Alaska

Alaska’s Climate-Driven Fisheries Collapse Is Devastating Indigenous Communities

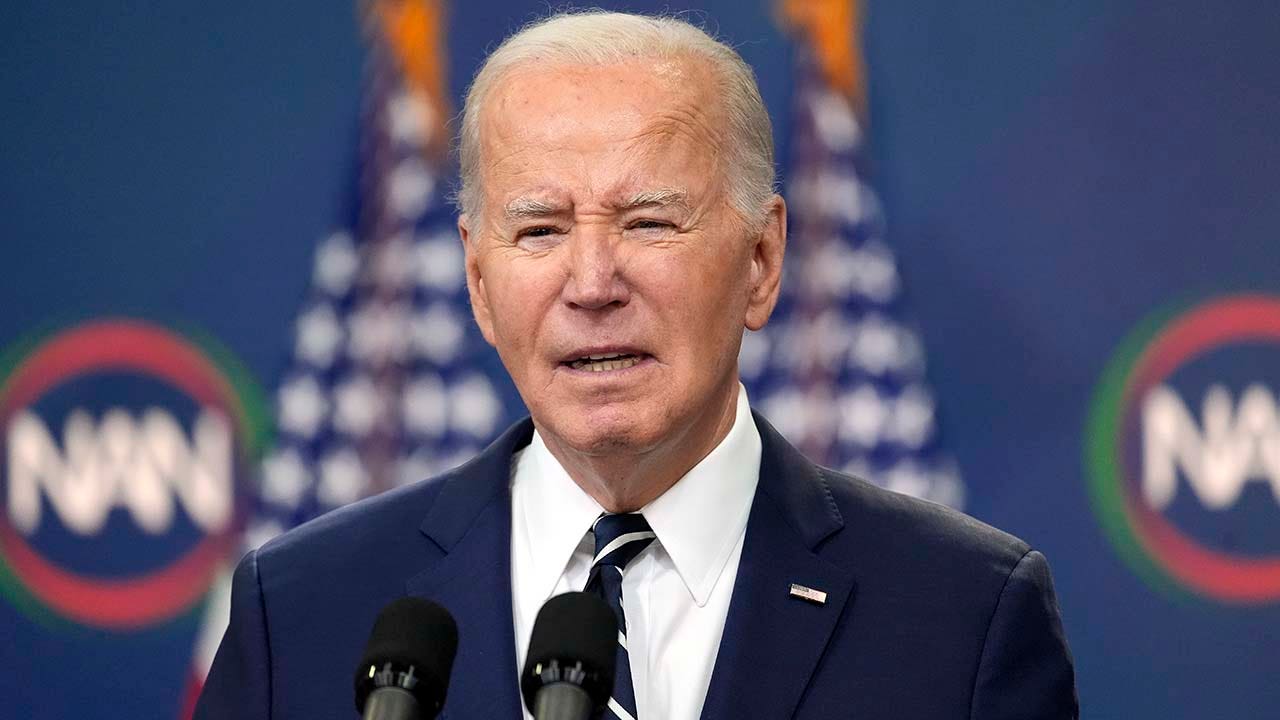

“Fishing is greater than merely having means to fill the pantry with my favourite meals,” says U.S. Consultant Mary Peltola (D-AK), the primary Alaska Native (Yup’ik) in Congress.

Like so many Alaska Natives, Peltola grew up fishing for salmon together with her household for subsistence.

“On the Kuskokwim, infants teethe on dried salmon strips,” she mentioned. “Individuals eat salmon nearly any method you possibly can consider—dried, smoked, jarred, frozen. It’s heartbreaking to witness the crash of salmon populations in river methods we’ve been in a position to depend on so long as I can bear in mind.”

So when king crab, snow crab, and Yukon River salmon fisheries all collapsed final yr, it hit Peltola’s group, and all Indigenous communities in Alaska, arduous. And whereas these climate-related catastrophes might sound a world away from the Decrease 48, they function a harrowing harbinger of what’s to return.

“The complete world is related by oceans, and with extra shoreline than all the opposite states mixed—greater than 46,600 miles—Alaska’s oceans are in some ways America’s oceans,” says Peltola. “Marine ecosystems are the bedrock of our meals provide, whether or not you eat fish or not. However should you do, round 60 p.c of seafood harvested on this nation comes from Alaska’s waters.”

