Science

Florida professor lives in an underwater hotel for a record 73 days. His goal? An even 100

Joseph Dituri started his day like any other: with wires, test tubes and data — “basic science,” he says. He had his blood drawn, performed a pulmonary function test and took an electrocardiogram.

As he sat in the laboratory Wednesday near a stuffed animal of Dory, the forgetful blue fish of Disney-Pixar movie fame, several visitors swam up to wave hello.

How else would you expect to greet a man who calls himself “Dr. Deep Sea”?

Dituri, an associate professor of biomedical engineering at the University of South Florida, has lived since March 1 in a 100-square-foot laboratory within Jules’ Undersea Lodge, a hotel for scuba divers situated at the bottom of a 30-foot-deep lagoon in Key Largo, Fla.

A porthole allows Dituri to see plenty of fish and the occasional scuba diver.

(Joseph Dituri)

Divers exploring the area’s green waters periodically peek through his porthole window into the lab, which is about 8 feet wide. At night, the flashlights of divers and snorkelers sometimes shine through the circular window.

At 1:05 p.m. Eastern time last Saturday, Dituri broke the world record for longest time spent living in a fixed underwater habitat. The previous mark — 73 days, two hours and 34 minutes — was set in 2014 in the same lab by two professors from Tennessee, Bruce Cantrell and Jessica Fain.

(A Guinness World Records spokesperson says the organization is reviewing Dituri’s attempt.)

But Dituri, 55, isn’t on an aquatic adventure just to break records. He’s on a 100-day mission that combines medical testing and ocean research. The goal is to understand how being underwater can influence human health and to explore the ocean’s role in the treatment of disease.

The Marine Resources Development Foundation, which owns the lab, organized Dituri’s fact-finding mission, called Project Neptune.

The project requires daily experiments in physiology, with a medical team regularly diving to Dituri’s habitat to run tests that monitor his bodily response to long-term exposure to extreme pressure. The exams include submitting blood, urine and saliva samples, using electrocardiograms on his heart and electroencephalograms on his brain, and running pulmonary function exams. He’s also undergoing psychological and psychosocial tests so experts can study the impact of being in an isolated, confined environment for long periods of time.

Dituri, right, is a retired U.S. Navy saturation diver.

(Ben Norton / Brock Communications)

“We’re checking for human health, and what happens when you stuff a person in a tube for a little while,” Dituri said as another scuba diver swam up to the porthole.

Dituri has also been teaching classes online to students around the world, including in his biomedical engineering courses at the University of South Florida, hoping to encourage more students to pursue careers in science, technology, engineering and math.

“We have real serious problems to solve,” he said.

Scientists and others visit him regularly in the lab to talk about the research and how to preserve and protect the ocean.

Alongside the experiments and outreach, Dituri has learned how to cook a “solid” poached salmon in the microwave — the habitat’s partial pressure means he can’t use an open flame — and learned that crab legs might not be the best meal choice. “It stunk in this habitat for like five days,” he said. “There is no good turnover of air.”

