Lifestyle

Cheryl Burke Says Breadwinner Status Hurt Matthew Lawrence Marriage

Amy and T.J. Podcast

Cheryl Burke‘s proving mo’ money really does mean mo’ problems — at least from her POV … which she says caused a lot of problems in her marriage to Matthew Lawrence.

The “Dancing with the Stars” alum talked about bringing in the big bucks on Amy Robach and T.J. Holmes‘ podcast this week … and, while she says it made her feel good to be the breadwinner between her and Matt, she admits it didn’t do their relationship any favors.

As CB explains it, she never tried to “buy” her ex-husband — but she definitely says she supported the family financially, which she says stoked some tension between the pair.

Burke says she’s fine being self-sufficient — adding she doesn’t really want anyone to take care of her, but does note she’s looking for a partner to grow and evolve with … which, from the sounds of it, she doesn’t think ML was doing while they were still hitched.

She rattles off a long list of attributes she wants in a future partner … and, even though she never says it point blank, ya know she’s got people wondering if she’s saying Matt didn’t meet all these criteria.

Waiting for your permission to load the Instagram Media.

Remember … Cheryl filed for divorce from Matthew Lawrence back in 2022 after being married for a few years — and the split’s been acrimonious, to say the least, with the exes even fighting over custody of their dog Ysabella at one point.

Matthew’s since moved on … striking up a super-serious relationship with TLC singer Chilli — one where they’ve already spoken publicly about marriage and children.

Sounds like Burke’s ready to move on too … however, it also seems she’s got no issue bringing the past in the same breath. BTW, on this same pod … she says leaving ‘DWTS’ was way harder than leaving Matthew.

Waiting for your permission to load the Instagram Media.

Ouch.

Lifestyle

Harvey Weinstein's New York trial, round two, is likely to move forward in the fall

Harvey Weinstein appears in at Manhattan Criminal Court on Wednesday, May 1.

Steven Hirsch/AFP via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Steven Hirsch/AFP via Getty Images

Harvey Weinstein appears in at Manhattan Criminal Court on Wednesday, May 1.

Steven Hirsch/AFP via Getty Images

Editor’s note: This report includes descriptions of sexual assault.

In a New York criminal courtroom Wednesday afternoon, the Manhattan district attorney’s office told Judge Curtis Farber that they intend to pursue a new trial against disgraced former movie mogul Harvey Weinstein, after his previous New York felony sex crime conviction was overturned last week. The new trial is slated to begin sometime after Labor Day, according to Judge Curtis Farber.

Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg confirmed that his office is working on putting together a new trial, noting in a press conference Wednesday afternoon, “We are already moving forward in that matter, and having conversations with survivors, centering their well-being and pursuing justice.”

The 72-year-old Weinstein was rolled into court Wednesday in a wheelchair. After his conviction was overturned last week, he was transferred from the Mohawk Correctional Facility in upstate New York, where he had been serving a 23-year sentence, to Manhattan’s Bellevue Hospital for monitoring and treatment. During Wednesday’s hearing, Farber remanded Weinstein back into custody.

In comments during a press conference after the hearing, one of Weinstein’s lawyers, Arthur Aidala, observed, “Mr. Weinstein is clearly physically not in good health,” and added, “Mentally, he is fine – as sharp as a tack, but physically he is breaking down.”

Aidala also reiterated Weinstein’s innocence, saying: “We have a tremendous sense of relief that we’re back here. The most obvious difference is the judge that we’re before.”

Weinstein’s previous conviction in New York was overturned after the state’s Court of Appeals decreed that Weinstein had not received a fair trial, in part because the judge in that trial, James Burke, had allowed testimony from women whose allegations were not part of the charges. (These women’s testimonies were allowed by Burke as so-called “Molineux witnesses,” or “prior bad act witnesses.” Legal experts say that because the bar for Molineux witnesses can be highly subjective, their use leaves verdicts more open to legal challenges.

However, in Feb. 2023, Weinstein was also convicted of rape and sexual assault in a separate trial in Los Angeles; he has been sentenced to a 16-year prison term in California, to be served after the end of his New York imprisonment. Weinstein’s lawyers say they are appealing the California conviction as well. The brief for that appeal is due to the court later this month.

