Sports

Daniel Jones gets scrappy as Giants, Lions get into multiple altercations during joint practice

Two NFL teams practicing in 90-degree heat in August — what could go wrong?

Well, the New York Giants and Detroit Lions got into at least a couple of big altercations at their joint training camp practice at Big Blue’s facility on Monday.

The Lions made the trip to New Jersey for two days worth of practice, and it didn’t take much time for tempers to boil over.

Daniel Jones #8 of the New York Giants throws the ball during New York Giants OTA Offseason Workouts at NY Giants Quest Diagnostics Training Center on June 6, 2024 in East Rutherford, New Jersey. (Luke Hales/Getty Images)

Perhaps the biggest fight started after Amon-Ra St. Brown and Dru Phillips exchanged pleasantries, with the All-Pro receiver shoving the Giant before both sides came together, and several other players exchanged blows.

But the big surprise came a little later on, when Giants quarterback Daniel Jones was one of the first to get down and dirty in another melee.

Giants offensive lineman Jon Runyan was pinned on the ground by a Lions defensive lineman, which irked the quarterback, and he delivered a hit from behind.

“Situation happens like that, try to stand up for your guys,” Jones said afterward.

(L-R) Daniel Jones #8 and head coach Brian Daboll of the New York Giants during New York Giants OTA Offseason Workouts at NY Giants Quest Diagnostics Training Center on June 06, 2024 in East Rutherford, New Jersey. (Luke Hales/Getty Images)

SIMONE BILES’ NFL HUSBAND JONATHAN OWENS SAYS HIS WIFE IS ‘THE S—‘

Jones is coming off a torn ACL he suffered on Nov. 5 against the Las Vegas Raiders, but he has been a full-go in training camp — clearly.

It was a disappointing season for Big Blue, as they went 6-11 after surprisingly making the playoffs in 2022. However, as shown in Hard Knocks, they are much improved on paper after acquiring Brian Burns, new offensive linemen, and drafting Malik Nabers with the sixth pick.

The Lions, meanwhile, were just a half away from their first ever Super Bowl appearance, but they choked away their 24-7 halftime lead that sent the San Francisco 49ers back to the big dance.

Daniel Jones #8 of the New York Giants takes the field before a game against the Las Vegas Raiders at Allegiant Stadium on Nov. 5, 2023 in Las Vegas, Nevada. (Ian Maule/Getty Images)

The two will open up the preseason against one another on Thursday night at MetLife Stadium.

Follow Fox News Digital’s sports coverage on X, and subscribe to the Fox News Sports Huddle newsletter.

Sports

Access all areas for a Premier League club's pre-season tour in the U.S.

In the scorching heat of Inter Miami’s training base in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, the final moments of Wolverhampton Wanderers’ morning training session are playing out.

“We are 1-0 up at the Emirates, two minutes to go, keep going,” urges the Wolves head coach Gary O’Neil. Wolves begin their Premier League season away at Arsenal’s Emirates Stadium on August 17 and, even here, some three weeks before the match, O’Neil is focusing minds.

The final drill is an energy-sapping exercise in which O’Neil divides his group into four teams of four outfield players, with two goalkeepers remaining in their goals for the entire session. Each team of four have three-minute cycles, in which they compete in a 30-by-20-metre area. One team, therefore, stays on for the entire three minutes and the other three teams come on fresh for a minute each. O’Neil calls it his “mentality” test.

“It is when you’re up against it, trying to behave as a team,” he explains. “You learn about individuals and how they respond under different stresses. We also want to include our principles, trying to protect the middle, trying to find a spare man and trying to build up. That is the aim, no matter what we do.

“This drill, it shows up your personal traits, it always gets you. You see exactly what people are.”

Toti Gomes, the Wolves defender, is a standout. “If you’re doing that drill, you want Toti in your team. He doesn’t suffer badly from disappointment. If a goal goes against his team, he picks himself up. When he gets tired, he’s not bothered. He knows he’s there to work. In this drill, you can be 5-0 down because another team keeps coming on fresh. He’s stable emotionally.

“We have got some emotional ones in the group that struggle with conceding a goal and getting ready to go again. So it’s a good drill for us.”

The winning team of that 4×4 drill, Chiquinho, Jorgen Strand Larsen, Hugo Bueno and Pablo Sarabia (Jack Thomas – WWFC/Wolves via Getty Images)

As for the Emirates reference? “It’s to show them that we’re not doing this for now. It’s for when we get somewhere and it matters, so we hang in and we survive. I am trying to give them little pictures on why we do stuff and why it’s important not to drop your level for the last minute. It’s for when we really need it.”

This is just one insight during a three-day period in which the Premier League side opened their doors to The Athletic and provided unrestricted access to their first visit to the United States in 43 years.

Before fixtures against Premier League rivals West Ham United and Crystal Palace, as well as German side RB Leipzig, Wolves based themselves at the Florida Blue training centre, preparing for the season just a couple of pitches down from the MLS team part-owned by David Beckham and starring Lionel Messi. O’Neil impressed during his first season in charge, leading Wolves to doubles over Tottenham Hotspur and Chelsea, while also beating Pep Guardiola’s Manchester City. Saturday evening’s 3-0 win over Leipzig was capped by a glorious team goal, which swiftly had social media salivating on Sunday morning.

The best goal you will see today 😍 pic.twitter.com/3K0BjXLREQ

— Wolves (@Wolves) August 4, 2024

During our time together, no area was out of bounds. The Athletic watched training sessions, spoke to O’Neil, the team’s players, the team’s performance and sport science specialists, the club kitman, the head chef, the nutritionist, as well as the head of operations responsible for bringing the entire visit together.

Along the way, we joined the Wolves players on a river taxi across Fort Lauderdale and then flew with the team on a chartered flight to Jacksonville — a flight delayed to make way for Israel Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s exit from Florida. The result, hopefully, is a report that tells you everything you may have ever quietly wondered about what really goes on during pre-season.

Two weeks to ‘deload’ and heart-rate monitors at home: What happens between the end of the season and pre-season?

