Lifestyle

A Bastion of Los Angeles Hippie Culture Survived the Flames

In Topanga Canyon on Saturday morning, suspended midair from an electricity line, hung the smoldering top of a utility pole. The pole itself had burned away. Its remaining crosspieces resembled a crucifix on fire. By the time Bob Melet videotaped this eerie scene, firefighters had managed to halt the advance of flaring patches that elsewhere had been whipped into infernos.

Barely 100 yards from the front door of Mr. Melet’s store, Melet Mercantile — a destination for fashion and interior designers who for decades have tracked Mr. Melet’s idiosyncratic tastes — lay the fire line at Camp Wildwood, a disused summer camp established in the 1920s and later turned into a resort and community center by two locals, Julia and Oka Stewart. To its west and along the Pacific Coast Highway, almost everything was torched.

“The canyon is a funnel that comes right past my doorstep,” Mr. Melet said by phone from a friend’s apartment in Corona del Mar, his evacuation point. “If it had reached me, it would have wiped out the entire town.”

The fact that it had not represented the miraculous survival of an ecosystem as fragile and anomalous as it is naturally untamed. An eccentric holdout of a countercultural ethos that once went a long way toward defining the Southern California lifestyle, Topanga lies at the western limit of an extensive system of canyons resembling a series of Cyclopean knife cuts slashed into the Santa Monica mountains.

Others among the 28 canyons — Laurel, Beachwood, Runyon — may be better known beyond the Los Angeles basin, largely for their place in rock ’n’ roll history and lore. While gradually over the decades those places succumbed to the irresistible forces of gentrification, Topanga Canyon has clung to its wildness, its renegade spirit and the durable aura it retains of a one-time redoubt of bootleggers and drug runners. Bisected by a single winding mountain road, Topanga straddles the mountains and links the sprawling suburbs of the San Fernando Valley with the blue vastness of the ocean.

“One of the things we’re proudest of in Topanga is the strength of the community,” said Stefan Ashkenazy, a long time resident of the canyon. By some standards, Mr. Ashkenazy’s exclusive hotel complex, Elsewhere — built on 39 hilltop acres of what was once a vacation ranch for the Howard Johnson family — could be seen as a harbinger of gentrifying forces. That it is not owes to his efforts to keep the hotel’s vibe communitarian and local (he has offered free lodging to the area’s ad hoc firefighting teams that call themselves Heat Hawks), and its imprint light upon the land.

“Believe me, I know how lucky we are to have this holdout,” said Mr. Ashkenazy, who also owns the four-star Petit Ermitage hotel in West Hollywood.

For Emmeline Summerton, a self-taught social historian whose Instagram account, Lost Canyons LA, has become an addictive source of Los Angeles history and lore, the story of Topanga Canyon is one of improbable survival — a thoroughly wild place less than an hour’s drive from the city’s business center.

“I’m not sure how much people outside Los Angeles know about it,” she said, referring both to the canyon itself — populated by coyotes, rattlesnakes, and mountain lions — as well as a community that has long worn its ornery countercultural reputation as a badge of pride.

“There is the local, small community and a very rural feeling,” Ms. Summerton said, one still largely under the influence of the first wave of New Age pioneers. There were free-love naturist hide-outs like Elysium Fields and Sandstone Retreat, she explained, along with Moonfire Ranch, a 60-acre sanctuary established in the late 1950s by Lewis Beach Marvin III, an animal-rights activist and heir to S & H Green Stamps, a once popular grocery store reward system.

“It was very much about people living off the grid, with solar and rainwater collection,” Ms. Summerton said, and about a tolerance for oddballs and eccentrics that hung on long after a succession of real estate booms permanently altered the character of other, less remote canyons. “A lot has changed and there’s a new breed of hippie-type people out there, influencers and wellness entrepreneurs, so, yes, it’s more exclusive and expensive than in the past,” she added. “But it’s still the one canyon where you get a sense of what it has always been.”

