Oregon

Oregon Democrat at Risk as 5 States Hold US House Primaries

By BRIAN SLODYSKO, Related Press

WASHINGTON (AP) — After years of irking his colleagues, a longtime average Democratic congressman faces his stiffest major problem but in Oregon.

In North Carolina, a rising Republican star beset by private {and professional} scandals is trying to eke out a win in his GOP-leaning district.

And throughout the U.S., an exodus of Home Democrats has put a half dozen congressional seats up for grabs.

The outcomes of Home major contests held in Idaho, Kentucky, North Carolina, Oregon and Pennsylvania aren’t prone to provide hints of which get together will management the chamber subsequent 12 months. However they may provide perception concerning the path wherein every get together is headed after two years of unified Democratic management of Washington.

Political Cartoons

A rundown of races to maintain monitor of:

Six open congressional seats up for grabs Tuesday have been vacated by Democrats who opted to retire or search larger workplace quite than run once more.

Mass exoduses from Congress aren’t unusual earlier than midterm elections, when voters have traditionally punished the get together of the sitting president. However this 12 months, an unusually excessive 31 Home Democrats have introduced they won’t run once more.

Most are protected Democratic seats, or at the least lean that manner. Which means they seemingly will not play a job in figuring out which get together controls the Home subsequent 12 months. However the retirements symbolize a serious lack of expertise, data and affect on the Capitol for Home Democrats and underscore the get together’s deep sense of pessimism about their prospects in November.

A western Pennsylvania seat held by Rep. Conor Lamb is without doubt one of the few that’s considered as aggressive. He opted to run for the state’s open U.S. Senate seat quite than search reelection.

In Louisville, Kentucky, state Senate Minority Chief Morgan McGarvey and progressive state Rep. Attica Scott are vying to interchange retiring Home Funds Committee Chair John Yarmuth, who was first elected in 2006.

In Oregon, the retirement of Home Transportation Committee Chair Peter DeFazio has set off a scramble. State Labor Commissioner Val Hoyle is a front-runner for the protected Democratic seat.