Matt Doherty, the Wolves full-back, is on the top deck of a boat traversing Fort Lauderdale when he reflects on some of his more brutal pre-season experiences. He is now in his second spell at the club, having spent a decade at Wolves and then periods with Tottenham and Atletico Madrid, before returning to Wolves in 2023. He recalls his earlier summers at Wolves under Kenny Jackett, when the team were in League One in 2013. He laughs: “We were doing 7am runs before we even had breakfast. And I was overweight at the time. So I didn’t enjoy that.

“Times are changing — it’s not just old-school running now where you just absolutely blast it all the time. People’s bodies can’t take it now. Some people train for five days in a row, and then all of a sudden they need a day or two off. That’s not how it used to be.”

Wolves full-back Matt Doherty (Jack Thomas – WWFC/Wolves via Getty Images)

More traditional approaches do remain, as Doherty discovered while on pre-season under Antonio Conte at Tottenham. “We were throwing up out of both ends by the time we had finished. That was the hardest pre-season I did. Ever. That was crazy. But we hung off every word that he said and rightly so. I can’t speak highly enough of him.”

The big change, Doherty says, is the way players now look after themselves between the end of a previous campaign and the start of pre-season. “I used to be a disaster every summer. I didn’t know what I was doing. I’d still exercise but I’m an eater. I was just eating houses down wherever I went. You have to maintain yourself or you will be left behind. People may say, ‘Isn’t this what pre-season is for? To get fit?’. To a point, yes, but you can’t come back in disgrace, as I have done in the past.”

At the end of last season, Wolves gave their players a two-week window to “deload”, according to Phil Hayward, the club’s head of high performance. “A fortnight where they don’t have to worry about doing anything at all.

“The mentality of the players is very different to when I started in 2008. It was a real battle to get guys to do anything in the off-season, they came back a stone overweight, they had been away on lads’ holidays. You’d spend the first bit of pre-season trying to get weight off them and back somewhere near to where they needed to be for the season.

“Now it’s gone the opposite way. It is partly driven by social media. Now the battle tends to be trying to make sure they get rest and don’t do too much. A lot of guys want to do extra stuff in their own time. Some have people they work with in their own countries, which brings challenges in terms of communication and lots of other issues around liability insurance. If we are letting them see somebody, how do we coordinate that? That’s become a big part of my job in the last few years, liaising with people in the players’ circle.”

When Wolves players go away for the summer, some have a clear period to relax, while others go to the European Championship and Copa America. The players are given GPS devices and heart rate monitoring belts to take home, and Hayward says it enables the club to keep an eye on a player’s “internal loads” as they ease themselves back into shape before pre-season.

Joao Gomes in action for Brazil at the Copa America (Maciek Gudrymowicz/ISI Photos/Getty Images)

“It means we get real-time information about what they’re actually doing and make sure they’re following a plan,” he says. “We want them to get back to individualised baselines. The off-season training program is to make sure they come back in a decent state, to be able to then drop into our main programme with the squad.”

How much damage can a player really do in that period before pre-season? “From an aerobic perspective, you’ll start to decondition after a couple of weeks. Even if a player is out for a week with a minor injury, there is a drop-off from a cardiovascular fitness perspective, physiologically. It’s almost impossible to say exactly how much fitness they have lost between seasons. But once they get back into the training programme, we look at heart rate data and their physical output. It is to see how they’re responding to a given session compared to how they responded to a very similar session before the end of last season. There is definitely a percentage drop-off.”

First-day nerves, blood tests and daily questionnaires: The start of pre-season

Day one back at the training ground is testing day. Doherty says it is a day he cannot wait to be over. “There are nerves. It is not like, ‘Oh my God’, but you just want to know the results and hopefully be in the middle, the same as everybody else and kind of hide away’.”

Hayward explains that testing involves medical assessments with the club doctor, blood tests and ultrasound scans. For outfield players, there is an emphasis on testing the main tendons, especially in the lower limbs, while for goalkeepers, shoulder assessments are key.

He says: “If they have an issue in the season, we then refer back to those images and compare it back to when we know everything was fine. The blood tests are looking for micronutrients. We work closely with the nutritionist to decide which particular panel of blood tests we want to do. That is individualised to different players as well, according to what we know of their history, biochemistry, and their normal deficits. It helps us know if someone’s always low on vitamin D, for example, and if we can support that with supplements.

“We are also looking for general health markers. That’s how we first found out about Carl Ikeme’s problem a few years ago (the former Wolves goalkeeper was diagnosed with leukaemia after posting abnormal pre-season blood test results). We have a general medical consultation with them: how have they been over the summer, any new issues, any illnesses you’ve not told us about? Mental health comes into that as well. Has anything gone on at home?”

One striking aspect is the extent of joined-up thinking between the club’s sports science practitioners and the coaching staff. This is O’Neil’s first full pre-season as a head coach — he took over Wolves five days before the start of the Premier League last season and had been named Bournemouth manager after the season started in the previous campaign. Wolves’ head of physical performance, Mark Piros-Read, has led multiple pre-seasons at Swedish side Malmo.

Hayward says: “Gary is a very collaborative boss. There are conversations between the coaching staff and Mark about what Gary wants to get from the sessions and what Mark needs to get from a physical perspective, so we try to find ways to get that physical conditioning into the players with the football. They gel really well in terms of planning the sessions to make sure that they both get what they require. It is more heavily focused physically at the early part of pre-season, with Mark having more input and then towards the start of the season, it becomes much more focused on football and culture.”

Phil Hayward, head of high performance, and Mark Piros-Read, head of physical performance (Jack Thomas – WWFC/Wolves via Getty Images)

Within sessions, O’Neil takes guidance from the sport science team. The players fill in daily questionnaires on their mobile phones, answering subjective queries about how they are feeling, how they slept, whether they have any fresh soreness or fatigue and how they feel in their stomachs. Some players wear Oura Rings, or Apple Watches, and proactively report their length and quality of sleep. The club do not insist on this, however, taking the view that it may be deemed invasive. Hayward says: “It’s difficult because you get paid a lot of money to be an athlete so that’s part of what you sign up to. But it maybe undermines the amount of trust you have from the players as well, if you insist.”

Any issue a player raises will be tested objectively and analysed by the medical and physio team.

