Northeast

Baseball player who died in New York plane crash with family hit a grand slam in his final game, coach says

One of the five Georgia family members who died last weekend in a small plane crash in upstate New York hit a grand slam during the last baseball game he played in while visiting Cooperstown, his coach has revealed.

Frank Tumminia Jr., identified by the Times Union newspaper as the coach of 12-year-old James “JR” VanEpps, wrote in a Facebook post that “his parents were too modest and humble to post about his athletic dominance so that is my job today as coach.”

“In his last game in Cooperstown NY, where youth athletes’ dreams are made with storybook backgrounds and brackets full of several dozen teams… JR Van Epps crushed a GRAND SLAM,” Tumminia said.

“Today and for as long as I live I will teach the living testimony of JR. A piece of me left with him… I will remember him as the ultimate human,” he added.

FAMILY WHO DIED IN NEW YORK PLANE CRASH WAS FLYING THROUGH AREA OF ‘STORM ACTIVITY,’ NTSB REVEALS

James VanEpps, 12, Laura VanEpps, 43, Ryan VanEpps, 42, and Harrison VanEpps, 10, were killed in a plane crash in New York Sunday, authorities said. (Courtesy)

A National Transportation Safety Board spokesperson revealed to Fox News Digital on Tuesday that the plane that VanEpps was traveling in passed through an area of “storm activity” on Sunday afternoon before crashing.

The spokesperson said flight tracking data for the single-engine Piper PA-46 aircraft “was lost about 12 minutes after departure” from Alfred S. Nader Regional Airport in Oneonta.

“Preliminary information indicates that the plane was flying from Oneonta, New York to Charleston, West Virginia when it crashed under unknown circumstances,” the NTSB spokesperson added. “Meteorological data shows storm activity along the flight path.”

FAMILY DIES IN NEW YORK PLANE CRASH FOLLOWING COOPERSTOWN BASEBALL TOURNAMENT: POLICE

A Piper PA-46-310P plane, similar to the one involved in the crash in New York on Sunday, June 30. (aviation-images.com/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

New York State Police on Monday identified the five victims in the crash as James VanEpps, Harrison VanEpps, 10, Ryan VanEpps, 42, Laura VanEpps, 43, and Roger Beggs, 76.

“All of the passengers are family members from the state of Georgia and were in Cooperstown, NY for a baseball tournament,” police said, noting that the plane went down in the town of Masonville as it was heading back to Atlanta, with a stopover in West Virginia.

A single-engine Piper PA-46 crashed near Sidney, New York, on Sunday afternoon. Authorities are seen responding to the crash site. (WICZ)

The NTSB said Tuesday that the debris path from the wreckage is about a mile long and that “all major portions of the plane” have been found except for the rudder.

Read the full article from Here

Northeast

Pilot, passenger swim to safety after plane crashes into New York’s Hudson River

NEWYou can now listen to Fox News articles!