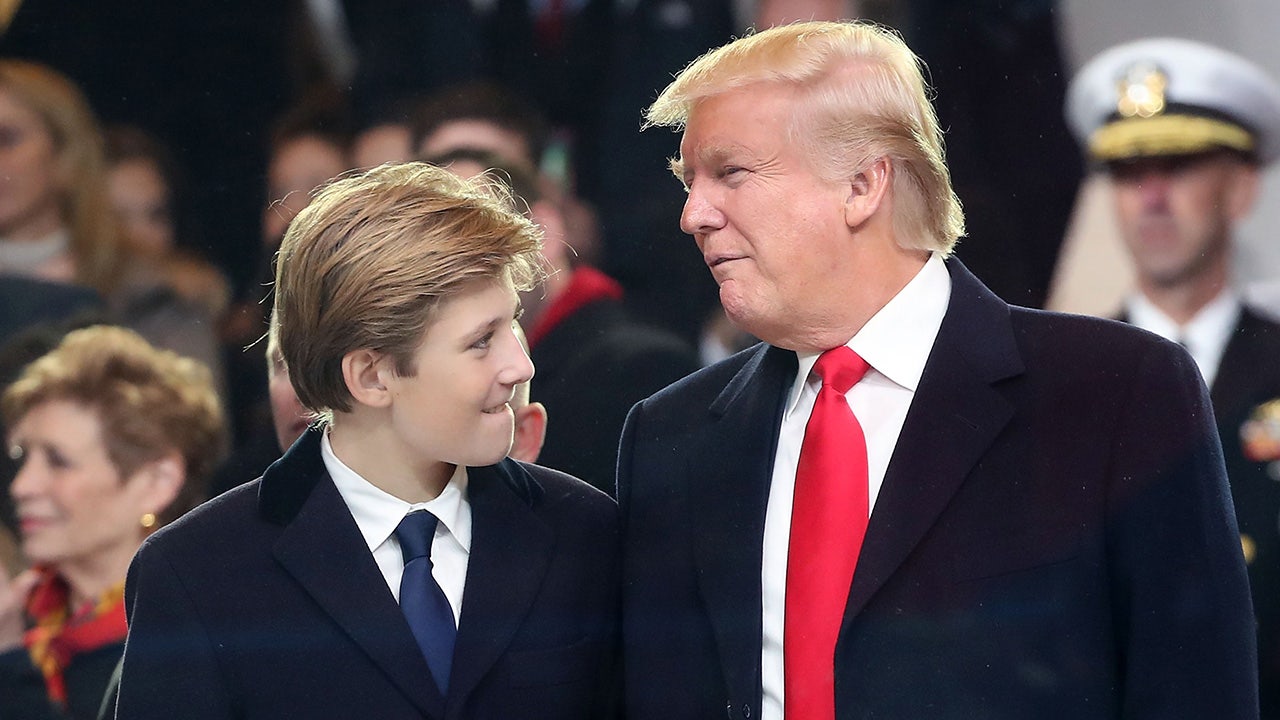

Madison Cawthorn’s sudden 2020 win made him the youngest member of Congress and a rising Republican star. Then the scandals began to pile up.

The 26-year-old conservative has drawn condemnation from senior GOP leaders in Washington in addition to North Carolina. He now faces an intense major problem as he seeks reelection to his western North Carolina district.

The race has drawn over a half-dozen candidates, who might break up the anti-Cawthorn vote. However Cawthorn has the help of the Republican whose opinion could carry essentially the most affect.

“Lately, he made some silly errors, which I don’t imagine he’ll make once more,” former President Donald Trump mentioned in an announcement on Monday. “Let’s give Madison a second likelihood.”

A TEST FOR MODERATES IN OREGON

U.S. Rep. Kurt Schrader, a average Oregon Democrat, has usually been at odds together with his get together. He likened Trump’s second impeachment trial to a “lynching,” voted in opposition to Nancy Pelosi for Home speaker in 2019, and helped contribute to the collapse of President Joe Biden’s social spending agenda together with his opposition to components of it.

Regardless of that, Schrader, a seven-term congressman, received Biden’s endorsement forward of Tuesday’s major in his newly redrawn district. The district is barely much less Democratic than earlier than and incorporates solely about half of the voters who beforehand elected him to Congress.

Progressive challenger Jamie McLeod-Skinner has the backing of the native Democratic events in all 4 counties lined by the seat. If she wins, she might face a tricky normal election marketing campaign in opposition to the Republican victor.

Republican U.S. Rep. Mike Simpson of Idaho confronted conservative legal professional Bryan Smith on the poll in 2014 and smoked him by greater than 20 share factors. This time may very well be completely different.

Simpson has infected some hard-line conservatives as a result of he supported an investigation into the origins of the Jan. 6, 2021, assault on the U.S. Capitol by a mob of Trump supporters. He additionally known as Trump “unfit to be president” again in 2016.

Now the 12-term congressman has drawn a handful of major challengers, together with Smith, for the 2nd Congressional District that he’s represented since 1999.

One of many greatest points within the race is native. Simpson advocated for breaching dams alongside the Snake River to assist shield salmon. Smith says it could devastate the state.

“He’s mainly declared struggle on farmers, ranchers and households,” Smith advised the Idaho Falls Submit Register.

CRYPTOCURRENCY IN CONGRESS

Large spending by a cryptocurrency billionaire helped catapult political newcomer Carrick Flynn to front-runner standing within the crowded Democratic major for Oregon’s new sixth Congressional District, close to Portland.

Flynn has mentioned he doesn’t have sturdy emotions about cryptocurrency, a trade that has spent large this 12 months to elect their most popular candidates. However he is been the beneficiary of a $10 million promoting marketing campaign from the group Shield Our Future and is the uncommon major candidate to win the backing of Home Democratic management.