Hayward says: “Gary is very receptive to that information. We’ve got players today who won’t do the whole session. They’ll be managed through the last part of the session because we compare this current week with their last four weeks. If there’s a huge spike, there’s a big increase in injury risk. That’s based on a lot of research. We call that acute chronic workload ratio.”

Wolves spent the first part of their pre-season in the Spanish resort of Marbella. The main event, however, will be in the United States.

Three types of pillow, WhatsApp location pins on nights out and Uno Flip: How does a club organise pre-season in the U.S.?

When Wolves’ commercial department secured the club’s participation in the Stateside Cup during the Spring, Matt Wild, the club’s general manager of football operations, sprang into action. Wolves’ overall touring party, including players, football staff, operations, commercial and media, stretched to 85 people over a 12-day visit that encompassed a game against West Ham in Jacksonville, Crystal Palace in Annapolis and Leipzig in Fort Lauderdale. For the logistics, the club handle, well, everything.

“The players just need to bring themselves and a wash bag,” jokes Sam Perrin, the head of kit at Wolves. “And sometimes they don’t even want to bring the wash bag.”

In the club’s view, this is not mollycoddling, but simply doing everything possible to ensure a player can perform at their best at the highest level. For travel to the U.S., visas are a necessity and the club take care of the administration.

Most of the club’s South American players already had U.S. travel visas, but 18-year-old Pedro Lima, signed on July 1, did not, so he was dispatched to the American embassy in London to turn around a fast-track application. The club needed to keep within budget for the tour — Wild estimates the cost to be £1,050,000 ($1,344,000) in total. The club flew on scheduled commercial flights from London to Miami, rather than private transatlantic chartered planes, which represented a significant saving. “We’re getting participation fees for being here, but we need to make sure the profit and loss works out.”

They flew in two groups because each group required a certain number of business, premium and economy flights, with the players in business class. When the club flew chartered from Fort Lauderdale’s private terminal to Jacksonville, the bus drove the travelling party directly from the hotel to the plane, avoiding the masses within the airport. An unexpected delay, however, came when Prime Minister Netanyahu, fresh from a visit to see Donald Trump in Mar-a-Lago, was travelling out of the same terminal, meaning an hour’s delay on the tarmac as Israel’s equivalent of Air Force One, and all the security detail this encompasses, was given priority.

A big decision was where to base Wolves during the tour. They considered an IMG training base in Tampa and another location by Ponte Vedra Beach in Jacksonville. Yet when an exhibition game against Leipzig at Inter Miami’s Chase Stadium came up — making Wolves the first English team to play at the stadium — they decided to locate themselves at Inter Miami’s training complex. “We knew the players would like it,” Wild says. “You have the beach nearby and it is where Lionel Messi trains.”

Wolves based themselves at Inter Miami’s Florida Blue training centre (Jack Thomas – WWFC/Wolves via Getty Images)

Wolves stayed in the W hotel in Fort Lauderdale. The hotel needed to fit specific requirements. Wild says: “We wanted exclusivity on several floors for our players, so they’re not sharing. But then you need to make sure that you’ve got good-sized rooms on each floor. We always make sure that we’ve got a good pillow. We’ve got three different types of pillows; some are hard, some are soft.

“We needed a good function space, a physio room, a dining room, a meeting room, a kit room. I needed somewhere for the coaching staff to work. We agreed that Inter Miami would do our laundry for us and they helped us source all our sports drinks and water.”

Meeting some famous faces at @InterMiamiCF 🙌 pic.twitter.com/dKcYvCU6uh

— Wolves (@Wolves) August 2, 2024

As Wild explains the intricate detail that goes into the tour, it can feel a little bit as though footballers are on a school trip. A WhatsApp group is made, where they are sent the schedule every night for the day ahead. It is explained to them what to say to airport security when they are entering the U.S.

Recreational activities are planned, such as the river taxi on the day The Athletic joins the team, and a visit to the Everglades several days later. Players are not provided with a per diem allocation which can be expensed, given that their travel and food are already included. Zlatan Ibrahimovic famously once complained that Manchester United had deducted the price of a fruit juice from a hotel minibar from his payslip.

The river taxi in Fort Lauderdale (Jack Thomas – WWFC/Wolves via Getty Images)

The club brings four members of its security team to the U.S., including Steve Sutton, the club’s director of safety and security. On the day we are talking, the players are afforded a night out, heading down to Miami. O’Neil tries to balance hard preparation — Doherty says the players have “worked their socks off” — and some escape. They are given a curfew of 11pm.

Wild says: “If our players go out, they have to pin their location so that we know where they are. It’s more for their safety. Our security team are really good at making sure everyone is accounted for. It’s just subtly staying in control.”

Every player meets the curfew. During the trip, the dynamics of the group are revealing. At the end of O’Neil’s mentality test, he asks every player to shake hands with one another, recognising that tensions can heighten during training, but reminds his players they are all on the same team. There are times the group can break into natural cliques; the British and Irish contingent sit together on the boat trip, as do the Spanish-speaking group. But it is also encouraging to see Wolves captain Mario Lemina in deep conversation with Luke Cundle, a returning loanee, while later on after dinner, 16-year-old Luke Rawlings, who only got his first pay packet the previous month, is receiving advice from the club’s £44million record signing Matheus Cunha.

(Jack Thomas – WWFC/Wolves via Getty Images)

Wild had planned ahead by organising a games room, ordering in a giant Connect 4, a Pac-Man console, a Marvel arcade game and a Cornhole set. As it transpires, the player’s game of choice during the tour appears to be the even more modest Uno Flip.

The planning is not only operational. Performance expert Hayward says his team prepared the players to be ready to work in a new time zone, five hours behind the UK.

“We flew over on Tuesday. But we had a double session on Monday in England. We have these light glasses,” he explains. “What we’re trying to do there is create a stimulus from a light perspective, to give the perception of it being similar to the midday sun. So we got them to wear the light glasses on Monday evening after training, to almost try and trick the brain and ready them for a new time zone.

“When we arrived in the U.S., we made sure the guys all stayed up until 10.30pm and then advised them to stay in bed until at least 7am the next morning. The doctor also provided melatonin tablets for them in the evening to help them with getting to sleep more quickly and have a deeper sleep, therefore avoiding what normally happens when you travel west and wake up in the middle of the night.”

