Science

'Miracle' weight-loss drugs could have reduced health disparities. Instead they got worse

The American Heart Assn. calls them “game changers.”

Oprah Winfrey says they’re “a gift.”

Science magazine anointed them the “2023 Breakthrough of the Year.”

Americans are most familiar with their brand names: Ozempic, Wegovy, Mounjaro, Zepbound. They are the medications that have revolutionized weight loss and raised the possibility of reversing the country’s obesity crisis.

Obesity — like so many diseases — disproportionately affects people in racial and ethnic groups that have been marginalized by the U.S. healthcare system. A class of drugs that succeeds where so many others have failed would seem to be a powerful tool for closing the gap.

Instead, doctors who treat obesity, and the serious health risks that come with it, fear the medications are making this health disparity worse.

“These patients have a higher burden of disease, and they’re less likely to get the medicine that can save their lives,” said Dr. Lauren Eberly, a cardiologist and health services researcher at the University of Pennsylvania. “I feel like if a group of patients has a disproportionate burden, they should have increased access to these medicines.”

Why don’t they? Experts say there are a multitude of reasons, but the primary one is cost.

The injectable drug Ozempic sparked a revolution in obesity care.

(David J. Phillip/Associated Press)

Ozempic, which is approved by the Food and Drug Administration to help people with Type 2 diabetes control their blood sugar and reduce their risk of serious cardiovascular problems like heart attacks and strokes, has a list price of $968.52 for a 28-day supply. Wegovy, a higher dose of the same medicine that’s FDA-approved for weight loss in people with obesity or who are overweight and have a weight-related condition like high blood pressure or high cholesterol, goes for $1,349.02 every four weeks.

Mounjaro is a similar drug approved by the FDA to improve blood sugar levels in Type 2 diabetes patients, and it comes with a list price of $1,069.08 for 28 days of medicine. Zepbound, a version of the same drug approved for weight loss, has a slightly lower price tag of $1,059.87 per 28 days. For now, at least, all the new drugs are meant to be taken indefinitely.

Few health insurance programs cover the medications when prescribed to help people reach and maintain a healthy weight. Federal law requires that weight loss drugs be excluded from basic coverage in Medicare Part D plans, and as of early 2023, only 10 states included an antiobesity medication in the formularies for their Medicaid programs.

“If everybody had equal access, then this would be a way to help,” said Dr. Rocio Pereira, chief of endocrinology at Denver Health. “But without equal access — which is what we have now — it’s likely this is going to increase the disparity we see.”

U.S. obesity rates have been rising for decades, and they’re consistently higher for Black and Latino Americans. Among adults 20 and older, 49.9% of Black Americans and 45.6% of Hispanic Americans have a body mass index of 30 or greater, compared with 41.1% of white American adults and 16.1% of Asian American adults, according to age-adjusted data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Obesity rates are also associated with income. In 2022, the age-adjusted rate was 38.4% for adults with household incomes between $15,000 and $24,999, compared with 34.1% for those with household incomes of $75,000 or more.

The two are related, said Pereira, who studies health disparities in diseases related to obesity. Black and Latino Americans are more likely to live in lower-income neighborhoods, where fast food is usually cheaper and more convenient than grocery stores.

“If you look at a map of the U.S. and plot out the neighborhoods where there’s no grocery store within a mile and there’s a high percentage of people who have no car, those are the areas where there’s the highest rates of obesity,” she said.

There’s also the time factor, she said: “Can you afford to cook your own meals, or do you have to work two jobs?”

An unusual experiment by the Department of Housing and Urban Development demonstrated the degree to which physical surroundings can influence obesity risk, Pereira said. In the 1990s, hundreds of mothers who were living in public housing were offered housing vouchers they could use only in wealthier neighborhoods. Ten to 15 years later, the women randomly assigned to receive the windfall had significantly lower rates of severe obesity (14.4%) than women in a control group who weren’t offered vouchers (17.7%). They were also less likely to have a body mass index of 35 or higher (31.1% vs. 35.5%).

