Science

What the New C.D.C. Guidelines Mean for You

The Facilities for Illness Management and Prevention relaxed a lot of its Covid-19 tips this week, shifting sharply away from a number of of the precautions, together with quarantines and social distancing, which have lengthy outlined the pandemic.

The transfer was prompted by the truth that many Individuals now have some immunity to the coronavirus — by a mix of vaccination and former an infection — and by the provision of vaccines, booster pictures and antiviral medicines that may cut back the chance of extreme illness.

A part of the general public well being company’s aim in issuing the brand new steering was to streamline the suggestions and assist individuals handle their very own danger, officers stated. However the tips are nonetheless complicated and comprise loads of nuance.

Listed below are solutions to some frequent questions on what the rules imply for you.

Do I nonetheless have to face six toes away from strangers?

The C.D.C. has not deserted the concept of social distancing completely — as an alternative, the company suggests maintaining a distance from others as one in all many methods that folks can use to assist cut back their danger.

The previous tips really useful that individuals who weren’t up-to-date on their vaccinations “keep no less than six toes away from different individuals” in indoor public areas.

Now, the company recommends that folks “could need to keep away from crowded areas” or preserve a distance from others so as to reduce their publicity to the virus. This precaution could also be particularly necessary for people who find themselves at excessive danger for extreme Covid-19, the company famous.

Do I nonetheless should put on a face masks?

The final masks tips haven’t modified. The C.D.C. nonetheless recommends that everybody age 2 and older put on a well-fitting masks in public indoor areas when the native Covid-19 group degree is excessive. People who find themselves at excessive danger for extreme illness must also put on a masks when their communities are on the medium degree, in keeping with the rules.

Almost 40 % of counties throughout america are at a excessive group degree, in keeping with the C.D.C.

What ought to I do if I’ve been uncovered to the virus?

As a precautionary measure, the C.D.C. used to advocate that individuals who weren’t up-to-date on their vaccinations and had been in shut contact with somebody with Covid-19 keep residence for no less than 5 days, a apply generally known as quarantining. (Individuals who have been up-to-date on their pictures didn’t must quarantine in the event that they have been asymptomatic, in keeping with the earlier tips.)

The quarantine suggestion has disappeared, one of many greatest adjustments within the new steering.

“Quarantines are kind of a blunt instrument,” stated Jennifer Nuzzo, the director of the Pandemic Heart on the Brown College Faculty of Public Well being. “I do suppose we’ve got to shift in how we take into consideration controlling this virus.”

Now, individuals who have been uncovered to the virus can proceed with their each day routines no matter their vaccination standing, so long as they continue to be asymptomatic. Nonetheless, they need to put on a well-fitting masks for 10 full days, monitor themselves for signs, take additional security measures round susceptible individuals and get examined no less than 5 days after publicity.

In case you use an at-home antigen take a look at, it’s possible you’ll want to check your self repeatedly. To scale back the chance of false unfavourable outcomes, individuals who don’t have any signs ought to take no less than three exams, every 48 hours aside, in keeping with a brand new suggestion from the Meals and Drug Administration. Individuals who do have Covid-19 signs ought to take no less than two exams 48 hours aside.

“Your viral load grows after you get contaminated,” stated Dr. Michael Mina, a former Harvard epidemiologist who’s now the chief science officer for eMed, which sells at-home exams. “It goes up, and that takes time.”

What ought to I do if I take a look at optimistic for the virus?

Isolate at residence for no less than 5 days, and hold your distance from others in your family. This suggestion has not modified.

In case you remained asymptomatic throughout your time in isolation — or in case your signs are bettering and you’ve got been fever-free for no less than a day — you may go away isolation after Day 5, in keeping with the rules.

Beforehand, the C.D.C. really useful that folks with Covid-19 put on a masks for 10 full days. Underneath the brand new tips, individuals can take away their masks sooner in the event that they take a look at unfavourable on two speedy antigen exams, taken no less than 48 hours aside. Others ought to proceed to masks for 10 days.

Individuals who expertise reasonable to extreme sickness, or have compromised immune methods, ought to isolate for no less than 10 days, the company stated.

If signs return after isolation, individuals ought to begin their isolation durations over, in keeping with the brand new tips.

What does this imply for faculties and places of work?

In concept, the brand new tips might free many colleges and companies from among the restrictive measures which were tough to implement, together with navigating a distinct algorithm for vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals. Quarantines have been particularly disruptive and divisive in faculties.

Underneath the brand new tips, youngsters who’ve been in shut contact with somebody who has Covid-19 don’t want to remain residence, and faculties don’t must administer frequent exams so as to hold these youngsters within the classroom, an strategy generally known as “take a look at to remain.” Contact tracing and routine surveillance testing of asymptomatic individuals are not needed in most settings, the C.D.C. stated.

