World

Migration: Naval blockades are an act of war so what’s left for Italy?

After a sudden influx of migrants overwhelmed the island of Lampedusa, Italy is rushing to come up with an effective method to curb new arrivals, with an open willingness to test the limits of international law.

The images of Lampedusa, an island of over 6,500 citizens crowded by more than 10,000 asylum seekers within days, have unleashed a new political crisis in Italy, which has long carried the unenviable responsibility of being the go-to destination for undocumented migrants wishing to reach the European Union.

Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, who last year formed the most hard-right government in Italian history, reacted by vowing to take “extraordinary measures” to drastically reduce the influx of migrants “managed by unscrupulous traffickers.”

Meloni made a direct appeal to Brussels framing the emergency situation in Lampedusa as a pivotal question that the whole of Europe must answer as one.

In a recorded speech, Meloni said Italy wants “a total paradigm shift: stop human traffickers and mass illegal immigration upstream, and focus on the defence of the external borders”.

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen quickly flew to Lampedusa with a 10-point action plan that mostly included old ideas but one succinct proposal caught the attention of politicians and journalists.

“Explore options to expand naval missions in the Mediterranean,” it reads.

The choice of words wasn’t coincidental. Meloni had demanded a “European mission, including a naval one if necessary” to prevent migrant vessels from ever reaching Italy. Her interior minister, Matteo Piantedosi, called for an even more radical solution: a naval blockade

‘No vessels in, no vessels out’

It didn’t take long for the term naval blockade (“blocco navale” in Italian) to make headlines across the EU and inflame the debate.

But although talks of blockade might be appealing for politicians who rely on an exasperated electorate to stay in office, the concept entails extremely serious consequences.

Strictly speaking, any blockade, be it by sea, air or land, is considered an act of war and requires the existence of at least two belligerents, one of whom conducts the operation in order to isolate the other from commercial flows, supply chains and communication lines. The ultimate goal is to cripple the adversary’s military and hamstring its economic growth.

Ongoing cases of blockades are Russia’s continued obstruction of Ukraine’s access to the Black Sea, the Saudi Arabia-led blockade imposed on Yemen, and Israel’s stringent restrictions along the Gaza Strip.

“A naval blockade is not a peacetime operation. A naval blockade only occurs, as it’s currently understood, during international armed conflict,” Phillip Drew, an assistant dean at Queen’s University and author of the book The Law of Maritime Blockade, told Euronews in an interview.

“Part of the requirement for a blockade is that it blocks everything. No vessels in, no vessels out. It doesn’t matter what their intent is. It doesn’t matter who owns them.”

As Italy and Tunisia are nowhere near an armed conflict – in fact, they are bound by a new memorandum of understanding – a naval blockade is out of the question, says Drew, who believes “the use of the terminology is unfortunate.”

Italy can still establish a conventional naval operation to deter migrant vessels from arriving at its shores. In order to achieve maximum efficiency, experts say, the intervention should be carried out as close as possible, or even inside, the Tunisian coastline to prevent vessels from even departing.

But such a 24-hour presence at sea would be extremely time-consuming and resource-intensive for a country, and would fall foul of international law, including a prohibition to operate in the territorial waters of another sovereign state, which extend to up to 12 nautical miles (22 kilometres) from its baseline.

There are, however, two ways to bypass this prohibition: securing the explicit consent of the sovereign state (in this case, Tunisia) or obtaining a resolution from the United Nations Security Council that legalises the military intervention.

Both scenarios, alluded to by Italian officials, face an uphill struggle.

In the memorandum of understanding, Tunis added a paragraph in which it “reiterates its position that it is not a country of settlement for irregular migrants” and “its position to control its own borders only”.

Obtaining help from the UN Security Council, where Russia holds veto power as a permanent member, might prove even harder. The Security Council would need to conclude that, based on Article 39 of the UN Charter, the influx of undocumented migrants departing from Tunisia constitutes a threat to international peace and security.

This qualification would enable countries to introduce all sorts of remedies to restore order in the region. Article 42 speaks of “demonstrations, blockade, and other operations by air, sea, or land forces” as possible methods.

“If the Security Council were to say: ‘All right, we’re going to require Tunisia to allow other forces in.’ That’s a significant imposition on the sovereignty of a nation of the United Nations. And that is not something that is done on a whim,” said Professor Drew.

“It would require a very serious circumstance. This is a serious circumstance, but it certainly isn’t a first option. It would be a last-ditch option.”

