Lifestyle

Tell NPR about the pandemic's impact on your high school years

Students at the University of Birmingham take part in their degree congregations as they graduate on July 14, 2009 in Birmingham, England.

Christopher Furlong/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Christopher Furlong/Getty Images

Students at the University of Birmingham take part in their degree congregations as they graduate on July 14, 2009 in Birmingham, England.

Christopher Furlong/Getty Images

High school seniors across the country are preparing to graduate — with the class of 2024 having started their freshman year during the beginning of the pandemic in 2020.

And Morning Edition would like to know how the pandemic impacted your life and your studies as a member of the class of 2024.

With your responses, please tell us your first and last name, age and where you’re from. You can also share your answers as an audio submission.

Your answers could be used on air or online.

We will be accepting responses until 12:00 p.m. ET on May 6.

Your submission will be governed by our general Terms of Use and Privacy Policy. As the Privacy Policy says, we want you to be aware that there may be circumstances in which the exemptions provided under law for journalistic activities or freedom of expression may override privacy rights you might otherwise have.

Lifestyle

A German novel about a tortured love affair wins 2024 International Booker Prize

Author Jenny Erpenbeck’s novel Kairos was named this year’s winner of the International Booker Prize.

Thomas Lohnes/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Thomas Lohnes/Getty Images

Author Jenny Erpenbeck’s novel Kairos was named this year’s winner of the International Booker Prize.

Thomas Lohnes/Getty Images

Kairos, a novel about a love affair between a younger woman and older man in 1980s Germany, has won this year’s International Booker Prize. The award is one of the most prestigious prizes for fiction translated into English.

The book, originally written in German by Jenny Erpenbeck, was translated by Michael Hofmann. The two will receive a prize of 50,000 British pounds (about $63,000), split evenly.

At the center of Kairos is a relationship between 19-year-old Katherina, and Hans, a married writer in his 50s. They have sex, they go on walks, they listen to music. But the relationship soon starts to turn violent and cruel. This feeling of loss and disillusionment maps onto the political shifts happening in Germany at the time. In praising the novel, Fresh Air critic John Powers writes that “Erpenbeck understands that great love stories must be about more than just love.”

He continues: “Even as she chronicles Katharina’s and Hans’ romance in all its painful details, their love affair becomes something of a metaphor for East Germany, which began in hopes for a radiant future and ended up in pettiness, accusation, punishment and failure.”

Erpenbeck was previously an opera director. Her first novel was 2008’s The Old Child and The Book of Words about a child who loses her memory. In 2018, she was shortlisted for the International Booker Prize for her novel Go, Went, Gone. She’s a hugely acclaimed writer earning glowing reviews and glossy profiles from NPR, The New York Times, and The New Yorker, with critics often predicting a Nobel Prize win in her future.

Translator Michael Hofmann is a poet, essayist, and a previous judge for the International Booker Prize. Hofmann is the first male translator to win the award. He’s translated dozens of books from German to English, including authors such as Franz Kafka and Hans Fallada. A 2016 interview in The Guardian noted his ability to “single-handedly revive an author’s reputation,” calling him “arguably the world’s most influential translator of German into English.”

In a press release announcing the prize, Eleanor Watchel, chair of this year’s judge, praised the way the novel used the personal story as a way of examining the broader political machinations of Germany. “The self-absorption of the lovers, their descent into a destructive vortex, remains connected to the larger history of East Germany during this period, often meeting history at odd angles.”

The other finalists for the 2024 International Booker Prize were Not a River by Selva Almada, translated from Spanish by Annie McDermott; Crooked Plow by Itamar Viera Junior, translated from Portuguese by Johnny Lorenz; Mater 2-10 by Hwang Sok-yong, translated from Korean by Sora Kim-Russell and Youngjae Josephine Bae; What I’d Rather Not Think About by Jente Posthuma, translated from Dutch by Sarah Timmer Harvey; and The Details by la Genberg, translated from Swedish by Kira Josefsson.

Author Georgi Gospodinov and translator Angela Rodel won last year’s International Booker Prize for the novel Time Shelter.