Loretta Smith, a Carrick rival who desires to be the primary Black lady from Oregon elected to Congress, mentioned it’s “disrespectful and it’s unsuitable” for Pelosi’s marketing campaign arm to get entangled.

She and different Democrats within the race criticized the transfer throughout a joint information convention the place they decried it as an insult to Oregon voters.

Within the nine-person major, Carrick seems locked in a detailed race with state Rep. Andrea Salinas, a three-term state lawmaker who would develop into Oregon’s first Hispanic lady in Congress if elected.

Observe AP for full protection of the midterms at https://apnews.com/hub/2022-midterm-elections and on Twitter at https://twitter.com/ap_politics.

Copyright 2022 The Related Press. All rights reserved. This materials might not be revealed, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Oregon

Central Oregon experiences a spectacular celestial event – the Northern lights – KTVZ

BEND, Ore. (KTVZ) — People stayed up late Friday night to catch a glimpse of a natural phenomenon — the Northern lights. If you went outside your door last night, you probably saw the dazzling Northern lights. Layers of pink, green, blue or orange painting the night sky.

For Central Oregon, it’s a treat to see the Northern lights. But for people as far south as Puerto Rico and Florida, this may be a once-in-a-lifetime chance.

The director of the Cascade Astronomy and Rocketry Academy, Bob Grossfeld, explained how this celestial event was possible.

Grossfeld said, “This event took place because of a solar eruption that took place a few days ago. And that material from the sun took about 36 to 48 hours to get to the earth. So we knew it was coming. And we know there are some that are going to follow that. So there have been large eruptions from the sun during what we call solar maximum. And so every 11 years we have a maximum of solar activity. This just happens to be the peak. So on 24-25, we expect to see this type of solar activity.”

Electronic devices like GPS that require satellite communication may be interfered with by an electrical storm like this.

Grossfeld said the lights will be most visible Saturday and Sunday nights. He predicts that your best chance to spot the lights will likely be between 11:30 p.m. and 12:30.

Oregon

Logos Public Charter's “Rogue Pack” takes first in Oregon Envirothon – KOBI-TV NBC5 / KOTI-TV NBC2

Skip to content

Oregon

How should the Owyhee Canyonlands be protected? One coalition urges action on monument designation. • Idaho Capital Sun

This article originally appeared on Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, independent news organization that covers climate, energy and the environment. It is republished with permission. Sign up for their newsletter here.

OWYHEE CANYONLANDS, Ore. — Drive 50 miles from Boise, past the suburbs, exurbs and farms into Oregon, and you’ll find yourself in the largest conservation opportunity left in the continental U.S.

In the Owyhee Canyonlands, Western sagebrush landscapes surround rock formations reminiscent of the Colorado Plateau, leading some to liken it to the Grand Canyon. It stretches across roughly 7 million acres of high desert in Oregon, Idaho and Nevada. Roughly a third of that landscape is high-quality wilderness — more land than in many existing national parks — with no roads or cell service.

Some of the last pristine sections of the rapidly declining sagebrush habitat that once dominated much of the Western U.S., the Owyhee Canyonlands — named for the phonetic pronunciation of Hawaii after three island natives were lost in the wilderness and never found — have remained wild despite little federal protection. “Its remoteness protected it,” said Ryan Houston, the executive director of the Oregon Natural Desert Association, an environmental group leading efforts to protect the area.

But the Owyhee is under threat. The population in Idaho’s Treasure Valley and Boise to the north of the canyonlands is growing, with suburbs expanding into the area. The south is home to a new mining boom, with the second approved lithium mine in the U.S. now under construction just over the Nevada border. In between, invasive weeds have invaded the area, sparking bigger and hotter wildfires that are turning portions of the region from sagebrush to grasslands, threatening the entire ecosystem and the cultural sites found throughout the canyonlands that are important to local Indigenous tribes.