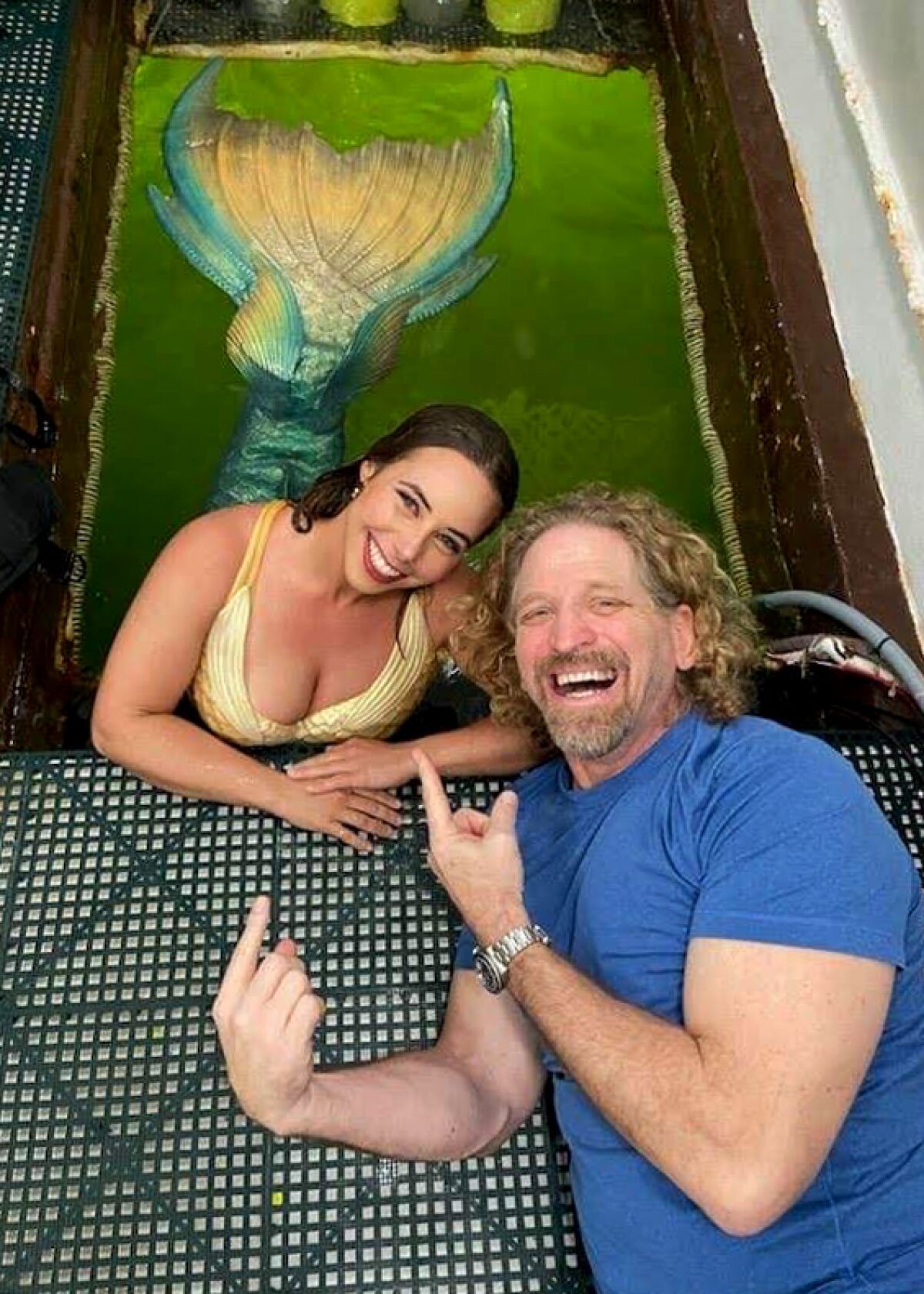

While living underwater, Dituri has had visitors — even one supposed mermaid.

(Joseph Dituri / Brock Communications)

He’s had a mermaid visit him, and spotted a seahorse on a recent scuba diving expedition.

“I had never seen one before, and I’ve been in the water for, I don’t know, 40 years,” said Dituri, a retired U.S. Navy saturation diver. (He was talking, of course, about the seahorse.)

He may have even inadvertently set another record by purchasing a new car while living underwater, which turned out to be trickier than he thought: Despite all of the planning and logistics he’d done, he forgot to bring his bank information under with him.

“It was one of those like last-minute scrambles,” Dituri said. (A Guinness World Records spokesperson said the organization does not monitor a record title for being the first to buy a car underwater.)

Dituri is expected to resurface on June 9 and undergo an in-depth medical examination by a team of doctors.

Once he’s above ground, he plans to go even higher by skydiving. But that one’s just for fun.

“I need to get the knees in the breeze,” he said.

Science

To save Black lives, panel urges regular mammograms for all women ages 40 to 74

To counteract growing rates of breast cancer in younger women and to reduce racial disparities in deaths, an influential panel has changed its advice and is urging most women to begin getting regular mammograms at age 40.

The new recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force say women without genetic mutations that make it extremely likely they will develop breast cancer should get their first mammogram to screen for the disease at age 40 and should continue with the exams every other year until they turn 74. The guidelines were published Tuesday in the Journal of the American Medical Assn.

Breast cancer is one of the most common cancers among women in the U.S., as well as one of the deadliest. An estimated 297,790 U.S. women were diagnosed with the disease last year, and 43,170 died of it, according to the American Cancer Society.

