Entertainment

A look into the decade that defined Brian De Palma could use more critical consideration

Fall Preview Books

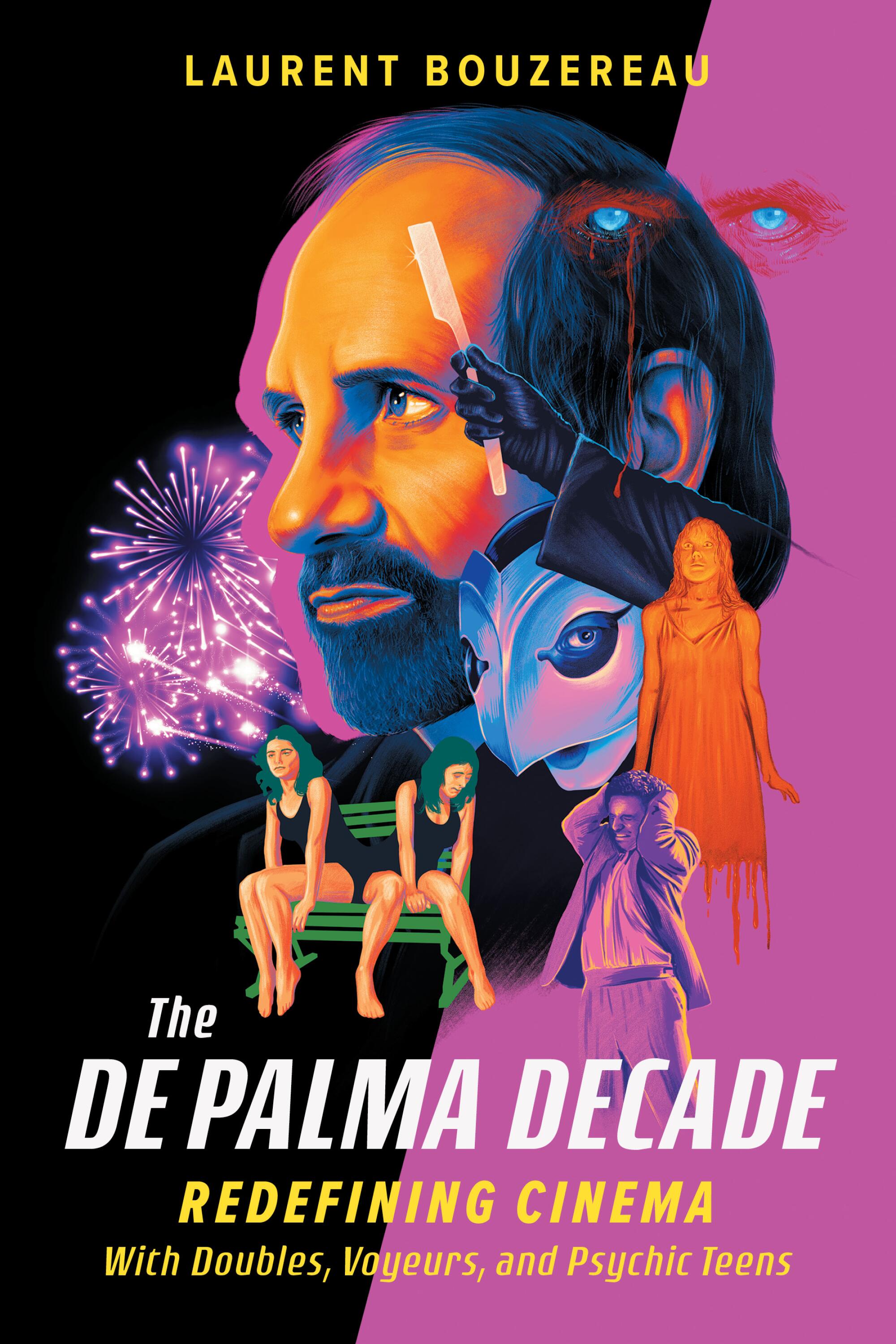

The De Palma Decade

By Laurent Bouzereau

Running Press: 320 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Martin Scorsese made his name in the 1970s with dramas about characters living on the fringes of society. Francis Ford Coppola, seeking his own personal projects, almost reluctantly struck paydirt with the first two “Godfather” movies. George Lucas, of course, wrote and directed “Star Wars.” But none had a stranger, more expressive decade than Brian De Palma. With a string of sensational, graphic thrillers and horror movies, including “Sisters” (1972), “Carrie” (1976), “The Fury” (1978) and “Dressed to Kill” (1980), De Palma created his own film language — gory and operatic, kinky and depraved, laden with optical effects (find someone who looks at you the way De Palma looks at a split screen) and often comically indebted to Alfred Hitchcock. Many moviegoers loathe De Palma. Many more love him. But very few find him boring.

