Health

Dr. Susan Love, Surgeon and Breast Health Advocate, Dies at 75

“I started to realize how women weren’t getting information,” Dr. Love told People. “If they came in with a lump or what they thought was a lump, the doctor would say, ‘Don’t worry your little head about that, dear.’ Most of these patients were scared to death. I realized I could make a contribution.”

Dr. Love became an assistant clinical professor of surgery at Harvard in 1987. The next year she founded the Faulkner Breast Center, a Boston clinic whose medical staff was almost entirely female.

In 1992, she joined the David Geffen School of Medicine at U.C.L.A. and established a clinic, the U.C.L.A. Breast Center, which she directed. (Now known as the Revlon/U.C.L.A. Breast Center, it is a hub for treatment and research.)

Over time, Dr. Love’s teeming schedule of interviews and public appearances, and the absences they involved, caused tension among colleagues at the breast center. She resigned from the center in 1996, though she continued to teach part time at U.C.L.A., where at her death she was a volunteer clinical professor.

Dr. Love became associated with the Santa Barbara Breast Cancer Institute, a research center, in the mid-1990s. Now based in Santa Monica, Calif., it was renamed after Dr. Love in 2004.

The foundation’s projects include the Love Research Army (formerly the Love/Avon Army of Women), an initiative begun by Dr. Love that recruits volunteers from around the world to participate in breast-cancer studies; to date, more than 360,000 people have enrolled, including some men interested in learning about the disease.

Dr. Love is survived by her wife, Dr. Helen Sperry Cooksey, a surgeon, whom she married in San Francisco in 2004 during the brief period when same-sex marriages were being performed there, before a California ballot proposition made them illegal in 2008. Also surviving is their daughter, Katie Patton-LoveCooksey, whose adoption by her two mothers in 1993 — Dr. Love was the biological mother; both women reared her from birth — was the first granted to a same-sex couple in Massachusetts. In addition, Dr. Love is survived by two sisters, Christine Adcock and Elizabeth Love, and a brother, Michael James Love.

Health

Here’s Why You’re Gaining Weight and How to Shed Those Pounds

Use left and right arrow keys to navigate between menu items.

Use escape to exit the menu.

Sign Up

Create a free account to access exclusive content, play games, solve puzzles, test your pop-culture knowledge and receive special offers.

Already have an account? Login

Health

Medical test linked to cancer, plus rising strep throat cases

Fox News’ Health newsletter brings you stories on the latest developments in healthcare, wellness, diseases, mental health and more.

TOP 3:

– Common medical procedure linked to 5% of cancers

– Invasive strep throat strain has more than doubled in US

– Diabetes risk linked to these food combinations

This week’s top health stories explored risks of common medical tests, food and drink combinations that increase diabetes risk, and a surge in strep throat cases. (iStock)

MORE IN HEALTH

‘DECADES YOUNGER’ – A U.S. senator says diabetes and weight-loss drugs changed his life. Continue reading…

FOUNTAIN OF YOUTH? – Anti-aging benefits linked to one surprising health habit. Continue reading…

TRAINING TOOLKIT – Check out these 10 tools to help with marathon prep and recovery. Continue reading…

FOLLOW FOX NEWS ON SOCIAL MEDIA

YouTube

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTERS

Fox News First

Fox News Opinion

Fox News Lifestyle

Fox News Health

Fox News Autos

Fox News Entertainment (FOX411)

DOWNLOAD OUR APPS

Fox News

Fox Business

Fox Weather

Fox Sports

Tubi

WATCH FOX NEWS ONLINE

Fox News Go

STREAM FOX NATION

Fox Nation

Health

What to Know About Today’s Meth

The highly addictive drug, manufactured almost exclusively by Mexican cartels, is more dangerous than ever. Its use has been surging across the country. Unlike fentanyl, there are no medicines that can swiftly reverse a meth overdose and none approved to treat meth addiction.

-

News1 week ago

News1 week ago3 Are Killed in Shooting Near Fredericksburg, Va., Authorities Say

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoFilm Review: 'Warfare' is an Immersive and Intense Combat Experience – Awards Radar

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoMen’s NCAA Championship 2025: What to know about Florida, Houston

-

Health1 week ago

Health1 week agoAs RFK Jr. Champions Chronic Disease Prevention, Key Research Is Cut

