Science

James Reason, Who Used Swiss Cheese to Explain Human Error, Dies at 86

The story of how James Reason became an authority on the psychology of human error begins with a teapot.

It was the early 1970s. He was a professor at the University of Leicester, in England, studying motion sickness, a process that involved spinning his subjects round and round, and occasionally revealing what they had eaten for breakfast.

One afternoon, as he was boiling water in his kitchen to make tea, his cat, a brown Burmese named Rusky, sauntered in meowing for food. “I opened a tin of cat food,” he later recalled, “dug in a spoon and dolloped a large spoonful of cat food into the teapot.”

After swearing at Rusky, Professor Reason berated himself: How could he have done something so stupid?

The question seemed more intellectually engaging than making people dizzy, so he ditched motion sickness to study why humans make mistakes, particularly in high-risk settings.

By analyzing hundreds of accidents in aviation, railway travel, medicine and nuclear power, Professor Reason concluded that human errors were usually the byproduct of circumstances — in his case, the cat food was stored near the tea leaves, and the cat had walked in just as he was boiling water — rather than being caused by careless or malicious behavior.

That was how he arrived at his Swiss cheese model of failure, a metaphor for analyzing and preventing accidents that envisions situations in which multiple vulnerabilities in safety measures — the holes in the cheese — align to create a recipe for tragedy.

“Some scholars play a critical role in founding a whole field of study: Sigmund Freud, in psychology. Noam Chomsky, in linguistics. Albert Einstein, in modern physics,” Robert L. Sumwalt, the former chairman of National Transportation Safety Board, wrote in a 2018 blog post. “In the field of safety, Dr. James Reason has played such a role.”

Professor Reason died on Feb. 4 in Slough, a town about 20 miles west of London. He was 86.

His death, in a hospital, was caused by pneumonia, his family said.

A gifted storyteller, Professor Reason found vivid and witty ways to explain complicated ideas. At conferences, on TV news programs and in consultation with government safety officials around the world, he would sometimes deploy slices of cheese as props.

In one instructional video, he sat at his dining room table, which was set for a romantic dinner, with a bottle of wine, two glasses and a cutting board layered with cheese.

“In an ideal world, each defense would look like this,” he said, holding up a slice of cheese without holes. “It would be solid and intact.”

Then he reached for another slice, one with quarter-size cutouts. “But in reality, each defense is like this,” he said. “It has holes in it.”

The metaphor was easy to understand.

“All defenses have holes in them,” Professor Reason continued. “Every now and again, the holes line up so that there can be some trajectory of accident opportunity.”

To explain how the holes develop, he put them in two categories: active failures, or mistakes typically made by people who, for example, grab the cat food instead of the tea leaves; and latent conditions, or mistakes made in construction, written instructions or system design, like storing two scoopable substances near each other in a cabinet.

“Nearly all organizational accidents involve a complex interaction between these two sets of factors,” he wrote in his autobiography, “A Life in Error: From Little Slips to Big Disasters” (2013).

In the Chernobyl nuclear accident, he identified latent conditions that had been in existence for years: a poorly designed reactor; organizational mismanagement; and inadequate training procedures and supervision for frontline operators, who triggered the catastrophic explosion by making the error of turning off several safety systems at once.

“Rather than being the main instigators of an accident, operators tend to be the inheritors of system defects,” he wrote in “Human Error” (1990). “Their part is that of adding the final garnish to a lethal brew whose ingredients have already been long in the cooking.”

Professor Reason’s model has been widely used in health care.

“When I was in medical school, an error meant you screwed up, and you should just try harder to not screw up,” Robert Wachter, the chairman of the department of medicine at the University of California San Francisco, said in an interview. “And if it was really bad, you would probably get sued.”

In 1998, a doctor he had recently hired for a fellowship said he wanted to specialize in patient-safety strategy, to which Dr. Wachter replied, “What’s that?” There were no formal systems or methods in his hospital (or most others) to analyze and prevent errors, but there was plenty of blame to go around, most of it aimed at doctors and nurses.

This particular doctor had trained at Harvard Medical School, where they were incorporating Professor Reason’s ideas into patient-safety programs. Dr. Wachter, who began reading Professor Reason’s journal articles and books, said the Swiss cheese model was “an epiphany,” almost “like putting on a new pair of glasses.”

