlate with higher numbers of velella strandings the following spring, from Washington to Northern California.

“The spring transition toward slightly more onshore winds happens every year, but the warmer winter conditions are episodic,” said co-author Julia K. Parrish, a University of Washington biologist who runs the Coastal Observation and Seabird Survey Team community science project.

Given that sea surface temperatures have been consistently above the historical average every day since March 2023, the current velella bloom is consistent with those findings.

Previous research has found that gelatinous zooplankton like velella and their fellow jellyfish thrive in warmer waters, portending an era some scientists have referred to as the “rise of slime.”

Other winners of a slimy new epoch would be ocean sunfish, a giant bony fish whose individuals can clock in at more than 2,000 pounds and consume jellyfish — and velella — in mass quantities. Ocean sunfish sightings tend to rise when velella observations do, Jaros said.

“The ocean sunfish will actually kind of put their heads out of the water as they eat these. It resembles Pac-Man eating pellets,” he said. (KTLA-TV published a picture of just that this week.)

Though velella blooms are ephemeral, we don’t yet know how long any individual colony lives. The blue seafaring colonies are themselves asexual, though they bud off tiny transparent medusas that are thought to go to the deep sea and reproduce sexually there, Stajner said. The fertilized egg then evolves into a float that returns to the surface and forms another colony.

Anya Stajner, a PhD student at Scripps, collected by-the-wind sailors but was unable to keep them alive in a lab. “Rearing gelatinous organisms is pretty difficult,” she said.

“I was able to actually collect some of those medusae last year during the bloom, but rearing gelatinous organisms is pretty difficult,” Stajner said. The organisms died in the lab.

Stajner left May 1 on an eight-day expedition to sample velella at multiple points along the Santa Lucia Bank and Escarpment in the Channel Islands, with the goal of getting “a better idea of their role in the local ecosystem and trying to understand what these big blooms mean,” she said.

Science

Column: How the GOP — with Democratic Party connivance — has undermined a crucial effort to avert the next pandemic

We’ve all come to recognize that committee hearings conducted by the Republican House majority are almost invariably clown shows featuring spittle-flecked posturing by members intent on displaying their ignorance to an appreciative crowd.

Wednesday’s hearing by the Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Pandemic was a crystalline example of the genre. It was designed around the grilling of Peter Daszak, the head of EcoHealth Alliance, which oversees international virus research funded by federal agencies.

The members scraped along rock-bottom, but the most telling moment may have been this exchange between Rep. Morgan Griffith (R-Va.) and Daszak. Asked to explain an apparent (but not real) discrepancy in a progress report EcoHealth submitted to the government, Daszak started to answer, but a theatrically fulminating Griffith cut him off.

Our organization, staff, and even my own family were often targeted with false allegations, death threats, break-ins, media harassment, and other damaging acts.

— Peter Daszak, EcoHealth Alliance

“I can give you the answer to your question,” Daszak said.

“I’m going to answer it for you!” Griffith shot back, then outrageously accused Daszak of lying. Daszak didn’t get a chance to reply.

The whole session, more than three hours, went that way. The members kept peppering Daszak with questions about abstruse matters of science and the grant-making process, only to rudely cut him off when he tried to respond. They misquoted him to his face, misrepresented his work, and spouted cocksure inanities showing with every word that, scientifically speaking, they have no idea what they’re talking about.

Ideally, congressional hearings should be fact-finding efforts. This was nothing of the kind. It was an opportunity for posturing by politicians intent only on smearing Daszak and EcoHealth on the pretext of getting to the bottom of the pandemic’s cause.

How do we know this? From the fact that hours before the hearing even began, the subcommittee released a report calling on the National Institutes of Health and the Department of Health and Human Services to “immediately commence suspension and debarment proceedings against both EcoHealth and Dr. Daszak” — in other words, permanently cut them off from federal funding.

One more thing about this ludicrious cabaret act: The Democratic committee members, who should have been standing up for science and scientists, did the opposite by throwing Daszak under the bus.