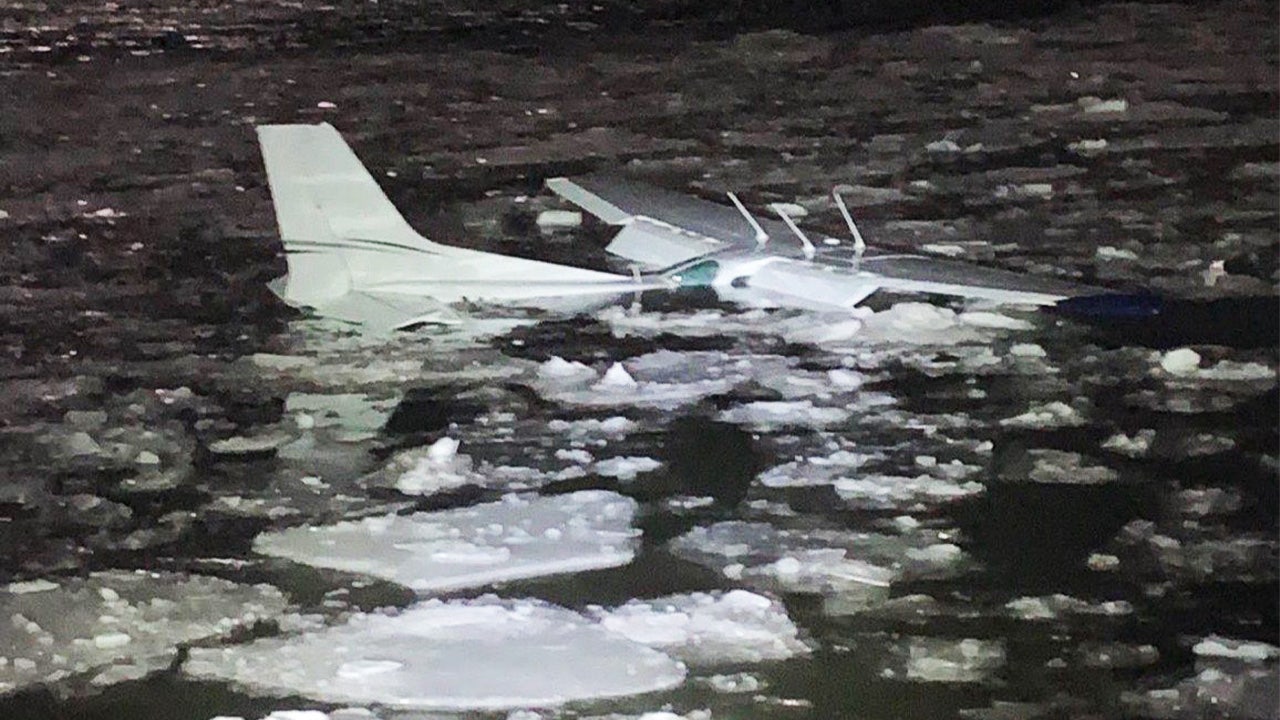

A pilot and passenger swam through the frigid waters of the Hudson River and reached shore safely after their Cessna 172 made an emergency landing Monday night, officials said.

The aircraft had taken off from Long Island when the pilot was forced to land in the river just after 8 p.m., the Middle Hope Fire Department said in a Facebook post.

The Federal Aviation Administration is investigating the incident.

Middle Hope Fire Department responders, along with personnel from other agencies, were dispatched to the scene. After a brief search, first responders located the plane within the City of Newburgh, authorities said.

A plane wades in the Hudson River. (Facebook/Middle Hope Fire Department)

Fire officials said the two occupants were able to free themselves from the aircraft and swim to shore. Newburgh Emergency Medical Services evaluated the pair before they were transported to a nearby hospital for further treatment.

Multiple agencies were on the scene after a plane crashed into the Hudson River. (Facebook/Middle Hope Fire Department)

New York Gov. Kathy Hochul hailed the incident as “Another miracle on Hudson.”

“Thank God both the pilot and passenger of a single engine plane that performed an ice landing near Newburgh have been located with only minor injuries,” the governor wrote in a post on X. “Grateful to our first responders for their quick actions.”

A plane made an emergency landing on the Hudson River Monday evening. (Facebook/Middle Hope Fire Department)

New York Rep. Pat Ryan said he was “closely monitoring reports of a small plane making an emergency landing near the Newburgh-Beacon Bridge.”

“I’m in touch with officials on the ground, who have shared that both passengers are safely out of the water & have been evacuated by EMS,” he said. “Incredibly grateful for our Hudson Valley first responders who are responding swiftly and put their lives on the line to keep others safe.”

First responders found the plane within the city limits of Newburgh. (Facebook/Middle Hope Fire Department)

The cause of the emergency landing remains under investigation.

Read the full article from Here

Boston, MA

Boston honors first casualty of American Revolution – The Boston Globe

“In moments of challenge and in moments of conflict, it does feel easier to put your head down,” Wu said at an event at the Old State House commemorating Attucks.

“Remembering the full history pushes us to be the beacon of freedom that the rest of the country and the rest of the world so very much needs.”

Inside the Old State House’s council chambers, city leaders, historians, and students gathered to celebrate Attucks’ legacy. They talked about the importance of memorializing him during a time when many present said the contributions of people of color to American history were being erased by the Trump administration, and the country’s founding principles were under attack.

Senator Lydia Edwards said the death of Attucks and the four others killed during the Boston Massacre helped establish important legal principles that still guide the country today.

Following the killings, British soldiers involved in the incident were put on trial. John Adams, who later became president, agreed to defend them in court, arguing that the rule of law must be upheld even during times of intense conflict.

“Even in these moments of strife, oppression of rogue federal government, that we remember that we stood up and still held to our court system, to the rule of law and to due process,” Edwards said. “We also remember who had to die in order to remind ourselves to do that.”

City Councilor Brian Worrell said Attucks was a symbol of the long struggle for equality in the country.

“It’s a story that is a reminder that Black and Indigenous Americans have always been at the forefront [of] the fight for justice,” Worrell said.

He said when he recounts Boston’s Black history, he almost always starts with Attucks’ story.

“He fought not simply against the tea tax or the Stamp Act, he fought for the most basic of rights. He fought for equal human lives. It’s a fight we as a city are still having,” he said.

Wu spoke about how on March 5, 2025, she was called to testify before Congress about Boston’s immigration policies during a six-hour hearing. She touted Boston’s safety record amid aggressive questioning, arguing that the city’s immigration policies improved public safety.