It is unclear whether all the women whose accusations were part of the first round of New York charges will be willing to testify again in front of a new jury. Attorney Gloria Allred, who has represented accuser Mimi Haleyi, said in a press conference Wednesday afternoon: “Mimi has not yet reached a decision whether or not she will agree to testify in the new trial. She has stated that the vacating of the [New York] conviction was retraumatizing to her, and that it will be even more traumatic to testify once again. She made an enormous sacrifice of time and emotion during the years prior to her finally taking the witness stand at the trial.”

Lifestyle

Inside the secret poker games opening doors in L.A.'s art scene

Artist Sarah Kim belongs to a poker group of up-and-coming art-world denizens. Part poker group, part art collective, they’re an equal mix of men and women, newbies and grinders, at varying levels of their creative careers.

Painter Sarah Kim realized soon after her move from New York to Los Angeles that learning Texas Hold ’Em would pay off. She’d heard whispers of an ultra-exclusive, high-stakes “art game” involving L.A.’s major artists, dealers and collectors going back decades. Trailing casino chip crumbs at gallery exhibits and artist studios, “It was clear to me that poker was a huge part of the art world in L.A.,” she said.

She tried her first hand at a game artist Isabelle Brourman hosted at Murmurs Gallery and soon fell in with an eclectic poker-playing group of local artists and curators. For Kim, whose landscape motifs tackle the anxiety of belonging, the felt-topped table became her social life raft and dealt her a newfound clarity and confidence.

“Being a woman in the art world, it’s like I’m playing the same game,” said Kim, who said thinking in bets has been one way to combat the volatile and, at times, cutthroat market. “I’m fighting for a literal seat at the table.”

Kim belongs to poker’s latest wave of underdogs pouring out from the creative cultural ferment. They’ve let the air out of the cigar-smoke-filled boys’ club and opened up the tables to a more diverse, inclusive and female-friendly pool of players. The storied L.A. poker scene — an obsession Tinseltown has self-mythologized since the Wild West — these days belongs to the emergent DIY art world. But the new guard has retained the fundamentals: a game as much about networking and camaraderie as card playing.

Poker is one of the few spectator games where the sexes compete on equal levels, yet 96% of professional players are men, according to the World Series of Poker. The series’ main event in Las Vegas last summer shattered the all-time attendance record of roughly 10,000 players. Still, it’s been nearly three decades since a woman made it to the final table.

Top row: Gallerist Eric Kim, left, a poker mentor to dozens of early-career artists; Parker Ito, flanked by two self-portraits; and artist Higinio Martinez, devouring chocolate poker chips. Bottom row: Art collector Jason Roussos, left, “#Girlboss” author-turned-venture capitalist Sophia Amoruso and Lauren Studebaker, who helped organize her poker group’s DIY exhibit “At Home in the Neon.”

“Poker is not necessarily a hobby for the frugal, which is also why I think women haven’t historically played,” said Bita Khorrami of Casinola, which outfits sleek, private poker games for the cultural in-crowd. Her collaborator, Eddie Cruz — who started the streetwear boutique Undefeated — taught her the game on the promise that she’d become a better businesswoman. Khorrami, who cut her teeth in music and sports management, said it was the financial edge she needed. “When I have to counter someone in a negotiation, I’ll take a percentage of the money” from the playing funds, she said, which informs a raise, call or fold. “Whatever you’re gonna do is by percentage,” she said of bankroll management. “And the more you do those things, the more comfortable you are with it.”

Now, she and Cruz are going all in on Casinola as the first-of-its-kind creative collective and lifestyle brand rooted in poker. She joined on one condition: to not be the only woman in the cardroom. “My mission is going to be to bring women to poker,” she recalled telling Cruz. “Poker degenerates want to play with other poker degenerates,” she said. “They don’t want to be taking time necessarily to teach someone.”

They enlisted Jason Roussos, an art collector and pokerhead, to help retain their brand of backroom chic while also selling the idea of empowerment. “When things become too heavy or too reliant on one type of energy,” like the hypermasculine bro kind, he said, “that energy can take over a space.” Having more women brings a dynamic shift to the table, and lowering the barrier for entry often begins with smaller buy-ins with proper setups and dealers. Female-only live games are another incentive, like the time Casinola sponsored a poker night for Girls Only Game Club. “People sometimes use poker as a vice or form of escapism, but we’re using it as more of a socializing tool,” Roussos said.