Sophia’s unexpected comeback

Faced with legal quandaries and logistics nightmares, Italy is looking at the past to find a future-proof solution.

The name of Sophia has been invoked as a blueprint for a maritime operation that could successfully prevent migrants from reaching Italy — without risking breaching international law.

Set up in May 2015, Sophia was an EU naval mission designed to combat networks of human smugglers and traffickers in the southern and central Mediterranean. It had an annual budget of almost €12 million and used military boats provided by member states to monitor the waters for suspicious activities.

The EU Council structured Sophia in three phases but only the first two stages were ever activated, allowing the mission to board, search, seize and divert vessels believed to be illegally transporting migrants.

Sophia’s exact geographical scope was confidential but the patrolling took place near Libya, a country engulfed by a chaotic civil war and exploited by smugglers as a getaway. The mission’s mandate was later reinforced by a UN Security Council resolution to enforce the arms embargo against Libya.

Although its main goal was to crack down on human trafficking, Sophia was firmly bound by two fundamental norms: the duty to rescue people in distress and the principle of non-refoulment, which forbids countries from sending asylum seekers to a country where they face a risk of torture, persecution or any other serious harm.

According to the EU Council, Sophia saved almost 45,000 people at sea.

Austria, Hungary and Italy claimed this demonstrates the mission was a “pull factor” that encouraged migrants to cross the Mediterranean in hopes of being saved by Sophia and taken to European soil.

The mission was terminated in March 2020.

Now Italy wants to finish the work. “The naval blockade could be included in the Meloni Agenda, as the prime minister explained, if the Sophia mission were to be completed,” Minister Piantedosi told Radio1, referring to the third phase.

Under Sophia’s third phase, naval forces would be empowered to take “all necessary measures” against vessels suspected of human smuggling or trafficking, “including through disposing of them or rendering them inoperable.” Crucially, this forceful intervention would take place inside the “territory” of a sovereign state.

For the European Commission this would not amount to a blockade, as Piantedosi suggested, as the destruction of vessels could only be carried out after assisting the migrants on board.

What’s more, it would be constrained by the same obligations that applied to the original mission: respect for national sovereignty, international consent and the duty to rescue.

“With respect to phase three of Sofia being a blueprint, I don’t see that happening anytime soon. Absent consent under international law, there is no way to move into the territorial waters of Tunisia to effectuate any dismantling, at least from a European Union perspective,” said Joyce De Coninck, a post-doctoral fellow with Ghent University who has researched Operation Sophia.

During Sophia’s existence, neither Libyan consent nor a UN resolution was ever obtained. The absence left EU boats patrolling a wide area of international waters, as originally envisioned, rather than working closer to the Libyan coastline.

“At best, an operation that replicates Sophia would be operation phase two of Sophia, which allowed for boarding, search, seizure and and diversion on high seas,” De Coninck told Euronews. “But again, that would entail that human rights obligations are triggered as soon as you are in physical proximity of a distressed vessel.”

World

Night Court Renewed for Season 3

ad

World

Colombia cuts diplomatic relations with Israel, but its military relies on Israeli technology

Colombia has become the latest Latin American country to announce that it will break diplomatic relations with Israel over its military campaign in Gaza, but the repercussions for the South American nation could be broader than for other countries because of longstanding bilateral agreements over security matters.

