Lifestyle

How to accept being 'a fat person' and quiet your inner critic

As an only child who moved around a lot, Emma Specter learned to comfort herself, as a lot of kids do, with familiar foods — whether it was the Dunkin Donuts she sought out in Rome or the candy bars she stock-piled from Manhattan bodegas. By the time she entered high school, she’d begun using food as more than just a source of soothing, but as a kind of numbing agent she’d administer in secret. Mindlessly eating cookie dough to the point of physical discomfort, she discovered, could help ease the pain of life’s most unpleasant moments — that is, until the shame set in, followed by an urge to count calories.

Shelf Help is a new wellness column where we interview researchers, thinkers and writers about their latest books — all with the aim of learning how to live a more complete life.

Specter eventually came to identify this behavior as bingeing, an eating disorder she describes viscerally in her memoir, “More Pease: On Food, Fat, Bingeing, Longing, and the Lust for ‘Enough’” (HarperCollins). Bingeing can look different for different people, but for Specter, it involves “shoving food furtively into my mouth as quickly and passively” as possible, she writes. Her debut book, which pairs a deeply personal (and often humorous) narrative with academic research and journalistic inquiry, explores the origins of her disordered eating while also searching for a motive: “Why do I do this?” Specter said in an interview.

The Los Angeles-based Vogue culture writer is still trying to answer that question. In addition to lots of therapy and introspective writing, her process so far has been to interview writers, scholars and fat activists about diet culture and its societal underpinnings.

The Times spoke to Specter about how she realized she had an eating disorder, why she decided to ditch dieting and what happened when she began to reframe her thinking about her body.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

In your book, you describe how any sort of event in your life — no matter how big or small — could trigger a binge. What did this pattern look like for you and how did you recognize that it was part of a disorder?

I definitely was and still am more likely to binge on a bad day than a good one, but sometimes something very minor would go wrong and I would react by bingeing. When I’m in a bad mood or bored or lonely or tired, it’s hard for me to self-regulate without food. I think a lot of us use food for comfort and that doesn’t have to look like a disordered attachment. But for me, it was very much about shutting out the world with food.

I think that’s the tricky thing, too, is that obviously everyone eats food for survival, for comfort, for all of these things. Was there a moment where you recognized, ‘Oh, what I’m doing is maybe a little bit destructive,’ if that’s how you see it?

Absolutely, that is how I see it. When I was in my early to mid-20s, I started to recognize that something was off. A lot of things that I had desperately wanted came to fruition. I had jobs in media, I had a big group of friends, I came out [as queer], dating was better and more exciting, or at least existent. But I felt like there was this real disconnect where I started bingeing almost more once I had more in my life. I was more fulfilled and happy, but still bingeing and then realizing, ‘What function is this playing for me? And is it an escape when I’m feeling overwhelmed or scared or stressed about the stakes of my new life?’

Right. How do you work toward not relying on food so much as an escape from your feelings?

I’ve found a lot of beauty in communal meal-making and eating together with my partner and their roommates and my friends and just reminding myself that food can absolutely be this huge source of comfort when I’m feeling overwhelmed, and it doesn’t have to go along with solitude and hiding.

When I was in the diet-binge cycle that I was in for so long, I was very concerned about ‘How am I going to have a group dinner with friends and still stick to my Weight Watchers points?’ I’m thrilled to say that I haven’t dieted in a long time, but that lizard brain mentality is still with me sometimes telling me what I should and shouldn’t be eating or enjoying. The more that I can come together with other people around food, the less I feel like it has to be this solitary kind of respite that I only engage in in a disordered way.

So the journey you describe in the book is twofold: You’re recognizing that you’re bingeing and figuring out what’s behind it and how to manage it, but you’re also learning to abandon diet culture. Do you feel like those two things go hand in hand?