By this she meant a refuge for renegades and outsiders, for artists like Neil Young, who wrote his landmark solo album “After the Gold Rush” at his house there; for storied ’60s groups like Canned Heat, whose members once worked as the house band at the Topanga Corral club (which burned down not once but twice); for Linda Ronstadt in the days after she quit Stone Poneys, the folk rock trio, to go solo and make music with musicians who would later form the Eagles; for the American actor Will Geer to create an open air amphitheater set in a hillside and call it the Theatricum Botanicum, a name derived from a 17th century English botanical text.

To this day in Topanga Canyon there remains an itinerant community informally known as the “Creekers,” whose members live off the grid in encampments set along creeks in the hills behind the disused Topanga Ranch Motel; residents who ride horses to do their marketing at the Topanga Creek General Store; and naturists hiking canyon roads clad in little besides sun hats and sneakers.

This, of course, was before the wildfires.

Gone on the first day of the Palisades fire was the Reel Inn, a beloved Malibu fish joint opened in 1986 by Teddy and Andy Leonard at the base of Topanga Canyon. Also gone was Cholada, a bustling Thai restaurant whose takeout was both a staple of coastal dining and the source of catered meals for the art world honchos that regularly decamp to Los Angeles for the annual Frieze art fair. Gone, too, were the Topanga Ranch Motel, a bungalow style motel complex built in 1929 by William Randolph Hearst to house railroad workers, and the Malibu Feed Bin, a holdout from an era when this stretch of the California coast was still largely agrarian.

Entire hillsides and washes were reduced to ashes and, later that same afternoon so, too, was an entire stretch of multimillion dollar homes improbably perched oceanside where the canyons meet the water along Pacific Coast Highway.

“If you’re ever going to use the word surreal,” Mr. Melet said of the devastation, “it was surreal.”

What seemed almost miraculous, given the surrounding destruction, was that the fires failed to reach the Theatricum Botanicum, and left unscathed the Inn of the Seventh Ray, whose dining tables are set on stone terraces by a creek side and whose gift shop is filled with crystals and mystical arcana.

“So far Topanga has mainly been spared,” the actress Wendie Malick said by phone from her ranch set on a ridge above Topanga.

“The winds were in our favor,” she added. “Though we’re not out of the woods yet. Things can change on a dime.”

And, indeed, the cyclonic winds — biblical, raging, like nothing in memory — started up again on Monday.

“The fires didn’t get to us last week,” said Nick Fouquet, a French American designer whose Western-style hats are favored by celebrities including Tom Brady, Rihanna, J. Balvin and LeBron James. When the first alert came last week, Mr. Fouquet raced up the coast from his business’s headquarters in Venice to the geodesic dome in Topanga that he calls home and, aided by a band of locals pumped out his swimming pool to soak his house and its surroundings.

It was a scene being repeated throughout the canyon, Mr. Fouquet said, neighbors on a mission of “house triage,’’ putting out small burns before they could grow. Videos Mr. Fouquet sent this reporter from the early days of the fire showed crimson flames crowning a ridge less than a quarter-mile from his property line. “The wind, the firefighters, a myriad of factors have been on our side,” said Mr. Fouquet.

Among those factors were the triage efforts of a tight knit community that stayed put despite evacuation orders and that banded together — as it has consistently across the decades when the canyon was visited by the wildfires, earthquakes, mudslides and rockfalls that are a fact of life in a seismically unstable coastal desert perched at a continent’s edge.

“Topanga always felt like the ugly stepchild no one cares about,” Mr. Fouquet said, while acknowledging the role in his current reprieve of both firefighters and fate. “We’re used to doing things for ourselves.”

Lifestyle

10 books we’re looking forward to in early 2026

Two fiction books about good friends coming from different circumstances. Two biographies of people whose influence on American culture is, arguably, still underrated. One Liza Minnelli memoir. These are just a handful of books coming out in the first few months of 2026 that we’ve got our eye on.

Fiction

Autobiography of Cotton, by Cristina Rivera Garza, Feb. 3

Garza, who won a Pulitzer in 2024 for memoir/autobiography, actually first published Autobiography of Cotton back in 2020, but it’s only now getting an English translation. The book blends fiction with the author’s own familial history to tell the story of cotton cultivation along the U.S.-Mexico border.