This story was edited for radio and digital by Meghan Collins Sullivan.

Lifestyle

Chef Andrew Zimmern Slams New Ozempic-Inspired Frozen Food Lines

TMZ.com

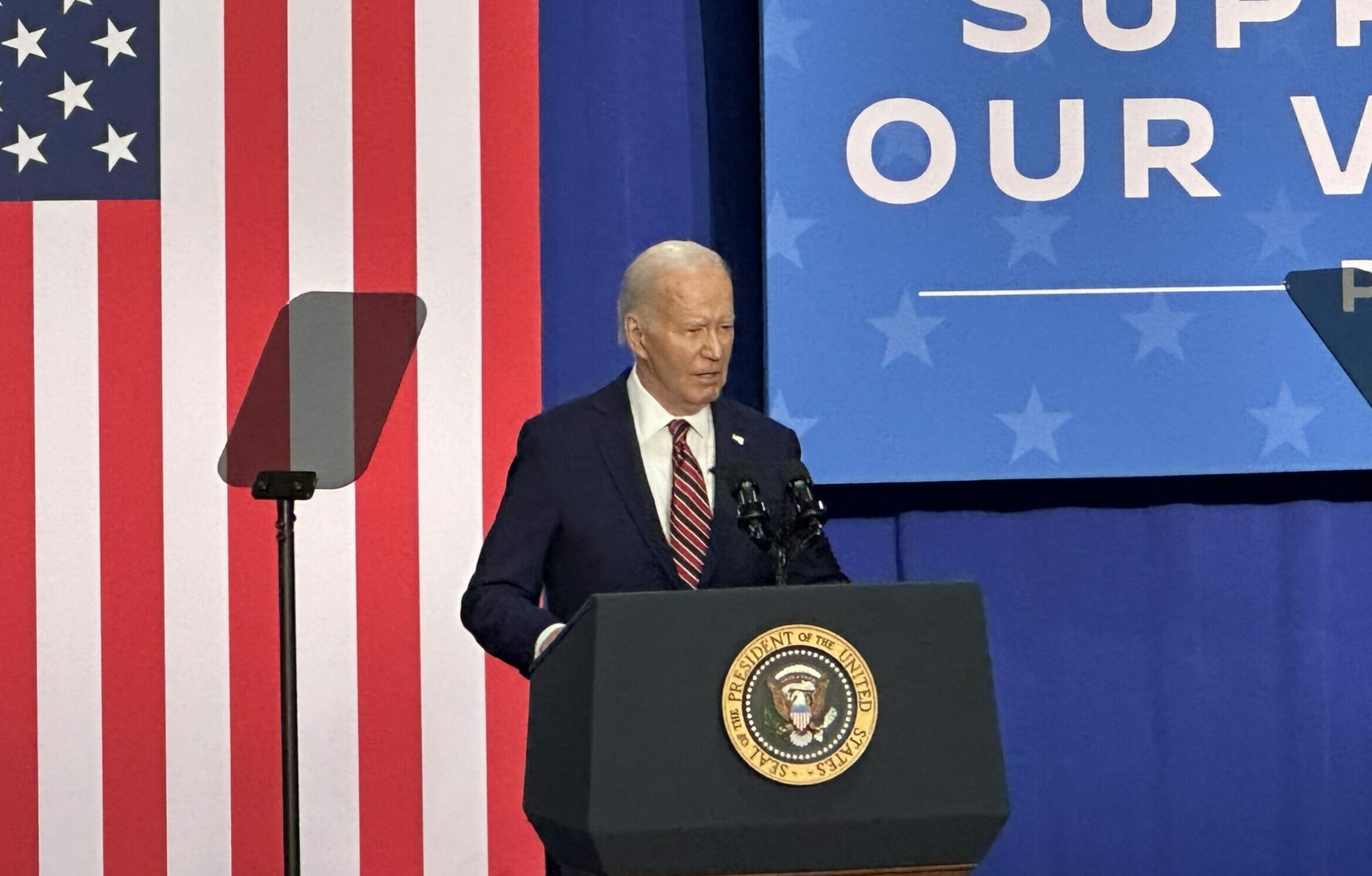

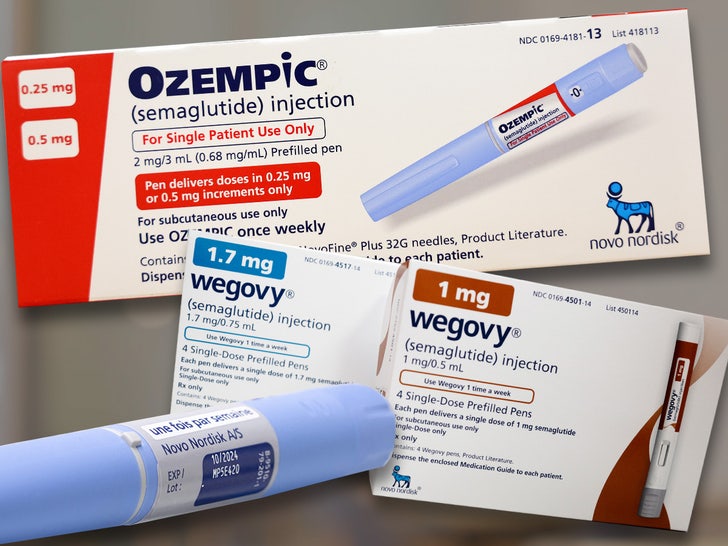

Chef Andrew Zimmern is slamming the food industry for creating Ozempic-friendly meals … as processed foods are largely to blame for America’s obesity epidemic.

We caught up with the celebrity chef Tuesday at LAX, where he made it clear he isn’t against people using weight loss medications — but finds it “about as messed up as it gets” that businesses are capitalizing on the situation.

As more and more Americans get on board with weight loss meds like Ozempic or Wegovy, the “Bizarre Foods: Delicious Destinations” host says .. “I think the really sad truth is we’re gonna have more processed food that costs $5 or less to go with your very expensive injectable.”

Waiting for your permission to load the Instagram Media.

Chef Andrew encouraged people to use common sense … advising fans to catch some sleep and put in the work to stay active — whether in a gym or outside — and he says that’s what will really make a difference, health-wise.

Now, the TV personality didn’t call out any particular company by name — but his criticism comes on the heels of Nestlé announcing a new frozen food line to be consumed while on weight loss meds.

The new line features 12 portion-controlled meals high in protein and fiber.

While the brand’s full lineup has yet to be announced, it did confirm it would be in stores this year with pricing at $4.99 or less. Sooo … Andrew nailed that!