Absolutely. I do think giving up dieting was really crucial to getting to a place where I can just accept myself as a fat person. It was truly one of the most ingrained habits of my life to the point where — I think as so many people, and especially women — do, I still know the caloric value for foods and I’m trying to chase that out of my brain. It doesn’t hurt to know what’s in your food, but I’m trying to chase away the sense of “Oh, my god, this banana has so-and-so calories, I can’t have it.” I think saying goodbye to dieting has really been crucial in just accepting the body that I have now and not the body that I could have if I cut out carbs and worked out for two hours every day.

I was a little disappointed that quitting dieting didn’t fix my bingeing, which maybe should have been obvious to me because bingeing is a very ingrained habit that I’ve been engaging in over the course of my life. But part of me thought that if I’m not dieting anymore then I won’t ever have the urge to overindulge. It can be demoralizing to feel like I’m doing all this work [toward having a positive relationship with food] and still I find myself bingeing, but I think that’s just part of the balance — especially in the place that I’m at in my recovery, which centers very much around harm reduction. I’ve made a tenuous peace with the idea that bingeing is going to be a part of my life.

You write about your bingeing as a form of self-harm, about the way it caused you shame and embarrassment, nausea and indigestion. Could you talk about some of the other ways it affected and still affects your life?

Something I want to highlight is just the amount of money that I spent on binge food. Obviously it was not a ton — an individual binge could be a thing of ice cream, which costs $7, but that stuff adds up — and it’s not my favorite use of money. It’s not my favorite use of how to engage with the world and the economy, especially through the use of food delivery apps. Being dependent on somebody else’s precarious labor to bring you food you don’t even want doesn’t feel great and it isn’t the way that I want to engage with my community.

I also think for a long time, I felt like my consequences, for lack of a better word, were fatness. I remember at a certain point catching a glimpse of myself in the mirror after I gained weight and thinking, ‘Look what you’ve done to yourself.’ You know, just really unkind self thoughts that I try really hard not to harbor anymore, but they sneak in ‘cause we live in a fat-phobic society. But I do think it has been a really beautiful reframe to just be like, my body is not a negative outcome and it’s not a consequence of anything. It’s just my body and it can do a lot of incredible things.

TAKEAWAYS

from “More, Please”

Reading your book, it’s obvious that you didn’t arrive at body acceptance overnight, and that it’s still a work-in-progress. Can you talk about what has helped you become kinder to yourself along the way?

I can’t think of something that has had a bigger impact on me than having fat friends. Just being surrounded by fat people who love each other and are loved — which sounds so corny — but I just think it gives me a script every day for my own self-acceptance. I can’t overstate the importance of having fat community in my life, and I really hope that for every fat person.

I know that being fat can be tricky because it can often feel like it’s your rest stop on the road to thinness, but I have felt so deeply that if I want to live in my body happily as it is, I need to surround myself with other people who do that and who accept themselves and who still have difficult moments and who have journeys that I might not necessarily even know about because every single person is going through their own world and journey in their own meat suit.

What advice would you give to someone who wants to start re-evaluating their relationship with food or with their body?

Try not to be alone with it. “It” being your fear and your anxiety over what you’re eating or not eating or what your body looks like or doesn’t look like. Sometimes that means talking to people in your life, but I think people dealing with disordered eating and binge eating in particular can often feel so much shame that it’s really hard to start that conversation. In your Notes app or your Google Docs is as good as any place to start a conversation, even just with yourself while you’re figuring out what another level of help might look like for you.

I just hope, as corny as this sounds, that you’re as nice to yourself as you can summon the ability to be in the process of finding your version of therapy, or writing about your issues, or talking to your loved ones about what’s going on with you. None of that is possible without this little glimmer of self-compassion, and the self-compassion has to be first.

(Maggie Chiang / For The Times)

Shelf Help is a wellness column where we interview researchers, thinkers and writers about their latest books — all with the aim of learning how to live a more complete life. Want to pitch us? Email alyssa.bereznak@latimes.com.

Lifestyle

In a first-of-its-kind decision, an AI company wins a copyright infringement lawsuit brought by authors

The Anthropic website and mobile phone app are shown in this photo on July 5, 2024. A judge ruled in the AI company’s favor in a copyright infringement case brought last year by a group of authors.