“The complete world is related by oceans, and with extra shoreline than all the opposite states mixed, Alaska’s oceans are in some ways America’s oceans.”

The difficulty began in late 2013, when a large patch of heat ocean water dubbed “the Blob” developed within the Gulf of Alaska, rising sea floor temperatures by as a lot as 7° F. Inside two years, it had enveloped your complete West Coast, stretching greater than 4 million sq. kilometers from Alaska to Mexico earlier than finally splitting into three distinct plenty.

The impacts to Alaska’s fisheries have been colossal. Poisonous algae blooms shaped. Krill populations plummeted, inflicting ripple results for pollock and different fish depending on this meals supply. Gulf of Alaska pink salmon and Pacific cod fisheries collapsed, with cod biomass down 79 p.c from 2013 to 2017. Fish migration patterns modified, with some shifting a whole lot of miles north whereas uncharacteristic warm-water species, like skipjack tuna, moved into Alaskan waters. All of the upheaval is being felt by the state’s residents, who depend on this work and certainly this meals for his or her livelihoods.

However like so many local weather emergencies, the implications have been removed from easy. The place some species suffered, others have thrived. For instance, Bristol Bay sockeye salmon manufacturing has not too long ago hit report highs, serving to hold the state’s fisheries afloat throughout a time of large disruption.

Whereas for local weather scientists and fisheries managers, the continuing results are arduous to foretell—they’re poised to eternally change Alaska’s foodways, industries, and lifestyle.

Disruptions and Their Impacts

Scientists are assured the warming of Alaskan ecosystems will proceed and advise the individuals concerned in Alaskan fisheries—and people consuming their merchandise—to count on many extra disruptions, says Mike Litzow, a program supervisor at NOAA Alaska Fisheries Science Middle and a director at Kodiak Lab.

“Just about any fishery in Alaska ought to take into account itself on discover when it comes to potential vulnerabilities to local weather change,” Litzow mentioned. “The issue is understanding when and the way these impacts are going to play out.”

“Just about any fishery in Alaska ought to take into account itself on discover when it comes to potential vulnerabilities to local weather change.”

The problems transcend simply the Blob and differ drastically throughout Alaska’s 663,300 sq. miles. “The very quickly altering ocean atmosphere, and in flip the thinning and altering seasonality of sea ice, is a giant downside for all of Western and Northern Alaska,” explains Rick Thoman, local weather specialist on the College of Alaska–Fairbanks’ Alaska Middle for Local weather Evaluation and Coverage.

“For mainland Alaska, thawing permafrost goes to trigger main points, significantly associated to infrastructure like roads and buildings,” he continued.

“Then in Southeast Alaska, the warming ocean waters have prolonged the season and prompted the presence of an invasive crab species, which might have a big effect on the marine ecosystem there,” he says. This extremely aggressive predator poses a menace to native species and habitats, in response to NOAA, together with presumably decimating shellfish populations, outcompeting native crabs, and lowering eelgrass and salt marsh habitats.

Alaska

Attorney: $1B suit against Boeing, Alaska Airlines in door plug incident settled out of court

PORTLAND Ore. (KPTV) – Three passengers who sued Boeing and Alaska Airlines for $1 billion over a door plug that flew out mid-air have settled the lawsuit with the companies out of court, according to one of the attorneys for the passengers.

Terms of the settlement were not disclosed, as part of the settlement agreement, according to the attorney.

Court documents show the suit was dismissed with prejudice on July 7, meaning the plaintiffs can not refile the same claim against the companies in the future.

PREVIOUS COVERAGE:

The lawsuit stemmed from an incident on January 5, 2024, when a door plug on Alaska Airlines Flight 1282 from Portland to Ontario, Calif. flew out shortly after takeoff.

Last month, the National Transportation Safety Board found Boeing at fault for the incident following an investigation.

FOX 12 has reached out to Boeing and Alaska Airlines for comment.

Copyright 2025 KPTV-KPDX. All rights reserved.

Alaska

If a tree falls in the forest and no one is around, does it make a buck?

ANCHORAGE, Alaska (KTUU) – The Trump Administration’s announcement to rescind the National Forest’s ‘Roadless Rule’ in June has sparked outrage from some, and support from others. With the two largest National forests in the country, the announcement has caught the attention of Alaska businesses.