-

Politics1 week ago

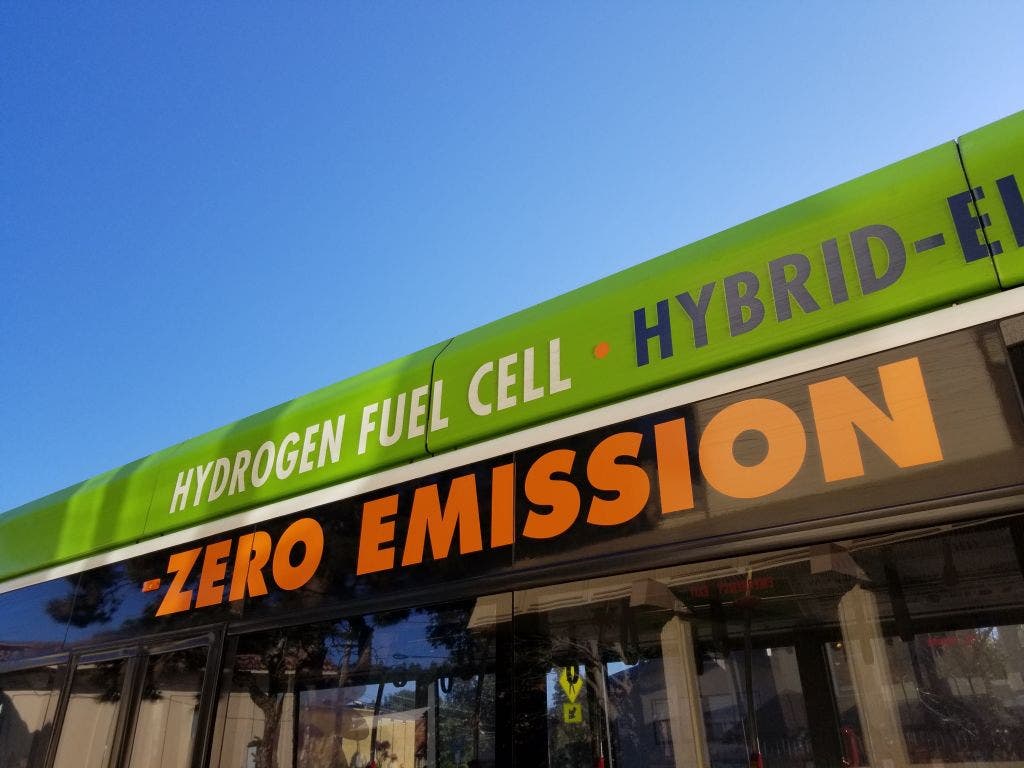

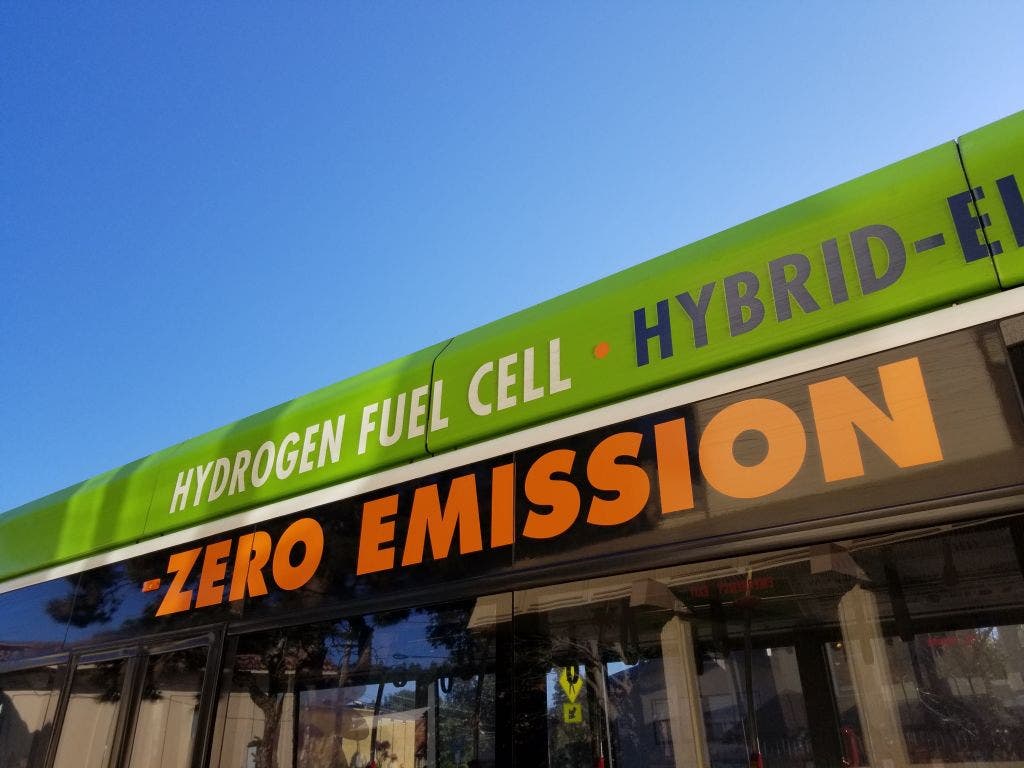

Politics1 week agoH2Go: How experts, industry leaders say US hydrogen is fuel for the future of agriculture, energy, security

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoBoris Johnson Has Run-In With Feisty Ostrich During Texas Trip

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoEPP boss Weber fells 'privileged' to be targeted by billboard campaign

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoMeta got caught gaming AI benchmarks