As for the searing heat and sweat-inducing humidity? He says: “Some argue it doesn’t make sense to be here because it’s so different from the climate back in the UK. You are used to training in 30 per cent humidity and 20C (68F) heat and that’s where your matches are going to be played. So why would you come to 90 per cent humidity and 35C? But there are a lot of physical and physiological benefits from training in heat, similar to the effect you get from altitude training. Heat creates a greater physical challenge for the players.

“You can get more bang for the buck from an internal load perspective without having the same external load in actual physical load through the joints. We want that overload. That’s intentional. We don’t want to spend a lot of time working on ways to cool them down, because you want to challenge them more physiologically to try and get that response.”

(Jack Thomas – WWFC/Wolves via Getty Images)

Every precaution is taken, however, and Hayward’s previous life at the Los Angeles Galaxy gives him personal experience.

“There’s a quite extensive protocol about heat exhaustion and heat stress, and monitoring for that and how to respond if that happens. If we see symptoms of heat stress, we’ll follow protocol to cool them down in pretty large ice baths. We’ll measure the temperature to make sure they’re never at risk. We’ve got real-time heart rate. If someone’s heart rate is staying very high and they’re not recovering as well from a phase of the session as we’d expect them, that would probably be the first flag we’d see. We’ve got it on a tablet at the side of the pitch.

“We can also see from observing, if someone starts to behave slightly differently. When there’s a change in the drill, the doctor will get around the players and have a chat to make sure everyone’s OK.”

Two tonnes of kit, five types of boots – and being in charge of underwear: How do clubs clothe their players on tour?

For Perrin, the head of kit, this is his first transatlantic pre-season tour in his fifth season at the club. He says he liaised with his Chelsea counterpart while planning the tour, to hear things that work and don’t work.

If you constantly panic about having your phone, wallet and keys in your pocket, then the level of detail and pressure for Perrin sounds pretty overwhelming. “My wife calls it glorified babysitting,” Perrin jokes, but making sure the players are equipped is essential. Preparations are made weeks in advance. Wolves cargoed out two tonnes of kit and equipment ahead of arriving, as well as taking ten bags on each flight.

“One thing my old boss told me is, ‘Don’t give them an excuse to blame you’,” Perrin says. “Don’t let them be able to say, ‘The kit team didn’t do this, so that’s why I didn’t score’. You also want trust from the management team and respect from the players. If the players respect you, they don’t chuck stuff on the floor and expect you to pick it up.

“There’s so many different things that happen that you don’t think about as fans. An example: the electric voltage is completely different here. We had our heat press (to print numbers on shirts) shipped out just for any last-minute changes. Then the day we were travelling, the squad changed. So we set the printer up but it didn’t work because of the voltage. So I’m now panicking, how the hell am I going to print these shirts? In the end, we managed to borrow one from Inter Miami. It was almost a nightmare for me.”

More on the world of football boots and kits…

The club are responsible for organising every piece of sporting equipment that a player may require, down to the underwear that a player chooses to wear in training or during a game. In case you are wondering, most footballers wear Sloggi Y-fronts, a Swiss brand. “Black for staff, navy for players,” Perrin adds. “We supply them, wash them, refold them and put them back into kit rolls.”

A few players — Tommy Doyle, Pedro Lima, Rodrigo Gomes and Pedro Neto — however, choose a different brand, so they provide six pairs to the club, meaning the club will always have two available for the player for a matchday and up to four at the training ground.

Neto is one of those who provides his own underwear (Jack Thomas – WWFC/Wolves via Getty Images)

In a Premier League game, it is a requirement for every player’s shorts to be numbered. Yet for pre-season friendlies, this is not the case, so the club transport over a set number of non-numbered shorts. For the three games in the U.S., Perrin has brought over six matchday shirts for each player, as most Wolves players change into a fresh jersey at half-time. Craig Dawson, he notes, is the only one who will keep the same shirt for the second half. “He’ll take his socks off or down and he’ll redo his pads every time and resets himself in that way.”

The club also bring the player’s boots. In most cases, it is three each, meaning the players are equipped whether they need metal studs or moulds, and have a spare pair. “We’ve ended up bringing four boot bags. Unless you’re Matt Doherty, he’s bought five. Matt is one of the greatest kids. He has to feel right. If he fancies that pair of boots today, he’ll want to wear that boot. I’d rather just bring all five and then he can choose.”

Boots are cleaned by staff, a job made easier by superior modern pitches, usually requiring only a quick brush or rinse. “And then we dry them with a towel and hang them back up in the boot room, which is heated. We have two boot steamers and a boot oven outside. The oven softens the boots but keeps them dry. A steamer softens the boot a little bit more but wet. So in the winter months, you tend to use the oven more than the steamer because by the time you get outside, your feet are freezing cold.”

One hundred eggs at breakfast, 5am starts in the kitchen and performance-orientated dessert: How do clubs feed their players on tour?

As players exhaust their reserves during pre-season, refuelling becomes an essential component.

Wolves’ head chef, Melissa Forde, travels with the team for the trip, in addition to multiple members of her team. She works closely with Matt North, the club’s nutritionist, to devise menus catering for every scenario a player will face in pre-season. Forde speaks with The Athletic in Jacksonville, where she flew out before the team for the West Ham fixture, to make sure the evening meal service was in hand. It meant a 4.30am wake-up in Fort Lauderdale and by the time dinner is wrapped up, it is now 9.30pm. “I nearly fell asleep in my dinner last night,” she says.

Forde’s work is a passion project. Her background is as an executive chef at Birmingham’s Hippodrome theatre, having previously worked as a sous-chef at Marriott hotels. As far as she knows, she is the only female head chef at a Premier League club. She points to transferable skills from her previous roles; kitchen management, multitasking, catering en-masse for high volume or in banquet style, and also being able to walk into a hotel several times a month and understand the kitchen layout and operations. She sent the hotels her menu plans before the team flew out to the U.S., ensuring they sourced local produce for the team.