From left, ceramics artist Grant Levy-Lucero, gallerist Eric Kim and collector Jason Roussos are veterans of the high-stakes L.A. poker scene. These days they have more fun playing with their art-world friends, with Kim’s house as a hub.

Higinio Martinez and Liz Conn-Hollyn were among the 15 artists who contributed to the poker-themed group exhibit “At Home in the Neon,” held at Eric Kim’s house gallery.

A fraction of gallerist Eric Kim’s collection of 40,000 poker chips.

Eric Kim, who co-runs artist spaces Human Resources and Bel Ami, estimated “poker and art went gangbusters” when online gaming swelled early in the pandemic. After stay-at-home orders lifted, however, he noticed a low-grade culture shock among his friends at crowded openings and art parties. “I think a lot of people enjoyed the contained structure of socializing at a poker game,” he said.

He’s opened his doors to the arts community in the last couple of years, doling out free one-on-one coaching and hosting weekly Hold ’Em nights as a kind of league mentor. The home games draw from his years at casinos and underground venues around L.A. His collection of 40,000 poker chips helps too.

His Silver Lake setup is an equal mix of men and women, newbies and grinders, at varying levels of their careers. Turns out his learning pod had the makings of an artists collective. Kim and Lauren Studebaker, an associate director at Matthew Brown Gallery, staged a poker-themed group show last month. They exhibited work from 15 poker-playing artists around the domestic gallery and called it “At Home in the Neon,” a crib from art critic Dave Hickey’s love letter to Las Vegas.

Julianne Lee, a perfumer, infused plaster chips with a rare scent derived from whale vomit and called it “Who’s the whale” (a reference to a very rich but very bad poker player). Adam Alessi’s good-luck shrine had a rendering of Vanessa Rousso, nicknamed “the lady maverick of poker,” inside. Jake Fagundo’s “Bad Beat” depicted a couple in a warm embrace after a tough loss. “A lot of it was inside jokes for ourselves,” said Studebaker, who paraphrased a wry quote from “The Gambler” by Fyodor Dostoevsky: “You gamble with your friends because you like to see them humiliated.” The group has embraced how the game puts everyone on equal footing. “Losing in front of these people is a fast track to bonding,” she said. “I think the losing has been almost better for me than the winning.”

A stray Alexander Calder lithograph of three card players.

Artist Ava McDonough, another contributor to the poker-themed group show, hugs the pot.

The crowd in the kitchen, including collector Khoi Nguyen and actor Emile Hirsch, at gallerist Eric Kim’s poker game, held at his home. Artwork by Adam Alessi, left, Parker Ito and Grant Levy-Lucero surrounds the table.

The scene’s marquee event today is the annual World Series of Art Poker (WSOAP), a highly guarded, 12-hour Hold ’Em marathon during so-called Frieze Week, when blue-chip galleries and high-rolling collectors jet into town for art fairs and their ensuing parties. “I look forward to it all year,” said artist Parker Ito, who at last year’s heads-up showdown lost to Jason Koon, arguably the best pro poker player today.

At the fourth WSOAP in March, Jonas Wood, “the reigning prince of contemporary painting,” screamed the ceremonial, “Shuffle up and deal.” His Warholian grasp on the art world was on full display as he glad-handed arrivistes from New York and Europe, clad in a sweatsuit made of cash (taken from Warhol’s silkscreen “192 One Dollar Bills,1962”). “This is my conceptual art project,” Wood said of his stylized homage to the early-aughts poker boom, when he came of age in the glow of the 1998 gambling movie “Rounders” and ESPN’s breathless tourney coverage.

Inside, Benny Blanco had his barber give him a lineup at the table. Tobey Maguire busted early but stayed to sweat the last hand of his friend Leonardo DiCaprio. Beyond the $500 buy-in, entry into the stacked poker den has become its own kind of currency, where talk of bad beats and mucked hands replaces the usual industry chatter. The last player standing wins $30,000 and a holy-grail 18-karat gold bracelet modeled after one awarded to the winner of the World Series of Poker.

Artist Nihura Montiel has a sly poker face after winning.

The biggest bluff of the night: chocolate poker chips.

Sophia Amoruso made it to the final 25 out of 130 entrants. “Poker has taught me more patience than anything,” said the Nasty Gal founder and “Girlboss” author, now in venture capital. She’d recently started her own home game after playing after-hours at tech conferences and in VC circles. “To be at the table with the guy who founded Hustler Casino Live, that’s priceless,” she said. “Next week, he’s coming to my house, and I get to learn from him.”