Richard Drew/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Richard Drew/AP

AI companies could have the legal right to train their large language models on copyrighted works — as long as they obtain copies of those works legally.

That’s the upshot of a first-of-its-kind ruling by a federal judge in San Francisco on Monday in an ongoing copyright infringement case that pits a group of authors against a major AI company.

The ruling is significant because it represents the first substantive decision on how fair use applies to generative AI systems.

Fair use doctrine enables copyrighted works to be used by third parties without the copyright holder’s consent in some circumstances such as illustrating a point in a news article. Claims of fair use are commonly invoked by AI companies trying to make the case for the use of copyrighted works to train their generative AI models. But authors and other creative industry plaintiffs have been pushing back with a slew of lawsuits.

Authors take on Anthropic

In their 2024 class action lawsuit, authors Andrea Bartz, Charles Graeber and Kirk Wallace Johnson alleged Anthropic AI used the contents of millions of digitized copyrighted books to train the large language models behind their chatbot, Claude, including at least two works by each plaintiff. The company also bought some hard copy books and scanned them before ingesting them into its model.

“Rather than obtaining permission and paying a fair price for the creations it exploits, Anthropic pirated them,” the authors’ complaint states.

In Monday’s order, Senior U.S. District Judge William Alsup supported Anthropic’s argument, stating the company’s use of books by the plaintiffs to train their AI model was acceptable.

“The training use was a fair use,” he wrote. “The use of the books at issue to train Claude and its precursors was exceedingly transformative.”

The judge said the digitization of the books purchased in print form by Anthropic could also be considered fair use, “because all Anthropic did was replace the print copies it had purchased for its central library with more convenient space-saving and searchable digital copies for its central library — without adding new copies, creating new works, or redistributing existing copies.”

However, Alsup also acknowledged that not all books were paid for. He wrote Anthropic “downloaded for free millions of copyrighted books in digital form from pirate sites on the internet” as part of its effort “to amass a central library of ‘all the books in the world’ to retain ‘forever,.’”

Alsup did not approve of Anthropic’s view “that the pirated library copies must be treated as training copies,” and is allowing the authors’ piracy complaint to proceed to trial.

“We will have a trial on the pirated copies used to create Anthropic’s central library and the resulting damages, actual or statutory (including for willfulness),” Alsup stated.

Bifurcated responses

Alsup’s bifurcated decision led to similarly divided responses from those involved in the case and industry stakeholders.

In a statement to NPR, Anthropic praised the judge’s recognition that using works to train large language models was “transformative — spectacularly so.” The company added: “Consistent with copyright’s purpose in enabling creativity and fostering scientific progress, Anthropic’s large language models are trained upon works not to race ahead and replicate or supplant them, but to turn a hard corner and create something different.”

However, Anthropic also said it disagrees with the court’s decision to proceed with a trial.

“We believe it’s clear that we acquired books for one purpose only — building large language models — and the court clearly held that use was fair,” the company stated.

A member of the plaintiffs’ legal team declined to speak publicly about the decision.

The Authors’ Guild, a major professional writers’ advocacy group, did share a statement: “We disagree with the decision that using pirated or scanned books for training large language models is fair use,” the statement said.

In an interview with NPR, the guild’s CEO, Mary Rasenberger, added that authors need not be too concerned with the ruling.

”The impact of this decision for book authors is actually quite good,” Rasenberger said. “The judge understood the outrageous piracy. And that comes with statutory damages for intentional copyright infringement, which are quite high per book.”

According to the Copyright Alliance, U.S. copyright law states willful copyright infringement can lead to statutory damages of up to $150,000 per infringed work. The ruling states Anthropic pirated more than 7 million copies of books. So the damages resulting from the upcoming trial could be huge.

The part of the case focused on Anthropic’s liability for using pirated works is scheduled to go to trial in December.

Other cases and a new ruling

Similar lawsuits have been brought by other prominent authors. Ta-Nehisi Coates, Michael Chabon, Junot Díaz and the comedian Sarah Silverman are involved in ongoing cases against AI players.