And yet, “The De Palma Decade,” the new book out now by author and filmmaker Laurent Bouzereau, somehow makes him seem just that. This is less a critical consideration or biography so much as, to borrow the title of the unnerving Frederick Exley novel, a fan’s notes. Bouzereau, who made the recent (and excellent) Faye Dunaway documentary, “Faye,” really, really likes De Palma. He refers to a scene in “Sisters” as “pure cinematic genius.” Michael Caine’s performance as the transgender psychiatrist/murderer in “Dressed to Kill” is “predictably amazing and daring”; that film’s intricately constructed cat-and-mouse seduction sequence at the Metropolitan Museum of Art — the interiors were actually shot at the Philadelphia Museum of Art — is “simply mesmerizing and bewitching.” John Farris’ source novel for “The Fury” is “fascinating.” Even more, er, fascinating is that such anodyne language can be used to describe a filmmaker who has always been determined to jolt the viewer out of any sense of complacency.

“The De Palma Decade” unfolds as a series of oral histories plus copious plot summary, featuring interviews with De Palma — or, as Bouzereau refers to him near the book’s beginning, “Brian” — and an array of his cast and crew members through the years. Walking through these pages you’ll find the likes of Amy Irving (“Carrie,” “The Fury”), film editor Paul Hirsch (who won an Oscar for cutting “Star Wars”) and Chicago theater veteran Dennis Franz, who, as De Palma devotees know, warmed up for his signature work in “Hill Street Blues” and “NYPD Blue” by playing cops in “The Fury” and, most delightfully, “Dressed to Kill.”

Bouzereau did some reporting, and some of his subjects actually have something to say. De Palma talks about the importance of music in setting the tone for his long, dialogue-free scenes (like that museum sequence). Hirsch riffs on the different approaches taken by “The Fury” stars Kirk Douglas and John Cassavetes: Douglas, who attacked his role with vim, came in hot but fizzled in later takes, while it took Cassavetes, who often booked acting jobs to help pay for the movies he wanted to make himself, about 10 takes to get loose. Nestled between the platitudes of “The De Palma Decade” are some genuine insights into the filmmaking process.

But the author’s unabashed adoration of De Palma can be a hindrance to deeper understanding. Bouzereau touches on the primary controversy surrounding “Dressed to Kill,” that “De Palma conflates transness with mental illness and homicidal behavior.” Caine’s character does indeed come across as a trans person whose conflicted identity leads him to kill. Here we go. Bouzereau is going to ask his hero how he views all of this now. And then … he doesn’t. Instead, De Palma says a little about how his screenplay for “Cruising,” a movie ultimately written and directed by William Friedkin, led to some of his ideas for “Dressed to Kill.” With that, the author lets him skate, onto the next platitude. Early on, Bouzereau writes that he has “no intention here to make a social treaty or statement or defend the controversial aspects of De Palma’s work” (perhaps he means “treatise,” not “treaty”). Fair enough. But the idea of handling such a gleeful provocateur with kid gloves seems to somehow miss the point of De Palma’s work.

Laurent Bouzereau’s unabashed adoration of Brian De Palma can be a hindrance to deeper understanding.

(Travers Jacobs)

The book covers seven films, organized thematically into three sections: The Split (“Sisters” and “Dressed to Kill”), The Power (“Carrie” and “The Fury”) and The Tragedies (“Phantom of the Paradise,” “Obsession” and “Blow Out”). “The Split,” of course, has multiple meanings for De Palma, who used split screens not merely as an aesthetic exercise: Like many an artist of the macabre, going back at least to Edgar Allan Poe, he also made bloody hay out of the theme of doubling, and the terror and instability inherent to the idea of a divided self.