Two women talk in New York.

(Mark Lennihan / Associated Press)

The American Medical Assn. recognized obesity as a disease in 2013. People with the chronic condition are at heightened risk of cardiovascular disease, Type 2 diabetes, 13 types of cancer, osteoarthritis, asthma and other health problems. Researchers have pegged the annual medical costs associated with obesity at $174 billion in the U.S. alone.

Some people with obesity are able to lose weight by changing their diets and burning more calories through exercise. But that doesn’t work for people who have developed resistance to leptin, a hormone that suppresses appetite.

“If you try to lose weight with diet and exercise, your body is going to fight you,” said Dr. Caroline Apovian, co-director of the Center for Weight Management and Wellness at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. “Your leptin levels go down, and when leptin goes down, a signal goes to the brain that you don’t have enough fat to survive.” That prompts the release of another hormone, ghrelin, that triggers feelings of hunger.

Leptin resistance also makes exercise less worthwhile.

“Your body fights you by decreasing your total energy expenditure,” Apovian said. “When your muscles work, they work more efficiently. If you want to lose 10 pounds, you’re going to get really, really hungry. And you can’t fight that. Your body thinks it’s starving to death.”

The “breakthrough” drugs counteract this by impersonating a hormone called glucagon-like peptide 1, or GLP-1, that’s involved in appetite regulation. Inside cells, the drugs bind with the same receptors as GLP-1, reducing blood sugar and slowing digestion. They also last longer than their natural counterparts.

Oprah Winfrey credits the new generation of medications for helping her keep her weight under control.

(Chris Pizzello / Associated Press)

The first so-called GLP-1 receptor agonist was approved in 2005 to treat diabetes, and early versions had to be injected once or twice a day. Ozempic improved on this by requiring an injection only once a week. After clinical trials showed that the drug helped people with obesity achieve substantial, sustainable weight loss, the FDA approved Wegovy as a weight management drug in 2021.

Mounjaro and Zepbound also mimic GLP-1, along with a related hormone called glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide, or GIP.

Linda Morales credits Ozempic and Mounjaro for helping her lose 100 pounds and drop from a size 22 to a size 14. The 25-year-old instructional aide at Lankershim Elementary School in North Hollywood said she started to become overweight in middle school and carried 293 pounds on her 5-foot, 5-inch frame when she was referred to the Center for Weight Management and Metabolic Health at Cedars-Sinai two years ago.

She is no longer breathless when she climbs stairs, has an easier time when she goes bowling and fits comfortably into the seat on the Harry Potter ride at Universal Studios. Thanks to the medications, she is no longer on a path toward Type 2 diabetes.

Her job with the Los Angeles Unified School District comes with health insurance that covers the pricey drugs and charges her a copay of $30 a month for her Mounjaro prescription. She said she could swing a monthly payment of up to $50, but beyond that she’d have to stop taking the drug and hope the lifestyle changes she’d made would be enough to sustain the weight loss she’s achieved so far.

“It would definitely get hard for me, for sure,” Morales said.

Indeed, even when the drugs are covered by insurance or patients qualify for discounts from pharmaceutical companies, researchers have found that they often remain out of reach.

In one study, Eberly and her colleagues examined insurance claims for nearly 40,000 people who received a prescription for GLP-1 copycats. Patients who had to pay at least $50 a month to fill their prescriptions were 53% less likely to get most of their refills over the course of a year compared to patients whose copayments were less than $10. Even patients whose out-of-pocket costs were between $10 and $50 were 38% less likely to buy the medicine regularly for a full year, the team found.

In another study of insured patients with Type 2 diabetes, those who were Black were 19% less likely to be treated with these drugs than those who were white, while Latino patients were 9% less likely to get them, Eberly and her colleagues reported.

