Vermont

Vermont prosecutors rarely have secured hate crime convictions. A recent legislative change might make it easier

The killing of a transgender girl in Morristown final week has spurred calls to cost the alleged assassin with a hate crime. However regulation enforcement officers say for now, they don’t have proof to assist that cost.

Judicial information present that Vermont prosecutors have not often secured hate crime convictions previously 5 years, although a latest legislative change was designed to make it simpler for them to win such instances.

Police say 29-year previous Fern Feather, of Hinesburg, was stabbed to dying by Seth Brunell final Tuesday. Brunell, 43, has pleaded not responsible to second-degree homicide. If convicted, he faces a life sentence. He’s presently being held with out bail at Northeast Correctional Complicated in St. Johnsbury.

Brunell’s lawyer didn’t reply to a request for remark.

Extra from VPR: Pals mourn Fern Feather, lover of crops and birds, after killing in Morristown

Based on court docket information, Feather, who grew up within the Northeast Kingdom city of Albany, picked up Brunell hitchhiking, and the 2 spent a number of days collectively. Round 10:20 a.m. on April 12, Morristown police responded to a name a couple of man standing subsequent to a physique at an intersection on the town. Police discovered Brunell close to Feather’s physique after they arrived. Feather had been stabbed within the chest, police mentioned in an affidavit.

Brunell, based on court docket information, instructed police that Feather attacked him after he rejected a sexual advance. “I used to be simply defending myself,” Brunell allegedly mentioned to the officers.

Police mentioned they didn’t see any indicators that Brunell had been attacked, based on court docket information.

As police proceed to analyze the case, a web based petition asking prosecutors so as to add a hate crimes cost has been signed by 9,117 folks.

“It could be sufficient to indicate that one of many causes that the defendant dedicated the act was due to this particular person’s standing in a kind of protected classes. And that is merely a a lot simpler bar for the prosecution to fulfill.”

Jared Carter, Vermont Legislation College

Kim Jordan, director of the SafeSpace Anti-Violence Program at Satisfaction Middle of Vermont, mentioned Brunell’s justification for the alleged crime facilities round Feather’s identification.

“That claims to me, and I’d say to loads of queer and trans people that, ‘Oh, this can be a hate crime,’” Jordan mentioned.

However regulation enforcement officers aren’t able to convey a hate crime cost — but.

“We’re not going to hurry into something,” mentioned Aliena Gerhard, a deputy state’s lawyer in Lamoille County. “I believe it could be extra devastating to simply add it on as a result of it appears good, and never be capable of show it. Once we prosecute a case, we make it possible for we now have sturdy proof, in order that we will show it past an affordable doubt.”

Extra from VPR: What number of hate crimes occurring in Vermont? FBI statistics do not inform the entire story

Vermont regulation permits prosecutors so as to add a hate crime “enhancement” if the suspect’s actions are motivated by bias in the direction of a protected class, which embody race, gender identification and sexual orientation. The enhancement will increase the legal penalties a suspect faces, relying on the severity of the underlying crime.

However latest historical past suggests it is tough to acquire a conviction for a hate crime in Vermont, even when the info of the case counsel some stage of bias.

State prosecutors filed 66 hate crime fees between 2017 and 2021, based on the Vermont Judiciary. However there have solely been seven hate crime convictions in that point. One stemmed from a St. Albans incident the place, court docket information say, a person threatened and shouted racial slurs at his neighbors, together with the household’s 3-year-old son.

“We’re not going to hurry into something. I believe it could be extra devastating to simply add it on as a result of it appears good, and never be capable of show it. Once we prosecute a case, we make it possible for we now have sturdy proof, in order that we will show it past an affordable doubt.”

Aliena Gerhard, Lamoille County deputy state’s lawyer

Hate crimes have typically confirmed tough to prosecute. In 2018, the state supreme court docket narrowly overturned a disorderly conduct conviction — with a hate crime enhancement — of a person who allegedly put Ku Klux Klan recruitment flyers within the mailboxes of a Black girl and a Mexican girl in Burlington. The court docket wrote that the defendant’s conduct didn’t convey an “imminent risk of hurt.”

“To the extent it conveys a message of non-public risk to the recipient, it’s that the Klan will recruit members and inflict hurt sooner or later,” wrote former affiliate justice John Dooley within the determination.