The rule, adopted in 2001, essentially prevents new roads from being built in a little over 58 million acres of National Forest, including the Tongass and Chugach National forests in Alaska. In an area that relies heavily on tourism, some fear its natural beauty could be compromised.

“Those magical places could become few and far between, and that’s a major problem,” said Hunter McIntosh, president of the Boat Company, a southeast Alaska non-profit that gives boat tours throughout the region.

Fewer roads means less timber harvest, and that reason, alongside wildfire prevention and others, was given by Secretary of Agriculture Brooke Rollins, who announced the USDA would be rescinding the Roadless Rule last month.

Greater access to the forests by roads has local environmental advocates and business owners like McIntosh concerned that logging and mining interests will be renewed.

“All these things potentially have a significant environmental impact on the fisheries and the wildlife, the hunting, subsistence and whatnot,” McIntosh said. “But then along with that also major impact on the largest economic driver of Southeast Alaska being tourism.”

Not only does McIntosh believe rescinding the rule will damage the environment, but he believes that the timber industry in Southeast Alaska is not economically feasible.

“The economics and what we do are really intertwined, in that — the timber industry is a heavily subsidized industry — and the tourism industry is not subsidized at all,” McIntosh said.

According to a report by the Southeast Conference, timber made up 4% of jobs and employment earnings in 2024.

For those who rely on timber for income, like Viking Lumber Mill in Klawock on Prince of Wales Island, they’d like to see growth in the industry. While the repeal of the roadless rule is a “step forward,” they say the forest service needs to better meet market demand.

“What the timber industry needs in order to survive is for the Forest Service to provide a continuous and ample supply,” said Sarah Dahlstrom, spokesperson for Viking Lumber.

“It is their obligation to do that. They are the largest landowner, and our industry relies on the largest landowner to supply our mill and all of the other micro mills, or mom-and-pop mills on our island.”

”State land is very limited and so we are relying on the Forest Service and the federal government to put timber sales out and it’s been a major struggle.”

Viking Lumber is Alaska’s largest mill, and nearly all of the finished lumber gets shipped to the Lower 48, or internationally.

Dahlstrom’s father, Kirk, bought the bankrupt mill in 1994, returning it to a profitable operation, but says they’re not quite out of the woods yet.

“For decades the Forest Service has failed to provide a sufficient timber supply to the entire industry,” Dahlstrom said.

Dahlstrom said that Viking is largely open because of a legislated land exchange between the Alaska Mental Health Trust and the U.S. Forest Service. For about a decade, the Forest Service has harvested off the land they received, but Dahlstrom said their sale agreement with them will be complete by August of this year.

In a local economy that Dahlstrom said benefits from roads built for timber harvest and wood by-products used to heat schools and public buildings, they hope to stay in business.

“We don’t want to take more than what we need,” Dahlstrom said.

“We want what we’ve been doing. It is a sustainable and renewable business.”

Meanwhile, McIntosh said the Boat Company generally avoids Prince of Wales Island on their tours because of the large swathes of clear-cut forest.

“People from the lower 48, guests and clients, they don’t want to see clear-cut,” McIntosh said. “They want to see wilderness. They want to see, you know, old growth trees. They want to be able to fish for salmon. They want to see bears and whales, and seeing huge swaths of sides of mountains completely clear-cut and then left is not something that that most tourists expect or want to see.”

See a spelling or grammar error? Report it to web@ktuu.com

Copyright 2025 KTUU. All rights reserved.

Alaska

The last woman in the bar: The 1961 murder of an Anchorage lounge singer

Part of a continuing weekly series on Alaska history by local historian David Reamer. Have a question about Anchorage or Alaska history or an idea for a future article? Go to the form at the bottom of this story.

The small clock on the wall revealed a somber reality of the dark, exhausting hours of the early morning. It was Nov. 20, 1961 and nearly 5 a.m., amid the last ticks of the long day at the Club 210, an Anchorage bar on East Fifth Avenue. There were four people in proper attendance, including bartender and co-owner Robert “Chick” Adams serving lounge singer Rose Dawn. The other two men were armed, eager to relieve the establishment of its cash. Three of those four principal actors survived the ensuing tragedy. Those readers familiar with either recent or distant Alaska history will be unsurprised. It was the woman who died.