In some parts of the country, Black patients with diabetes are only half as likely as white patients to get GLP-1 drugs, according to research by Dr. Serena Jigchuan Guo at the University of Florida, who studies health disparities in pharmaceutical access. The disparity was greatest in places with the highest overall usage of the medications, including New York, Silicon Valley and South Florida.

“In those places, the drug is actually widening the gap,” she said.

Researchers have spent years documenting racial disparities in the use of effective treatments for obesity, such as bariatric surgery. Newer drugs like Ozempic simply bring the problem into sharper focus, said Dr. Hamlet Gasoyan, an investigator with the Cleveland Clinic’s Center for Value-Based Care Research.

“We get excited every time a new, effective treatment becomes available,” Gasoyan said. “But we should be equally concerned that this new and effective treatment reduces disparities between the haves and have-nots.”

Science

Canny as a crocodile but dumber than a baboon — new research ponders T. rex's brain power

In December 2022, Vanderbilt University neuroscientist Suzana Herculano-Houzel published a paper that caused an uproar in the dinosaur world.

After analyzing previous research on fossilized dinosaur brain cavities and the neuron counts of birds and other related living animals, Herculano-Houzel extrapolated that the fearsome Tyrannosaurus rex may have had more than 3 billion neurons — more than a baboon.

As a result, she argued, the predators could have been smart enough to make and use tools and to form social cultures akin to those seen in present-day primates.

The original “Jurassic Park” film spooked audiences by imagining velociraptors smart enough to open doors. Herculano-Houzel’s paper described T. rex as essentially wily enough to sharpen their own shivs. The bold claims made headlines, and almost immediately attracted scrutiny and skepticism from paleontologists.

In a paper published Monday in “The Anatomical Record,” an international team of paleontologists, neuroscientists and behavioral scientists argue that Herculano-Houzel’s assumptions about brain cavity size and corresponding neuron counts were off-base.

True T. rex intelligence, the scientists say, was probably much closer to that of modern-day crocodiles than primates — a perfectly respectable amount of smarts for a therapod to have.

“What needs to be emphasized is that reptiles are certainly not as dim-witted as is commonly believed,” said Kai Caspar, a biologist at Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf and co-author of the paper. “So whereas there is no reason to assume that T. rex had primate-like habits, it was certainly a behaviorally sophisticated animal.”

Brain tissue doesn’t fossilize, and so researchers examine the shape and size of the brain cavity in fossilized dinosaur skulls to deduce what their brains may have been like.

In their analysis, the authors took issue with Herculano-Houzel’s assumption that dinosaur brains filled their skull cavities in a proportion similar to bird brains. Herculano-Houzel’s analysis posited that T. rex brains occupied most of their brain cavity, analogous to that of the modern-day ostrich.

But dinosaur brain cases more closely resemble those of modern-day reptiles like crocodiles, Caspar said. For animals like crocodiles, brain matter occupies only 30% to 50% of the brain cavity. Though brain size isn’t a perfect predictor of neuron numbers, a much smaller organ would have far fewer than the 3 billion neurons Herculano-Houzel projected.

“T. rex does come out as the biggest-brained big dinosaur we studied, and the biggest one not closely related to modern birds, but we couldn’t find the 2 to 3 billion neurons she found, even under our most generous estimates,” said co-author Thomas R. Holtz, Jr., a vertebrate paleontologist at University of Maryland, College Park.

What’s more, the research team argued, neuron counts aren’t an ideal indicator of an animal’s intelligence.

Giraffes have roughly the same number of neurons that crows and baboons have, Holtz pointed out, but they don’t use tools or display complex social behavior in the way those species do.

“Obviously in broad strokes you need more neurons to create more thoughts and memories and to solve problems,” Holtz said, but the sheer number of neurons an animal has can’t tell us how the animal will use them.

“Neuronal counts really are comparable to the storage capacity and active memory on your laptop, but cognition and behavior is more like the operating system,” he said. “Not all animal brains are running the same software.”