For decades, groups have pushed to protect the Owyhees and come up short. Current legislation introduced by Oregon’s senators to protect the area has broad local support but stalled in Congress. So a growing grassroots coalition is taking matters into its own hands, urging President Joe Biden to designate just over 1 million acres in the Owyhee Canyonlands as a national monument under the Antiquities Act, which allows presidents to protect naturally or historically significant places without Congress.

“It used to be you could find a place like this, write a bill and protect it,” said Aaron Kindle, the director of sporting advocacy at the National Wildlife Federation, who has helped lead the conservation group’s involvement in the monument push. But times have changed, he said, so communities and conservationists are turning to the nation’s highest office, rather than just representatives from their state.

They believe now is their best chance to protect this stretch of land in eastern Oregon. In his first few weeks in office, Biden issued an executive order tasking his administration to conserve 30 percent of America’s lands and waters from development by 2030, establishing conservation as key to addressing the climate crisis. That led to the America the Beautiful initiative, which outlined how to work with local community stakeholders to protect biodiversity, the natural resources needed to address climate change and Americans’ access to wild spaces.

The initiative has signaled to local communities, tribes and environmental groups a willingness of the Biden administration to work with them to protect culturally and environmentally important spaces from unwanted developments like mining for uranium and lithium, fossil fuel production and the development of renewable energy projects, all of which are possible in the Owyhee Canyonlands, where the federal government owns much of the land.

Since 2021, the Biden administration has established five new national monuments, but advocates worry the time is running out for the nation to conserve more land in an election year.

“If somebody other than Biden is elected, the opportunity for a monument is lost,” Houston said.

It’s a sentiment shared across the country, with local advocates urging Biden to designate nine national monuments in seven states. On May 2, Biden expanded the size of the San Gabriel Mountains and Berryessa Snow Mountain national monuments in California, the latest in his conservation efforts. All but two of the proposed new monuments would be in the western half of the country, which holds most of the conservation opportunities remaining in the continental U.S. in the vast undeveloped federal lands overseen by the Bureau of Land Management.

As Congress has become more polarized over the past decade, less land has been protected, with conservation becoming a hot-button topic despite broad public support. Republicans often oppose protections that might limit grazing, mining and drilling on public lands. That has led to presidents, typically Democrats, conserving more land using the Antiquities Act, with Biden on pace to set the record for the most new national monument proclamations by a first-term president.

“Congress is just not a very effective tool for protecting land anymore, legislation is not working as well as it used to for conservation,” said Kate Groetzinger, the communications manager for the Center for Western Priorities, a conservation and advocacy organization focused on Western public lands that has tracked Biden’s climate and conservation efforts in the West. “So national monuments really are the most effective tool that we have as a country to protect biodiversity and ward off this extinction crisis.”

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX

‘A lot of culture and a lot of bloodshed’

Karl Findling doesn’t mince words.

The former firefighter has lived, hunted, fished and hiked in the Owyhee his whole life. “The reality on the ground is that it’s not in good shape,” he said. It’s a point he drives home when guiding visitors through the canyonlands and speaking at public meetings throughout the region.

He’s seen the land change firsthand. After college, Findling worked on the BLM’s fire crew in the area during the summer. The biggest fires he ever saw then burned little more than 30,000 acres in the Canyonlands. They now reach 10 times that size.

To the untrained eye, it all appears to be a vast untouched landscape, with rolling hills covered in reddish-purple grass in the spring. But those like Findling who have lived here for decades see the rapid change the Owyhee is undergoing. The verdant hills show an invasive species — cheatgrass — has invaded the area, outcompeting native vegetation by fueling bigger and hotter wildfires that enable them to spread further into the Canyonlands — a story common across the West, from the sagebrush country in the north to the Sonoran and Mojave deserts in the south.

In pockets of the Owyhee, you can still find seas of sagebrush rising like small trees amid a proliferation of native bunch grasses and wildflowers, vital habitat for 350 different species. But every year, the country loses around 1 million acres of sagebrush to wildfires, cattle grazing, invasive grasses and human development.