She then manages a team of her own staff and hotel staff to produce a spread befitting a Premier League club. For breakfast, her team will be up at 5am to prepare for the day, using more than 100 eggs at breakfast alone. There is no shortage of choice. When The Athletic joins Wolves for lunch, there is a vast salad bar, steamed and roasted vegetables, a vegetarian chickpea curry, barbecued chicken and a live cooking station preparing fajitas. Dessert offerings are Greek yoghurt and honey, or a fruit selection.

Melissa Forde, Wolves’ head chef (Jack Thomas – WWFC/Wolves via Getty Images)

She says: “I have a lot of freedom. If a chef’s creativity is silenced, it’s almost like you kill the chef within them.” At the training ground back in England, her “jerk chicken Wednesdays” have become a firm favourite, as have her themed days to mark moments in the calendar such as Black History Month. She has won over the Wolves playing squad by creating dishes familiar to their Portuguese background. In the case of Yerson Mosquera, the Colombian defender, he experienced homesickness when he moved to the club and she went out of her way to find ingredients from his own country to lift his spirits.

The menu itself is prepared in close collaboration with North, as well as the team’s sport science department who know what every training session will include, and the type of refuelling that will be required. North is in the dining room, subtly advising players on the type of food they need to take in. It takes time to develop trust after a player signs. Players are weighed daily, while their body fat is also measured using callipers at eight skin-folds on a monthly or fortnightly basis, depending on the player.

He says: “Nutrition can be quite judgmental. So if you’re coming into that environment and the first thing I’m doing is sitting down analysing your diet — then if you’ve got a predisposition to a negative behaviour towards food or not understanding them — it might not come across well. When they first sign, it is just about building relationships, small interactions, trying to give them tips rather than saying you’re doing something wrong.

“From a nutritional standpoint, when they sign for the club, they’ll get their bloods taken. Off the back of that, we’ll analyse what they need to increase or change within the diet, whether that’s supplements or actual food. The key ones are, calcium, vitamins B, C, D and K, and iron.”

Summer signing Pedro Lima (Jack Thomas – WWFC/Wolves via Getty Images)

The extent to which the body absorbs micronutrients differs from person to person, so sometimes two people could eat the same thing but absorb it differently. That is part of the reason supplements provide a crucial function.

One challenge can be to get players to eat enough food. North explains: “On an average training day, they’ll be burning upwards of 3,000 calories. On a heavy training day, they might do more much more, so we need them to have a big carbohydrate intake.

“The day before the game is when we’re trying to load the stores. So we’ll change the menu design to have more carbohydrates on board and the protein portions will be lower and the menu will be really low fat. The chefs have really clever strategies where they integrate more carbohydrates into dishes. We’ll use juices. We look at the satiation of foods. Potatoes are really satiating. So you can’t eat a lot of it. When they need to eat a lot more, we’ll put mashed potatoes on, which doesn’t fill you up as much, but we’ll push them more towards rice and pastas, which our players digest easier.

“You may think a diet for a footballer might be relatively clean with no sauces and condiments — but on a day before a game when we need more carbohydrates, we’ll have sweet and sour chicken — obviously adapted but the sauce will have a lot of carbohydrate, with the players not really knowing it. There’ll be a snack bar. The players are really big on pancakes, easily digestible and they can put toppings on, it really ramps it up. We have performance-orientated dessert. On a day we need a lot of carbs, that might be a rice pudding or a modified apple crumble. On the day when we need more protein, the chefs use high-protein yoghurts or whey protein.”

Unlike some other clubs, no foods are banned. Ketchup, often prohibited on the orders of head coaches, is available, because the nutritionist takes the view that if a small amount of sugar helps a player consume the large amount of protein — from an omelette, for example — it is worth it.

The players rarely need to be told off these days. Hayward says: “If we suddenly put out loads of burgers and pizzas at lunchtime, they’d be moaning about that. ‘Why are we being given this? It’s not right for us’.”

Pre-season matches and how do they help the season ahead?

O’Neil has been using his time in pre-season to attempt to adapt his team tactically. That is not easy when some players, such as Jose Sa, Joao Gomes, Nelson Semedo and Neto, only joined up with the team towards the back end of the tour following their exertions with Portugal at Euro 2024, while new players may yet arrive who will need to adapt to a new club.

O’Neil says he wants his team to be more aggressive without the ball this season and would also like to have the option of playing more regularly with four defenders rather than five. He says: “Having five defenders on the pitch does limit what you can do going forwards,” he says, before adding, “It’d be silly not to use this pre-season to try and nail the bits that we need to be a bit more aggressive.”

O’Neil’s first season at Wolves brought largely rave reviews but form did suffer between March and the end of the season, as Wolves exited the FA Cup against Coventry City and won only two of their final 12 Premier League games. They finished the season in 14th place, albeit only three points short of a top-half placing.

Wolves head coach Gary O’Neil (Jack Thomas – WWFC/Wolves via Getty Images)

Piros-Read, the team’s head of physical performance, is asked if there were things his team have learned as a result of that late-season drop-off. “If you look at a lot of our starting players, it was the biggest season they’ve ever had for the number of matches played,” he says. “Rayan Ait-Nouri, the year before didn’t play much at all. Lemina has only played one season similar to that before. Arsenal have players the bulk of whom have done 40 games each for the last few years. Even Max Kilman (who has since joined West Ham) had only done a year of that.

“But now we’ve got this base of a team who built that foundation last year, and will have that robustness. Jorgen Strand Larsen, our new signing up front, played a full season in La Liga, which will help us. This is probably something you don’t think about until you really look into it. If a player has only ever started 24 games, and he’s played 37. It doesn’t sound a lot to Joe Bloggs, but that is a lot bigger demand for a footballer over a season.”

The 3-1 victory against West Ham revealed that not even the most precise planning can account for every factor; first a prime minister held things up, then the match itself was delayed for two hours, amid torrential storms in Florida. The game was eventually played, the pitch holding out, and O’Neil joked he had learned more about weather in the previous hours than he ever thought possible.

The final game, a 3-0 demolition of German club Leipzig, was played amid wild rain storms. Every mobile phone in the area received a tornado warning shortly after the match. The game brought more optimism from a new signing, Rodrigo Gomes, a 21-year-old brought in from Portuguese team Braga this summer. He has scored three goals on the tour, with the pick of them rounding off a flowing team move against Leipzig.