By the time he made “Sisters,” in 1972, De Palma had already done a few scrappy counterculture features, including “Greetings” (1968), “The Wedding Party” (1969) and “Hi, Mom!” (1970). But “Sisters,” a proper freakout starring Margot Kidder, playing conjoined twins, is the first of what we now think of as a De Palma movie: a psychosexual nightmare with madman instincts. Viewed with the hindsight of 52 years, it feels of a piece with other rule-breaking, devil-may-care horror films of the period, including George Romero’s “Night of the Living Dead” (1968), Wes Craven’s “The Last House on the Left” (1972) and David Cronenberg’s “Shivers” (1975).

It is, in other words, the real deal. Paradoxically, it also marks De Palma’s true entry into the sincerest form of flattery, the imitation game. Bouzereau starts his defense early, asking, “Is it fair to label De Palma a copycat? Isn’t he, rather, the legitimate heir to the Hitchcock kingdom?” He may, in fact, be both.

Angie Dickinson is trapped in an elevator by a psychotic killer in director Brian De Palma’s 1980 movie “Dressed to Kill.”

(Filmways Pictures)

De Palma’s slavish emulation of Hitchcock runs through numerous films, and with notable specificity. Someone witnesses a murder in the apartment across the way, a la “Rear Window” (“Sisters,” “Body Double”). A blond star is murdered in a movie’s first act, as in “Psycho” (“Dressed to Kill,” which also throws in a couple of shower scenes and an obtuse expert explaining why a man dresses as a woman). He bows to “Vertigo” on multiple occasions, including “Blow Out” (man suffers the same tragedy twice, unable to prevent murders he has indirectly enabled) and, more directly, “Obsession,” about a grief-stricken man who reconstructs a lost lover. In these movies De Palma is almost like a hip-hop producer, mixing samples of different songs to create a new whole. He is director as collagist.

By focusing on De Palma’s ‘70s output (“Blow Out” and “Dressed to Kill” are technically early-‘80s movies, but exact decades can be imprecise markers of an artist’s thematic output), the book opts to pull up short of the director’s next, in many ways more eclectic, period. The ‘80s brought, among others, the opulence of “Scarface” (the subject of a pair of recent books, by Glenn Kenny and Nat Segaloff), the undiluted sleaze of “Body Double,” the mainstream success of “The Untouchables” and the underrecognized Vietnam War drama “Casualties of War.” If you seek a more comprehensive study, check out Noah Baumbach and Jake Paltrow’s fine 2015 documentary “De Palma.” In “The De Palma Decade,” the filmmaker gets a more precise spotlight. And he couldn’t have asked for a more devoted fan to shine it.

Movie Reviews

Vishnu Vinyasam Movie Review – Gulte

2.5/5

01 Hrs 59 Mins | Romantic Comedy | 27-02-2026

Cast – Sree Vishnu, Nayana Sarika, Satya, Brahmaji, Praveen, Murali Sharma, Srikanth Iyyengar, Satyam Rajesh, Srinivasa Reddy, Goparaju Ramana and others

Director – Yadunaath Maruthi Rao

Producer – Sumanth Naidu G

Banner – Sree Subrahmanyeshwara Cinemas

Music – Radhan

Since 2023, with three commercial hits and one critically acclaimed film, Sree Vishnu has established himself as a minimum guarantee hero and built a loyal audience. To continue the success streak, he chose yet another romantic comedy film, directed by debutant Yadunaath Maruthi Rao. ‘Aay’ fame, Nayana Sarika, played the female lead role and Radhan, scored the music for the film. After creating enough curiosity among the audience with the teaser and trailer, the film was finally released in theatres today. Did Sree Vishnu, deliver yet another hit with a romantic comedy film? Did Nayan Sarika, score a hit in Telugu, after AAY & KA? How does the debutant director, Yadunaath Maruthi Rao, do? Did the music director, Radhan, come up with memorable songs and score? Let’s figure it out with a detailed analysis.

What is it about?