On Wednesday, U.S. District Judge Vince Chhabria ruled in favor of Meta in one of those cases. A copyright infringement lawsuit was brought by 13 authors including Richard Kadrey and Silverman. They sued Meta for allegedly using pirated copies of their novels to train LLaMA. Meta claimed fair use and won because the authors failed to present evidence that Meta’s use of their books impacted the market for their original work. However, the judge said the ruling applies only to the specific works included in the lawsuit and that in future cases, authors making similar claims could win if they make a stronger case.

“ These rulings are going to help tech companies and copyright holders to see where judges and courts are likely to go in the future,” said Ray Seilie, a lawyer based in Los Angeles with the firm Kinsella Holley Iser Kump Steinsapir, who focuses on AI and creativity. He is not involved with this particular case.

“ I think they can be seen as a victory for the AI community writ large because they create a precedent suggesting that AI companies can use legally-obtained material to train their models,” Seilie said.

But he said this doesn’t mean AI companies can immediately go out and scan whatever books they buy with impunity, since the rulings are likely to be appealed and the cases could potentially wind up before the Supreme Court.

“ Everything could change,” Seilie said.

Lifestyle

The world's largest wildlife crossing is entering Stage 2: What's that mean for traffic?

When you’re trying to build a mountain over one of the country’s busiest freeways, it’s easy to be envious of original creation stories, when natural spaces were formed with just a wave of the hand.

In those stories, there were no overhead wires to bury or water lines to move. There weren’t vehicles to divert, underground creeks that required stabilization, majestic oaks that had to be saved or soils that required inoculation with local microbes.

But such are the looming challenges for the designers and builders of the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing, the world’s largest and most ambitious crossing designed to give wildlife a safe and nature-mimicking passage over the 10-lane 101 Freeway in Agoura Hills.

The crossing structure itself is mostly completed — except the planting, which will happen this fall — but it’s basically a bridge to nowhere right now, squatting over the freeway just west of the Liberty Canyon Drive offramp. (Although — news flash! — even though it’s not connected to the neighboring hills, the first non-insect wildlife was spotted on the bridge last week: a Western fence lizard basking at the top, roughly 75 feet above the traffic below.)

The second and final phase is installing the connectors — the structure’s shoulders that will permit freeway-fragmented wildlife to easily cross between the Santa Susana Mountains to the north and the Santa Monica Mountains to the south.

Expanding the areas where wildlife can safely roam will increase their chances of finding mates while improving the health and genetic diversity of everything from lizards to mountain lions like P-22, whose lonely life in Griffith Park helped inspire the crossing.

This second phase is the trickiest part of the project, especially the south-side connection over Agoura Road, according to Robert Rock, chief executive of Chicago-based Rock Design Associates and the landscape architect overseeing the $92.6-million project.

The Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing connector to the south will be supported by a tunnel over Agoura Road, which will roughly be located between the two white trailers in the photo and then threaded (as much as possible) around the small grove of mature oak trees into the Santa Monica Mountains beyond.

(Jeanette Marantos)

Work on the south side requires burying overhead wires near the site, moving water lines for the Las Virgenes Municipal Water District, stabilizing an underground creek (dubbed No-Name Creek) that runs under the tunnel site to prevent erosion and then driving two walls of pilings deep into the ground for 175 feet along Agoura Road to build the 54-foot-wide tunnel that will span the road.

Once the tunnel is constructed and the concrete roof is poured, workers will literally be moving a small mountain of soil from the north side of the freeway, where it was piled when this stretch of the 101 was constructed in the 1950s, to cover the tunnel and create the sloping connecting shoulder into the Santa Monica Mountains.

The final work will be planting more native shrubs, perennials and trees on the shoulders and adding two miles of galvanized steel fencing on either side of the crossing to funnel animals over the crossing and away from human-made roadways and homes.

Easy peasy, right? Except for one more detail — they have to do all this building and earth moving without disturbing a sprawling grove of native oak trees growing around the site.

The designers plan to thread their way through the small grove of mature oaks on both sides of Agoura Road to preserve as many of the mature trees as possible when building the south shoulder of the crossing over the road and into the Santa Monica Mountains.