“On the 255th anniversary of the Boston Massacre, on Crispus Attucks Day, there was no way that this city wasn’t going to be represented in standing up for what’s right,” Wu said.

A chandelier lit the council chamber and red curtains covered its historic windows. On both sides of the room, students sat with their teachers. Winners of the Crispus Attucks Essay Contest, which invites local students to explore Attucks’ legacy, sat next to the podium.

“Sometimes history repeats itself,” said Toni Martin, an attendee at the event, who came to support her niece, who was being awarded. “Sometimes it gets better, but it takes revolutionary people to make change perfect.”

Outside of the State House after the commemoration, Sharahn Pullum, 18, who came in second for the essay contest, said, “My inspiration was just getting the opportunity to speak on something that matters.”

Michael Kelly, 65, joined the wreath-laying ceremony that took place at the Boston Massacre Commemorative Plaza. Kelly held a sign that said, “Ice Out Be Goode,” referring to Renee Good, a US citizen who was shot and killed by immigration agents in Minneapolis earlier this year.

Kelly said he had been standing at the plaza for three hours and is planning to stand there the entire day.

“People can stretch their imaginations to understand that this place, what happened here, is not at all different than what happened in Minneapolis,” Kelly said with tears in his eyes. “People standing up for something they believe in is vastly important, and we can’t be daunted.”

Aayushi Datta can be reached at aayushi.datta@globe.com.

Pittsburg, PA

Pirates Winning Streak Ends With Loss to Cardinals

PITTSBURGH — The Pittsburgh Pirates have had a strong showing so far in the Grapefruit League, but suffered a surprising defeat.

The Pirates lost 3-2 to the St. Louis Cardinals at LECOM Park in Bradenton, Fla., taking just their third defeat in Spring Training so far, dropping to 9-3 in the Grapefruit League.

Pittsburgh saw their five-game winning streak come to an end, but they are still level with the New York Yankees at the top of the Grapefruit League standings.

This game also came after the first off day for the Pirates on March 4 and a 7-1 win over Team Colombia in an exhibition at LECOM Park on March 3.

How the Pirates Fell to the Cardinals

Pirates right-handed pitcher Mitch Keller made his third start in the Grapefruit League and threw three scoreless innings, before giving up a solo home run to Cardinals third baseman Nolan Gorman on a slider down in the zone, putting the road team up 1-0 in the top of the fourth inning.

That represented the first run that Keller gave up all Spring Training and Pirates left-handed relief pitcher Derek Diamond came in for him after he gave up a single to Cardinals right fielder Jordan Walker.

Keller has just a 1.23 ERA over 7.1 innings for the Pirates in the Grapefruit League, a good start for the veteran on the starting rotation.

St. Louis loaded the bases against Pirates left-handed relief pitcher Evan Sisk in the top of the fifth inning with three walks, but Sisk struckout top prospect in shortstop JJ Wetherholt and forced Gorman into a double play to keep it a one-run game.

Pirates right-handed relief pitcher Chris Devenski gave up a run in the top of the sixth inning, as he walked second baseman Ramón Urías, who stole second base, then gave up a single to catcher Pedro Pagés, doubling the Cardinals’ lead at 2-0.

The Pirates tied the game up at 2-2 in the bottom of the sixth inning, as shortstop Alika Williams hit a two-run home run off of Cardinals left-handed pitcher Quinn Mathews.

Pirates right-handed relief pitcher Cam Sanders gave up the go-ahead run in the top of the eighth inning, hitting leadoff batter Joshua Baez with a pitch and then giving up a single to pinch-hitter Jimmy Crooks to make it 3-2.

Right fielder Ryan O’Hearn had a strong showing for the Pirates in the loss to the Cardinals with two hits in two at-bats. He is now slashing .462/.563/.769 for an OPS of 1.332 in six Grapefruit League games.

Outfielder Jhostynxon Garcia had a hit off the bench for the Pirates, as he is now slashing .533/.611/.733 for an OPS of 1.344 in seven games.

Make sure to visit Pirates OnSI for the latest news, updates, interviews and insight on the Pittsburgh Pirates!

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Wisconsin4 days ago

Wisconsin4 days agoSetting sail on iceboats across a frozen lake in Wisconsin

-

Massachusetts1 week ago

Massachusetts1 week agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Maryland5 days ago

Maryland5 days agoAM showers Sunday in Maryland

-

Massachusetts3 days ago

Massachusetts3 days agoMassachusetts man awaits word from family in Iran after attacks

-

Florida5 days ago

Florida5 days agoFlorida man rescued after being stuck in shoulder-deep mud for days

-

Denver, CO1 week ago

Denver, CO1 week ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Oregon6 days ago

Oregon6 days ago2026 OSAA Oregon Wrestling State Championship Results And Brackets – FloWrestling