Lifestyle

Why Patricia Highsmith's most famous creature, Tom Ripley, continues to fascinate

Andrew Scott plays Tom Ripley in the new Netflix series, Ripley, drawn from Patricia Highsmith’s novel.

Lorenzo Sisti/Netflix © 2021

hide caption

toggle caption

Lorenzo Sisti/Netflix © 2021

Andrew Scott plays Tom Ripley in the new Netflix series, Ripley, drawn from Patricia Highsmith’s novel.

Lorenzo Sisti/Netflix © 2021

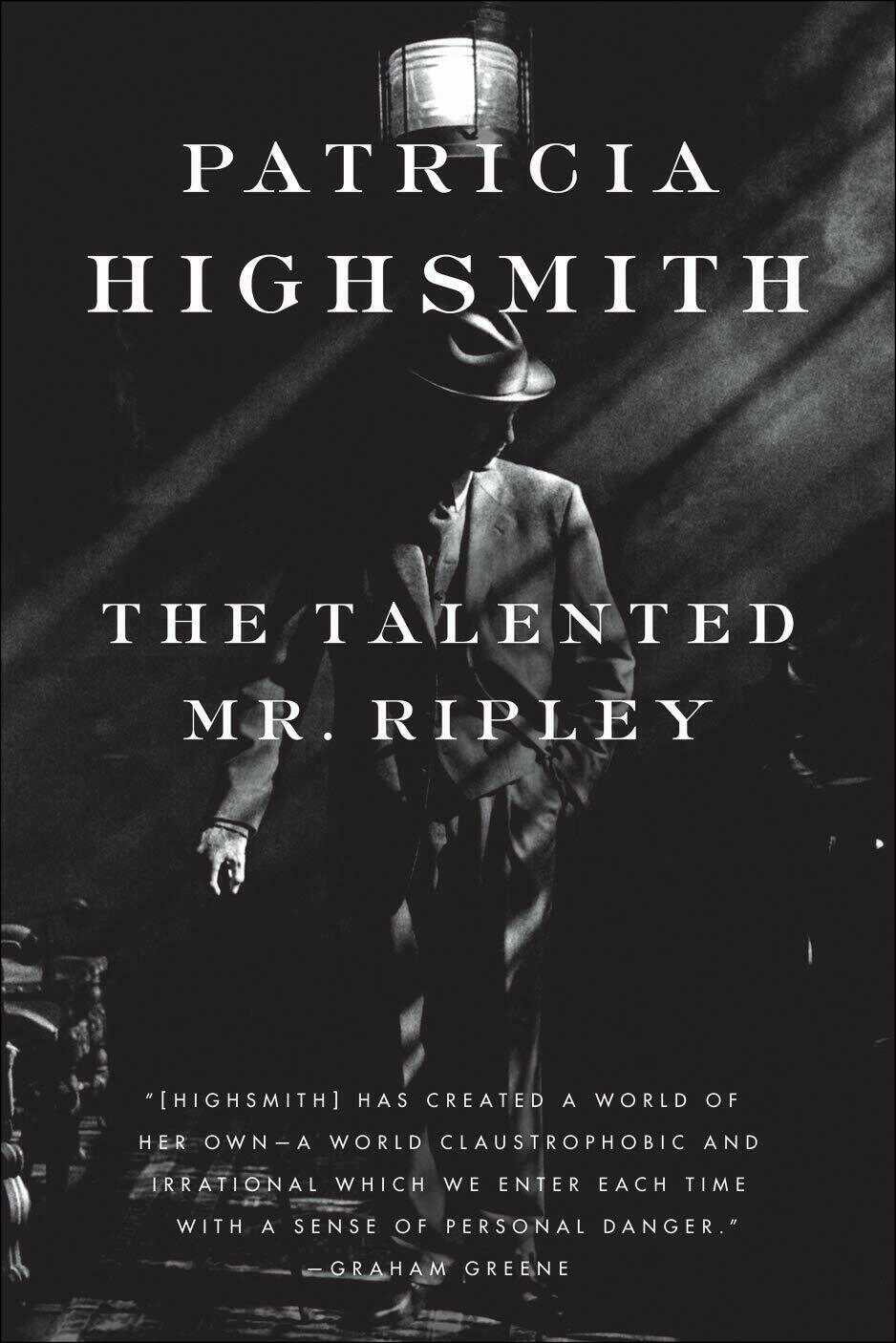

For a total psychopath, Tom Ripley is remarkably popular. As we near the 25th anniversary of the acclaimed Oscar-nominated big screen adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s most infamous creation, The Talented Mr. Ripley, Netflix has released a striking new reimagining, simply titled Ripley. Sinister and visually stunning, the series reminds us why the book continues to influence popular culture.