The task force, a group of 16 experts convened by the federal government, sparked an uproar 15 years ago when it said women could wait until 50 to begin regular, biennial breast cancer screening — much later and less frequent than what other medical groups were recommending at the time. The group’s rationale was that women in their 40s faced a low risk of breast cancer and that frequent testing of asymptomatic women in this age group caused too many to endure biopsies and other invasive procedures that were unnecessary and potentially dangerous.

The task force reaffirmed its controversial position in 2016. But when the time came to update its guidelines again, two facts stood out.

First, the incidence of invasive breast cancer in younger women, which had been slowly climbing since at least 2000, began to accelerate around 2015, rising by an average of 2% per year over the following four years.

Second, the task force recognized that among all racial and ethnic groups, Black women are most likely to be diagnosed with breast cancers that have progressed beyond stage 1, including the aggressive “triple negative” tumors that are particularly difficult to treat. Black women also have the highest mortality rate from breast cancer — about 40% higher than that of white women — “even when accounting for differences in age and stage at diagnosis,” the task force wrote in JAMA.

After analyzing data from randomized clinical trials and models based on real-world data, the panel determined that starting biennial mammograms at 40 instead of 50 would prevent an additional 1.3 breast cancer deaths per 1,000 women over the course of their screening lifetimes. For Black women, starting a decade earlier would avert an additional 1.8 deaths per 1,000 women.

“This is a big change, absolutely,” said Dr. Stamatia Destounis, chair of the American College of Radiology Commission on Breast Imaging. “We all realize that if you start to screen a woman at 40, you’re going to find the most cancers.”

Robert Smith, the American Cancer Society’s senior vice president for early cancer detection science, said the task force’s new guidance is more in line with advice from other medical organizations, including his own.

“We don’t want any woman to have a breast cancer diagnosed late if it can be avoided,” Smith said. “There’s no substitute for finding a breast cancer sooner in its natural history.”

But Ricki Fairley, founder and chief executive of Touch, the Black Breast Cancer Alliance in Annapolis, Md., said that if the goal is to reduce racial disparities, screening starting at age 40 isn’t nearly enough.

“I’m dealing with patients right now that are 24, 23, and are having breast cancer and dying,” said Fairley, a breast cancer survivor who was diagnosed at age 55. “Getting a first mammogram at age 40 is way too late for Black women.”

Reonna Berry, president and co-founder of the African American Breast Cancer Alliance in Minneapolis, criticized the task force for sticking with its advice to screen every other year.

“If we waited every two years to get a mammogram, a lot of Black women would be dead,” said Berry, who was diagnosed with breast cancer at 38 and again a few years ago, in her late 60s.

A radiologist reviews a mammogram at UCLA.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times)

The American College of Radiology and the Society of Breast Imaging recommend annual screening starting at 40. The American Cancer Society recommends annual screenings for 45- to 54-year-olds, then screening every year or two after that. In addition, the ACR advises Black women to conduct a risk assessment and devise a screening strategy with a doctor when they are 25, Destounis said.

Smith said that although Black women under 40 are more likely than their white counterparts to be diagnosed with breast cancer, the difference isn’t large enough to warrant widespread screening.

According to data gathered by the National Cancer Institute, there are 38 breast cancer cases per 100,000 Black women between the ages of 30 and 34, compared with 32.3 cases per 100,000 white women in the same age group. For women ages 35 to 39, the respective figures are 74.8 and 69.2. In both age groups, that amounts to fewer than 6 additional breast cancers per 100,000 women.

Smith and others criticized the task force for failing to endorse screening mammograms for women over 74. As in years past, the panel determined there wasn’t enough evidence to make a recommendation one way or another.

“At the age of 75, the risk of breast cancer is very high,” Smith said.

There are 473.2 cases per 100,000 women of all racial and ethnic backgrounds between the ages of 75 and 79, and 425.8 cases for ages 80 to 84, the National Cancer Institute reports.

“There’s no reason, at least in our judgment, that women should stop screening as long as they’re in good health and expect to live another 10 years,” Smith said.

Dr. John B. Wong, a vice chair of the task force, said the lack of evidence regarding mammograms for older women is “totally frustrating.”

There are no randomized clinical trials with women in this age group, but the panel did consider a cohort study of more than 1 million Medicare patients that found no benefit to screening women ages 75 to 84, Wong said.

The situation was similar regarding the use of ultrasound or MRI as supplemental screening tools for women with dense breasts, he said.

“We know that they’re at increased risk, and we know mammography doesn’t work as well for them,” Wong said. “We would love to have some evidence to help us decide what to recommend about what they should do.”