Crux, by Gabriel Tallent, Jan. 20

Tallent’s last novel, My Absolute Darling, was a harrowing coming of age story about a teenage girl surviving her abusive survivalist father. But it did find pockets of beauty in the outdoors. Tallent’s follow up looks to be similarly awestruck by nature. It’s about two young friends, separated by class and opportunity, but bound together by a love of rock climbing.

Half His Age, by Jennette McCurdy, Jan. 20

The former iCarly actress’ bracing and brutally honest memoir, I’m Glad My Mom Died, was a huge hit. It spent weeks on bestseller’s lists, and is being adapted into a series for Apple TV+. Now McCurdy’s set to come out with her fiction debut, about a teenage girl who falls for her high school creative writing teacher.

Kin, by Tayari Jones, Feb. 24

Similarly to Crux, Kin also follows two friends across the years as options and opportunities pull them apart. The friends at the center of this book are two women who grew up without moms. Jones’ last novel, 2018’s An American Marriage, was a huge hit with critics.

Seasons of Glass & Iron: Stories, by Amal El-Mohtar, March 24

El-Mohtar is an acclaimed science-fiction writer, and this book is a collection of previously published short stories and poetry. Many of the works here have been honored by the big science-fiction/fantasy awards, including the titular story, which is a feminist re-telling of two fairy tales.

Nonfiction

A Hymn to Life: Shame Has to Change Sides, by Gisèle Pelicot, Feb. 17

Pelicot’s story of rape and sexual assault – and her decision to wave anonymity in the trial – turned her into a galvanizing figure for women across the world. Her writing her own story of everything that happened is also a call to action for others to do the same.

Cosmic Music: The Life, Art, and Transcendence of Alice Coltrane, by Andy Beta, March 3

For decades, the life and work of Alice Coltrane has lived in the shadow of her husband, John Coltrane. This deeply researched biography hopes to properly contextualize her as one of the most visionary and influential musicians of her time.

Football, by Chuck Klosterman, Jan. 20

One of our great essaysists and (over?) thinkers turns his sights onto one of the last bits of monoculture we’ve got. But in one of the pieces in this collection, Klosterman wonders, how long until football is no longer the summation of American culture? But until that time comes, there’s plenty to dig into from gambling to debates over the true goat.

Kids, Wait Till You Hear This! by Liza Minnelli, with Michael Feinstein, March 20

Minnelli told People that previous attempts at telling her story “didn’t get it right,” so she’s doing it herself. This new memoir promises to get into her childhood, her marriages, and her struggles with substance abuse.

Tom Paine’s War: The Words that Rallied a Nation and the Founder of Our Time, by Jack Kelly, Jan. 6

If you haven’t heard, it’s a big birthday year for America. And it’s a birthday that might not have happened if not for the words of Thomas Paine. This new book from historian Jack Kelly makes the argument that Paine’s words are just as important and relevant to us today.

Lifestyle

At 70, she embraced her Chumash roots and helped revive a dying skill

Around 1915, the last known Chumash basket maker, Candelaria Valenzuela, died in Ventura County, and with her went a skill that had been fundamental to the Indigenous people who lived for thousands of years in the coastal regions between Malibu and San Luis Obispo.

A century and two years later, 70-year-old Santa Barbara native Susanne Hammel-Sawyer took a class out of curiosity to learn something about her ancestors’ basket-making skills.

Hammel-Sawyer is 1/16 Chumash, the great-great-great-granddaughter of Maria Ysidora del Refugio Solares, one of the most revered ancestors of the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians for her work in preserving its nearly lost Samala language.

But Hammel-Sawyer knew nearly nothing about Chumash customs when she was a child. As a young mother, she often took her four children to the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History, where she said she loved to admire the museum’s extensive collection of Chumash baskets, “but I had no inkling I would ever make them.”

Nonetheless, today, at age 78, Hammel-Sawyer is considered one of the Santa Ynez Band’s premier basket makers, with samples of her work on display at three California museums.

Short, reddish brown sticks of dried basket rush sit in a small basket in Susanne Hammel-Sawyer’s kitchen, waiting to be woven into one of her baskets. The reddish color only appears at the bottom ends of the reeds, after they dry, so she saves every inch to create designs in her baskets. “These are my gold,” she says.