(Christina House / Los Angeles Times)

“It’s a tricky pocket,” said Rock. “We’re definitely threading a needle.”

Some of the smaller trees may have to be removed, he said, but the designers are doing everything they can to maintain the native trees growing around the site. Not surprising, because the whole project has focused on re-creating nature as much as possible on a foundation of concrete and steel, with native plants grown from seeds collected within a three-mile radius of the project and soil specially inoculated with local fungi and microbes to enhance their growth. The plants are being tended at the project nursery a few miles from the site.

C.A. Rasmussen Inc., the Valencia-based contractor who built the first phase of the project, has won the bid to do the second stage as well, said Rock. Weather delays — primarily from heavy rains in 2022 and 2023 — have pushed the crossing’s final completion date to the end of 2026. The state of California has provided $58.1 million of the $92.6-million project, as part of its “30 by 30” goal to conserve 30% of the state’s lands and coastal waters by 2030. The rest of the funds are coming from private donations.

Work on the final phase is expected to begin next week. Much of the prep work and tunnel construction will require at least a partial closure of Agoura Road, but the builders have to give 30-days notice before the closures begin.

Artist renderings of how the tunnel over Agoura Road and the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing will look to the south, heading toward the Santa Monica Mountains, when the crossing is completed at the end of 2026. The top view is facing east on Agoura Road, the bottom view is looking west.

(Rock Design Associates and National Wildlife Federation)

(Rock Design Associates and National Wildlife Federation )

The specific closure hours are still being negotiated with the city of Agoura Hills, but Rock said he expects Agoura Road will be only partially closed to vehicle and bike traffic during daytime hours, when the contractor will be working. The closures are expected to begin in early August, and last for “several months,” he said.

“I can’t really say [how long] beyond several months’ worth of impacts,” he said, “but I hope we can be done by the end of the year.”

A few plants are already beginning to grow on the main structure, from a special cover crop of four native plants hand-sown in the spring — golden yarrow (Eriophyllum confertiflorum), California poppy (Eschscholzia californica), giant wildrye (Elymus condensatus) and Santa Barbara milk vetch (Astragalus trichopodus), chosen because they best flourished with the mycorrhizal fungi and other microbes added to the soil.

Last week, at least one invasive black mustard plant was also visible on the crossing — not surprising since the surrounding hills were lush with the fast-growing, easily spread mustard earlier this spring — but contractors are supposed to keep those invasive plants weeded out, Rock said, to give the natives a chance to get established.

Hundreds of native plants that were grown from seed in the project’s nearby nursery will be planted on the crossing this fall, probably in October, said Beth Pratt, California regional executive director of the National Wildlife Federation and leader of the Save LA Cougars campaign, who is overseeing funding and fundraising for the project.

The top of the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing resembles a reddish Marscape now, although a cover crop of native plants — California poppy, giant wild rye, Santa Barbara milk vetch and golden yarrow — hand sown from seed this spring are starting to emerge. Hundreds of larger native shrubs and perennials, grown from seed in the project’s nearby nursery, will be planted on the crossing in October.

(Christina House / Los Angeles Times)

Save LA Cougars is selling a blend of six native seeds provided by Pacific Coast Seed (formerly S&S Seed) for people who want bragging rights to growing six of the native plants that will feature prominently on the crossing — common deerweed (Acmispon glaber var. glaber), ashyleaf buckwheat (Eriogonum cinereum), showy penstemon (Penstemon spectabilis), black sage (Salvia mellifera), narrow leaf milkweed (Asclepias fascicularis) and foothill needlegrass (Stipa lepida)

You can order a packet of the souvenir seeds online for $10. Proceeds will support the project’s nursery, which is featured in a new Save LA Cougars video explaining how all the crossing’s native plants, soils and compost have been chosen and nurtured.

In the meantime, the recent tariffs have added a new funding concern for the project. It’s not clear yet if the project will need to do more fundraising to cover all the increased costs, Pratt said.