Someone given the wrong dose of medicine, he realized, could have been the victim of poor syringe design rather than a careless nurse. Another patient could have died of cardiac arrest because a defibrillator that was usually stored in the hallway had been taken to a different floor to replace one that had malfunctioned — and there was no system to alert anyone that it had been moved.

“When an error happens, our instinct can’t be to look at this at the final stage,” Dr. Wachter said, “but to look at the entirety of the system.”

When you do, he added, you realize that “these layers of protection are pretty porous in ways that you just didn’t understand until we opened our eyes to all of it.”

James Tootle was born on May 1, 1938, in Garston, a village in Hertfordshire, northwest of London. His father, Stanley Tootle, died in 1940, during World War II, when he was struck by shrapnel while playing cards in the bay window of his house. His mother, Hilda (Reason) Tootle, died when he was a teenager.

His grandfather, Thomas Augustus Reason, raised James, who took his surname.

In 1962, he graduated from the University of Manchester with a degree in psychology. He received his doctorate in 1967 from the University of Leicester, where he taught and conducted research before joining the faculty at the University of Manchester in 1977.

He married Rea Jaari, an educational psychologist, in 1964. She survives him, along with their daughters, Paula Reason and Helen Moss, and three grandchildren.

Throughout his career, Professor Reason’s surname was a reliable source of levity.

“The word ‘reason’ is, of course, widely used in the English language, but it does not describe what Jim is rightly famous for, namely ‘error,’” Erik Hollnagel, the founding editor of the International Journal of Cognition, Technology and Work, wrote in the preface to Professor Reason’s autobiography. “Indeed, ‘error’ is almost the opposite of ‘reason.’”

Still, it made sense.

“Jim has certainly brought reason to the study of error,” he wrote.

Science

How a Supreme Court win for public health bolstered RFK Jr. and threatens no-cost vaccines

WASHINGTON — Public health advocates won a big case in the Supreme Court on the last day of this year’s term, but the victory came with an asterisk.

The decision ended one threat to the no-cost preventive services — from cancer and diabetes screenings to statin drugs and vaccines — used by more than 150 million Americans who have health insurance.

But it did so by empowering the nation’s foremost vaccine skeptic: Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

Losing would have been “a terrible result,” said Washington attorney Andrew Pincus. Insurers would have been free to quit paying for the drugs, screenings and other services that were proven effective in saving lives and money.

But winning means that “the secretary has the power to set aside” the recommendations of medical experts and remove approved drugs, he said. “His actions will be subject to review in court,” he added.

The new legal fight has already begun.

Last month, Kennedy cited a “crisis of public trust” when he removed all 17 members of a separate vaccine advisory committee. His replacements included some vaccine skeptics.

The vaccines that are recommended by this committee are included as preventive services that insurers must provide.

On Monday, the American Academy of Pediatrics and other medical groups sued Kennedy for having removed the COVID-19 vaccine as a recommended immunization for pregnant women and healthy children. The suit called this an “arbitrary” and “baseless” decision that violates the Administrative Procedure Act.

“We’re taking legal action because we believe children deserve better,” said Dr. Susan J. Kressly, the academy’s president. “This wasn’t just sidelining science. It’s an attack on the very foundation of how we protect families and children’s health.”

On Wednesday, Kennedy postponed a scheduled meeting of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force that was at the center of the court case.

“Obviously, many screenings that relate to chronic diseases could face changes,” said Richard Hughes IV, a Washington lawyer and law professor. “A major area of concern is coverage of PrEP for HIV,” a preventive drug that was challenged in the Texas lawsuit that came to the Supreme Court.

By one measure, the Supreme Court’s 6-3 decision was a rare win for liberals. The justices overturned a ruling by Texas judges that would have struck down the popular benefit that came with Obamacare. The 2012 law required insurers to provide at no cost the preventive services that were approved as highly effective.

But conservative critics had spotted what they saw was a flaw in the Affordable Care Act. They noted the task force of unpaid medical experts who recommend the best and most cost-effective preventive care was described in the law as “independent.”

That word was enough to drive the five-year legal battle.

Steven Hotze, a Texas employer, had sued in 2020 and said he objected on religious grounds to providing HIV prevention drugs, even if none of his employees were using those drugs.

The suit went before U.S. District Judge Reed O’Connor in Fort Worth, who in 2018 had struck down Obamacare as unconstitutional. In 2022, he ruled for the Texas employer and struck down the required preventive services on the grounds that members of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force made legally binding decisions even though they had not been appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate.