Through seven decades, Highsmith’s novel, The Talented Mr. Ripley has grown in allure as a masterwork of American noir, boosted by – but distinct from – its adaptations. The core story is always the same: A wealthy man enlists fraudster Tom Ripley, his son’s distant acquaintance, to travel to Italy and woo his errant, playboy son back to the fold; but rather than returning Dickie to his family, an envious Tom disposes of him and assumes his identity. Other murders follow to cover the first.

This bloody-minded serial killer fantasist and antisocial social climber would become Patricia Highsmith’s best known and best loved creation. She published five Ripley novels in all from 1955 to 1991, the last a few years before her death. Since his debut, her all-American psychopath has inspired six screen adaptations, a play by Phyllis Nagy, and a musical staging. That legacy is a testament to Ripley’s complicated appeal – amoral, unassuming and audacious — and Highsmith’s scalpel-sharp writing. There’s something irresistible about an unapologetic grifter, who seizes the chance at a better life by stealing someone else’s. The text is rich enough to handle wildly different interpretations that feel true to the original and brilliant in their own right.

A window into Ripley’s roots

In the first Ripley novel, one childhood scene is especially vivid. When he was 12, and his parents long dead, Tom’s reluctant guardian Aunt Dottie made him get out of her car and run an errand on foot while stuck in traffic. When the cars started moving again, Tom was forced into “running between huge, inching cars, always about to touch the door of Aunt Dottie’s car and never being quite able to…” Instead of waiting, his aunt “had kept inching along as fast as she could go…” Worse, she taunted him, “yelling, ‘Come on, come on, slowpoke!’ out the window.” The memory ends with Tom in teary frustration and his aunt hurling a slur at him: “Sissy! He’s a sissy from the ground up. Just like his father!”

This story bubbles up into the memory of the adult con man Tom Ripley while he’s lying on a ship deck chair on the way to Europe. Buoyed in body and spirit by the luxury and abundance of his surroundings, Tom starts to plot a brighter future for himself. But he keeps returning to past indignities, and that cruel vignette stands out. Looking back from his comfortable perch, Ripley thinks, “It was a wonder he had emerged from such treatment as well as he had.” This isn’t justification, just a part of Ripley’s essence – Ripley as a vulnerable boy rather than cipher or leech or thief, a man whose emotional and physical deprivations curdle into resentment and violence.

Andrew Scott as Tom Ripley in the Netflix series Ripley.

Philippe Antonello/Netflix © 2023

hide caption

toggle caption

Philippe Antonello/Netflix © 2023

That window into Ripley’s roots is one reason I loved re-reading the novel in the lead up to a new adaptation. Highsmith illuminates the inner life of what she recognized as her “psychopath hero” with identification rather than judgment (Highsmith was openly enamored of her creation). That intense interiority is one reason Highsmith is often credited with helping reinvent and popularize the psychological thriller, a genre with roots in the 19th century, and why her influence persists despite a deservedly controversial reputation. Her debut novel became Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train (1951) less than a year after publication, and her 1957 novel Deep Water appears on The Atlantic’s list of 100 Great American novels.

With Ripley, the narration lives outside of Tom but close enough for dissection. We learn that he’s a loner but not completely, that he gets antsy around people, only able to sustain a performance of normalcy for so long. He’s caught between a need for independence born of his smothering yet loveless upbringing and an aching desire for other people’s good regard.

In proximity to beauty and privilege but not of it, Tom’s neediness escalates. He’s ruthless and amoral, but human and self-conscious. He sobs! And he yearns.. Scene by masterful scene, sentence by sentence, with each disturbing thought and memory, Highsmith reveals how Ripley’s psyche veers out of bounds, a slow drip punctuated by shocking jumps. When Dickie and Tom give a taxi home to a local girl they bump into, and she thanks them, calling them the nicest Americans she’s ever met, Tom remarks to Dickie, “You know what most crummy Americans would do in a case like that—rape her.” It’s a sharp kick in the midst of banality.

Worse, when real violent thoughts finally result in action, Tom revels like a pig in mud in his stolen persona. Feeling “blameless and free,” he likens his confidence in Dickie’s shoes to how “a fine actor probably feels when he plays an important role on a stage with the conviction that the role he is playing could not be played better by anyone else.” The great beauty of Highsmith’s novel lies in moments like this, illuminating the dark recesses of a psyche spinning out of control.

A story ripe for retelling

A portrait this faceted begs for retelling and reinvention — it’s a dream role for an actor — but the text also defies total capture. Highsmith could make a two-act play out of the domestic symbolism and social psychological dynamics of Dickie purchasing a refrigerator.