“Robert [Rock] and CalTrans have been working around the clock to redesign and value-design to get the costs down, which is why we’re able to proceed [with Stage 2],” Pratt said. “The team work has been extraordinary.”

It’s possible they may need to raise more money to cover final expenses like the two miles of extra-tall fencing that Rock estimates will cost around $2 million, but right now, Pratt said, the design adjustments seem to have contained the extra costs. “They got them down again, so I think we’re home free.”

Meanwhile, while all these human issues are unfolding, somewhere on top of the unfinished crossing that Western fence lizard appears to be making a home, even though the naked terrain looks like a moonscape right now. Pratt was leading a small group of visitors when she spotted the little reptile, and it took her a moment to process its import.

“I see Western fence lizards all the time in my yard and they are everywhere — one of the most common animals you will see in California,” Pratt wrote in an email. “But then it hit me, ‘Wait. This lizard is on the bridge!!!!! And this is the first animal I have seen on the bridge!!!!’ I stopped the group … and told them — ‘You are seeing the first animal on the crossing itself.’ Everyone cheered. Even the lizard seemed to know it was a special occasion. He posed for the photos I took.”

Lifestyle

Brother to Bruh: How Gen Alpha slang has its origins in the 16th century

A young boy holds up a sign reading “bans off her body bruh” at a rally outside the State Capitol in support of abortion rights in Atlanta, Georgia on May 14, 2022.

Elijah Nouvelage/AFP via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Elijah Nouvelage/AFP via Getty Images

Has your pre-teen child suddenly dropped the use of “Mom” or “Dad” in favor of calling you… “Bruh?” (As is the case for at least some of our editors).

While we can’t offer you compensation for the shock and confusion, we can provide an explanation of what “bruh” means and where it comes from in our latest Word of the Week.

Jamie Cohen, assistant professor of media studies at CUNY Queens College, and Amanda Brennan, known as the Internet Librarian, say we can thank social media for getting us to this point.

What was once another shortened way to call a friend “brother,” “bruh” is now being used by Gen Alpha to address parents, express sadness, frustration, happiness and seemingly everything under the sun.

“It’s punctuation. It is a sentence on its own that, depending on how you say it and who it’s said to, it can mean anything,” Brennan said.

It’s become ubiquitous thanks to TikTok, but the origins of this word, expression or what have you, go back as early as the 16th century.

Where did ‘bruh’ come from?

Over many hundreds of years, a number of words have emerged that abbreviate “brother” including “bro,” “bra” and now “bruh.” The earliest evidence of an abbreviated use of “brother” is with the word “bro,” used as early as the 16th century, said Jesse Sheidlower, former editor-at-large of the Oxford English Dictionary and an adjunct professor at Columbia University.

“Bro” usually came before “a man’s name or to a character, especially the name of an animal,” Sheidlower said. In African American folklore, we see “bro” being used in this way during the 19th century, especially in the Caribbean and Southern U.S., he said.

The first known use of the word “bruh” appeared much later, in the 1890s, according to Merriam Webster.

Back then it was being spelled “brer” and comes from the “Br’er Rabbit,” a series of stories by Joel Chandler Harris, an American journalist and folklorist who wrote these stories from the African American oral tradition, Sheidlower said.

The Brer Rabbit and Brer Fox characters are seen in the Splash Mountain attraction at Walt Disney World Resort’s Magic Kingdom on August 9, 2020, in Lake Buena Vista, Fla.

Charles Sykes/Invision/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Charles Sykes/Invision/AP

How has internet culture brought us to “bruh”

For a long time, “bruh” was put aside in favor of “bro” or “bra” (as surfers liked to call each other).

The use of “bruh” is a perfect example of how internet culture and especially TikTok, have transformed how people talk to each other, according to Brennan, who used to work at Know Your Meme, a website dedicated to documenting internet phenomena.

“I think ‘bro’ and ‘bruh’ are great examples of how words evolve over time and take their meaning so far away from what it used to be,” Brennan explained.

Guests attend TikTok Presents Something Beautiful Album Release Event With Miley Cyrus at Chateau Marmont on May 27, 2025 in Los Angeles, California.