In different latest instances, hate crime fees have been dropped as a part of plea offers. An Essex man who shouted racial slurs and waved a gun at a comfort retailer clerk pleaded responsible in 2018 to aggravated assault and reckless endangerment, however the disorderly conduct cost with a hate crime enhancement was dropped as a part of the plea deal, the Burlington Free Press reported.

In one other incident, a hate crime cost levied towards a young person accused of spray portray racial epithets on the athletic fields behind South Burlington Excessive College was dropped after he pleaded responsible to lesser fees, based on the Burlington Free Press.

Extra from Vermont Version: A Satisfaction Middle chief on supporting Vermont’s trans neighborhood

There have been efforts to make it simpler to prosecute hate crimes, together with a change to Vermont’s statute. Final yr, lawmakers amended the regulation to categorise hate crimes as actions “motivated in complete or partly” by a “sufferer’s precise or perceived” identification. Beforehand, the statue mentioned the crime wanted to be “maliciously motivated.”

Jared Carter, a professor at Vermont Legislation College, mentioned the brand new regulation makes it simpler for prosecutors to show hate crime allegations.

“It could be sufficient to indicate that one of many causes that the defendant dedicated the act was due to this particular person’s standing in a kind of protected classes,” Carter mentioned. “And that is merely a a lot simpler bar for the prosecution to fulfill.”

One other invoice handed by the Legislature final yr bans defendants from justifying violent actions primarily based on the precise or perceived sexual orientation or gender identification of the sufferer, a change Carter mentioned might be related in Feather’s homicide case.

Brunell, based on court docket information, instructed police his actions had been in self-defense and that he rejected a sexual advance from Feather as a result of he “wasn’t homosexual.”

The U.S Lawyer’s Workplace also can pursue federal hate crime fees in Vermont, which it did for the primary time in 2019. Federal authorities charged Stuart Kurt Rollins, of Barre, with intimidating and harassing his Hispanic neighbors. Rollins pleaded responsible to at least one depend of legal interference with truthful housing rights, a federal hate crime, and was sentenced to time served and three years of supervised launch.

“I do assume it could be useful and useful. However I don’t assume calling it a hate crime will forestall additional hate.”

Kim Jordan, Satisfaction Middle of Vermont

Vermont’s high federal prosecutor, who was appointed in December, has mentioned his workplace plans to deal with bias incidents and hate crimes.

“We’re dedicated to investigating these sorts of conditions which may implicate federal regulation,” U.S. Lawyer Nikolas Kerest instructed Vermont Version in January.

Jordan, with Satisfaction Middle of Vermont, thinks regulation enforcement officers ought to name Feather’s killing a hate crime, partly to make seen “what so many queer and trans folks know.”

“So in that respect, I do assume it could be useful and useful,” Jordan mentioned. “However I don’t assume calling it a hate crime will forestall additional hate.”

Have questions, feedback or ideas? Ship us a message or get in contact with reporter Liam Elder-Connors @lseconnors.

Vermont

Burlington car break-in suspect arrested in Brattleboro

BURLINGTON, Vt. (WCAX) – A Burlington man who police say is connected to a string of car break-ins has been arrested in Brattleboro.

Police say Yesi Garelnabi, 33, is responsible for multiple thefts from cars. He had a warrant for his arrest when police in Brattleboro arrested him. They say he also had stolen credit cards and a stolen backpack.

He was released on conditions but was re-arrested a short time later after being accused of stealing from another car.

Copyright 2024 WCAX. All rights reserved.

Vermont

Vermont’s rate of homelessness now ranks 4th in the nation – VTDigger

This story, by Report for America corps member Carly Berlin, was produced through a partnership between VTDigger and Vermont Public.

As the number of people experiencing homelessness in Vermont continues to rise to record levels, the Green Mountain State’s per-capita rate of homelessness remains among the highest in the nation.

That’s according to a new analysis of the 2024 point-in-time count, a coordinated, federally-mandated tally of unhoused people taken each January. The annual report on the count, which took place nearly a year ago, was released by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development late last week.