Vishnu(Sree Vishnu), works as a junior lecturer at a college, where Manisha(Nayan Sarika), works as the head of the department(HOD/faculty). Manisha, with her eccentric characteristics, intrigues Vishnu and both of them eventually fall in love with each other. When everything is going well for the couple to get married, Manisha informs Vishnu about a flaw in her Jathakam. What was the Dosham(flaw) in Manisha’s jathakam? How did it impact her prospects of getting married before meeting, Vishnu? Why did Vishnu initially get reluctant to marry Manisha, after hearing about her Jathaka Dosham? Will the couple sort out all the issues and get married eventually? Forms the rest of the story.

Performances:

Sree Vishnu, with his comedy timing generated a few fun moments that worked in favour of the film. However, in an attempt to appear effortless, he went overboard at times and appeared monotonous at a few places. Nayana Sarika got a good role and she delivered a good performance. She looked good throughout the film and appeared confident.

Satya, got a full-length role and he was able to generate a few laughs here and there with his comedy timing. Srikanth Iyyengar’s performance looked over the top and his portions looked rushed and very artificial. Srinivasa Reddy played a role similar to Mallikarjuna Rao’s role in Raviteja’s movie, Venky. He did an ok job but it seemed like he did dub for his role in the film? The film had Brahmaji, Praveen, Murali Sharma, Satyam Rajesh, Goparaju Ramana and a few others, in character roles. All of them made their presence felt but none of their roles gave the desired impact and extra mileage.

Technicalities:

Cinematography by Sai Sriram, is a major plus to the film. The visuals looked colourful, vibrant and gave a pleasant look to the film throughout. Radhan’s music should have been better. The songs scored by him were below par and the background score was pretty standard. Editing by Karthikeyan Rohini, was alright. He tried to cut the film with a very crisp runtime of around two hours and yet, ended up having a few repetitive sequences. Production values by, Sree Subrahmanyeshwara Cinemas, were decent and were within the limitations of a midrange romantic comedy film. Let’s discuss the work of the writer and the director, Yadunaath Maruthi Rao, in detail in the analysis section.

Positives:

1. First Half

2. Comedy Portions

3. Sree Vishnu & Satya’s Timing

4. Cinematography

Negatives:

1. Second Half

2. Lack of Strong Emotions

3. Music

Analysis:

The debutant writer and the director, Yadunaath Maruthi Rao, wrote a so-called peculiar characterisation of the female lead in the film and tried to generate enough fun moments using the comedy timing of his lead actor, Sree Vishnu and the lead comedian, Satya. Right from the word go, the writer intended only to make the audience laugh at any cost, and in doing so, he succeeded in parts but would have done a better job in other parts, especially the latter part of the second half. The film had at least five to six notable actors but for some reason, the director only concentrated on generating fun by using his lead actor.

The entire first half of the film unfolded without any major complaints. There were enough comedy sequences in the first half that engaged the audience in a fairly decent manner and the revelation of the conflict point during intermission, worked as well. However, after the initial few minutes of the second half, the film got into repetitive mode and the drama during the last thirty minutes was the film was written and executed in a very unexciting manner without any proper emotional depth. The twist during the climax was very predictable and it was narrated in a bland and rushed manner. Better care in writing and execution during the second half would have elevated the film’s overall graph.

The bare minimum that the audience expects from debutant writers and directors is original characters and characterisations, isn’t it? In Vishnu Vinyasam, to a crucial character, it was surprising to see a debutant director use the characterisation of ‘Jagadamba Chowdary’, a character from Ravi Teja’s movie Venky. Also, at just around two hours of runtime, the film makes the audience feel monotonous with a few repetitive sequences. One of the major negative points of the film is the songs. For a romantic comedy film to work, it is necessary to have at least one or two chartbuster songs. Unfortunately, none of the songs composed by, Radhan, helped the film in any way.

Overall, the core point of, Vishnu Vinyasam, has enough potential to become a very engaging romantic drama film. But, the half-hearted effort from the writer, director and the music director, ended up making it a decent watch. You may give it a try watching for a few well-executed comedy portions, Sree Vishnu and Satya’s timing.

Final Verdict – Partly Entertaining

Rating – 2.5/5

Related

Entertainment

Shia LaBeouf to undergo judge-ordered rehab after Mardi Gras incident

Actor Shia LaBeouf’s raucous Mardi Gras episode in New Orleans earlier this month has now earned him court-ordered drug and alcohol treatment.