The beauty of the 1999 movie and 2024 series interpretations of Ripley, despite this high bar, is that they’re fully formed artworks of their own.

Gwyneth Paltrow and Jude Law in the film The Talented Mr. Ripley.

Pictorial Press Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

hide caption

toggle caption

Pictorial Press Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

Netflix’s series has both the text and the sublimely entertaining 1999 movie with its constellation of Hollywood stars to live up to. Matt Damon and Jude Law were at the height of their powers as Tom Ripley and Dickie Greenleaf (Law earned a best supporting actor Oscar nomination), and Gwyneth Paltrow was incandescent and multidimensional as Dickie’s girlfriend Marge. They’re memorably supported by Cate Blanchette and Philip Seymour Hoffman as trust fund-babies abroad. Their production is gorgeously shot in the sun-drenched Amalfi coast and the Oscar nominated soundtrack beautifully amplifies the emotion and story. In Anthony Minghella’s screenplay, when the nastiness and violence emerge from Dickie as well as Tom it’s an arresting aberration against this deliberately effervescent, candy-colored backdrop.

The appeal of Minghella’s acclaimed and popular film has more than endured, but it’s not the only classic iteration of Ripley’s debut. The first significant big screen rendering was the 1960 French thriller Purple Noon, starring Alain Delon as a Ripley with beauty that rivals Dickie’s. There are three less celebrated adaptations of other Ripley novels. 2023’s Saltburn wasn’t a Ripley reimagining but its story of upper class ruin at the hands of an interloper seem to spring from a similar well. Plus, the film’s most audacious interlude reads as an homage to Jude Law and Matt Damon’s homoerotic bathtub scene, and the movie and discourse around added new heat to the Highsmith mystique.

Anthony Minghella, far left, director of the film “The Talented Mr. Ripley,” poses with cast members, from left, Matt Damon, Jude Law, Gwyneth Paltrow, Cate Blanchett and Philip Seymour Hoffman at the premiere of the film on Dec. 12, 1999, in the Westwood section of Los Angeles.

Chris Pizzello/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Chris Pizzello/AP

Anthony Minghella, far left, director of the film “The Talented Mr. Ripley,” poses with cast members, from left, Matt Damon, Jude Law, Gwyneth Paltrow, Cate Blanchett and Philip Seymour Hoffman at the premiere of the film on Dec. 12, 1999, in the Westwood section of Los Angeles.

Chris Pizzello/AP

Despite all that history, the pedigreed new Netflix production successfully forges its own haunting vision of Ripley. Written and directed by Steve Zaillian (screenwriter of Schindler’s List and The Irishman), Ripley (mostly) benefits from having more space to breathe than the film – and from Andrew Scott’s unflinching performance.

Leaving the Hot Priest of Fleabag fame behind, Scott gives a harder, colder interpretation of the title role. Though significantly older than Highsmith’s 25-year-old antihero, the 47-year-old BAFTA winner Scott (All of Us Strangers, Sherlock) fully embodies the brooding and seething Ripley. Rather than charming and boyish, Netflix’s Tom Ripley is visibly creased and battered. Instead of Highsmith’s peevish 25-year-old, who notices with pleasure and opportunism physical resemblances with his privileged friend, Ripley and Dickie’s relationship is more clearly grifter and target. Ripley director Zaillan also advances the timeline to 1961, plunging Ripley into a more modern and edgy world.

Scott is well supported by Johnny Flynn (Emma) as a feckless Dickie, and Dakota Fanning, who delivers a mannered and pricklier Marge, the role that Gwyneth Paltrow made famous. If there’s one flaw, it’s that Ripley masters the style and techniques of Hitchcockian noir, without its momentum. This series’ slow deliberate pace and eerie quiet can sometimes feel like a slog.

Still, Ripley‘s performances and striking style elevate the series. Rendered in stark Black and white tones, each shot is as visually arresting as the best still photo. Anthropological and artistic, it’s the opposite of Anthony Minghella’s bright Italian playground presided over by Jude Law as a golden god. This approach transforms even the most ordinary scene —a cat on a bench in a Roman rooming house — into a foreboding tableau. The noirish visuals are the perfect look for this seedier and more cerebral thriller. So too are the peeling paint, decaying edifices, and too many steps on which the camera lingers. All together, the aesthetic looks like something out of an avant-garde European movie like Jean Cocteau’s La Belle et La Bête or a painting by Caravaggio. The series significantly expands on what Highsmith wrote about Tom’s relationship with high art, spinning the idea that he had “discovered an interest in paintings” from emulating Dickie into an obsessive identification with a 17th-century Italian painter known for his bloody and brutal canvases, interplay of shadow and light, and for murder. It’s an ingenious representation of Tom’s descent on screen.