Based on CT scan reconstructions, the T. rex brain was probably “ a long tube that has very little in terms of the cortical expansion that you see in a primate or a modern bird,” said paleontologist Luis Chiappe, director of the Dinosaur Institute at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

“The argument that a T. Rex would have been as intelligent as a primate — no. That makes no sense to me,” said Chiappe, who was not involved in the study.

Like many paleontologists, Chiappe and his colleagues at the Dinosaur Institute were skeptical of Herculano-Houzel’s original conclusions. The new paper is more consistent with previous understandings of dinosaur anatomy and intelligence, he said.

“I am delighted to see that my simple study using solid data published by paleontologists opened the way for new studies,” Herculano-Houzel said in an email. “Readers should analyze the evidence and draw their own conclusions. That’s what science is about!”

When thinking about the inner life of T. rex, the most important takeaway is that reptilian intelligence is in fact more sophisticated than our species often assumes, scientists said.

“These animals engage in play, are capable of being trained, and even show excitement when they see their owners,” Holtz said. “What we found doesn’t mean that T. rex was a mindless automaton; but neither was it going to organize a Triceratops rodeo or pass down stories of the duckbill that was THAT BIG but got away.”

Science

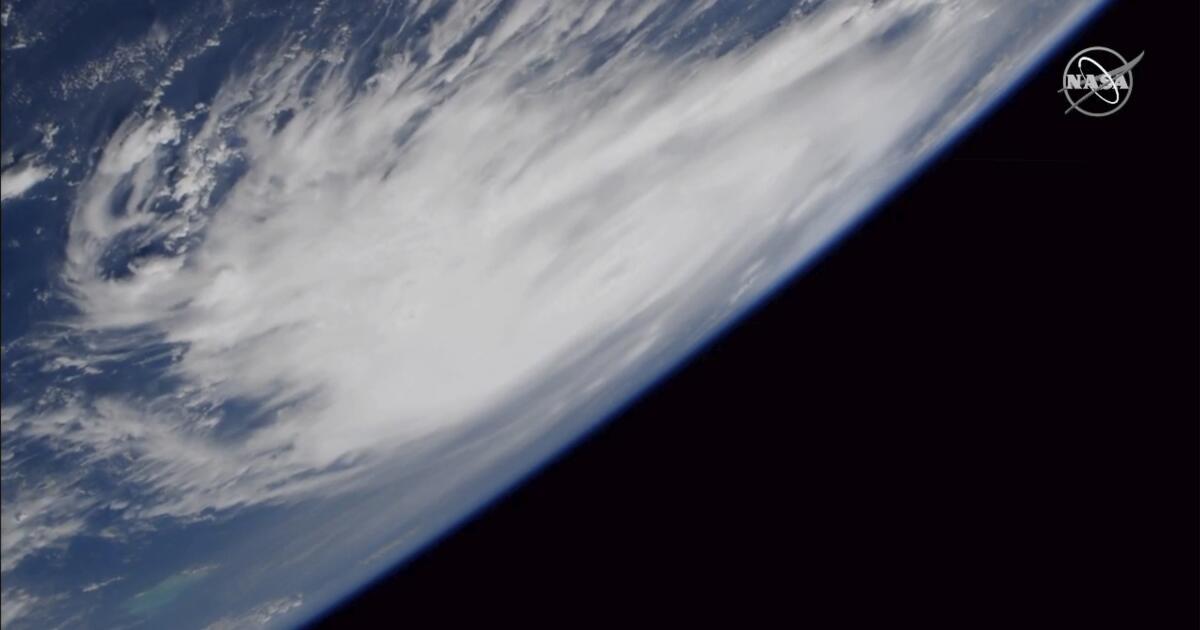

You're gonna need a bigger number: Scientists consider a Category 6 for mega-hurricane era

In 1973, the National Hurricane Center introduced the Saffir-Simpson scale, a five-category rating system that classified hurricanes by wind intensity.