Rose Dawn was a stage name, coincidentally also a popular brand of nylons back then. Rosemary Niedzwiecki was born in 1938 in San Diego and grew up there, attending Abraham Lincoln High School. She lived to sing, made it her profession, even at a young age establishing herself as a traveling act in destinations like Las Vegas. Meanwhile, as Anchorage boomed in the 1940s through 1950s, waves of new bars and clubs opened here, each viciously competing with the others for the right to raid local wallets. And one way they attracted business was by importing Lower 48 talent as B-girls, dancers and singers. As of November 1961, Rose Dawn was just 23 years old, a dark-eyed beauty working a standing gig for Leo’s Supper Club at the Forest Park Country Club. Forest Park was a golf course, just west of what is now the Westchester Lagoon, then the Chester Creek mudflats.

Club 210 opened in 1956, the name seemingly a bowling reference, as their address was 224 E. Fifth Ave. Joseph Miljas was an original co-owner. Miljas (1913-1979), also known as Papa Joe, later owned the notorious Spenard Road strip club PJ’s, hence the meaning behind those two letters. “Chick” Adams was born in Kentucky and had been in Anchorage for around a decade as of 1961. The smaller bars and clubs then took much of their personality from their owners, who were frequently the bartenders as well. So, the bar was also called “Chick n’ Joes,” or the place to drink with “Chic.” Consistent spelling was hardly a crucial step in getting drunk.

The fateful morning, Nov. 20, 1961, Dawn was unwinding after another grinding performance, verbally dancing with Adams in that expected pattern of bartender and unloading patron. She may have wondered, aloud or otherwise, about the progression or lack thereof in her career. Anchorage clubs in those days tended to pay well but weren’t the sort of prestige gigs that could advance a singer onwards and upwards. No one outside Alaska cared if you headlined the Buckaroo or Last Chance or even Leo’s Supper Club. Perhaps, just perhaps, that is why Dawn was the last woman in the last bar still open on a crisp, chilly night.

Two young men conspired at a table away from the bar, nursing drunks, both of them edgy and uncertain, eyes drifting about to soak in the details. Gerald Lee Cox and Terrance Wayne Brady were both 22 and residents at the Chinook Hotel. Nearing 5 a.m., the last customer besides themselves and Dawn left, prompting Cox and Brady to huddle around the bar. Cox stood and moved as if toward the restroom, only to turn around suddenly while holding an automatic pistol. “My friend wants to see how well you’ve done tonight,” the robber declared.

Cox guarded Dawn and Adams while Brady ransacked the cash register. It had been a solid night at the bar, producing a $250 score, roughly $2,700 in 2025, not counting the hundreds more in checks left behind. But the robbers wanted more. “You got any dough besides what’s in here?” they asked. Adams retorted, “You think I’d keep all that dough in the register if I had a safe?”

A storage room lay behind the bar, cold and drafty. Cox and Brady escorted Dawn and Adams into the back. They demanded Adams’ keys. “What for,” replied the barkeep. “So, I can lock the joint up when we leave,” replied one of the robbers. “We don’t want anybody to come stumbling in here and find you until we’ve had a chance to get away.” Adams grimaced at a sudden realization. His partner wouldn’t arrive to open the bar until 10, nearly five hours later, which should be enough time to let the criminals slip town. Still, he stared at their faces, willing their features into his memory. If given the chance, he wanted to remember them.

Seeing Dawn shiver, Adams argued, “Give the girl a break and let her have her coat. It gets damn cold back here.” One of the thieves responded ominously: “You’ll never feel it.” Then they struck the bartender over the head with a liquor bottle. He swayed toward the floor, dazed, then lost consciousness.

When Adams woke, he was gnawing on a cord wrapped around his head and pulled through his mouth. One of the bandits was trying to choke him to death. Nonetheless, he could see Dawn sprawled nearby, unmoving. As he struggled, two shots rang out in the small room. One passed through Adams’ neck. The other deflected off his skull and lodged near the junction with the spine. Of course, doctors later figured out all those specific details. As far as the robbers could tell, they’d shot Adams twice in the back of the head to massive crimson effect on the surroundings.

Adams was understandably woozy, in shock from the experience and wounds. Still, he recalled one of them talking, “Let’s get out of here. I got him right in the back of the head that time.” In one moment, they were there, standing over him, and in the next they were gone. Pained and growing cold, Adams scrabbled on the floor, moved himself by will toward a phone. With a heroic effort, he managed a single phone call for help, thereafter sinking back to the floor to await whatever came next. In his shaken daze, he had called the fire department, which dispatched an ambulance and subsequently contacted the police.