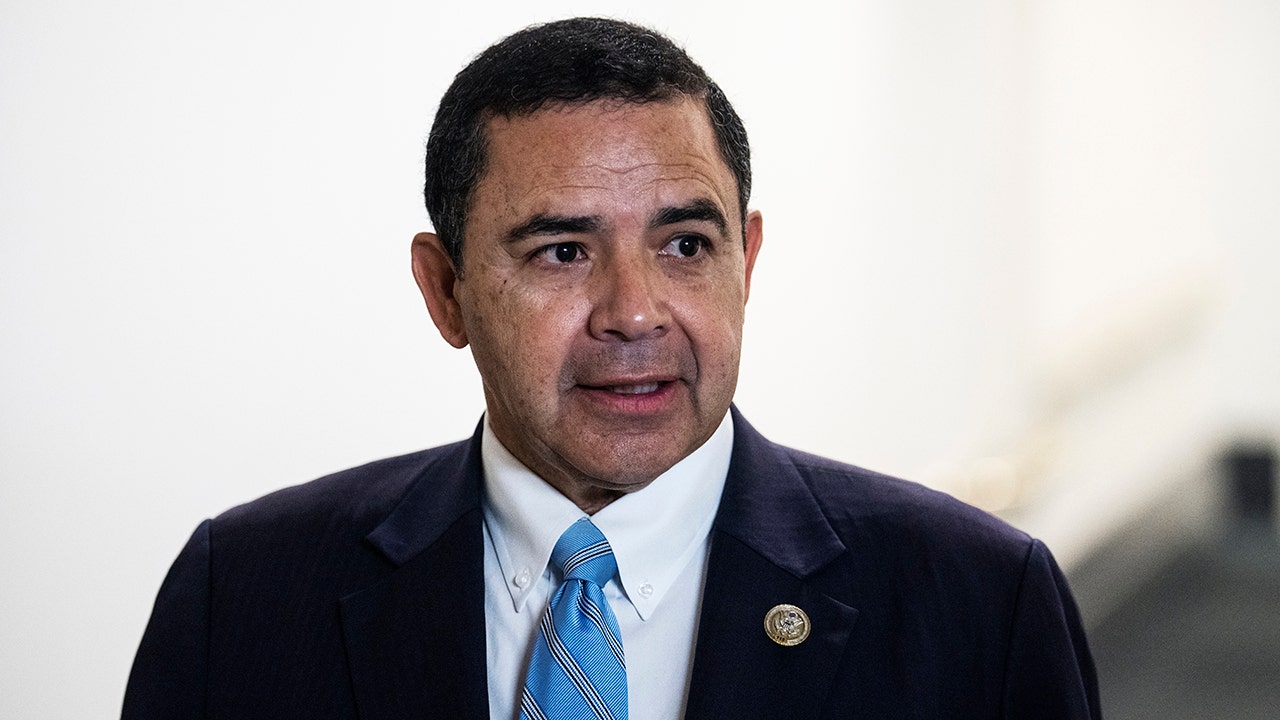

Colombian President Gustavo Petro on Wednesday described Israel’s actions in Gaza as “genocide,” and announced his government would end diplomatic relations with Israel effective Thursday. But he didn’t address how his decision could affect Colombia’s military, which uses Israeli-built warplanes and machine guns to fight drug cartels and rebel groups, and a free trade agreement between both countries that went into effect in 2020.

Also in the region, Bolivia and Belize have severed diplomatic relations with Israel over the Israel-Hamas war.

COLOMBIA’S PRESIDENT SAYS HUNDREDS OF THOUSANDS OF PIECES OF AMMUNITION HAVE GONE MISSING FROM MILITARY BASES

Here’s a look at Colombia’s close Israel ties and fallout:

WHY IS SECURITY COOPERATION BETWEEN COLOMBIA AND ISRAEL IMPORTANT?

Colombia and Israel have signed dozens of agreements on wide-ranging issues, including education and trade, since they established diplomatic relations in 1957. But nothing links them closer than military contracts.

Colombia’s fighter jets are all Israeli-built. The more than 20 Kfir Israeli-made fighter jets were used by its air force in numerous attacks on remote guerrilla camps that debilitated the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia. The attacks helped push the rebel group into peace talks that resulted in its disarmament in 2016.

Colombian President Gustavo Petro speaks at the International Workers’ Day march in Bogota, Colombia, on May 1, 2024. Petro on Wednesday announced his government would end diplomatic relations with Israel. (AP Photo/Fernando Vergara)

But the fleet, purchased in the late 1980s, is aging and requires maintenance, which can only be carried out by an Israeli firm. Manufacturers in France, Sweden and the United States have approached Colombia’s government with replacement options, but the spending priorities of Petro’s administration are elsewhere.

Colombia’s military also uses Galil rifles, which were designed in Israel and for which Colombia acquired the rights to manufacture and sell. Israel also assists the South American country with its cybersecurity needs.

WILL PETRO’S ANNOUNCEMENT AFFECT COLOMBIA’S MILITARY-RELATED CONTRACTS WITH ISRAEL?

It remains unclear.

Colombia’s Foreign Ministry said Thursday in a statement that “all communications related to this announcement will be made through established official channels and will not be public.” The ministry didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment from The Associated Press, while the Israeli Embassy in Bogota declined to address the issue.

However, a day before Petro announced his decision, Colombian Defense Minister Iván Velásquez told lawmakers that no new contracts will be signed with Israel, though existing ones will be fulfilled, including those for maintenance for the Kfir fighters and one for missile systems.