With these inspired creative choices, the Anthony Minghella film and the Netflix series stand on their own. But if you have the inclination, the two major screen productions and the novel form a phenomenal triple bill.

A slow runner and fast reader, Carole V. Bell is a cultural critic and communication scholar focusing on media, politics and identity. You can find her on Twitter @BellCV.

Lifestyle

As National Poetry Month comes to a close, 2 new retrospectives to savor

W. W. Norton & Company, Alice James Books

W. W. Norton & Company, Alice James Books

With National Poetry Month comes spring flowers and some of the year’s biggest poetry publications. And as April wraps up, we wanted to bring you two of our favorites — retrospective collections from two of the best poets of the late 20th and early 21st centuries: Marie Howe and Jean Valentine.

Howe’s New and Selected Poems makes a concise case for Howe’s status as an essential poet. The New & Collected Poems of Jean Valentine gathers all of the beloved late poet’s work, a monument to a treasured career.

New and Selected Poems by Marie Howe

Marie Howe is writing some of the most devastating and devastatingly true poems of her career — and some of the best being written by anyone. Her subject matter, from a bird’s eye, is simply the big questions and their non-answers: What are we here for? What does it mean to do good? What have we done to the environment? What are the consequences and what do we who are here now owe to those who will follow us? And yet her tone and straightforward delivery make her poems as approachable as friends. Howe is the rare poet whose poems one wants to hug closely for company, companionship, and empathy; and yet they are works of literature of the highest order, layered, full of booby traps and shoots and ladders that suddenly transport one between the words. It’s tough love that these poems offer, but it’s undeniably love.

This first retrospective gathers a book’s worth of new poems along with ample selections from of Howe’s four previous collections, each of which was a landmark when it was published. Her nearest antecedent might be Elizabeth Bishop, who also didn’t write very much, or didn’t publish very much, but everything she wrote was good if not capitol-G-Great. Howe is best know for What the Living Do (1997), which remains one of the great books on youth and grief, regret, and moving forward if not moving on. It regards a world in which “anything I’ve ever tried to keep by force I lost.” Startling, almost koan-like statements like this erupt out of unassuming domestic scenes, making everyday life into high drama.

The typical speaker of a Howe poem is a woman who seems much like Marie Howe, even when she is speaking through the voice of the biblical Mary, as she does in Magdalene (2017): “I was driven toward desire by desire.” She is serious except when she’s funny, though she’s rarely laugh out loud funny — it’s more of a kind of internal laughter, either like blossoming light or paper rustling in one’s chest. She is consoling, except when she is taking herself and readers to task, bowing under the simple, Herculean responsibilities that come with living a life, being a parent. She’s tough, sometimes even stoic, except that in almost every poem there is a moment of surprise, a revelation, a piercing insight that injects a kind of pure ecstasy.

Some of the new poems are among the best Howe has written, making them among the best period. Set “In the middle of my life — just past the middle,” these poems grieve lost friends; reckon with the sudden adulthood of a daughter; lament the destruction of the environment; and take the moral measure of this very disturbing era. Each of these everyday dramas becomes an access point for the deepest kind of human reconciliation, where we must finally admit where language fails us. These poems also feature a recurring character, “our little dog Jack,” who, with all best intentions, becomes one of Howe’s most devastating metaphors. But all metaphors have their root in plain fact. As Howe writes in “Reincarnation,” one of her best poems, “Jack may be actually himself — a dog.”

Light Me Down: The New and Collected Poems of Jean Valentine

This is one of those monumental events in American poetry: the life’s work of a major poet gathered in one big book, an opportunity to revel in all that Jean Valentine accomplished in her long and prolific career. As a young poet, Valentine (1934-2020) won the Yale Series of Younger Poets prize in 1965, for her debut collection, Dream Barker. In 2004, she won the National Book Award for Door in the Mountain: New and Collected Poems 1965-2003. In between, and after, she was always well regarded by the mainstream poetry establishment, winning most of the prizes available to an American poet.

But Valentine’s real influence was as a friendly ambassador to and from the avant-garde. It’s hard to pin Valentine’s poems down: I wouldn’t call them experimental, but they are anything but straightforward in their slippages of thought and wide leaps of association. Fairly early in her career, Valentine begin working in a style that had her teasing the reader with images, gently suggesting the way the poem should go, until, perhaps, a thunderclap at the end disturbs the calm. She always knows where to end. Pick almost any poem and the last couple of lines will shock you with their unlikely inevitability.