The 5th Circuit Court put his decision on hold but upheld his ruling that the work of the preventive services task force was unconstitutional because its members were “free from any supervision” by the president.

Last year, the Biden administration asked the Supreme Court to hear the case of Xavier Becerra vs. Braidwood Management. The appeal said the Texas ruling “jeopardizes health protections that have been in place for 14 years and millions of Americans currently enjoy.”

The court agreed to hear the case, and by the time of the oral argument in April, the Trump administration had a new secretary of HHS. The case was now Robert F. Kennedy Jr. vs. Braidwood Management.

The court’s six conservatives believe the Constitution gives the president full executive power to control the government and to put his officials in charge. But they split on what that meant in this case.

The Constitution says the president can appoint ambassadors, judges and “all other Officers of the United States” with Senate approval. In addition, “Congress may by law vest the appointment of such inferior officers” in the hands of the president or “the heads of departments.”

Option two made more sense, said Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh. He spoke for the court, including Chief Justice John G. Roberts and Justice Amy Coney Barrett, and the court’s three liberal justices.

“The Executive Branch under both President Trump and President Biden has argued that the Preventive Services Task Force members are inferior officers and therefore may be appointed by the Secretary of HHS. We agree,” he wrote.

This “preserves the chain of political accountability. … The Task Force members are removable at will by the Secretary of HHS, and their recommendations are reviewable by the Secretary before they take effect.”

The ruling was a clear win for Kennedy and the Trump administration. It made clear the medical experts are not “independent” and can be readily replaced by RFK Jr.

It did not win over the three justices on the right. Justice Clarence Thomas wrote a 37-page dissent.

“Under our Constitution, appointment by the President with Senate confirmation is the rule. Appointment by a department head is an exception that Congress must consciously choose to adopt,” he said, joined by Justices Samuel A. Alito and Neil M. Gorsuch.

Science

Life expectancy in California still hasn't rebounded since the pandemic

During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the virus caused life expectancy in California to drop significantly.

It’s now been over two years since officials declared the pandemic-related public health emergency to be over. And yet, life expectancy for Californians has not fully recovered.

Today, however, the virus has been replaced by drug overdoses and cardiovascular disease as the main causes driving down average lifespans.

A new study published in the medical journal JAMA by researchers from UCLA, Northwestern, Princeton and Virginia Commonwealth University finds that the average life expectancy for Californians in 2024 was nearly a year less than in 2019. The shortfall of 0.86 year signals that only about two-thirds of the state’s pandemic-era losses of 2.92 years have been reversed.

Using mortality data from the California Comprehensive Death Files and population estimates from the American Community Survey, the researchers calculated annual life expectancy from 2019 to 2024, breaking the figures down by race, ethnicity, income and cause of death.

Although the COVID-19 virus was the primary factor in life expectancy declines during the pandemic’s peak, accounting for 61.6% of the life expectancy gap, its impact has significantly lessened. In 2024, COVID-19 accounted for only 12.8% of the life expectancy gap compared with 2019, while drug overdoses and cardiovascular disease contributed more — 19.8% and 16.3%, respectively.

For Black and Hispanic Californians, recovery has been even slower. Life expectancy for Black residents in 2024 remained 1.48 years below 2019 levels, while for Hispanic residents it was 1.44 years lower. In contrast, the gap for white residents was 0.63 year, and for Asian residents, who have the highest life expectancy in the state at 85.51 years, it was 1.06 years. Overall, the life expectancy for Black Californians in 2024 was under 73.5 years, more than a dozen years lower than that of Asian Californians.

Janet Currie, a co-author of the study and professor at Princeton University, noted that these disparities are especially striking. “You saw the very big hit that Hispanic people and Black people took during the pandemic,” she said, “but you also see that Black people in particular are still not caught up.” She added that although Hispanic populations saw a faster rebound, they too remain behind.

Income-based disparities in life expectancy persist in stark form. Californians living in the lowest-income census tracts (the bottom quartile) experienced a 0.99-year gap in 2024 compared with 2019, while those in the highest-income quartile had a slightly smaller 0.85-year gap. However, the overall life expectancy difference between these groups, 5.77 years, was nearly identical to the prepandemic gap of 5.63 years, suggesting that income-based health disparities persist even as pandemic impacts recede.

The study highlights drug overdoses as a primary post-pandemic-emergency driver of reduced life expectancy. Black Californians and residents of low-income areas were especially affected. In 2023, drug overdoses contributed nearly a full year (0.99 year) to the life expectancy deficit for Black Californians and over half a year (0.52) for residents of low-income areas.