On the question of screening frequency, the task force had enough data to act. With biennial screening between the ages of 40 and 74, there will be about 1,376 false-positive results per 1,000 women over their lifetimes, along with 14 instances of doctors finding and treating early-stage tumors that might never have become dangerous if left alone. Both would increase by about 50% if women were screened annually, Wong said.

The panel concluded that screening every other year prevents more deaths and results in more years of life gained per mammogram, producing a better balance of benefits and harms.

Dr. Julie Gralow, chief medical officer for the American Society of Clinical Oncology, said she would weigh those trade-offs differently.

“As a breast cancer doctor, I’m on the receiving end of everybody who’s diagnosed, and I think they way overplayed the harms versus the benefits,” she said, particularly the anxiety that would stem from being asked to come in for follow-up imaging. “I know for some women that’s very scary and all, but it’s almost a paternalistic kind of view.”

That notion was echoed by Karen Eubanks Jackson, founder and CEO of Sisters Network, a national breast cancer organization for Black women.

“We understand that having too many mammograms can sometimes not be in your favor,” said Jackson, a breast cancer survivor. “But as a Black woman having had it four times, I’d rather be false positive than be positive and not know it. Give me my choice.”

Gralow emphasized that the task force recommendations do not apply to women with any kind of breast abnormality.

“If you have any symptom, then you should go straight to diagnostics, and that should be done at any age,” she said.

In Smith’s ideal world, precision medicine would allow doctors to replace broad guidelines with individualized screening recommendations based on the information in each woman’s health records.

“They might say, ‘Start screening at an earlier age’ or ‘Screen every year’ or ‘You can go every other year, and that’s just as safe,’ ” Smith said. “The sooner we move in that direction, the better.”

Science

Canny as a crocodile but dumber than a baboon — new research ponders T. rex's brain power

In December 2022, Vanderbilt University neuroscientist Suzana Herculano-Houzel published a paper that caused an uproar in the dinosaur world.

After analyzing previous research on fossilized dinosaur brain cavities and the neuron counts of birds and other related living animals, Herculano-Houzel extrapolated that the fearsome Tyrannosaurus rex may have had more than 3 billion neurons — more than a baboon.

As a result, she argued, the predators could have been smart enough to make and use tools and to form social cultures akin to those seen in present-day primates.

The original “Jurassic Park” film spooked audiences by imagining velociraptors smart enough to open doors. Herculano-Houzel’s paper described T. rex as essentially wily enough to sharpen their own shivs. The bold claims made headlines, and almost immediately attracted scrutiny and skepticism from paleontologists.

In a paper published Monday in “The Anatomical Record,” an international team of paleontologists, neuroscientists and behavioral scientists argue that Herculano-Houzel’s assumptions about brain cavity size and corresponding neuron counts were off-base.

True T. rex intelligence, the scientists say, was probably much closer to that of modern-day crocodiles than primates — a perfectly respectable amount of smarts for a therapod to have.

“What needs to be emphasized is that reptiles are certainly not as dim-witted as is commonly believed,” said Kai Caspar, a biologist at Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf and co-author of the paper. “So whereas there is no reason to assume that T. rex had primate-like habits, it was certainly a behaviorally sophisticated animal.”

Brain tissue doesn’t fossilize, and so researchers examine the shape and size of the brain cavity in fossilized dinosaur skulls to deduce what their brains may have been like.

In their analysis, the authors took issue with Herculano-Houzel’s assumption that dinosaur brains filled their skull cavities in a proportion similar to bird brains. Herculano-Houzel’s analysis posited that T. rex brains occupied most of their brain cavity, analogous to that of the modern-day ostrich.

But dinosaur brain cases more closely resemble those of modern-day reptiles like crocodiles, Caspar said. For animals like crocodiles, brain matter occupies only 30% to 50% of the brain cavity. Though brain size isn’t a perfect predictor of neuron numbers, a much smaller organ would have far fewer than the 3 billion neurons Herculano-Houzel projected.

“T. rex does come out as the biggest-brained big dinosaur we studied, and the biggest one not closely related to modern birds, but we couldn’t find the 2 to 3 billion neurons she found, even under our most generous estimates,” said co-author Thomas R. Holtz, Jr., a vertebrate paleontologist at University of Maryland, College Park.

What’s more, the research team argued, neuron counts aren’t an ideal indicator of an animal’s intelligence.