(Sara Prince / For The Times)

She grows the basket rush (Juncus textilis) reeds that make up the weaving threads of her baskets in a huge galvanized steel water trough outside her Goleta home and searches in the nearby hills for other reeds: primarily Baltic rush (Juncus balticus) to form the bones or foundation of the basket and skunk bush (Rhus aromatica var. trilobata) to add white accents to her designs.

All her basket materials are gathered from nature, and her tools are simple household objects: a large plastic food storage container for soaking her threads and the rusting lid of an old can with different-sized nail holes to strip her reeds to a uniform size. Her baskets are mostly the yellowish brown color of her main thread, strips of basket rush made pliant after soaking in water.

The basket reeds often develop a reddish tint at the bottom part of the plant when they’re drying. “Those are my gold,” she said, because she uses those short ends to add reddish designs. Or sometimes she just weaves them into the main basket for added flair.

The only other colors for the baskets come from skunk bush reeds, which she has to split and peel to reveal the white stems underneath, and some of the basket reeds that she dyes black in a big bucket in her backyard.

“This is my witches’ brew,” she said laughing as she stirred the viscous inky liquid inside the bucket. “We have to make our own from anything with tannin — oak galls, acorns or black walnuts — and let it sit to dye it black.”

Hammel-Sawyer is remarkable not just for her skill as a weaver, but her determination to master techniques that went out of practice for nearly 100 years, said anthropologist and ethnobotanist Jan Timbrook, curator emeritus of ethnography at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History, which claims to have the world’s largest museum collection of Chumash baskets.

“Susanne is one of the very few contemporary Chumash people who have truly devoted themselves to becoming skilled weavers,” said Timbrook, author of “Chumash Ethnobotany: Plant Knowledge Among the Chumash People of Southern California.” “Many have said they’d like to learn, but once they try it and realize how much time, patience and practice it requires … they just can’t keep it up.”

Susanne Hammel-Sawyer adds another row to her 35th basket, working from a straight back chair in her small living room, next to a sunny window and the tiny table where she keeps all her supplies.

(Sara Prince / For The Times)

In her eight years, Hammel-Sawyer has made just 34 baskets of various sizes (she’s close to finishing her 35th), but she’s in no hurry.

“People always ask how long it takes to make a basket, and I tell them what Jan Timbrook likes to say, ‘It takes as long as it takes,’” Hammel-Sawyer said. “But for me, it’s a way of slowing down. I really object to how fast we’re all moving now, and it’s only going to get faster.”

She and her husband, Ben Sawyer, have a blended family of five children and nine grandchildren, most of whom live near their cozy home in Goleta. Family activities keep them busy, but Hammel-Sawyer thinks it’s important for her family to know she has other interests too.

“When you’re older, you have to be able to find a passion, something your children and grandchildren can see you do, not just playing golf or going on cruises, but doing something that matters,” she said. “I wish my grandmother and my father knew I was doing this because it’s a connection with our ancestors, but it’s also looking ahead, because these baskets I’m making will last a very long time. It’s something that comes from my past that I’m giving to family members to take into the future, so it’s worth my time.”

Also, this isn’t a business for Hammel-Sawyer. Her baskets are generally not for sale because she only makes them for family and friends, she said. The baskets at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History and the Santa Ynez Chumash Museum and Cultural Center belong to family members who were willing to loan them out for display. The Chumash museum does have some of Hammel-Sawyer’s baskets for sale in its gift shop, which she said she reluctantly agreed to provide after much urging, so the store could offer more items made by members of the Band.

For the last eight years, Susanne Hammel-Sawyer has used the same old can lid, punched with nail holes of various sizes, to strip her moistened basket threads to a consistent size.

(Sara Prince / For The Times)

The only other basket she’s sold, she said, was to the Autry Museum of the American West, because she was so impressed by its exhibits involving Indigenous people. “I just believe so strongly in the message the Autry is giving the world about what really happened to Indigenous people, I thought I would be proud to have something there,” she said.