That said, there are signs that state and national efforts to address the overdose crisis may be yielding early results. The number for Black Californians declined to 0.55 year in 2024 while it declined to 0.26 year for residents in low-income areas; in the same time frame, the statewide number dropped from 0.4 year to 0.17 year.

Currie attributed the initial surge in overdose deaths in part to the pandemic itself; there were disruptions in access to treatment, and many Californians suffered greater isolation. While she welcomed the recent progress, she cautioned that the share of deaths attributable to overdoses remains high and emphasized that this was “one of the real bad consequences of the pandemic.”

Meanwhile, cardiovascular disease is now the leading contributor to life expectancy loss among high-income Californians. In 2024, it accounted for 0.22 year of the gap for the wealthiest quartile, more than COVID-19 did at 0.10 year. The authors note this is consistent with statewide rising rates of obesity, which may be playing a role.

Dr. Tyler Evans, chief medical officer and chief executive of Wellness Equity Alliance as well as the author of the book “Pandemics, Poverty, and Politics: Decoding the Social and Political Drivers of Pandemics from Plague to COVID-19,” emphasized how the pandemic exacerbated long-standing health inequities. “These chronic health inequities were further amplified as the result of the pandemic,” he said. While investments in social determinants of health initially helped mitigate some of the worst outcomes, he added, “the funding dried up,” making recovery harder for communities already at greater risk of poor outcomes.

Evans also pointed to a broader pattern of overlapping health crises that he described as a “syndemic,” a convergence of epidemics such as addiction, chronic disease and poor access to care that interact to worsen outcomes for historically marginalized populations. “Until we invest in that sort of foundation long term, the numbers will continue to decline,” he said. “California should be a leader in health improvement outcomes in the country, not a state that continues to have our survival decline.”

Although the findings are limited to California and based on preliminary 2024 data, the study provides an early glimpse into post-pandemic mortality trends ahead of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s national life expectancy dataset, expected to be published later this year. California, home to one-eighth of the U.S. population, provides valuable insight into how racial, ethnic and socioeconomic disparities continue to shape public health.

Ultimately, the study highlights how although the most visible impacts of COVID-19 may have faded, their ripple effects, compounded by ongoing structural inequities, continue to shape life and death in California. The pandemic may have accelerated long-standing public health challenges, and the recovery, the study makes clear, has been uneven and incomplete.

Currie warned that further cuts to Medicaid and public hospitals could make these gaps even worse. “We know what to do. We just don’t do it,” she said.

Science

Commentary: A candid take on mortality and the power of friendship

They gather several times a week in the parking lot of a Vons supermarket in Mar Vista, and no subject is off-limits. Not even the grim medical prognosis for 70-year-old David Mays, one of the founding members of the coffee klatch.

“It’s one of our major topics of conversation,” said Paul Morgan, 45, a klatch regular.

Mays is a cancer survivor with a full package of maladies, including diabetes, a faltering heart and failing kidneys. But since I met him almost two years ago, he has told me repeatedly that he doesn’t want dialysis treatment, even though it might extend his life.

“I get it, because it’s a lot of hours out of your day,” said Morgan, a schoolteacher who lives nearby. “People think you go in for dialysis for 15 minutes before you go straight to work. But really, it’s a part-time job.”

Steve Lopez

Steve Lopez is a California native who has been a Los Angeles Times columnist since 2001. He has won more than a dozen national journalism awards and is a four-time Pulitzer finalist.

His treatment would require that he visit a dialysis center three times a week, for four hours each time, Mays said.

“For the rest of my life.”

“I don’t think I could do it,” said klatcher Kit Bradley, 70, who lives in a van near the supermarket with his dog, Lea.

I met Mays in October 2023, when he was living in his Chevy Malibu in a downtown garage that was part of the Safe Parking L.A. program. Mays later moved into an apartment in East Hollywood and still lives there, but his health has continued to deteriorate.

“He is Stage 5,” said Dr. Thet Thet Aung, Mays’ nephrologist at Kaiser Permanente West Los Angeles.