At the bottom of the scale was Category 1, for storms with sustained winds of 74 to 95 mph. At the top was Category 5, for disasters with winds of 157 mph or more.

In the half-century since the scale’s debut, land and ocean temperatures have steadily risen as a result of greenhouse gas emissions. Hurricanes have become more intense, with stronger winds and heavier rainfall.

With catastrophic storms regularly blowing past the 157-mph threshold, some scientists argue, the Saffir-Simpson scale no longer adequately conveys the threat the biggest hurricanes present.

Earlier this year, two climate scientists published a paper that compared historical storm activity to a hypothetical version of the Saffir-Simpson scale that included a Category 6, for storms with sustained winds of 192 mph or more.

Of the 197 hurricanes classified as Category 5 from 1980 to 2021, five fit the description of a hypothetical Category 6 hurricane: Typhoon Haiyan in 2013, Hurricane Patricia in 2015, Typhoon Meranti in 2016, Typhoon Goni in 2020 and Typhoon Surigae in 2021.

Patricia, which made landfall near Jalisco, Mexico, in October 2015, is the most powerful tropical cyclone ever recorded in terms of maximum sustained winds. (While the paper looked at global storms, only storms in the Atlantic Ocean and the northern Pacific Ocean east of the International Date Line are officially ranked on the Saffir-Simpson scale. Other parts of the world use different classification systems.)

Though the storm had weakened to a Category 4 by the time it made landfall, its sustained winds over the Pacific Ocean hit 215 mph.

“That’s kind of incomprehensible,” said Michael F. Wehner, a senior scientist at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and co-author of the Category 6 paper. “That’s faster than a racing car in a straightaway. It’s a new and dangerous world.”

In their paper, which was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Wehner and co-author James P. Kossin of the University of Wisconsin–Madison did not explicitly call for the adoption of a Category 6, primarily because the scale is quickly being supplanted by other measurement tools that more accurately gauge the hazard of a specific storm.

“The Saffir-Simpson scale is not all that good for warning the public of the impending danger of a storm,” Wehner said.

The category scale measures only sustained wind speeds, which is just one of the threats a major storm presents. Of the 455 direct fatalities in the U.S. due to hurricanes from 2013 to 2023 — a figure that excludes deaths from 2017’s Hurricane Maria — less than 15% were caused by wind, National Hurricane Center director Mike Brennan said during a recent public meeting. The rest were caused by storm surges, flooding and rip tides.

The Saffir-Simpson scale is a relic of an earlier age in forecasting, Brennan said.

“Thirty years ago, that’s basically all we could tell you about a hurricane, is how strong it was right now. We couldn’t really tell you much about where it was going to go, or how strong it was going to be, or what the hazards were going to look like,” Brennan said during the meeting, which was organized by the American Meteorological Society. “We can tell people a lot more than that now.”

He confirmed the National Hurricane Center has no plans to introduce a Category 6, primarily because it is already trying “to not emphasize the scale very much,” Brennan said. Other meteorologists said that’s the right call.

“I don’t see the value in it at this time,” said Mark Bourassa, a meteorologist at Florida State University’s Center for Ocean-Atmospheric Prediction Studies. “There are other issues that could be better addressed, like the spatial extent of the storm and storm surge, that would convey more useful information [and] help with emergency management as well as individual people’s decisions.”

Simplistic as they are, Herbert Saffir and Robert Simpson’s categories are the first thing many people think of when they try to grasp the scale of a storm. In that sense, the scale’s persistence over the years helps people understand how much the climate has changed since its introduction.

“What the Saffir-Simpson scale is good for is quantifying, showing, that the most intense storms are becoming more intense because of climate change,” Wehner said. “It’s not like it used to be.”