As for the games themselves, do they really provide that pit-in-the-stomach feeling that a competitive game triggers? O’Neil says he feels more relaxed, more like a training day than a matchday.

“You can never really tell in training,” O’Neil says. “So getting into matchdays, seeing how they look, what sort of numbers they register, looking at team shape, issues within it, things we’ve worked on that they haven’t fully grasped or that they have grasped. It’s like an exam paper. You practise all week — and then there’s an exam paper at the end and it tells you exactly where you are.”

This, however, remains the mock exam. The main event will be at the Emirates on August 17 — and if Wolves are leading with two minutes to go, O’Neil will know his plan has come together.

(Photos: Wolves; design: Dan Goldfarb)

Sports

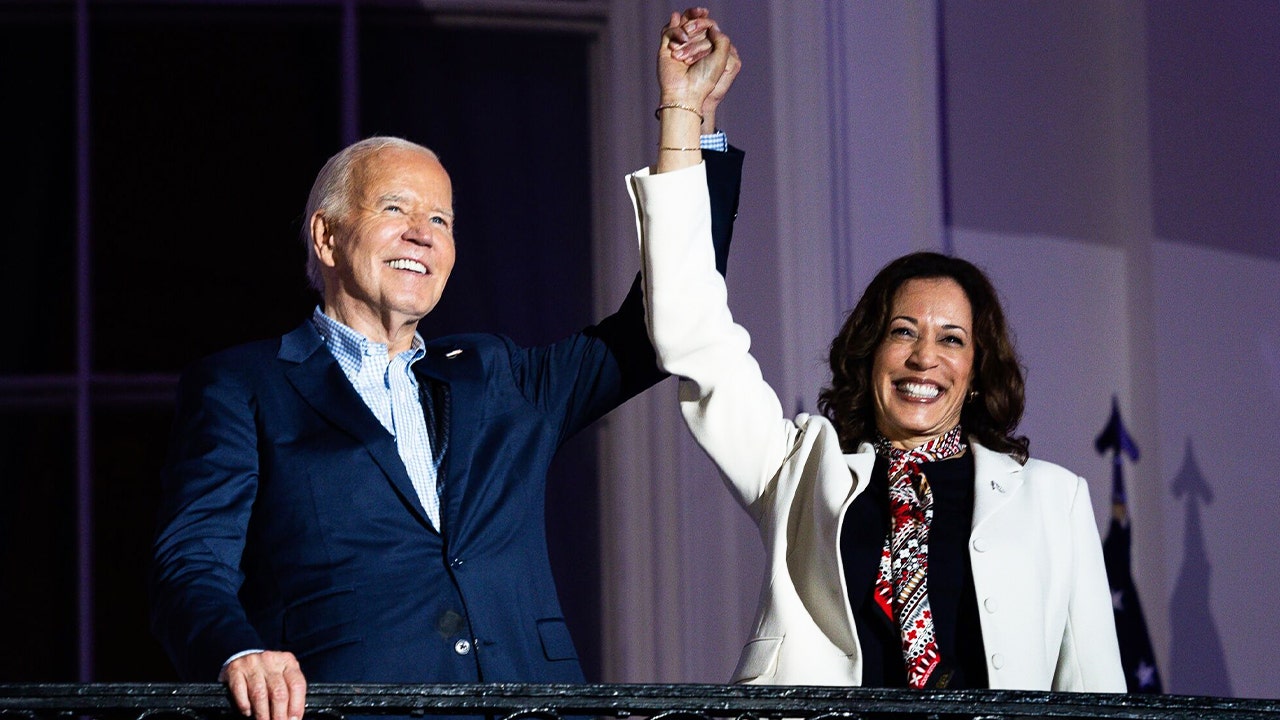

Dodgers face 'sense of urgency and competition' with roster for the rest of the season

The “calvary,” as Dodgers manager Dave Roberts put it this weekend, is coming.

Which means not everyone in the team’s current stable is likely to keep their spot.

In recent weeks, much of the external attention on the Dodgers has revolved around their shrinking cushion in the National League West standings, where a lead once as large as nine games has been trimmed down to 4½ by the San Diego Padres (and five by the Arizona Diamondbacks) entering Monday’s games.

Inside the clubhouse, however, urgency is emanating from a different source — with a wave of trade deadline arrivals and soon-to-return members of the injured list creating pressure through a roster math problem.

The Dodgers are, essentially, facing a sort of baseball Darwinism the rest of the season — with a bloated roster likely to be trimmed down the stretch, and a number of players uncertain to make the final cut.

“There should be a sense of urgency and competition,” Roberts said Sunday, adding: “We’ve got more guys coming than we have spots.”

Most position groups figure to apply.

For example, the Dodgers have three left-handed-hitting outfielders — Jason Heyward, James Outman and the newly acquired Kevin Kiermaier — on a team that, at full strength, will only need two at most (and maybe just one if Mookie Betts or Tommy Edman see significant outfield time once they return from the injured list).

The club has six utility players — Edman, Kiké Hernández, Amed Rosario and Cavan Biggio on the active roster; Chris Taylor and Miguel Rojas on the injured list — for maybe only three or four ultimate spots.

Same story in the bullpen, where the Dodgers currently have eight arms that have all pitched leverage innings this year, but also three rehabbing relievers nearing returns (Brusdar Graterol and Michael Grove could be back as soon as this week’s homestand; Ryan Brasier isn’t far behind them), plus an unsettled closer’s role.

Even the rotation remains an ever-changing battle; both for depth spots among rookie pitchers (River Ryan, Landon Knack and Justin Wrobleski have all cycled through this year), and coveted potential postseason starts (especially if Yoshinobu Yamamoto returns from his shoulder injury in September, as Roberts said this weekend he expects).

“It should be a meritocracy,” Roberts said. “At some point, the rubber meets the road, and we’ve got to make some tough decisions.”

For some players, improvement might come naturally.

A month ago, Gavin Lux looked destined for a diminished late-season role. Some rival executives wondered if he could wind up on the trade block.

Instead, Lux has turned into one of the team’s best hitters over the last four weeks, batting .386 in his last 19 games (with nine extra-base hits and 15 RBIs) while bumping up to the No. 3 spot in a shorthanded batting order.