Though we can’t say we’re surprised by the food line news, especially since celebs like Oprah Winfrey, Whoopi Goldberg, Tracy Morgan and Kelly Clarkson have all admitted to using weight loss medication.

For folks sticking with the old-fashioned eating well and exercising … Andrew shared some new research.

Lifestyle

Prize-winning Bulgarian writer brings 'The Physics of Sorrow' to U.S. readers

Bulgarian writer Georgi Gospodinov won the 2023 International Booker Prize for his book, Time Shelter. An English version of The Physics of Sorrow, an earlier novel, has just been published in the United States.

Toward the end of this brilliant book, Gospodinov considers the concept of “weight” in physics. He writes, “The past, sorrow, literature — only these three weightless whales interest me.” This complex sentence provides a summation of Gospodinov’s fascinating literary explorations.

Elegantly translated by Angela Rodel, The Physics of Sorrow is a fragmented novel that coheres into a remarkable, thought-provoking whole. It is a winding labyrinth through Bulgarian communism, art, literature, history, the personal past, love, sorrow, and so much more.

In epigraphs, Gospodinov invokes Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges and Portuguese writer Fernando Pessoa, members of the tradition in which Gospodinov writes. At the same time, he quotes St. Augustine, Gustave Flaubert, and his own fictional character Gaustine, signaling to readers not to take anything too seriously, but also to consider the weight of each word.