Making a basket takes so long, Hammel-Sawyer said, that it’s important for her to focus on the recipient, “so while I’m making it, I can think about them and pray about them. When you know you’re making a basket for someone, it has so much more meaning. And I’m so utilitarian, I always hope someone will use them.”

For instance, she said, she made three small baskets for the children of a friend and was delighted when one used her basket to carry flower petals to toss during a wedding. Almost any use is fine with her, she said, except storing fruit, because if the fruit molds, the basket will be ruined.

Baskets were a ubiquitous part of Chumash life before the colonists came. They used them for just about everything, from covering their heads and holding their babies to eating and even cooking, Timbrook said. They put hot rocks into their tightly woven baskets, along with food like acorn mush, to bring the contents to boil.

“People think pottery is a higher form of intellectual achievement, but the thing is, baskets are better than pottery,” Timbrook said. “They’ll do anything pottery will do; you can cook in them and store things in them, and when you drop them, they don’t break.”

1. Tule reeds that grows in the yard in preparation of basket weaving. 2. Susanne Hammel-Sawyer weaves a basket. 3. A basket sits during a break in weaving with tools on a table. (Sara Prince / For The Times)

After Hammel-Sawyer’s first marriage ended, she worked as an assistant children’s librarian in Santa Barbara and met a reference librarian named Ben Sawyer. After their friendship turned romantic, they married in 1997 and moved, first to Ashland, Ore., then Portland, and then the foothills of the Sierras in Meadow Valley, Calif., where they took up organic farming for a dozen years.

Meadow Valley’s population was 500, and the big town was nearby Quincy, the county seat, with about 5,000 residents, but it still had an orchestra and she and her husband were both members. She played cello and he viola, not because they were extraordinary musicians, she said, but because “we played well enough, and if we wanted an orchestra, we would have to take part. I loved how strong people were there. We were all more self-sufficient than when we lived in the city.”

The Sawyers moved back to Santa Barbara in 2013, the year after her father died, to help care for her mother, who had developed Alzheimer’s disease. And for the next four years, between caring for her mother, who died in 2016, and the birth of her grandchildren, family became her focus.

But in 2017, the year she turned 70, Hammel-Sawyer finally had the space to begin looking at other activities. Being she’s 1/16 Chumash, she was eligible for classes taught by the Santa Ynez Band. She had seen several class offerings come through over the years, but nothing really captured her interest until she saw a basket-weaving class offered by master basket maker Abe Sanchez, as part of the tribe’s ongoing effort to revive the skill among its members.

Most Chumash baskets have some kind of pattern, although today people have to guess at the meaning of the symbols, Timbrook said. Some look like squiggles, zigzaggy lightning bolts or sun rays, but the wonder, marveled Hammel-Sawyer, is how the makers were able to do the mental math to keep the patterns even and consistent, even for baskets that were basically everyday tools.

Hammel-Sawyer is careful to follow the basics of Chumash weaving, using the same native plants for her materials and weaving techniques that include little ticks of contrasting color stitches on the rim, something visible in most Chumash baskets. She keeps a good supply of bandages for her fingers because the reeds have sharp edges when they’re split, and it’s easy to get the equivalent of paper cuts.

She keeps just two baskets at her house — her first effort, which “wasn’t good enough to give anybody,” she said, laughing — and a basket hat started by her late sister, Sally Hammel.

This basket hat was started by Susanne Hammel-Sawyer’s sister, Sally Hammel, but the stitches became ragged and uneven after Sally began treatment for cancer. She was so distressed by her work, she hid the unfinished basket, but after she died, Hammel-Sawyer found it and brought it home to complete it. It’s one of only two baskets she’s made that she keeps in her home.

(Sara Prince / For The Times)

“Sally was an artist in pottery, singing, acting and living life to the fullest,” Hammel-Sawyer said, and she was very excited to learn basketry. Her basket hat started well, but about a third of the way in, she got cancer “and her stitches became more and more ragged. She had trouble concentrating, trouble preparing materials,” Hammel-Sawyer said. “Everything became so difficult that she hid the basket away. I know she didn’t even want to look at it, let alone have anyone else see it.”