A New Orleans judge on Thursday ordered the former Disney Channel star, 39, to begin substance abuse treatment and undergo weekly drug testing after he was arrested on suspicion of assaulting two men in the city’s famed French Quarter. He was charged with two counts of simple battery, the Associated Press reported.

“Transformers” and “Honey Boy” actor LaBeouf agreed to the updated terms of his release, including posting bond of $100,000, and underwent a drug test during his court appearance on Thursday. His attorney said the test did not show illegal substances in the actor’s system.

Orleans Parish Criminal Court judge Simone Levine criticized LaBeouf for his behavior during the Mardi Gras celebrations. In addition to striking the two men at a bar, LaBeouf allegedly yelled homophobic slurs. Levine expressed concern for “the safety of this larger community” and said LaBeouf “does not take his alcohol addiction seriously.”

A legal representative for LaBeouf did not immediately respond to a request for comment but said during the actor’s court appearance that “being drunk on Mardi Gras is not a crime.”

The actor has yet to enter a formal plea to the charges.

The New Orleans Police Department said its officers responded to a report of an assault in the 1400 block of Royal Street. The former “Even Stevens” child star was “causing a disturbance” at the business, leading staff to remove him from the premises, police said. The actor allegedly “used his closed fists” on one of the victims “several times.”

Authorities said LaBeouf left the business but returned, “acting even more aggressive.” According to the incident report, an unspecified number of people tried to subdue him and eventually let him go “in hope that he would leave.” Instead, police said, LaBeouf began assaulting the same man as before, hitting his upper body with closed fists. The actor is accused of punching the second man in the nose.

People held down LaBeouf until officials arrived. He was transported to a hospital and treated for unknown injuries and was arrested and charged upon his release.

An additional police report identified a local entertainer as one of LaBeouf’s alleged victims. The “Megalopolis” actor, whose history of violent behavior has led to previous arrests and other legal troubles, allegedly threatened the man’s life and shouted homophobic slurs.

Levine ordered that LaBeouf refrain from contacting the two victims and visiting the bar at the center of the brawl. She also denied his travel requests.

Hours after news of the brawl and his arrest spread, LaBeouf issued a brief statement on social media.

He posted to X: “Free me.”

Movie Reviews

‘Scream 7’ Review: Neve Campbell Returns for a Back-to-Basics Sequel That’s a Little Too Basic

The “Scream” movies, at their best, are delectable booby-trapped entertainments, and part of that is how cleverly they stay a step ahead of us. But there’s a moment in “Scream 7” that typifies the sensation this new movie gives you: that it’s leading the audience and lagging behind it at the same time.

We’re watching a homicidal pursuit through the home of Sidney Prescott (Neve Campbell), who is not only back but once again the central character (let’s call her the Final Girl as Mom). Sidney and her teenage daughter, Tatum (Isabel May), a kind of Final Girl in Training, are attempting to elude the blade of Ghostface. There’s a good bit where they inch along a catwalk behind the living-room wall, with Ghostface stabbing it from the other side. He misses, and they wind up on the street outside, where the killer gets smashed by a car that comes barreling out of nowhere (the driver, in fact, turns out to be an old friend).

The killer’s costume-shop Edvard Munch mask gets pulled off, revealing his identity, and this is followed by some chatter about how Ghostface often turns out to be more than one person. You don’t say! Considering that we’re only 45 minutes into the movie, that’s kind of a super duh. “Scream 7” is inadvertantly revealing its true theme, which is: Does anyone even care anymore who Ghostface is? Once all the obvious suspects have been eliminated, the answer is destined to be as arbitrary as it is forgettable.

The last two “Scream” films were nothing if not busy — nearly antic at times, stuffed to the bloody gills with backstory and mythology and schlock trivia. Yet there’s no denying that that was part of what kept the pulse of the series alive. In the lead-up to “Scream 7,” however, the busy quality seemed to transfer over to the drama offscreen: the firing of Melissa Barrera after comments she made that some judged to be antisemitic; the bowing out of Jenna Ortega; the fight over Neve Campbell’s salary (she sat out “Scream VI”); the fact that the directors who’d taken over the franchise, Matt Bettinelli-Olpin and Tyler Gillett, opted out, and their replacement, Christopher Landon, then quit after he started getting death threats over Barrera’s firing.