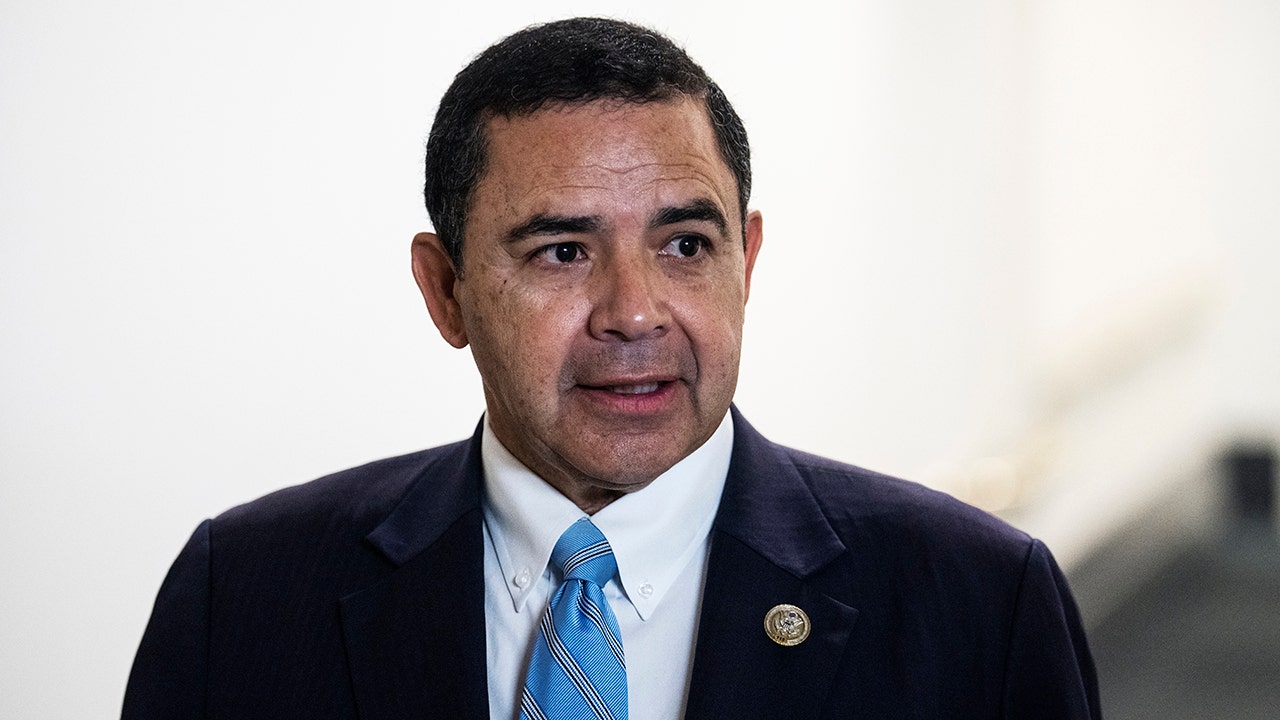

In his opening statement, Ranking Member Raul Ruiz (D-Indio), attacked the GOP majority’s preposterous position that the U.S. government funded research that created the virus responsible for COVID-19. But he accepted its position that Daszak “sought to deliberately mislead” government regulators.

Ruiz’s statement was echoed by other Democrats, including Rep. Debbie Dingell (D-Mich.). Perhaps they hoped that by allowing Daszak to be drawn and quartered, they might persuade the Republicans to climb down from their evidence-free claims about government complicity in the pandemic’s origins.

Their hearts didn’t seem to be in it, though; they talked as though their main concern was that EcoHealth was spending government funds. They all seemed to be reading from the same ChatGPT script, the key phrase of which was: “poor steward of the taxpayers’ dollars.” Nothing about EcoHealth’s significant achievements in public health.

That makes the Democrats’ performance all the more shameful and cowardly. They’re knowingly participating in a flagrantly fictitious smear campaign.

Let’s examine the background of this display of partisan grandstanding.

Fundamentally, it’s part of a disreputable campaign to demonize responsible scientists such as Anthony Fauci, who retired in 2022 as director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and was one of the most respected virologists and public health professionals in the world.

Republican leaders and the right wing have tried to turn Fauci into a sinister figure by advancing the absurd proposition that he somehow played a role in creating COVID-19 and spreading it worldwide, and that he masterminded the nation’s anti-pandemic policies, even though he had zero authority to do so.