“I think you feel that pressure a little bit, but I wasn’t going out there thinking about it every day,” Lux said, pushing back on the idea his play improved as a result of roster pressure.

Others might benefit from more internal competition.

When discussing this dynamic Sunday, Roberts pointed specifically to Hernández, who might finally be turning a corner after a dismal first-half performance.

“He’s playing his best baseball that he’s played in a while, on both sides of the ball,” Roberts said of Hernández, who is batting .300 since the All-Star break with five doubles and eight RBIs. “No. 1, he’s playing good baseball. But I also feel that he’s smart enough to realize that there’s other guys that are coming. And how do you keep getting opportunities? You perform.”

Following his two-double performance Sunday, Hernández insisted he wasn’t overly worried about his place on the roster.

“It is what it is,” he said. “I’m not really thinking about that. That’s out of my control.”

At the same time, however, Hernández acknowledged the pressure he feels to perform — both as it relates to his personal goals, and also the overall outlook of the club.

“This game is about producing, or you’re gonna be out of the game,” he said. “Just trying to do my part. We’ve been struggling as a team, and I believe that if I’m anywhere close to the hitter that I’m capable of being, we’d be in better shape and a better spot.”

Indeed, this might be the best path forward for the Dodgers to rectify their top-heavy roster problems.

Instead of adding another everyday bat to the lineup at the trade deadline — the team didn’t meet asking prices for potential targets, including Randy Arozarena of the Tampa Bay Rays and Luis Robert Jr. of the Chicago White Sox — the club loaded up on depth and versatility.

As a result, they now have 18 position players on their 40-man roster with extensive MLB experience, for only 13 available roster spots once they reach the playoffs.

Those additions were necessary in the short term, putting Band-Aids on many of the Dodgers’ injury-induced shortcomings.

“It’s trying to weather or withstand a regular season,” Roberts said. “So you have to kind of backfill.”

But once everyone gets back, there will be important personnel choices for the Dodgers to make leading up to October.

Their hope is that, between now and then, the cream of their depth chart will rise to the top.

“That’s the way it should be,” Roberts said. “That’s a good thing for the organization.”

Sports

What makes Leon Marchand a superstar? He's smaller, lighter and unbelievable underwater

Leon Marchand is an enigma.

Over the past eight days, he has produced one of the best Olympic pool displays. It featured an unprecedented double gold in the 200m breaststroke and 200m butterfly.

Only one athlete had ever made the final in both strokes over any distance. That was Mary Sears in 1956, with the American winning bronze in the 100m butterfly and finishing seventh in the 200m breaststroke.

Marchand, who also won the 200m and 400m individual medleys, took four individual golds in four Olympic record times. Those performances are not normal, even by elite standards. The 22-year-old is the fourth swimmer and first French Olympian with four individual golds in one Games — joining the United States’ Mark Spitz (1972), East Germany’s Kristin Otto (1988) and the U.S.’s Michael Phelps (in 2004 and 2008).

The Marchand-Phelps comparisons write themselves. Marchand’s coach at Arizona State University, Bob Bowman, previously coached Phelps. In early 2023, Bowman said, “Leon is reminding me of Michael in 2003.” Bowman was talking about what Leon swam, not how he swam it, praising his ability to produce fast race times despite high training volumes.

Physically, Marchand is more like Spitz than Phelps. Phelps is six centimetres (2.4in) taller (193cm versus 187cm) and raced seven kilograms heavier (84kg compared to 77kg) than the Frenchman. Marchand isn’t matching the American’s 79-inch wingspan. Part of Marchand’s allure is how he bucks the trend of Olympic swimmers getting bigger and taller.

GO DEEPER

Meet Léon Marchand, the ‘French Michael Phelps’ ready to rule his home Olympics

A 2020 paper collated nine studies analysing Olympic swimmers between 1968 and 2016. It was “advantageous for swimmers to be older, taller, and heavier”. From Mexico City in 1968 to Rio de Janeiro in 2016, world-class men’s 200m swimmers (Marchand’s favourite distance) changed drastically: on average, they became 8.6cm taller and 7.9kg heavier.

The authors of that paper spoke of the “natural selection” of athletes into events based on their body types and suitability for strokes. Freestyle swimmers were the biggest, all about power and big, long limbs. Butterfly swimmers were the smallest, with back and breaststroke swimmers in the middle. Imagine a Venn diagram where Phelps sits in the overlapping free/fly/back rings, and Marchand in breast/fly/back.

Francisco Cuenca-Fernandez, a PhD graduate from the aquatics lab at the University of Granada and a professor with a research specialism in race analysis, explains how Marchand’s atypical size is advantageous.

“Swimmers are usually large because a large body is associated with a long lever arm, which is very beneficial as it allows propulsive surfaces, like the hands, to stay underwater longer, applying force.”

But that bulk is a double-edged sword. “This has a downside,” says Cuenca-Fernandez. “A large body can also generate much more resistance. In Marchand’s case, his events have always been middle-distance — the 200m and 400m — which indicates that a large, muscular body would have been very energy-consuming.

“We haven’t seen him compete individually in the 100m butterfly or 100m breaststroke and he hasn’t stood out in his freestyle relay performances either. He is a swimmer who doesn’t stand out for his height or musculature, but this makes him incredibly efficient.”

Efficiency.

It was the difference between Marchand and Hungary’s Kristof Milak in the 200m butterfly final, where sprint specialist Milak led at 150m but Marchand’s back-end speed saw him close hard. Cuenca-Fernandez uses that word repeatedly to describe Marchand.

“He moves easily and this saves a lot of energy. This is where he’s making the difference,” says Cuenca-Fernandez, who roots Marchand’s efficiency in a combination of his training under Bowman and innate physiology, a virtue of having former Olympian parents.

It is how Marchand breaks his opponents in the medley, with his strongest strokes first (fly) and third (breaststroke) and his weakest second (back) and last (free). “This efficiency is maximized in butterfly and breaststroke, which are strokes where it’s challenging to maintain cadence since the body is constantly accelerating and decelerating, leading to quick fatigue,” says Cuenca-Fernandez.