After her sister died in 2020, Hammel-Sawyer had a hard time finding the basket, “but I did, and I asked my teacher what to do, and he said, ‘Just try to make sense of her last row’ … So that’s what I did.” She added a thick black-and-white band above the ragged stitches and finished the blond rim with the traditional contrasting ticking.

The hat rests now above the window in Hammel-Sawyer’s living room, except when she wears it to tribal events.

“Sally and I were very close, and I think she’d just be happy to know it was finished and appreciated,” Hammel-Sawyer said. “Even the hard parts … deeply appreciated.”

Lifestyle

Nick Reiner’s attorney removes himself from case

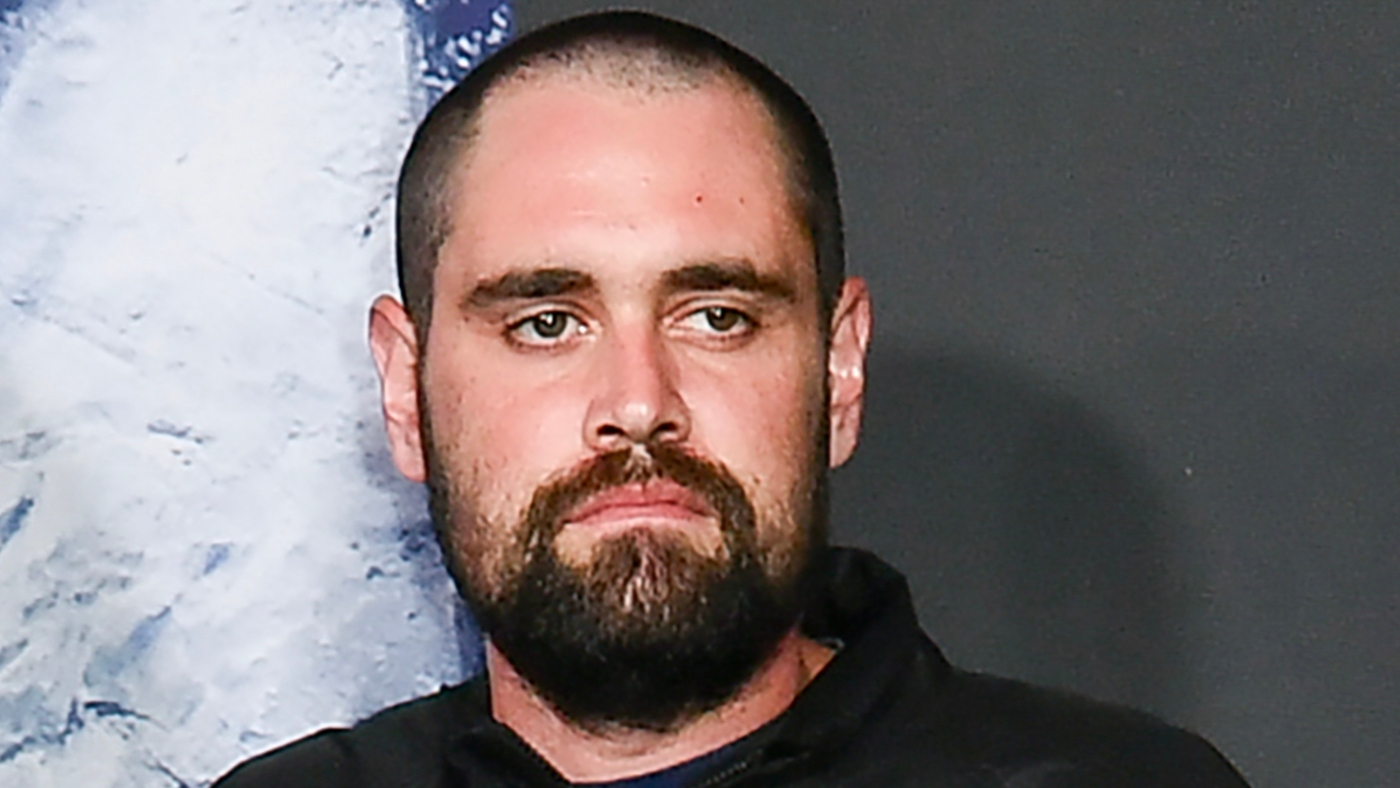

Nick Reiner arrives at the premiere of Spinal Tap II: The End Continues on Tuesday, Sept. 9, 2025, in Los Angeles.