Emma McIntyre/Getty Images North America

hide caption

toggle caption

Emma McIntyre/Getty Images North America

“Bro” walked so “bruh” could run, essentially.

It really began with the age of the 2010s meme culture, a far simpler time in our internet’s history, when the use of “bro” became widespread. While “bro” can be used as a way to refer to a friend, the internet evolved its meaning to refer to a stereotypical frat boy and their style and culture as “bro culture,” Brennan said.

Brennan herself wrote the Know Your Meme page dedicated to explaining the use of “bro.”

Phrases and memes like “U Mad Bro?” became a sensation and so did “Come at me, bro” (from Jersey Shore fame). And then you have, “Don’t Tase me, bro!” a phrase plucked from a viral video of a University of Florida student begging security officers not to Tase him during a Q&A with then-U.S. Sen. John Kerry. (They Tased him anyway.)

A short-lived app called Vine, where users watched and posted 6 second long videos that played on a loop, brought us to “bruh,” according to Cohen, the media studies professor.

Twelve years ago high school basketball player Tony Farmer collapsed after hearing his sentence in criminal court for kidnapping, assaulting and robbing a former girlfriend. A creator on Vine used this clip and put the sound effect of someone saying “bruh” as Farmer collapsed. As far as we know, that is the origin of “bruh” on the Internet, Cohen said.

Why does “bruh” matter today?

“Bruh” is popular on TikTok as users have taken the word to launch into a story, express shock, or confusion, or even to address their parents or teachers, Brennan and Cohen said.

Cohen says young watchers of TikTok are taking “bruh” and running with it.

In this photo illustration, the TikTok app is seen on a phone on March 13, 2024 in New York City.

Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images/Getty Images North America

hide caption

toggle caption

Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images/Getty Images North America

“You could probably have a complete conversation with one word just based on how you use it. It can be despair or it could be excitement or it could be just a reference,” he said.

Brennan added, “But the meaning is defined by everything happening in the moment around it, and it is a temporal word where I could say it five times a day, and each time could be like a different meaning of a sentence and it’s just one sound.”

Brennan had some advice for parents grappling with this new turn of phrase.

“Don’t be afraid of the slang. Just zoom out and think about how words are all made up by people, even the ones that aren’t slang, and read your context clues.”