Giraffes have roughly the same number of neurons that crows and baboons have, Holtz pointed out, but they don’t use tools or display complex social behavior in the way those species do.

“Obviously in broad strokes you need more neurons to create more thoughts and memories and to solve problems,” Holtz said, but the sheer number of neurons an animal has can’t tell us how the animal will use them.

“Neuronal counts really are comparable to the storage capacity and active memory on your laptop, but cognition and behavior is more like the operating system,” he said. “Not all animal brains are running the same software.”

Based on CT scan reconstructions, the T. rex brain was probably “ a long tube that has very little in terms of the cortical expansion that you see in a primate or a modern bird,” said paleontologist Luis Chiappe, director of the Dinosaur Institute at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

“The argument that a T. Rex would have been as intelligent as a primate — no. That makes no sense to me,” said Chiappe, who was not involved in the study.

Like many paleontologists, Chiappe and his colleagues at the Dinosaur Institute were skeptical of Herculano-Houzel’s original conclusions. The new paper is more consistent with previous understandings of dinosaur anatomy and intelligence, he said.

“I am delighted to see that my simple study using solid data published by paleontologists opened the way for new studies,” Herculano-Houzel said in an email. “Readers should analyze the evidence and draw their own conclusions. That’s what science is about!”

When thinking about the inner life of T. rex, the most important takeaway is that reptilian intelligence is in fact more sophisticated than our species often assumes, scientists said.

“These animals engage in play, are capable of being trained, and even show excitement when they see their owners,” Holtz said. “What we found doesn’t mean that T. rex was a mindless automaton; but neither was it going to organize a Triceratops rodeo or pass down stories of the duckbill that was THAT BIG but got away.”

Science

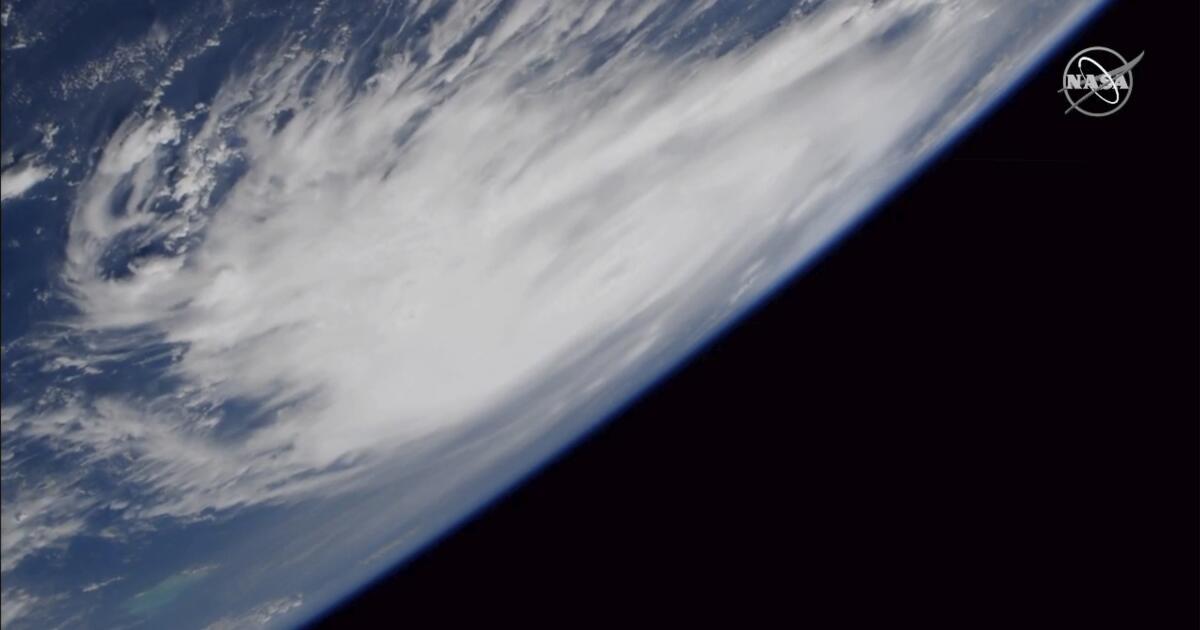

You're gonna need a bigger number: Scientists consider a Category 6 for mega-hurricane era

In 1973, the National Hurricane Center introduced the Saffir-Simpson scale, a five-category rating system that classified hurricanes by wind intensity.