Science

Opinion: America's 'big glass' dominance hangs on the fate of two powerful new telescopes

More than 100 years ago, astronomer George Ellery Hale brought our two Pasadena institutions together to build what was then the largest optical telescope in the world. The Mt. Wilson Observatory changed the conception of humankind’s place in the universe and revealed the mysteries of the heavens to generations of citizens and scientists alike. Ever since then, the United States has been at the forefront of “big glass.”

In fact, our institutions, Carnegie Science and Caltech, still help run some of the largest telescopes for visible-light astronomy ever built.

But that legacy is being threatened as the National Science Foundation, the federal agency that supports basic research in the U.S., considers whether to fund two giant telescope projects. What’s at stake is falling behind in astronomy and cosmology, potentially for half a century, and surrendering the scientific and technological agenda to Europe and China.

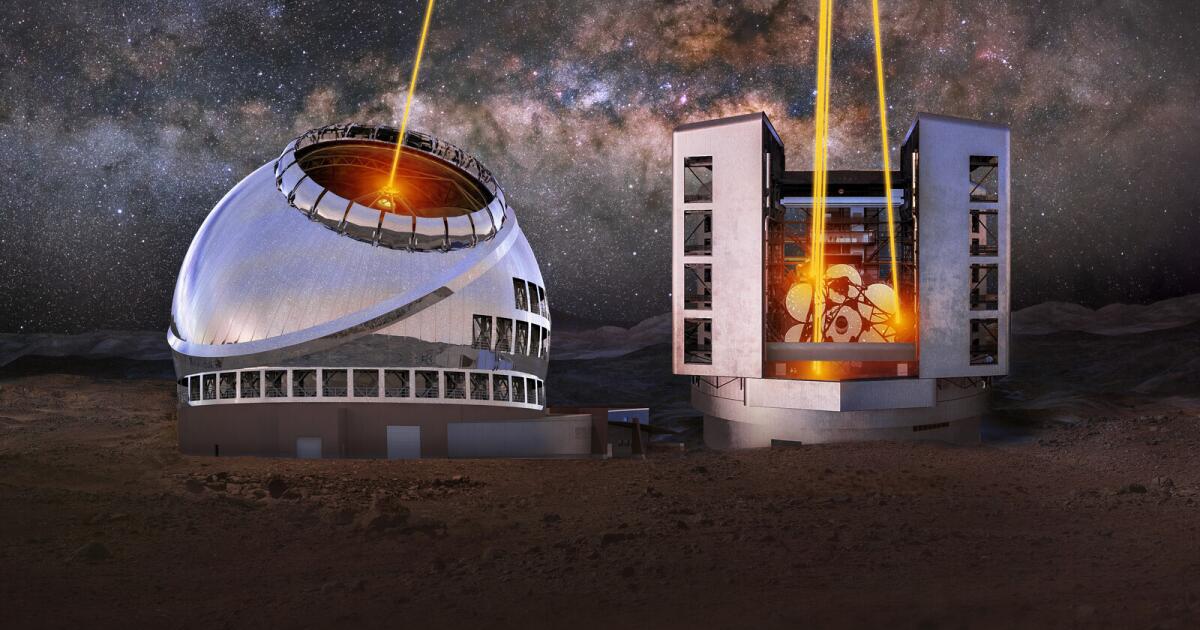

In 2021, the National Academy of Sciences released Astro2020. This report, a road map of national priorities, recommended funding the $2.5-billion Giant Magellan Telescope at the peak of Cerro Las Campanas in Chile and the $3.9-billion Thirty Meter Telescope at Mauna Kea in Hawaii. According to those plans, the telescopes would be up and running sometime in the 2030s.

NASA and the Department of Energy backed the plan. Still, the National Science Foundation’s governing board on Feb. 27 said it should limit its contribution to $1.6 billion, enough to move ahead with just one telescope. The NSF intends to present their process for making a final decision in early May, when it will also ask for an update on nongovernmental funding for the two telescopes. The ultimate arbiter is Congress, which sets the agency’s budget.