Richard Shotwell/Invision/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Richard Shotwell/Invision/AP

LOS ANGELES – Alan Jackson, the high-power attorney representing Nick Reiner in the stabbing death of his parents, producer-actor-director Rob Reiner and photographer Michele Singer Reiner, withdrew from the case Wednesday.

Reiner will now be represented by public defender Kimberly Greene.

Wearing a brown jumpsuit, Reiner, 32, didn’t enter a plea during the brief hearing. A judge has rescheduled his arraignment for Feb. 23.

Following the hearing, defense attorney Alan Jackson told a throng of reporters that Reiner is not guilty of murder.

“We’ve investigated this matter top to bottom, back to front. What we’ve learned and you can take this to the bank, is that pursuant to the law of this state, pursuant to the law in California, Nick Reiner is not guilty of murder,” he said.

Reiner is charged with first-degree murder, with special circumstances, in the stabbing deaths of his parents – father Rob, 78, and mother Michele, 70.

The Los Angeles coroner ruled that the two died from injuries inflicted by a knife.

The charges carry a maximum sentence of death. LA County District Attorney Nathan Hochman said he has not decided whether to seek the death penalty.

“We are fully confident that a jury will convict Nick Reiner beyond a reasonable doubt of the brutal murder of his parents — Rob Reiner and Michele Singer Reiner … and do so unanimously,” he said.

Last month, after Reiner’s initial court appearance, Jackson said, “There are very, very complex and serious issues that are associated with this case. These need to be thoroughly but very carefully dealt with and examined and looked at and analyzed. We ask that during this process, you allow the system to move forward – not with a rush to judgment, not with jumping to conclusions.”

The younger Reiner had a long history of substance abuse and attempts at rehabilitation.

His parents had become increasingly alarmed about his behavior in the weeks before the killings.

Legal experts say there is a possibility that Reiner’s legal team could attempt to use an insanity defense.

Defense attorney Dmitry Gorin, a former LA County prosecutor, said claiming insanity or mental impairment presents a major challenge for any defense team.

He told The Los Angeles Times, “The burden of proof is on the defense in an insanity case, and the jury may see the defense as an excuse for committing a serious crime.“

“The jury sets a very high bar on the defendant because it understands that it will release him from legal responsibility,” Gorin added.

The death of Rob Reiner, who first won fame as part of the legendary 1970s sitcom All in the Family, playing the role of Michael “Meathead” Stivic, was a beloved figure in Hollywood and his death sent shockwaves through the community.

After All in the Family, Reiner achieved even more fame as a director of films such as A Few Good Men, Stand By Me, The Princess Bride and When Harry Met Sally. He was nominated for four Golden Globe Awards in the best director category.

Rob Reiner came from a show business pedigree. His father, Carl Reiner, was a legendary pioneer in television who created the iconic 1960s comedy, The Dick Van Dyke Show.

-

Detroit, MI5 days ago

Detroit, MI5 days ago2 hospitalized after shooting on Lodge Freeway in Detroit

-

Technology2 days ago

Technology2 days agoPower bank feature creep is out of control

-

Dallas, TX4 days ago

Dallas, TX4 days agoDefensive coordinator candidates who could improve Cowboys’ brutal secondary in 2026

-

Health4 days ago

Health4 days agoViral New Year reset routine is helping people adopt healthier habits

-

Nebraska2 days ago

Nebraska2 days agoOregon State LB transfer Dexter Foster commits to Nebraska

-

Iowa2 days ago

Iowa2 days agoPat McAfee praises Audi Crooks, plays hype song for Iowa State star

-

Nebraska2 days ago

Nebraska2 days agoNebraska-based pizza chain Godfather’s Pizza is set to open a new location in Queen Creek

-

Entertainment1 day ago

Entertainment1 day agoSpotify digs in on podcasts with new Hollywood studios