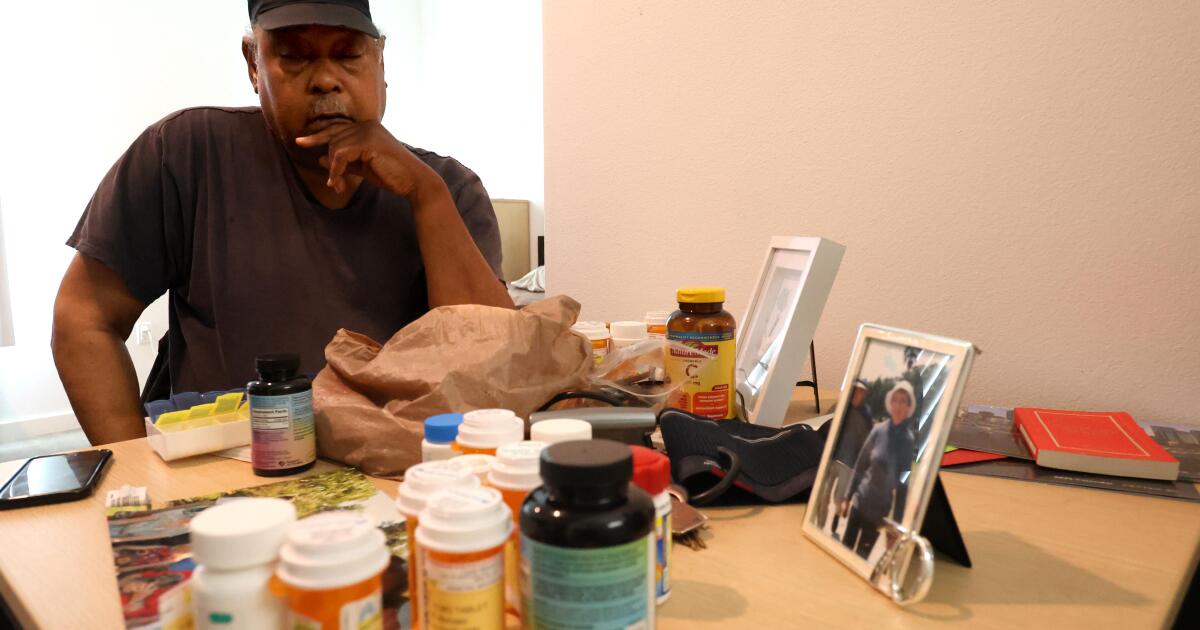

David Mays, center, enjoys a morning get-together with Paul Morgan, left, and Kit Bradley in a Vons parking lot in West Los Angeles on June 25, 2025.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

For such patients, Aung said, death can be imminent. She told me she’s had many conversations with Mays about his treatment options, including dialysis in a clinic or self-administered at home. But not everyone does well on dialysis, she added, and when a patient makes an informed choice, “we respect their wishes.”

Mays has a refreshingly healthy attitude about mortality. Multibillion-dollar industries cater to those who want to look younger and live longer, and about 25% of Medicare’s massive outlay is spent on patients in the last year of life, many of whom choose life-extending medical procedures.

Mays, in the time I’ve known him, has been realistic rather than fatalistic. He has told me he doesn’t think bravery, faith or spirituality has anything to do with his desire to let nature take its course.

“It transcends those things,” he said.

He’s at peace with his fate, he explained, because he’s got friends, love and support.

On a recent day at his apartment, I watched Mays load medication from more than 20 vials into a weekly pill organizer.

“I could almost do this in my sleep,” he said as he arranged meds that resembled miniature jelly beans. This one for his kidneys, that one for his heart, his blood pressure, and on and on.

Bottles of medication and photos of close friends rest on David Mays’ table at his apartment in East Hollywood.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

There were 18 pills in each compartment. And none of that will cure any of what ails him, he said.

“You just have to keep doing it, and doing it, just to stay at a sustained level,” he said. “It’s not like … I feel great because I took this stuff.”

Two women in Mays’ life are heartbroken about his condition but respectful of his refusal to try dialysis.

“I don’t want him to suffer for the sake of placating other people,” said Mays’ daughter Jennifer Nutt, 47, of Merced.

Her parents divorced when she and her brother were young, and Nutt had no relationship with Mays until recently. She’s had her own trials, Nutt said, including homelessness.

Father and daughter began connecting in the fall of 2024.

“We spend hours every day talking. It’s like a nonstop festival of catching up,” and they’ve discovered they have the same cheeky sense of humor and pragmatism, and similar traits and interests.

“We like big words and thick books,” Nutt said.