The tournament’s brain trust — Jonas Wood, Eddie Cruz and Eric Kim — rounded up their splinter poker groups to join forces in 2020. “The idea was to find out who’s the best,” Wood recalled. They’d piggyback off Wood’s fabled “art game” in the studio he rented from Ed Ruscha between 2007 and 2017, a revolving door for the city’s “art illuminati,” as Kim put it. Gallerists like Jeff Poe and François Ghebaly rubbed elbows with celebrities like Ellen DeGeneres and Jack Black, and emerging artists faced off against billionaire collectors with increasing regularity.

This year, with past pros like Erik Seidel and Phil Ivey absent from the usual “pros versus Joes” lineup, Wood livestreamed the final tables on Instagram to his 154,000 followers and saw the chance to make good on his original idea to organize the only tournament of its kind — for artists, by artists. He envisioned a wild-card upset winning the biggest pot of their life. It almost happened.

The final 10 players included artists like up-and-coming painter Ross Caliendo, sculptor Matt Johnson and Wood’s ceramist wife, Shio Kusaka. The crowd roared when she was busted out in eighth place — the last woman and artist standing. Michael Heyward, chief executive of the holding company that owns Genius and Worldstar, went on to win. “I really wanted a broke artist or some unknown person to win $30,000,” Wood said.

Lifestyle

A poet searches for answers about the short life of a writer in 'Traces of Enayat'

As a young literature student in the 1990s, the Egyptian poet Iman Mersal stumbled across a copy of Love and Silence, a forgotten 1967 novel by a writer named Enayat al-Zayyat who died by suicide in her 20s — a few years before her book was released.

Mersal was taken with the book’s “fresh and refreshing” language and emotional intensity; it exerted such power over her that the moment she finished reading it, she “turned back and began again… [copying] out passages, small stand-alone texts like lights to illuminate my emotional state.” At the time, Mersal was establishing herself as a reader and writer, and felt the need to “personally celebrate the books which ‘touched’ her, as though she needed to define herself by appending her discoveries to the canon.”

Decades later, she remains engaged in that project, at least where Enayat is concerned. Now an established poet living in Canada, Mersal set out to learn as much as she could about Enayat’s life and death — enough, ideally, to write the other woman’s life story. Although she did not uncover nearly enough to achieve that goal, she still presents the resulting book, Traces of Enayat, as a biography of sorts. It isn’t. Traces of Enayat is a memoir of Mersal’s search, a slow, idiosyncratic journey through a layered, changing Cairo and through Mersal’s mind.

Mersal is a cool, restrained writer. Her prose, in Robin Moger’s translation, slips by easily, so that her moments of flaring emotion stand out. In contrast, the excerpts of Love and Silence she includes are hot with description and feeling. In one, Enayat describes feeling “at once imprisoned by this life and pulled toward new horizons. I wanted to pull this self clear, gummy with the sap of its surroundings; to tear free into a wider world.” It seems evident that Mersal chose this passage for its echo of Enayat’s story. Certainly it evokes one of Traces of Enayat‘s central questions: “Was it [Enayat’s] decision to end her life that drew me to her,” Mersal writes, “or the thought of her unrealized potential” — the wider literary world Enayat never reached? More vexing still is the question not of what draws Mersal to Enayat, but why Enayat’s hold over her is so powerful. At the end of the memoir, it’s still not clear.

Of course, Traces of Enayat is not designed to satisfy. It’s there in the title: we’re only going to get glimpses and fragments of its subject — or, really, its subjects. Mersal hides herself behind her search for Enayat; Enayat herself hides in the past. Her best friend, the actress Nadia Lutfi, remembers her vividly, but was too busy working to be fully present for some of Enayat’s bitterest disappointments; Enayat’s surviving relatives, meanwhile, recall her painful divorce and the rejection of her book by the publisher she’d hoped would release it, but they never had the emotional access to her that Nadia did.

Even Enayat’s tomb is hidden. She turns out to be buried in a side wing of a family member’s mausoleum and, after much investigating, Mersal manages to visit. This is the book’s emotional high point. Mersal weeps, not out of grief but because “standing there in front of her headstone was the high point of our relationship… the tomb was the only place where she actually was. For her life, I had to return to the archive, to the memories of the living, and my own imagination, but I felt now that at last she trusted me, that she had allowed me to reach her.” For the first time here, Mersal allows her interest in Enayat to transform on the page into a nearly mystical connection before moving swiftly away from the tomb and the scene. For the reader, this is an answer of sorts: Mersal’s link to Enayat goes in some way beyond the explicable. We can’t experience it for ourselves.