At the bottom of the scale was Category 1, for storms with sustained winds of 74 to 95 mph. At the top was Category 5, for disasters with winds of 157 mph or more.

In the half-century since the scale’s debut, land and ocean temperatures have steadily risen as a result of greenhouse gas emissions. Hurricanes have become more intense, with stronger winds and heavier rainfall.

With catastrophic storms regularly blowing past the 157-mph threshold, some scientists argue, the Saffir-Simpson scale no longer adequately conveys the threat the biggest hurricanes present.

Earlier this year, two climate scientists published a paper that compared historical storm activity to a hypothetical version of the Saffir-Simpson scale that included a Category 6, for storms with sustained winds of 192 mph or more.

Of the 197 hurricanes classified as Category 5 from 1980 to 2021, five fit the description of a hypothetical Category 6 hurricane: Typhoon Haiyan in 2013, Hurricane Patricia in 2015, Typhoon Meranti in 2016, Typhoon Goni in 2020 and Typhoon Surigae in 2021.

Patricia, which made landfall near Jalisco, Mexico, in October 2015, is the most powerful tropical cyclone ever recorded in terms of maximum sustained winds. (While the paper looked at global storms, only storms in the Atlantic Ocean and the northern Pacific Ocean east of the International Date Line are officially ranked on the Saffir-Simpson scale. Other parts of the world use different classification systems.)

Though the storm had weakened to a Category 4 by the time it made landfall, its sustained winds over the Pacific Ocean hit 215 mph.

“That’s kind of incomprehensible,” said Michael F. Wehner, a senior scientist at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and co-author of the Category 6 paper. “That’s faster than a racing car in a straightaway. It’s a new and dangerous world.”

In their paper, which was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Wehner and co-author James P. Kossin of the University of Wisconsin–Madison did not explicitly call for the adoption of a Category 6, primarily because the scale is quickly being supplanted by other measurement tools that more accurately gauge the hazard of a specific storm.

“The Saffir-Simpson scale is not all that good for warning the public of the impending danger of a storm,” Wehner said.

The category scale measures only sustained wind speeds, which is just one of the threats a major storm presents. Of the 455 direct fatalities in the U.S. due to hurricanes from 2013 to 2023 — a figure that excludes deaths from 2017’s Hurricane Maria — less than 15% were caused by wind, National Hurricane Center director Mike Brennan said during a recent public meeting. The rest were caused by storm surges, flooding and rip tides.

The Saffir-Simpson scale is a relic of an earlier age in forecasting, Brennan said.

“Thirty years ago, that’s basically all we could tell you about a hurricane, is how strong it was right now. We couldn’t really tell you much about where it was going to go, or how strong it was going to be, or what the hazards were going to look like,” Brennan said during the meeting, which was organized by the American Meteorological Society. “We can tell people a lot more than that now.”

He confirmed the National Hurricane Center has no plans to introduce a Category 6, primarily because it is already trying “to not emphasize the scale very much,” Brennan said. Other meteorologists said that’s the right call.

“I don’t see the value in it at this time,” said Mark Bourassa, a meteorologist at Florida State University’s Center for Ocean-Atmospheric Prediction Studies. “There are other issues that could be better addressed, like the spatial extent of the storm and storm surge, that would convey more useful information [and] help with emergency management as well as individual people’s decisions.”

Simplistic as they are, Herbert Saffir and Robert Simpson’s categories are the first thing many people think of when they try to grasp the scale of a storm. In that sense, the scale’s persistence over the years helps people understand how much the climate has changed since its introduction.

“What the Saffir-Simpson scale is good for is quantifying, showing, that the most intense storms are becoming more intense because of climate change,” Wehner said. “It’s not like it used to be.”

-

Education1 week ago

Education1 week agoVideo: Dozens of Yale Students Arrested as Campus Protests Spread

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoEU sanctions extremist Israeli settlers over violence in the West Bank

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoShipping firms plead for UN help amid escalating Middle East conflict

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week ago'Nothing more backwards' than US funding Ukraine border security but not our own, conservatives say

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoDemocrats hold major 2024 advantage as House Republicans face further chaos, division

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoFetterman hammers 'a–hole' anti-Israel protesters, slams own party for response to Iranian attack: 'Crazy'

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoPeriod poverty still a problem within the EU despite tax breaks

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoA battle over 100 words: Judge tentatively siding with California AG over students' gender identification