Marchand in the semi-final of the 200m butterfly event in Paris (Sebastien Bozon/AFP via Getty Images)

Breaststroke is leg-dominant, too, so guys with big upper bodies and wingspans benefit less. “It’s evident that his race strategy is based on being strong in these two strokes,” says Cuenca-Fernandez, explaining that Marchand’s natural strengths work tactically.

“Start strong in butterfly, using powerful undulation (wave-like movements with the body). In backstroke, maintain position, since I can breathe much more easily than in the other strokes. In breaststroke, I take advantage of my underwater efficiency, both in the underwater phase after pushing off the wall and the gliding phase, and push hard again. In freestyle, I give whatever I have left, less fatigued than others.”

Marchand’s efficiency — combined with elite conditioning — makes him so good underwater. He glides and kicks like nobody else. In the 200m breaststroke final, he was 1.8m up on second-place Zac Stubblety-Cook at the final turn but stayed underwater for so long that he surfaced after his nearest opponent even further in the lead.

In the 400m individual medley, Marchand spent 100m of that gliding underwater, around one-fifth more than his opponents — Phelps spent 77m underwater in the same race in Beijing in 2008. Marchand spent 14.77m of the allowed 15m underwater off the final turn when he set the 400m individual medley world record in Japan last year.

“That incredible underwater swimming is a characteristic of swimmers trained by Bowman,” says Cuenca-Fernandez. Even Phelps is astounded by Marchand’s glides. Bowman once said they were “not a subject, they have always been excellent”. Marchand is built to swim underwater, with what Bowman calls a torpedo-like body and “no hips”.

Cuenca-Fernandez says: “The depth of his underwater undulation stands out — this trajectory towards the bottom of the pool after the push-off from each turn.

“This provides an advantage — as long as you have the lungs for it — the reduction of wave resistance. When a group of swimmers reach the wall at full speed to turn, there is a mass of water dragged that ends up crashing against the wall.

“If your turn is too close to the surface and you are a little ahead of your competitors, that mass of water hits you just as you are flipping or starting your push-off and slows you down. However, if after your turn you go to the bottom of the pool, that mass of water passes over you and you manage to avoid it.”

It depends on the athlete — specifically their build and strength in swimming on the surface — but underwater swimming is typically faster as turbulence and drag are reduced (although this doesn’t apply to free, where surface swimming is faster than back, fly and breaststroke).

In one of Cuenca-Fernandez’s studies, assessing performance variability of swimmers going through championship rounds, they identified that the push-off in the first five metres from the turns was the only consistent variable. Things like stroke volume, start, and underwater kick all changed.

“The ones who reached the finals were always faster, they had better underwater gliding skills and offered less resistance,” he says. “The speed of that push-off was always the same for a given swimmer. I’m sure that if we analyze Marchand in depth, he would be one of the fastest at that point since he is a swimmer who generates very little resistance.”

Marchand’s style is something psychologists call an underdog effect — when athletes succeed despite disadvantages. Often these are sociocultural, economic or geographical, none of which apply to Marchand, but he is a fourth-quartile baby (May) and, physically, matured late.

Santiago Veiga Fernandez, a former head coach of the Spanish Swimming National Youth Team, with a PhD in swimming race analysis, explains it. Marchand, he says, benefitted from “great developmental work” by his French home coach Nicolas Castel from the Toulouse Dolphins club. During his junior years — 16 to 18 — Marchand developed the basic skills that allowed him to excel underwater.

“When competing at European or World Junior Championships, Marchand did not dominate. He was a bronze medallist at a couple of events (European bronze in 200m breaststroke and 400m individual medley; world bronze in 400m individual medley). His body was not fully developed, but he already showed great levels of skill for gliding and underwater swimming.”

He had to be good at gliding underwater — he didn’t have freestyle power or speed anywhere near that of Phelps. Marchand’s 100m free personal best is almost four seconds slower, although he’s a better freestyler than Phelps was a breaststroker (Marchand’s 200m personal best at breaststroke is more than five seconds faster than Phelps’).

Scheduling is a significant reason the breaststroke/fly double is unique, as they happen in the same evening session, which forces specialism in one (World Aquatics actually had to change the Olympic schedule to let Marchand attempt it).

Another reason, Veiga explains, is technique differences. “The kicking action in butterfly and breaststroke are quite the opposite and swimmers with a great range of motion in one stroke may not excel in the other.

“In breaststroke, you can only perform one underwater dolphin kick after diving off the block or pushing off the turning wall, whereas in butterfly, swimmers can perform multiple underwater dolphin kicks.”

These kicks require the feet to flex in different ways (because the arm strokes are different). It might seem small, but at the highest level, details make performance differences.

Marchand in the butterfly heats (Quinn Rooney/Getty Images)

And in the breaststroke final, emphasising the difference in technique (Ian MacNicol/Getty Images)

Given his exponential progression since Tokyo, the thoughts of where Marchand might be in four years are scary. Improve his freestyle and the world records will tumble. Veiga says that the 200m breaststroke showed Marchand becoming a versatile racer, as he swam hard from the off to compensate for Stubblety-Cook’s fast final 50m, rather than winning it late himself.

Ultimately, Marchand has put French swimming in a better place. They didn’t take a gold in the pool at the last two Games and managed four medals combined in Tokyo and Rio de Janeiro, as many as Marchand has in Paris alone.

France’s golden boy has changed the face of swimming. There’s more than one way to win an Olympic gold. Or four…

(Top photo: Adam Pretty/Getty Images)

-

Mississippi6 days ago

Mississippi6 days agoMSU, Mississippi Academy of Sciences host summer symposium, USDA’s Tucker honored with Presidential Award

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoRepublicans say Schumer must act on voter proof of citizenship bill if Democrat 'really cares about democracy'

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoHe raped a 12-year-old a decade ago. Now, he’s at the Olympics

-

World1 week ago

More right wing with fewer women – a new Parliament compendium

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump announces to crowd he 'just took off the last bandage' at faith event after assassination attempt

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoItaly's Via Appia enters the Unesco World Heritage List

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoIsrael says Hezbollah crossed ‘red line’, strikes deep inside Lebanon

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoSonya Massey death brings fresh heartache to Breonna Taylor, George Floyd activists