What we can experience is Mersal’s investigation of Egypt after the Nasserist revolution of 1952, the context for Enayat’s book and its disappearance. Enayat’s work and life do not fit neatly into the prevailing narrative that “Arab women writers [of the period] were primarily concerned with nationalism, that there could be no liberation for women without the liberation of the nation.” Love and Silence is about grief and romance; its author, meanwhile, had to battle sexist Nasserist divorce laws to free herself from her husband and couldn’t get the court to give her full custody of her son.

Mersal pieces this story together slowly, speculating about the role of Enayat’s divorce and one subsequent romantic relationship in the end of her life. She does archival work and visits the places still left from Enayat’s Cairo, superimposing the post-revolutionary city Enayat lived in — full of new hopes and colonial legacies — on the contemporary one she describes. These moments are, like the book’s other strands, fragments and flickers. Mersal passes over geography the way her prose tends to pass over emotion, never lingering in one place long enough to describe it in depth.

Mersal is a poet and this is, fundamentally, a poet’s strategy. A poem is, more often than not, a peek through a cracked window, a fleeting experience rather than a drawn-out one. But Traces of Enayat is a full book, and the degree to which it feels swift and partial is at once a literary achievement and a frustration. In its last passage, Mersal writes that Enayat “wants to remain free and weightless.” Maybe so. But by letting Enayat have what she wants, Mersal denies the reader a deeper experience of her own obsession.

Lily Meyer is a writer, translator, and critic. Her first novel, Short War, was published in April 2024.

-

Education1 week ago

Education1 week agoVideo: Dozens of Yale Students Arrested as Campus Protests Spread

-

World6 days ago

World6 days agoHaiti Prime Minister Ariel Henry resigns, transitional council takes power

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoLarry Webb’s deathbed confession solves 2000 cold case murder of Susan and Natasha Carter, 10, whose remains were found hours after he died