This is no innocent game; it has subjected Fauci, who was a top pandemic advisor to Donald Trump until his resistance to Trump’s unhinged takes on the pandemic led to his being sidelined at the White House, to death threats and unending vilification on social media.

Daszak has come in for more than his share of character assassination. Social media posts referring to him have included the image of a guillotine. As the pandemic developed, Daszak told the committee in his opening statement Wednesday, “Our organization, staff, and even my own family were often targeted with false allegations, death threats, break-ins, media harassment, and other damaging acts.”

One recent post on X (formerly Twitter) said “the Daszak family should be shot down.” Daszak says he has asked X to cancel the abusive, anonymous account, without success.

What’s the purpose of this campaign? The attack on the credibility of science and scientists has arisen because validated scientific findings about global warming and the origins of COVID-19 cause economic and political discomfort to Big Business and know-nothings who believe that undermining science will advance their political careers. (I’m looking at you, Robert F. Kennedy Jr.)

An essential tenet of the right-wing position on COVID-19 is that the virus escaped from a Chinese laboratory, specifically the Wuhan Institute of Virology. Superficially this is an alluring theory, since the initial outbreak occurred at a wildlife market in that city. But there is absolutely not a speck of evidence for that theory, and scientific research overwhelmingly indicates that the virus reached humans via a spillover from infected wildlife — the path followed by countless viral outbreaks over human history.

Lab leak advocates love to point to a statement FBI Director Christopher Wray made in an interview with Fox News in March 2023 — that the bureau had concluded with “moderate confidence” that the virus had escaped from the Chinese lab. But he cited no evidence; the FBI’s assessment, which had been previously disclosed, had been part of a survey of all U.S. intelligence agencies that largely contradicted the FBI’s position. And in June, a report from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence refuted claims that the Chinese lab had played any role in the pandemic.

Anyway, the WIV isn’t exactly near the market — it’s miles away on the far side of the Yangtze River, in a city as densely populated as Los Angeles, with almost three times L.A.’s population, and a huge regional transportation and commercial hub.

That brings us back to EcoHealth, which was founded in 1971 and has long been an essential clearinghouse for funding for research into “emerging disease threats to the U.S.,” as Daszak said in his opening statement.

That has included providing funds for the WIV and other research in China, where viruses capable of jumping into the human population — as did SARS-CoV-2, the virus behind COVID-19 — are commonly found in bats, and where a vigorous, illicit trade in wildlife brings millions of humans into direct contact with potential disease carriers.

EcoHealth’s relationship with Chinese research institutions was open and aboveboard, and its funnelling U.S. grants to those institutions explicitly approved by the NIH and HHS.

EcoHealth was long considered a gold-plated research organization. “Their grants, when reviewed scientifically, scored at the highest levels in the scientific community,” says Gerald T. Keusch, a former associate director of international research at NIH. “The work they proposed was absolutely stunningly good.”

An internal memo prepared at NIH for a Fauci news conference in January 2020 described EcoHealth as one of “the biggest players in coronavirus work” and Daszak as one of “the world’s experts in … non-human coronaviruses” such as SARS-CoV-2.

As I’ve reported, EcoHealth’s useful and productive role in virological research began to unravel at a news conference April 17, 2020 when a reporter from a right-wing organization mentioned to then-President Trump that NIH had given a $3.7-million grant to the Wuhan Institute of Virology. (Actually, the WIV grant, which was channeled from a larger EcoHealth grant, was only $600,000).

Trump, sensing an opportunity to show a strong hand against China and advance his effort to blame the Chinese for the pandemic, responded: “We will end that grant very quickly.” The NIH terminated the full EcoHealth grant one week later prompting a backlash from the scientific community, including an open letter signed by 77 Nobel laureates who saw the action as a flagrantly partisan interference in government funding of scientific research.

The HHS inspector general found the termination to be “improper.” NIH reinstated the grant, but immediately suspended it until EcoHealth met several conditions that were manifestly beyond its capability, as they involved its demanding information from the Chinese government that it had no right to receive.

The EcoHealth grant was finally restored in May 2023. By then, EcoHealth no longer had a relationship with WIV, which had been barred from receiving any NIH funds. Still, at the time I celebrated the end of a Trump-inspired three-year shutdown of field work to examine how viruses move from rural wildlife to humans. Unfortunately, that was premature.