As if to calm the waters, the reins were handed back to Kevin Williamson, who 30 years ago wrote and created the original “Scream.” He was the series’ true auteur: the one who devised the whole concept of a meta slasher movie, a trash thriller maze that would be equal parts straight horror and a hack-’em-up version of Trivial Pursuit.

But Williamson returns to the “Scream” franchise, now directing one of the films for the first time, with a weirdly restricted agenda. The whole slaughter-movie scholarship side of the “Scream” films — “Look! We’re deconstructing the prospect of our own deaths like horror-film-class geeks!” — has basically been played out. And the series is all too aware of that. Williamson knows that he can’t just go back to that age-of-VHS ’90s drawing board. So what he’s done instead is to return the series to its “roots” in a straightforward, analog, Jamie Lee Curtis-in-the-rebooted-“Halloween”-franchise sort of way. “Scream 7” has enough shocks and yocks to keep the product churning and the audience, at least for a weekend, turning out. Williamson has gone back to basics, but the result is a “Scream” sequel that, while it nods in the direction of being seductively convoluted, is really just…basic.

The teenage Tatum, named for Sidney’s late lamented bestie (the Rose McGowan character from the original “Scream”), has a boyfriend, Ben (Sam Rechner) who smirks too much, along with a minor circle of friends who could all, theoretically, be suspects. But they get bumped off with a regularity that lets us know the mystery is elsewhere. One of the murders is a grisly piece of showmanship: Hannah (Mckenna Grace), flying around on a harness as she rehearses the high-school play, gets slashed with Ghostface’s knife until her innards fall out. But that scene is the exception to the film’s rule of routine “sensational” killings. Simply put, “Scream 7” isn’t very scary, and it isn’t very inventively gory (which some of the sequels have been).

The film opens with a fun variation on the ritual Ghostface phone call: Scott and Madison (Jimmy Tatro and Michelle Randolph) are visiting the former home of Stu Macher, which has been turned into a slasher museum. Among the nostalgic artifacts is a life-size Ghostface model that turns its head via movement sensors. Roger L. Jackson is once again the voice of Ghostface (the aggro psycho as AM radio DJ), and all of this erupts into a satisfyingly incendiary prelude.

But once “Scream 7” settles into its main story, Williamson adopts a tone of mordant sincerity regarding Sidney and the trauma she can’t seem to outrun. Courteney Cox’s Gale Weathers shows up, and she too becomes a major player, though the “media” commentary is strictly pro forma. The film has better luck reviving Matthew Lillard’s Stu, a character we were certain was dead‚ and he may in fact be. But then how is Stu, with mottled skin, calling up Sidney and conducting threatening live video-phone chats with her? Lillard’s raging performance could almost be his answer to Quentin Tarantino’s dis of him. The actor, like the character, is saying, “I’m still here,” and that’s true even if Stu is just a deepfake.

As Mindy, the aspiring TV news reporter who’s working for Gale, Jasmin Savoy Brown gets to deliver the film’s few token snippets of horror-snob geekery, and she’s so good at it that she made me wish Williamson had included more of it. Maybe the reason this stuff got so played out is that the series, creatively speaking, could actually use a more expansive vision of what horror movies are. But that’s not about to happen, because the “Scream” films are so successful they’re now effectively trapped in a genre that can’t risk being too smart about playing dumb.

-

World1 day ago

World1 day agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts2 days ago

Massachusetts2 days agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Montana1 week ago

Montana1 week ago2026 MHSA Montana Wrestling State Championship Brackets And Results – FloWrestling

-

Oklahoma1 week ago

Oklahoma1 week agoWildfires rage in Oklahoma as thousands urged to evacuate a small city

-

Louisiana4 days ago

Louisiana4 days agoWildfire near Gum Swamp Road in Livingston Parish now under control; more than 200 acres burned

-

Technology6 days ago

Technology6 days agoYouTube TV billing scam emails are hitting inboxes

-

Denver, CO2 days ago

Denver, CO2 days ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Technology6 days ago

Technology6 days agoStellantis is in a crisis of its own making