Gospodinov frames his novel around the myth of the Minotaur, a monster with a bull’s head and a man’s body, captive in an underground Labyrinth on Crete. There are multiple variations of the myth, and multiple explanations of how the Minotaur came into being. Gospodinov parses through many of them, like a gourmet cook selecting produce. He considers how aspects of this myth are imprinted on modernity — man behaving as beast and society “othering” those who are different.

Gospodinov’s narration is fluid. Sometimes he writes in first person, sometimes a boy/man named Georgi (like the author) narrates, sometimes the narration is in third person. We get insights into Gospodinov’s reading and writing life. “At five I learned to read, by six it was already an illness … literary bulimia.” He leaves a blank space on a page, saying it was written with invisible fruit ink. “What, so you don’t see anything? …If only I could write a whole novel in such ink.”

If there is a plot, it is composed of the arcs of several lives, including a person like the author himself and a person who may be like his grandfather. We get characters’ memories from World War I, and World War II, which could be Gospodinov’s own family stories.

The Physics of Sorrow, however, is not a novel to read for plot. It is a book that raises vexing questions about the human condition, and travels down labyrinthine digressions about topics that consume us — life, death, social woes, war, peace, old age, youth. And perhaps the creation of literature, above all.

For Gospodinov, time is an artifice. Present, past, and future slide around like pieces on a chessboard. A section called “The Chiffonier of Memory,” exemplifies Gospodinov’s technique. Here, the narrator — perhaps the author — is a journalist writing about Bulgarian WWII cemeteries. He travels through Serbia on the roads his grandfather “trudged on foot through the mud in the winter of 1944,” before stopping in Harkány, Hungary to interview a man who lives in a house where his grandfather was billeted during the war.

The man comments on his mother, an old woman present at the interview, as an occasion to explore memory: “Her memory is a chiffonier, I can sense her opening the long locked-up drawers … she has to wade through more than fifty years, after all.”

The man is ill at ease with his mother’s silence. He asks her something. “She turns her head slightly, without taking her eyes off me [the narrator]. It could pass as a tick, a negative response, or part of her own internal monologue.” The man notes that since his mother had a stroke, her memory is not all there.

But the narrator is having a different experience. He ignores his interviewee’s comments, certain that the woman recognizes him because he looks just like his grandfather.

The narrator jumps through time to describe how beautiful this woman was as a young woman, and how much his grandfather loved her. Even though the narrator was not there, he describes what she looked like and what she wore, projecting his grandfather’s love affair — which may or may not have happened — as his own.

Even though the narrator and the old woman have “no language in which we can share everything,” her eyes say in “impeccable Bulgarian: hello, thank you, bread, wine … I continue in Hungarian: szép (beautiful) … as if passing a secret message from my dead grandfather.”

Who has actually experienced this love affair and who is the narrator? The passage may read as linear story, until the reader stops to consider the enormous gap between the time of the interview and the time of the love affair.

The book purports to be about sorrow, and it is. Sorrow laces through life in many guises — grief, abandonment, regret, guilt. For this reader, Gospodinov’s multi-faceted considerations of human (and mythical) sorrow are reason enough to read the book.

At one point, Gospodinov writes that he aspires to “keep a precise catalogue of everything.” It feels like he has nearly succeeded with this innovative, captivating novel.

Martha Anne Toll is a DC based writer and reviewer. Her debut novel, Three Muses, won the Petrichor Prize for Finely Crafted Fiction and was shortlisted for the Gotham Book Prize. Her second novel, Duet for One, is due out May 2025.

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoSkeletal remains found almost 40 years ago identified as woman who disappeared in 1968

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoIndia Lok Sabha election 2024 Phase 4: Who votes and what’s at stake?

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoUkraine’s military chief admits ‘difficult situation’ in Kharkiv region

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoAavesham Movie Review

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoTrump, Reciting Songs And Praising Cannibals, Draws Yawns And Raises Eyebrows

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoUnfrosted Movie Review: A sweet origins film which borders on the saccharine

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoCatalans vote in crucial regional election for the separatist movement

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoNorth Dakota gov, former presidential candidate Doug Burgum front and center at Trump New Jersey rally