Since then, Daszak told me, NIH has continued to erect bureaucratic barriers preventing EcoHealth from accessing funds under the grant, in effect freezing its ability to work.

At Wednesday’s hearing, the GOP tried to pretend that the decision to terminate the grant was all NIH’s idea. “This was not ended by the president of the United States,” declared Mitchell Benzine, counsel to the subcommittee’s Republican majority.

Benzine has a suspiciously short memory. According to documents that the subcommittee itself made public, on Jan. 5 this year, Benzine himself elicited closed-door testimony from Lawrence Tabak, a top NIH official, that after that 2020 news conference “[Trump Chief of Staff] Mark Meadows called the Office of General Counsel at HHS, who then called Dr. Tabak, who then called Dr. [Michael] Lauer, who was instructed to cancel the grant.” Can’t get a much more direct line from Trump to NIH than that.

(Lauer is an NIH functionary who has been a key figure placing the bureaucreatic obstacle course before EcoHealth; my request for comment from him and Tabak was met with a no-comment from NIH.)

Wednesday’s hearing largely recapitulated the attacks on EcoHealth that have been floating in the right-wing fever swamp for four years now. They include a litany of minor bureaucratic snafus, such as a grant progress report that missed a deadline (Daszak said the problem was a glitch in an NIH web portal that prevented it from being submitted on time).

One key assertion is that EcoHealth was funding “gain of function” research at the Wuhan Institute. “Gain of function” is a widely misunderstood term that has become a shibboleth for proponents of the lab-leak hypothesis, who use it as an all-purpose symbol of sinister behavior, like “critical race theory” or “DEI” (diversity, equity and inclusion).

Technically speaking, gain-of-function is a method of modifying a pathogen in the lab to gauge its infectiousness in humans, the better to develop countermeasures such as vaccines. The right-wing claims that such research in China funded by NIH and EcoHealth created SARS-CoV-2, which then escaped into the wild.

There’s no evidence that the Wuhan lab did anything like that, and experienced virologists have questioned whether it’s even technically possible to have created the SARS2 virus given today’s level of knowledge. The U.S. government placed a moratorium on gain-of-function research from 2014 through 2017 to allow for the development of best-practice protocols.

NIH explicitly confirmed to EcoHealth that the studies it was funding didn’t qualify as gain-of-function under its own definition. That didn’t stop the committee members from wasting long swaths of their session accusing Daszak of secretly funding such experiments.

The attacks on EcoHealth appall scientists and public health experts who know that the organization’s work in identifying potential pandemic sources and crafting responses has never been more important. Agricultural authorities are dealing with the spread of a bird flu virus into cattle herds, another case of species-to-species, or zoonotic, viral transmission.

Given the bipartisan attacks against it, whether EcoHealth can avoid being cut off from all government funding is an open question. But that only underscores the supine irresponsibility with which Democrats have bought into the right wing’s attack on the organization and its crucial work.

“We now have zoonotic threats emerging at an accelerating cadence,” says Peter Hotez, a molecular virologist who is dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

“This is a time when we need to be doubling down and expanding our global virus surveillance networks,” Hotez told me. “By making up allegations, they’re undermining the work of EcoHealth and other organizations committed to understanding how viruses are jumping from animals to humans. We’re creating incredible vulnerability for ourselves. They’re damaging our national security. That to me is unforgivable — that they’re willing to jeopardize national security for political expedience.”

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoLarry Webb’s deathbed confession solves 2000 cold case murder of Susan and Natasha Carter, 10, whose remains were found hours after he died

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoHaiti Prime Minister Ariel Henry resigns, transitional council takes power

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoFirst cargo ship passes through new channel since Baltimore bridge collapse

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoSpanish PM Pedro Sanchez suspends public duties to 'reflect'

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoUS secretly sent long-range ATACMS weapons to Ukraine

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoHumane (2024) – Movie Review

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoAmerican Airlines passenger alleges discrimination over use of first-class restroom

-

Education1 week ago

Education1 week agoVideo: Johnson Condemns Pro-Palestinian Protests at Columbia University