The department found that about 53 out of every 10,000 Vermonters were unhoused when the count took place, putting Vermont fourth on the state-by-state list. In 2022 and 2023, it had the second-highest rate in the nation, a distinction that turned heads as Vermont’s homelessness crisis has grown more visible.

But Vermont’s shift in this oft-cited nationwide comparison shouldn’t necessarily be read as an indication of improvement locally, said Anne Sosin, a public health researcher at Dartmouth College who studies homelessness.

“I wouldn’t take it as a hopeful sign that it’s fourth instead of second,” Sosin said.

While Vermont’s homeless population rose 5% last year, to a record 3,458 people in January 2024, other states saw much more dramatic increases.

Catastrophic wildfires in Maui displaced thousands of people from their homes, the HUD report notes, with many sleeping in disaster emergency shelters when the count took place in January. Hawaii saw an 87% rise in homelessness year-over-year, with 81 people per 10,000 residents recorded as unhoused — the highest rate in the nation. New York shared the same rate, which increased this year, in part, due to an influx of asylum seekers to New York City’s shelter system, according to the report.

Across the country, the annual tally registered the highest number of people experiencing homelessness ever recorded since the point-in-time count began in 2007. Over 771,000 people nationwide were unhoused at the time of the count: a 18% rise from the 2023 count.

The “worsening national affordable housing crisis,” inflation, stagnating wages, and “the persisting effects of systemic racism have stretched homelessness services systems to their limits,” the report notes. And the end of pandemic-era supports, like the expanded child tax credit, have also likely contributed to the national rise in homelessness, it says.

The point-in-time count figure is generally considered to be an undercount. HUD does not tally people who are doubling up with relatives or couch-surfing, and people who are unsheltered are often more difficult to find.

Even as the number of people experiencing homelessness has ticked up, the HUD analysis reflects that Vermont has done a better job than most other states at keeping unhoused people indoors. Over 95% of Vermont’s homeless population was in some form of shelter as of January — either a traditional shelter, or a hotel or motel covered by an emergency housing voucher. Only neighboring New York had a higher rate of people in shelter, according to the report.

Still, the January tally recorded a jump in the number of people living unsheltered in Vermont from a year earlier. And observers expect the 2025 count, which will take place in a few weeks, will capture an even larger number of people sleeping outdoors or in their vehicles.

That’s because over 1,500 people were pushed out of the state’s motel voucher program this fall, after a series of cost-cutting measures went into effect. The program’s rules have since loosened for the winter, allowing some people to re-enter, though cold-weather access is more limited now than in previous years and both shelter space and motel rooms are scarce.

Already this winter, Burlington officials have observed more people living outside than this time last year, said Sarah Russell, the city’s special assistant to end homelessness. When the city opened an extreme cold-weather shelter for the weekend before Christmas — in part because the opening of its regular seasonal shelter has been delayed until the new year — “the number of folks that we saw there was huge,” Russell said. About 50 people showed up the first night, and 80 the next.

“It’s just too cold for people to be living outside,” Russell said.

The HUD report does show signs of progress. Nationally, homelessness among veterans dropped 8% last year — to the lowest number on record, according to a HUD press release. That success can be chalked up to specific housing programs targeted at veterans, the report says, and is often lauded by homelessness advocates as a model for how to tackle homelessness among other groups.

“When there are more resources that are poured into, you know, housing supports for specific sub-populations of folks — the result of that is that it actually drives the numbers down,” Russell said.

The press release also notes several places that saw decreases in homelessness over the past year. Dallas saw its homelessness numbers drop after launching a new program to connect unsheltered people to long-term housing while closing encampments. Chester County, Penn., has seen a nearly 60% drop in homelessness since 2019, after putting in place eviction prevention programs, expanding “housing first” training initiatives, increasing affordable housing groups, and providing fair housing education for migrant workers, according to the release.

When Vermont lawmakers kick off the 2025 legislative session next week, they will get their next chance to tackle the state’s homelessness problem. Their return comes after several deaths of people living outside that have captured the public’s attention in recent weeks.

“My question to Vermont legislators is: how are we going to keep the population experiencing homelessness alive while we make progress on solving homelessness as a state?” said Sosin, the Dartmouth researcher.