For a few minutes, Anchorage was shut down as the police sought to close off avenues of escape. They might not have bothered. Cox and Brady were arrested a few minutes later, just five blocks away from Club 210, albeit without gun or cash. They made for a rather conspicuous pair, two young men walking together around a freezing Anchorage at 5 in the morning right after two young men robbed a bar in the immediate vicinity. The officers on duty accomplished no incredible feat of policing when they put that particular two and two together. Because of fresh snow, it took a few days of searching, but the gun was eventually found tossed down an alley and the cash tucked away on a roof.

Given their age, both men had surprisingly lengthy rap sheets, but Cox in particular was well known to local law enforcement. In March 1960, he was arrested for robbing the Sears Roebuck store in Mountain View. After posting bail, he was arrested again that same day for an unconnected robbery. He faced additional charges after attempting to escape the local federal jail that May. In the summer of 1961, he robbed the Anchorage Transit System bus garage and was out on $10,000 bail at the very time he robbed Club 210.

When the ambulance arrived, Dawn was already dead. She had also been shot twice, once in the leg and again in the back of her head. Adams was alive but in serious condition. Doctors were unsure whether he would survive. A day later, he surprisingly improved and was able to identify Cox and Brady from his hospital bed.

As Adams continued to recover, establishing further clearance between himself and the grave, the outcome for the entire affair was carved deeper into stone. An injured living witness meant certainty, in the courts and for the imprisonment to come. There would be no clever legal maneuvers, no surprises. Cox, at least, understood this reality. At his arraignment, he told the judge, “Could you please appoint me (an attorney) so that I can begin proceedings and get this over with.” The waiting is the hardest part, he surely thought. Time to get on with whatever is next.

Adams indeed appeared at their preliminary hearing, pale but sure as he dramatically pointed out the killers, as if from a movie. After their indictments, Cox and Brady shaved a few visits to the courthouse off their lives and pleaded guilty. Their court-appointed attorneys — Ted Stevens represented Brady — argued for 20-year sentences, but Judge James Fitzgerald ordered life imprisonment without recommendation or parole. Fitzgerald described the murder as a “cruel and brutal killing, done with abandoned heart.”

The entire affair was featured in the April 1962 issue of “Official Detective Stories,” one of many pulpy true crime magazines then popular. “Without the Gun and the Money” appeared alongside other luridly titled articles, such as “Who Would Want to Bomb Congressman Green,” “Maybe Donna Had Too Many Friends,” “Human Bait for the Telephone Wolf,” and “I Want to Watch You Kill Me.”

Detective Earl Hibpshman worked the Club 210 case. An article on his 1974 retirement described the pulpy piece as “overdramatized, the old-timers say, and made Hibpshman and others who worked the case look like Columbo, Mike Hammer, and Sherlock Holmes rolled into one.”

Rose Dawn — Rosemary Niedzwiecki — was buried back in her hometown, at San Diego’s Holy Cross Cemetery. Alaska was her undoing, the end to any further career or fame. Or simply life. Alaska in general and Anchorage specifically are often touted as among the most dangerous places in the country for women, what with the dire rates of violence against women here. There are no trustworthy statistics for Alaska from the time of Rose Dawn’s brief tenure, but there is likewise nothing to suggest that it was a better reality. Again and again, a lesson learned, crime is no recent innovation in Anchorage.

[Trapped: The case of the 1951 Interior Alaska cabin fever murder that was solved and then retried]

[The great snoring assault of 1953 Anchorage and other snoring history]

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoTry to Match These Snarky Quotations to Their Novels and Stories

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoVideo: Trump Compliments President of Liberia on His ‘Beautiful English’

-

Finance1 week ago

Do you really save money on Prime Day?

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoApple’s latest AirPods are already on sale for $99 before Prime Day

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoTexas Flooding Map: See How the Floodwaters Rose Along the Guadalupe River

-

Business1 week ago

Companies keep slashing jobs. How worried should workers be about AI replacing them?

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoVideo: Clashes After Immigration Raid at California Cannabis Farm

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoJournalist who refused to duck during Trump assassination attempt reflects on Butler rally in new book