Velásquez said the government has established a “transition” committee that would seek to “diversify” suppliers to avoid depending on Israel. He added that one of the possibilities under consideration is the development of a rifle by the Colombian military industry to replace the Galil.

Security cooperation has been at the center of tensions between the two countries. Israel said in October that it would halt security exports to Colombia after Petro refused to condemn Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack on southern Israel that triggered the war and compared Israel’s actions in Gaza to those of Nazi Germany. In February, Petro announced the suspension of arms purchases from Israel.

For retired Gen. Guillermo León, former commander of the Colombian air force, the country’s military capabilities will be affected if Petro’s administration breaks its contract obligations or even if it complies with them but refuses to sign new ones.

“At the end of the year, maintenance and spare parts run out, and from then on, the fleet would rapidly enter a condition where we would no longer have the means to sustain it,” he told the AP. “This year, three aircraft were withdrawn from service due to compliance with their useful life cycle.”

WHAT IS THE TRADE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE TWO COUNTRIES?

A free trade agreement between Colombia and Israel went into effect in August 2020. Israel now buys 1% of Colombia’s total exports, which include coal, coffee and flowers.

According to Colombia’s Ministry of Commerce, exports to Israel last year totaled $499 million, which represents a drop of 53% from 2022.

Colombia’s imports from Israel include electrical equipment, plastics and fertilizers.

Neither government has explained whether the diplomatic feud will affect the trade agreement.

World

Meloni plans to rally Europe's centre-right in elections pledge

In the run-up to the European elections in June, Euronews takes a closer look at the Brothers of Italy party leader and the country’s prime minister’s speech in Pescara.

The Brothers of Italy’s conference in Pescara was more than a party gathering to launch Meloni’s electoral campaign.

The event marks a key moment in the run-up to the European elections in June, with the Italian prime minister’s address last Sunday providing crucial insight into her conservative leadership in Europe and her EU goals.

At the event, she announced that voters should use just her first name on their ballots. “Call me Giorgia,” she said.

The move is legal, and while many, including her rivals, have criticised her decision, it aligns with her image as a leader with working-class roots who took her first step into politics in Rome’s Garbatella district.

In both her role as Italy’s PM and president of the ECR group, Meloni outlined her vision for Europe.

Notably, she spoke of Brothers of Italy’s increased support over the years since the last European elections in 2019, while commenting on her ambitions to extend what her party has achieved in Italy to the rest of Europe.

“We want to do in Europe what we did in Italy … create a majority that brings together the centre-right forces and send the left into opposition,” Meloni said in Pescara in what has since been highlighted as a key statement.

Alliances based on issues, not ideals

A closer look at Meloni’s speech can help better understand what she has in mind. As ECR Co-Chairman Nicola Procaccini told Euronews, “Meloni refers to a spectrum of positions which sees both the ECR and the EPP as the two main axes when she talks about the creation of a majority that brings together centre-right forces.”

“Then, some delegations from ID in the right-wing camp,” adds Procaccini, “along with others from Renew Europe … will make up the total number that is needed to reach the majority to vote in favour of some measures.”

According to Procaccini, it is crucial to understand that the idea of “majority” within the new 720 seats-strong European Parliament is not fixed and that finding common ground with other political forces remains a possibility.

“Majorities or minorities form themselves based on the single vote. I do believe that the balance within the next European Parliament will shift to the right,” Procaccini said, adding that the EPP and a large part of Renew Europe are already voting alongside ECR, PiS or Viktor Orban’s Fidesz.

“It’s already happening today,” Procaccini continued, “not because there’s a deal in place, but based on the issues we are voting on.”

And as for sending the left into opposition, “it’s about giving the EPP the possibility to break the bond it has built with the socialists and the greens,” Brothers of Italy MP Sara Kelany told Euronews.

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoLarry Webb’s deathbed confession solves 2000 cold case murder of Susan and Natasha Carter, 10, whose remains were found hours after he died

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoHaiti Prime Minister Ariel Henry resigns, transitional council takes power

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoFirst cargo ship passes through new channel since Baltimore bridge collapse

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoUS secretly sent long-range ATACMS weapons to Ukraine

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoSpanish PM Pedro Sanchez suspends public duties to 'reflect'

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoAmerican Airlines passenger alleges discrimination over use of first-class restroom

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoHumane (2024) – Movie Review

-

Education1 week ago

Education1 week agoVideo: Johnson Condemns Pro-Palestinian Protests at Columbia University