-

Arizona1 week ago

Arizona1 week agoSuspect in Arizona Rangers' death killed by Missouri troopers

-

Business6 days ago

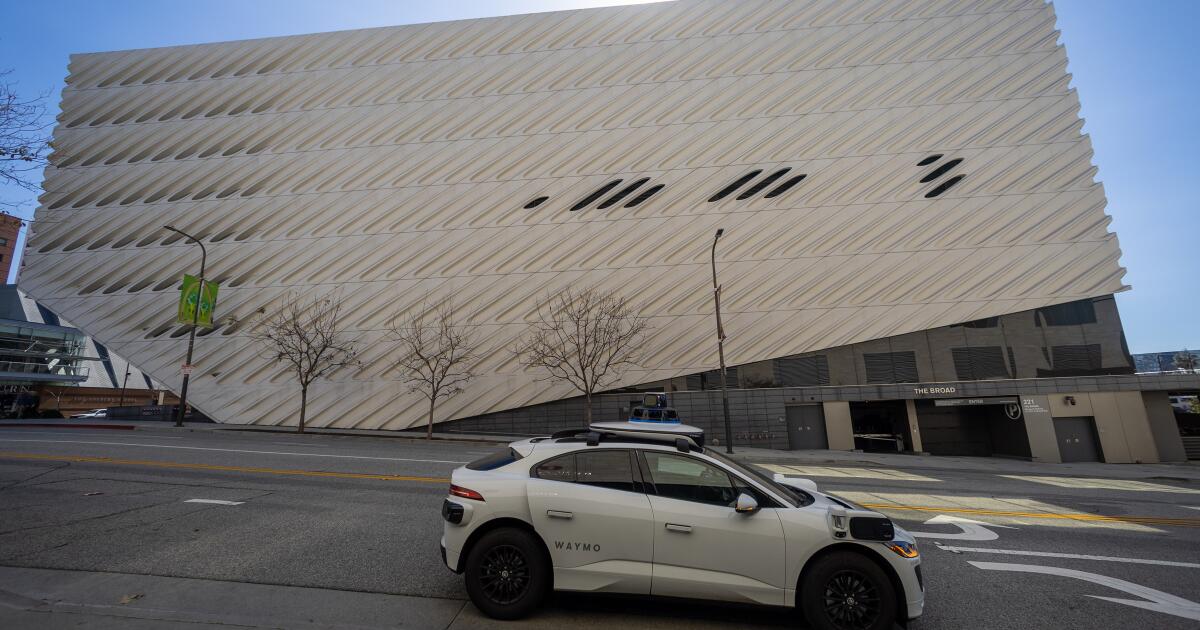

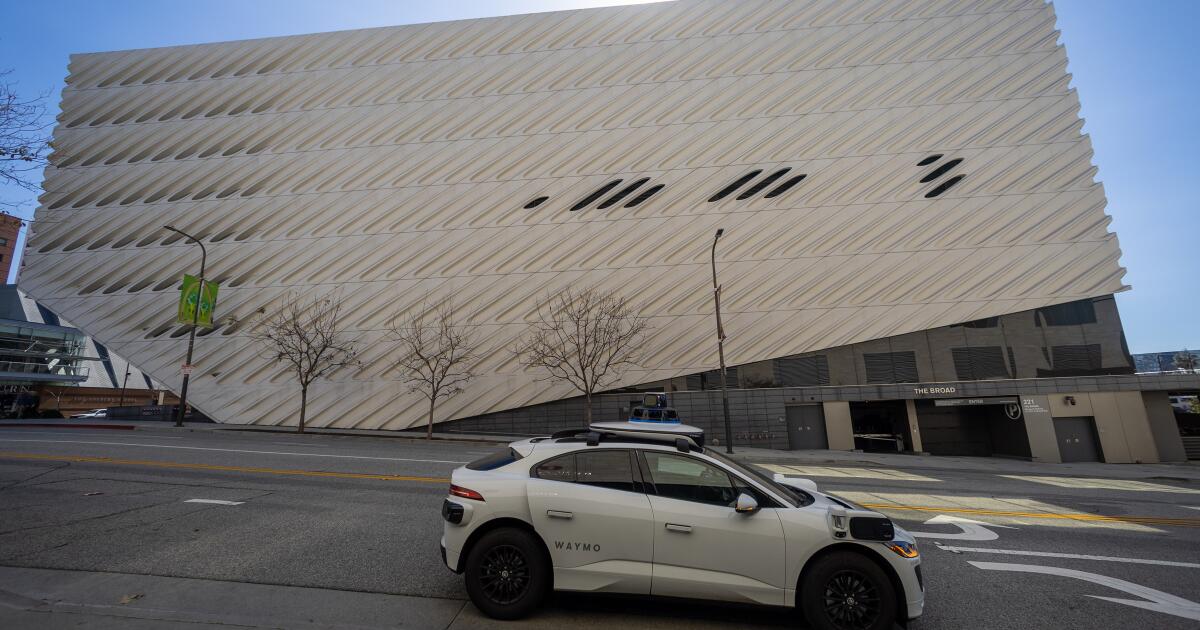

Business6 days agoDriverless disruption: Tech titans gird for robotaxi wars with new factory and territories

-

Education1 week ago

Education1 week agoJudge Delays Ruling on Trump Efforts to Bar Harvard’s International Students

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoMatch These Books to Their Movie Versions

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoWilliam Langewiesche, the ‘Steve McQueen of Journalism,’ Dies at 70

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoHow Johnson pulled off another impossible win with just 1-vote margin on $9.4B spending cut bill

-

News1 week ago

News1 week ago‘The Age of Trump’ Enters Its Second Decade

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoDog shot during Minnesota lawmaker's murder put down days after attack