America has learned the hard way that falling behind in science and technology can be costly. Beginning in the 1970s, the U.S. ceded its powerful manufacturing base, once the nation’s pride, to Asia. Fast forward to 2022, the U.S. government marshaled a genuine effort toward rebuilding and restarting its factories — for advanced manufacturing, clean energy and more — with the Inflation Reduction Act, which is expected to cost more than $1 trillion.

President Biden also signed into law the $280-billion CHIPS and Science Act two years ago to revive domestic research and manufacturing of semiconductors — which the U.S. used to dominate — and narrow the gap with China.

As of 2024, America is the unquestioned leader in astronomy, building powerful telescopes and making significant discoveries. A failure to step up now would cede our dominance in ways that would be difficult to remedy.

The National Science Foundation’s decision will be highly consequential. Europe, which is on the cusp of overtaking the U.S. in astronomy, is building the aptly named Extremely Large Telescope, and the United States hasn’t been invited to partner in the project. Russia aims to create a new space station and link up with China to build an automated nuclear reactor on the moon.

Although we welcome any sizable grant for new telescope projects, it’s crucial to understand that allocating funds sufficient for just one of the two planned telescopes won’t suffice. The Giant Magellan and the Thirty Meter telescopes are designed to work together to create capabilities far greater than the sum of their parts. They are complementary ground stations. The GMT would have an expansive view of the southern hemisphere heavens, and the TMT would do the same for the northern hemisphere.

The goal is “all-sky” observation, a wide-angle view into deep space. Europe’s Extremely Large Telescope won’t have that capability. Besides boosting America’s competitive edge in astronomy, the powerful dual telescopes, with full coverage of both hemispheres, would allow researchers to gain a better understanding of phenomena that come and go quickly, such as colliding black holes and the massive stellar explosions known as supernovas. They would put us on a path to explore Earth-like planets orbiting other suns and address the question: “Are we alone?”

Funding both the GMT and TMT is an investment in basic science research, the kind of fundamental work that typically has led to economic growth and innovation in our uniquely American ecosystem of scientists, investors and entrepreneurs.

Elon Musk’s SpaceX is the most recent example, but the synergy goes back decades. Basic science at the vaunted Bell Labs, in part supported by taxpayer contributions, was responsible for the transistor, the discovery of cosmic microwave background and establishing the basis of modern quantum computing. The internet, in large part, started as a military communications project during the Cold War.

Beyond its economic ripple effect, basic research in space and about the cosmos has played an outsized role in the imagination of Americans. In the 1960s, Dutch-born American astronomer Maarten Schmidt was the first scientist to identify a quasar, a star-like object that emits radio waves, a discovery that supported a new understanding of the creation of the universe: the Big Bang. The first picture of a black hole, seen with the Event Horizon Telescope, was front-page news in 2019.

We understand that competing in astronomy has only gotten more expensive, and there’s a need to concentrate on a limited number of critical projects. But what could get lost in the shuffle are the kind of ambitious projects that have made America the scientific envy of the world, inspiring new generations of researchers and attracting the best minds in math and science to our colleges and universities.

Do we really want to pay that price?

Eric D. Isaacs is the president of Carnegie Science, prime backer of the Giant Magellan Telescope. Thomas F. Rosenbaum is president of Caltech, key developer of the Thirty Meter Telescope.

-

Kentucky1 week ago

Kentucky1 week agoKentucky first lady visits Fort Knox schools in honor of Month of the Military Child

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoIs this fictitious civil war closer to reality than we think? : Consider This from NPR

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoShipping firms plead for UN help amid escalating Middle East conflict

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoICE chief says this foreign adversary isn’t taking back its illegal immigrants

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week ago'Nothing more backwards' than US funding Ukraine border security but not our own, conservatives say

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoThe San Francisco Zoo will receive a pair of pandas from China

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoTwo Mexican mayoral contenders found dead on same day

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoRepublican aims to break decades long Senate election losing streak in this blue state