Vermont

Increasing pharmacy closures mean long drives for Vermont residents, mirroring a national trend – VTDigger

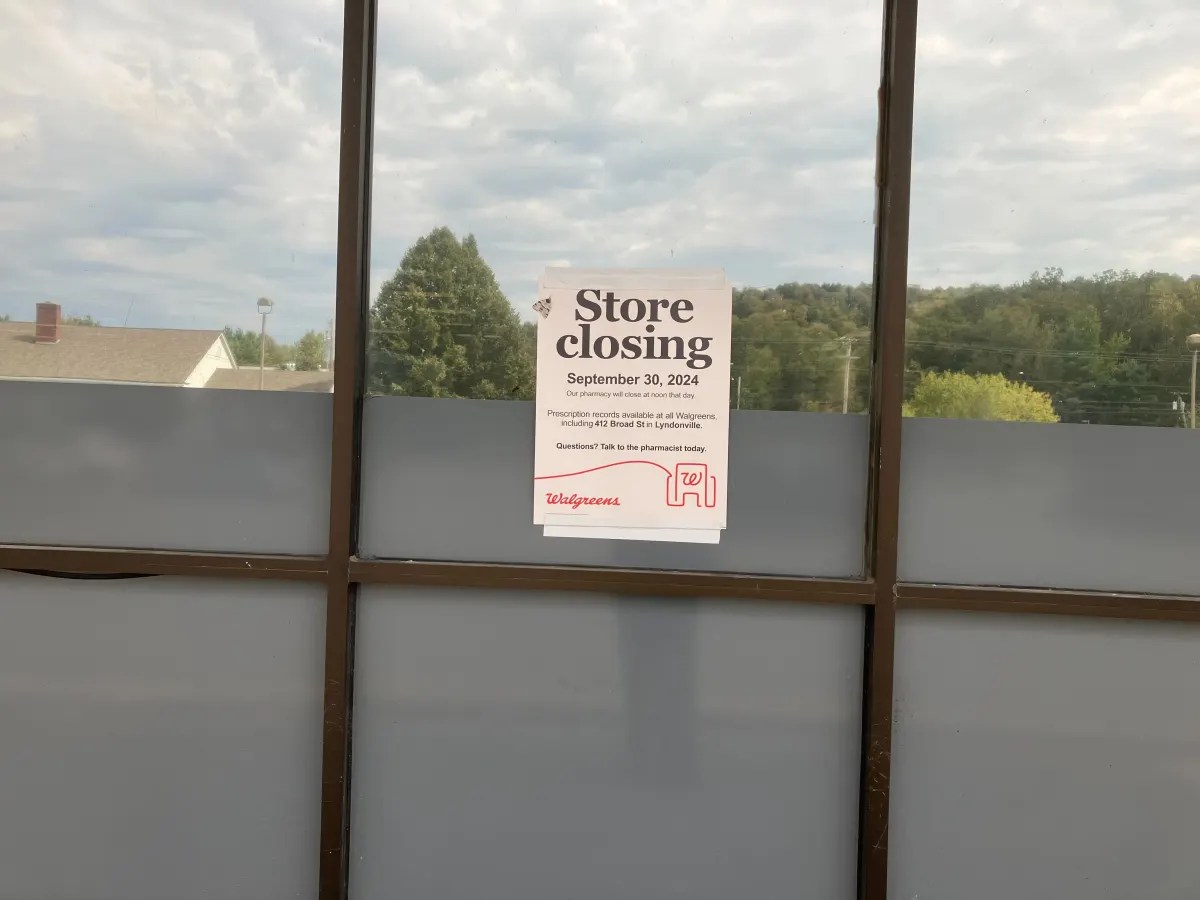

Hardwick’s sole pharmacy — a Walgreens that had twice been hit by Vermont’s recent summer floods — closed for good at the end of September. Since then, residents have had to drive 25 minutes to access a pharmacy in Morrisville or 40 minutes to the closest Walgreens in Lyndon, leaving Hardwick squarely in a “pharmacy desert.”

Pharmacy deserts are generally defined as places where there is no or limited access to a pharmacy. In rural areas, this means the closest is over 10 miles away, while in urban areas, the closest is over one mile away.