Where wildfires have burned, much of the sagebrush is gone. Gone, too, are the pockets of dirt providing space for the native vegetation to grow, replaced by invasives like cheatgrass and medusahead — a succulent with green snake-like branches that extend from its base and grow yellow flowers.

The disappearing sprawls of sagebrush in the high desert of Oregon means fewer uninterrupted migratory corridors that animals like pronghorns, elk and mule deer depend on to move between their summer and winter ranges, and less crucial habitat for the species that are only found in it, like the sage grouse. In the Owyhees alone, there are 28 endemic species found nowhere else in the world.

The region has long been viewed as nothing more than a desert, said Reginald Sope, a councilman for the Shoshone-Paiute of the Duck Valley Indian Reservation. That was why the U.S. government put reservations there, he said. But now mining operations are looking to dig lithium and uranium — minerals needed for the renewable energy transition — in the southern edge of the Owyhees, near the Duck Valley Reservation, he said.

“This might be a desolate area to [other] people, but to us that’s home,” Sope said, noting that the Shoshone-Paiute of the Duck Valley Indian Reservation trace their people’s inhabiting the area to the beginning of time.

But protecting the area has grown increasingly difficult over the years, said Buster Gibson, the director of the Fish and Game Department for the Shoshone-Paiute Tribe in northern Nevada, whose homelands are in the Owyhee and support new protections for the area. Every year, off-road vehicles exploring the region cut new roads there, he said, threatening not just the ecological intactness of the landscape, but also the tribe’s historical sites. For years, those sites have been robbed, he said, akin to an “ethnic cleansing of our history.”

“It contains our battlegrounds, our prayer sites, our burial sites,” Gibson said. “There’s a lot of culture and a lot of bloodshed here.”

A monument designation — and the resources that come with it — might help to save what’s left before it’s too late.

‘Southern Utah dipped in chocolate’

For decades, groups have advocated for the protection of the Owyhee Canyonlands. Oregon has broad support for conserving the state’s natural resources, but the state has lagged behind its neighbors in the amount of land it has protected, conserving just 172,600 acres over the past 10 years, according to an analysis by the Center for Western Priorities.

“The rural divide is real,” said Houston, with the Oregon Natural Desert Association. Much of the state’s population and environmentalists are centered in cities far to the West, hundreds miles away from the Owyhee, while the county that holds the greatest portion of the canyonlands has a population of just over 30,000.

That divide has halted previous attempts to protect the area. Not long after a 2015 effort to have the Owyhee Canyonlands designated a national monument, a group of armed right-wing militants occupied the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge — not far from where the monument would be — for 41 days in 2016. Led by Ammon Bundy of the ranching family that helped to kill the previous year’s monument proposal, the group promoted the idea that the federal government is required by the constitution to turn over most federal public land to individual states. The idea of a national monument received strong pushback from local ranchers, who have for decades grazed their cattle on public lands in the area.

“At the end of the day, [this land] belongs to the people of America, and it shouldn’t be just whoever picks up the sword and has control in the White House to be able to designate something unilaterally,” said Elias Eiguren, a local rancher who is the treasurer of the Owyhee Basin Stewardship Coalition, which formed to fight the push to make a national conservation area there. “So our group came together and our message was … ‘no monument without a vote of Congress.’”

Despite the coalition’s opposition to the monument push then, they recognized land management in the Owyhee needed to change. Eiguren has lived his whole life in the Owyhee, and the invasive grasses and wildfires are impossible to ignore, he said, so the coalition began working with the environmental groups. They found common ground with the help of Sen. Ron Wyden, a Democrat from Oregon, who worked with the various interests in the area to craft a proposal everyone could get behind.

It led to a bill proposed in Congress by Wyden and Jeff Merkley, Oregon’s other senator, also a Democrat, which would designate the most intact parts of the canyonlands in Oregon — just over 1 million acres—as wilderness areas and form a group comprised of 18 appointed members who would guide projects relating to the natural resources in the area and their management. It would also convey about 30,000 acres to the Burns Paiute Tribe and establish flexible grazing management of the area aimed to better balance conservation and the needs of ranchers.