The other woman is Helena Bake, of Perth, Australia, a registered nurse Mays affectionately refers to as “Precious.” They met in 1985, when Mays was visiting London, and Bake, 18 at the time, was working in a restaurant he visited with friends. After Bake moved to Australia, Mays visited her many times and became close to her entire family.

“He was lovely,” said Bake, who is not surprised by Mays’ attitude about his deteriorating health. “He’s always very positive and so pragmatic. He has this wonderful view of the world and the people in his life. It’s such a gift that he has.”

Mays, who gets by on Social Security payments, has set up a GoFundMe page to help pay for his cremation and send his ashes to Bake, to be scattered in his favorite places in Australia.

Lately, medical appointments with his several doctors, and the occasional ER visit, have gotten in the way of one of Mays’ favorite activities — the gatherings in the Vons parking lot.

David Mays is “always very positive and so pragmatic. He has this wonderful view of the world and the people in his life. It’s such a gift that he has,” a longtime friend says.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

Mays worked for many years in the Mar Vista area as a live-in elder care provider, and he’d bump into Bradley at a park, or Morgan in the strip mall that includes the grocery store. Several years ago, they made a habit of grabbing coffee around 7 a.m. and hanging out near Mays’ car. Bradley’s dog often hops into the vehicle, a Vons employee named Elvis comes out for a smoke break, and others come and go.

“I had a cousin who had diabetes, and he called my mom one day and said, ‘I’m not doing it anymore,’ ” Morgan was saying the other day. His mother wasn’t supportive at first, he told the klatch, but she listened to her nephew’s explanation and came around. “Who could judge someone for the choices they make in that situation?”

“There’s a waiting list for kidneys of two to eight years,” Mays said. “Let’s say [in] four or five years, there was a kidney available. Your body can reject it … and then you’re back to the drawing board…. I told Precious about this like a year and a half ago … and she said, ‘I have to hang up now because I have to process this.’ And the next time I talked with her, she said, ‘I get it.’ ”

Mays said he doesn’t want to be “a prisoner to a process, like a machine or something.”

“And you have to do this indefinitely. It’s not like you’re on it for two or three years…,” he said. “It is. The. Rest. Of. Your. Life.”

“I’ve seen people that were on dialysis,” said Bradley, a former musician. “I think I’d rather be just, if I gotta go, I gotta go.”

Morgan said his father, who died last year, had kidney problems in the end and resisted extreme measures to extend his life.

“It’s not like he was at all suicidal, just like David’s not,” Morgan said. “The thing about David is, he’s always been so resolute about it. We’ve never had a discussion where I felt like we could waver him, or like he was on the fence.”

When he first resisted dialysis, Mays said, doctors set him up in a room with a video that explained the process.

“I watched the whole thing, and that was the clincher,” Mays said. “By the time I got through looking at that, I’m just going, ‘Oh HELL no.’”

It’s not that he wants to die, Mays said. It’s that he wants to live on his terms.

“The irony of the whole thing is, it’s all the people that I have around me — they’re the reason I’m willing to go like this. What I get from them in the way of being … uplifted and loved, well, when you have all that, you can deal with anything.”

He has his klatch buddies, he has Precious, he has his daughter in his life again.

“With people around that give a damn about you, care about you, you can deal … with death, you can deal with dying…. And I told my doctors I would rather live a shorter period of time, but with what I feel to be some decent quality of life, than live a longer period of time and be miserable. And I would be miserable on dialysis,” Mays said.

“Plus, I’m 70. It ain’t like I’m 30 and there’s so much life to live. I am the age that I am, and I would like to go further, sure, but it has to close out soon. And I’m fine with that, because I have lived.”

steve.lopez@latimes.com

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoSee How Trump’s Big Bill Could Affect Your Taxes, Health Care and Other Finances

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week ago16 Mayors on What It’s Like to Run a U.S. City Now Under Trump

-

Politics7 days ago

Politics7 days agoVideo: Trump Signs the ‘One Big Beautiful Bill’ Into Law

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: Who Loses in the Republican Policy Bill?

-

Science1 week ago

Science1 week agoFederal contractors improperly dumped wildfire-related asbestos waste at L.A. area landfills

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoMeet Soham Parekh, the engineer burning through tech by working at three to four startups simultaneously

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoCongressman's last day in office revealed after vote on Trump's 'Big, Beautiful Bill'

-

World7 days ago

World7 days agoRussia-Ukraine war: List of key events, day 1,227