-

Politics1 week ago

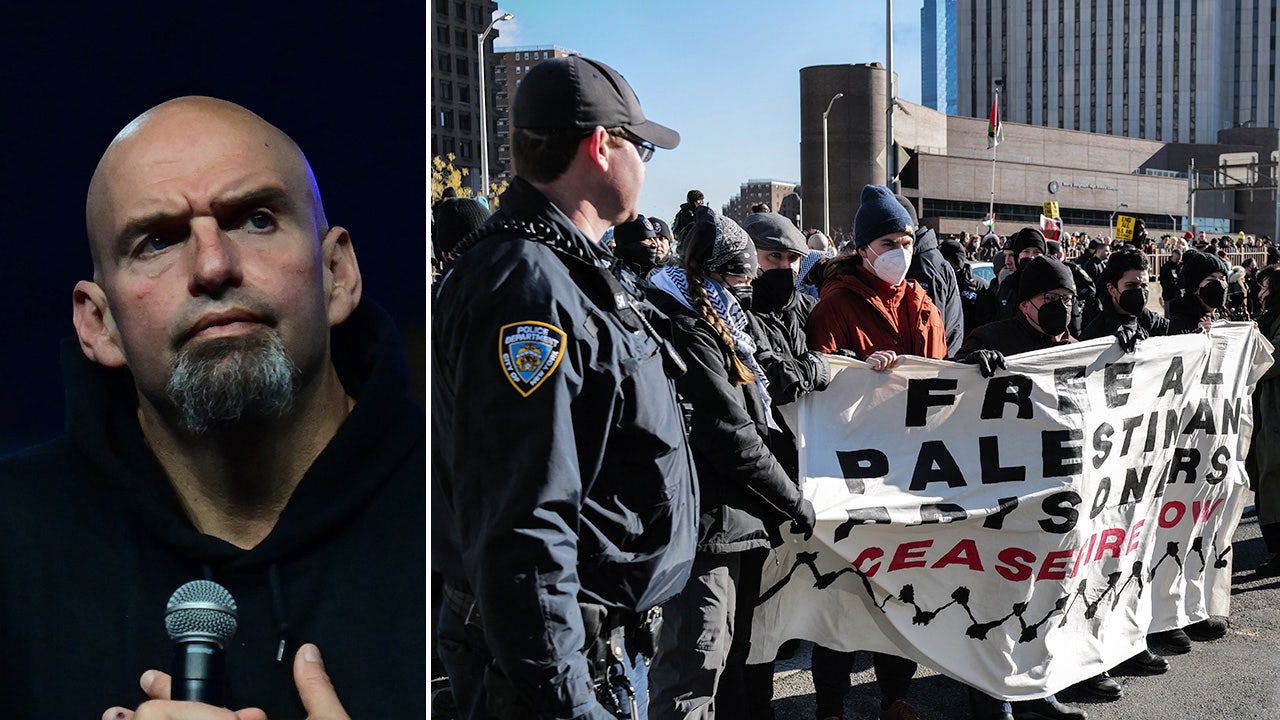

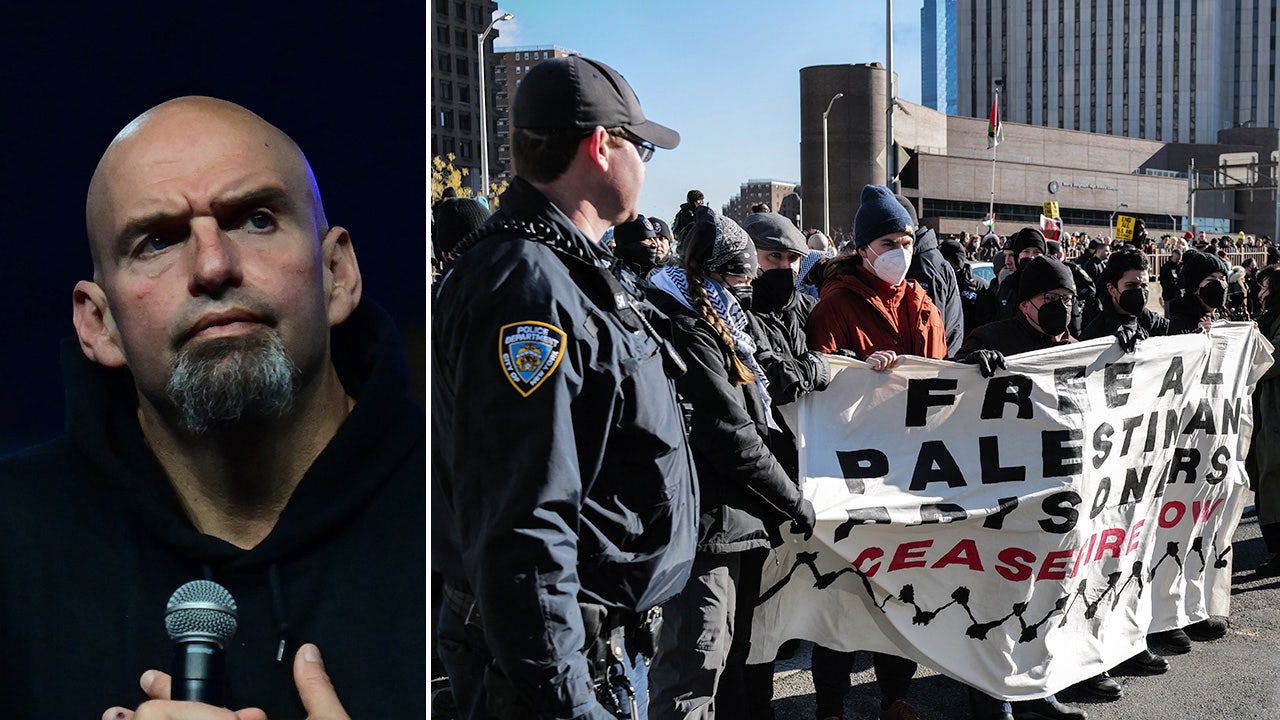

Politics1 week agoFetterman hammers 'a–hole' anti-Israel protesters, slams own party for response to Iranian attack: 'Crazy'

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoPeriod poverty still a problem within the EU despite tax breaks

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoUS secretly sent long-range ATACMS weapons to Ukraine

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoFirst cargo ship passes through new channel since Baltimore bridge collapse

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoTurkey’s Erdogan meets Iraq PM for talks on water, security and trade