But some fear the likelihood of the bill passing is slim given partisan politics in the House of Representatives. That’s led the coalition of environmental groups, tribes, local businesses and towns — many of which were involved in the bill’s crafting — to lobby Biden to designate the area outlined in the proposed legislation as a national monument if the bill cannot pass.

Eiguren said the coalition prefers the legislation — as many of the other groups involved do — and is not supportive of the current monument push because it bypasses Congress. “We’re opposed to a monument,” he said. “But if a monument is imposed on us, we still want an opportunity to be involved in how it is actually applied in the future.”

Presidential use of the Antiquities Acts to conserve landmarks is nothing new. Since the act’s passage in 1906 by President Theodore Roosevelt, all but three Republican presidents have used the act to establish new national monuments. Many have been designated after Election Day before a new president takes office. In total, 17 presidents since 1906 have used the act to designate 163 national monuments.

The use of the act, however, is often controversial. Bears Ears National Monument was created in southern Utah by President Barack Obama before he left office, but it was radically shrunk in 2017 by President Donald Trump, then restored to its original size by Biden in 2021. Last year, after years of advocacy from local tribes, communities and environmentalists hoping to protect the area around the Grand Canyon from increased uranium mining, Biden created the Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni — Ancestral Footprints of the Grand Canyon National Monument — in northern Arizona surrounding Grand Canyon National Park. But lawsuits, including one from Arizona Republicans, seek to reverse the designation.

Proponents of the proposal in Oregon recognize the risk of legal action against the designation of a monument there but are confident they can avoid it.

In terms of conservation for the Owyhee Canyonlands, the bill in Congress or a monument designation would achieve largely the same goals, protecting around 1.2 million acres of land from further development and allowing for current livestock grazing operations to continue. But the monument designation would not be able to transfer land to the Burns Paiute Tribe or enact the flexible grazing plan, leading advocates of the monument designation to call for Congress to pass separate bills focused on just those aspects.

If the Owyhee Canyonlands are designated as a national monument, the average visitor wouldn’t notice the change. And that’s the point, Houston said. It would stay a place where people could get lost in the high desert wilderness. But they would notice if the landscape is not protected, he said, as new mines break ground and the sagebrush habitat vital for so many iconic species of the West disappear.

Perhaps the biggest change the monument would bring is how people view it, said Kindle with the National Wildlife Federation. “Once you’ve said ‘monument,’ the collective soul of the country says this is a special place,” he said. “It changes the mindset.”

To those advocating for the Owyhee’s protection, that change in mindset is vital. Places like the Owyhee Canyonlands aren’t made overnight, Kindle said, and intact landscapes like it are shrinking.

Tim Davis, executive director of Friends of the Owyhee, likens the canyonlands to “southern Utah dipped in chocolate.” The proposal impacts Oregonians, but many of them have never seen its canyons bearing the shapes of animals like frogs or its lush sagebrush-filled ranges. The people who recreate in it largely come from Boise, only a few hours away, and have little say in what happens in Oregon.

For now, the Owyhee Canyonlands remain intact. Flying above them, the only sign of human impact is the occasional herd of cattle or a two-track road. But growth is eating around the region’s edges, and nearly all the land in between remains leasable to developers.

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoPolice enter UCLA anti-war encampment; Arizona repeals Civil War-era abortion ban

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoSome Florida boaters seen on video dumping trash into ocean have been identified, officials say

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoThe White House has a new curator. Donna Hayashi Smith is the first Asian American to hold the post

-

Education1 week ago

Education1 week agoVideo: President Biden Addresses Campus Protests

-

)

) Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoThe Idea of You Movie Review: Anne Hathaway’s honest performance makes the film stand out in a not so formulaic rom-com

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoUN, EU, US urge Georgia to halt ‘foreign agents’ bill as protests grow

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoIn the upcoming European elections, peace and security matter the most

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoArizona Senate repeals near-total 1864 abortion ban in divisive vote