Valentine writes about everything — love, death, sex, the roiling political situations of the last half-century — with simultaneous candor and mystery: “I have been so far, so deep, so cold, so much,” she says prophetically in an early poem. She asserts that poetry can be made almost entirely through suggestion, that the poet must trust the secret links between one word and another, and trust that the reader will be willing to travel with the poet along those underground currents. In a short poem, a haiku from 1992, “To the Memory of David Kalstone,” dedicated to the literary critic who died in 1986, Valentine offers as succinct a statement of her poetics as one could want: “Here’s the letter I wrote,/ and the ghost letter, underneath—/ that’s my life’s work.” Valentine’s poems draw our attention to the words beneath the words, what’s said between them, in all the white space surrounding the poems.

Elsewhere Valentine opts for simple observations, stirred by a bit of mystery, as in the brief elegy “Rodney Dying (3)”:

“I vacuumed your bedroom

one gray sock

got sucked up it was gone

sock you wore on your warm foot,

walked places in, turned,

walked back

too off your heavy shoes and socks

and swam”

There are no sudden bolts of profundity here, nothing, really, that you could call insight, at least not overtly. Instead, Valentine asks an object, the sock, to carry the grief. This is a technique poets call the “objective correlative” — it’s an image that stands in for an emotion or knot of emotions. That unassuming object, or really just the word for it — sock — becomes a vessel, a kind of canopic jar to contain grief, but also to let it rattle around a bit. The poem ends with what might be an allegory for death, but is also a celebration of Rodney’s vitality. The language is as plain as can be, and yet I exit the poem with uncertainty, equally hopeful and despairing. Valentine is an expert at tensing these sorts of contradictions against one another. The emotional climate in Valentine’s poems is ambivalent in the best way, lit by contradictory energies.

And while this book is a monumental celebration of an extraordinary legacy, it is also sad to hold: Valentine was in an inexhaustible and generous force in American poetry until so recently. It feels impossible to accept the fact that she is dead while reading poems that are so profoundly alive.

Craig Morgan Teicher is the author of several books, including The Trembling Answers, which won the 2018 Lenore Marshall Poetry Prize from the Academy of American Poets, and the essay collection We Begin in Gladness: How Poets Progress.

Lifestyle

Mike Myers Debuts White Hair in First Public Appearance in Over a Year

Mike Myers returned to the spotlight for a rare public appearance this weekend … but folks had to do a double take, ’cause nobody could recognize him with his new hair color.

The actor stepped out Saturday for the 49th AFI Life Achievement Award Gala in L.A. — where Nicole Kidman was being honored — which marked his first time at a public event in about a year.

Mike looked unrecognizable with short white hair — but was rocking it proudly as he spoke onstage at one point … and posing for tons of pics before heading inside, all smiles.

He was even taking photos with fans too … acting goofy and posing for a bunch of selfies.

Mike has always kept a relatively low profile … as he and his wife, Kelly Tisdale, are known for keeping their home life super private. So, seeing MM out and about like this is pretty remarkable — especially since he’s a silver fox now, and totally leaning into it.

The last few times Mike was out in public was in April and May of 2023 — in April of that year, his was quite a bit longer … and more importantly, it was the same color of brown we’ve seen him in for years now.

In May, the guy was at a basketball game — with pretty damn good seats, it seems — but there … he was wearing a beanie, covering up his ‘do. Since then, he’s been kinda MIA.

Anyway, it was clearly a big enough occasion to get Mike out of the house and into the public eye again — remember, this was all about Nicole … and anyone who’s anyone showed up to give her her flowers, including a ton of celebs.

Among the stars in attendance … Reese Witherspoon, Joey King, Michelle Pfeiffer, Jane Seymour, Miles Teller, Naomi Watts, Morgan Freeman and lots of others.

Mike certainly stood out though … and we gotta say, he’s looking real sharp these days!

Lifestyle

In 'Dead Boy Detectives,' two best mates reject their deadly fates : Pop Culture Happy Hour

-

Kentucky1 week ago

Kentucky1 week agoKentucky first lady visits Fort Knox schools in honor of Month of the Military Child

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoIs this fictitious civil war closer to reality than we think? : Consider This from NPR

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoShipping firms plead for UN help amid escalating Middle East conflict

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoICE chief says this foreign adversary isn’t taking back its illegal immigrants

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week ago'Nothing more backwards' than US funding Ukraine border security but not our own, conservatives say

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoThe San Francisco Zoo will receive a pair of pandas from China

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoTwo Mexican mayoral contenders found dead on same day

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoRepublican aims to break decades long Senate election losing streak in this blue state