Hardwick is hardly the only pharmacy desert in the state. According to a recent analysis of pharmacy locations across the country, 41 of Vermont’s 193 census tracts (21%) had low access to a pharmacy in 2022. The analysis, published by the academic journal Health Affairs Scholar, defined low access as at least one-third of the tract’s population living within a pharmacy desert. Between closures of independent pharmacies and national chains continuing to scale back back “less profitable” operations, the number of pharmacy deserts is only increasing.

Mike Fisher, Vermont’s chief health care advocate, said that pharmacy closures across the state are an ongoing and “very serious” trend.

“I live in Addison County,” he said. “When the local Marble Works Pharmacy closed, I remember just how upsetting and difficult that was for so many people.”

According to the state’s Board of Pharmacy, 28 Vermont pharmacies have closed permanently over the past five years, leaving 126 currently operating in the state. A nationwide study has linked such closures to a decline in older Americans taking their prescription cardiovascular medications.

Often, Fisher said, there’s another pharmacy in town, as in Middlebury. But in a growing number of towns, there isn’t.

According to a study published this month in the journal Health Affairs, more pharmacies closed than opened between 2018 and 2021 both nationally and in Vermont, with independent pharmacies and those located in Black and Latinx communities a higher risk for closure.

Options for those living in a pharmacy desert do exist. In Hardwick, area residents can utilize mail-order pharmacies for their prescriptions and Kinney Drugs offers weekly deliveries. However, Fisher notes, pharmacies don’t solely dispense medications, but also vaccines and advice.

“The pharmacist at the local pharmacy counter is an accessible, front-line healthcare professional that many people depend on,” he said. “You lose something really important when you lose your community pharmacist.”

Marty Irons, a full-time Vermont pharmacist for almost two decades and a member of the Vermont Pharmacists Association’s board, said in an email that the organization is very aware of pharmacy closures and expects them to continue to impact Vermont.

Pharmacists largely attribute closures to pharmacy benefit managers: companies that act as intermediaries between drug manufacturers and insurance companies. In Vermont, two pharmacy benefit managers — CVS Caremark and Express Scripts — account for 95% of Vermont’s drug market for commercial health insurance plans, according to the state Attorney General’s Office.

Pharmacy benefit managers, often abbreviated as PBMs, are known to under-reimburse pharmacies for the costs of filling prescriptions. According to Irons, this loss of income often requires pharmacies to pull back on services — such as the number of hours they’re open — and, in some cases, close.

“Negative, or below cost, reimbursement is no longer the exception,” Mike Duteau, president of the Vermont Association of Chain Drug Stores, said in an email. “The growing impact is so substantial that pharmacies are closing in larger numbers and more quickly.”

READ MORE

In addition, Irons and Duteau point to staffing challenges only exacerbated by the closure of Vermont’s only pharmacy school three years ago.

The Legislature passed a bill this year to regulate PBMs, the system for which is currently being set up at the Department of Financial Regulation, Fisher said. The bill requires PBMs to obtain a license from the department, strengthens its oversight and bans some of the companies’ practices.

In addition, Vermont Attorney General Charity Clark announced a lawsuit against PBMs earlier this year, alleging that the state’s two major PBMs skim money from drug transactions. However, it is unclear how — and how soon — these two state efforts might improve the situation for pharmacies and their customers.

“Our Vermont pharmacy infrastructure is so fragile,” said Irons. “Most people assume it will always be there; I hope so!”

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25672934/Metaphor_Key_Art_Horizontal.png)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25672934/Metaphor_Key_Art_Horizontal.png) Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoThere’s a reason Metaphor: ReFantanzio’s battle music sounds as cool as it does

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoFrance’s new premier selects Eric Lombard as finance minister

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoOn a quest for global domination, Chinese EV makers are upending Thailand's auto industry

-

Health3 days ago

Health3 days agoNew Year life lessons from country star: 'Never forget where you came from'

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24982514/Quest_3_dock.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24982514/Quest_3_dock.jpg) Technology3 days ago

Technology3 days agoMeta’s ‘software update issue’ has been breaking Quest headsets for weeks

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoPassenger plane crashes in Kazakhstan: Emergencies ministry

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoIt's official: Biden signs new law, designates bald eagle as 'national bird'

-

Politics5 days ago

Politics5 days ago'Politics is bad for business.' Why Disney's Bob Iger is trying to avoid hot buttons

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25810760/1374361318.jpg)