In actuality, the brand new tips could not change a lot at many colleges, which had more and more been transferring away from these measures. Massachusetts, for example, dropped its quarantine necessities for asymptomatic youngsters in Could.

Nonetheless, some districts and officers do take their cues from the federal steering, which might immediate some localities to loosen up their guidelines for the approaching educational 12 months.

“We welcome these tips,” Randi Weingarten, the president of the American Federation of Academics, stated in an announcement on Thursday. “Each educator and each dad or mum begins each faculty 12 months with nice hope, and this 12 months much more so. After two years of uncertainty and disruption, we’d like as regular a 12 months as doable so we will focus like a laser on what youngsters want.”

In an electronic mail to The New York Occasions on Friday, the New York State Division of Well being stated it was reviewing the brand new C.D.C. suggestions and would challenge its personal back-to-school steering “quickly.”

New York Metropolis’s Division of Well being and Psychological Hygiene stated on Friday that it was additionally reviewing the brand new federal tips and nonetheless finalizing plans for the approaching faculty 12 months.

The C.D.C.’s tips stated faculties which can be experiencing outbreaks could need to briefly undertake further precautions, together with surveillance testing, contact tracing, mask-wearing and open home windows and doorways to enhance air flow.

Science

Life expectancy in California still hasn't rebounded since the pandemic

During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the virus caused life expectancy in California to drop significantly.

It’s now been over two years since officials declared the pandemic-related public health emergency to be over. And yet, life expectancy for Californians has not fully recovered.

Today, however, the virus has been replaced by drug overdoses and cardiovascular disease as the main causes driving down average lifespans.

A new study published in the medical journal JAMA by researchers from UCLA, Northwestern, Princeton and Virginia Commonwealth University finds that the average life expectancy for Californians in 2024 was nearly a year less than in 2019. The shortfall of 0.86 year signals that only about two-thirds of the state’s pandemic-era losses of 2.92 years have been reversed.

Using mortality data from the California Comprehensive Death Files and population estimates from the American Community Survey, the researchers calculated annual life expectancy from 2019 to 2024, breaking the figures down by race, ethnicity, income and cause of death.

Although the COVID-19 virus was the primary factor in life expectancy declines during the pandemic’s peak, accounting for 61.6% of the life expectancy gap, its impact has significantly lessened. In 2024, COVID-19 accounted for only 12.8% of the life expectancy gap compared with 2019, while drug overdoses and cardiovascular disease contributed more — 19.8% and 16.3%, respectively.

For Black and Hispanic Californians, recovery has been even slower. Life expectancy for Black residents in 2024 remained 1.48 years below 2019 levels, while for Hispanic residents it was 1.44 years lower. In contrast, the gap for white residents was 0.63 year, and for Asian residents, who have the highest life expectancy in the state at 85.51 years, it was 1.06 years. Overall, the life expectancy for Black Californians in 2024 was under 73.5 years, more than a dozen years lower than that of Asian Californians.

Janet Currie, a co-author of the study and professor at Princeton University, noted that these disparities are especially striking. “You saw the very big hit that Hispanic people and Black people took during the pandemic,” she said, “but you also see that Black people in particular are still not caught up.” She added that although Hispanic populations saw a faster rebound, they too remain behind.

Income-based disparities in life expectancy persist in stark form. Californians living in the lowest-income census tracts (the bottom quartile) experienced a 0.99-year gap in 2024 compared with 2019, while those in the highest-income quartile had a slightly smaller 0.85-year gap. However, the overall life expectancy difference between these groups, 5.77 years, was nearly identical to the prepandemic gap of 5.63 years, suggesting that income-based health disparities persist even as pandemic impacts recede.

The study highlights drug overdoses as a primary post-pandemic-emergency driver of reduced life expectancy. Black Californians and residents of low-income areas were especially affected. In 2023, drug overdoses contributed nearly a full year (0.99 year) to the life expectancy deficit for Black Californians and over half a year (0.52) for residents of low-income areas.

That said, there are signs that state and national efforts to address the overdose crisis may be yielding early results. The number for Black Californians declined to 0.55 year in 2024 while it declined to 0.26 year for residents in low-income areas; in the same time frame, the statewide number dropped from 0.4 year to 0.17 year.

Currie attributed the initial surge in overdose deaths in part to the pandemic itself; there were disruptions in access to treatment, and many Californians suffered greater isolation. While she welcomed the recent progress, she cautioned that the share of deaths attributable to overdoses remains high and emphasized that this was “one of the real bad consequences of the pandemic.”

Meanwhile, cardiovascular disease is now the leading contributor to life expectancy loss among high-income Californians. In 2024, it accounted for 0.22 year of the gap for the wealthiest quartile, more than COVID-19 did at 0.10 year. The authors note this is consistent with statewide rising rates of obesity, which may be playing a role.

Dr. Tyler Evans, chief medical officer and chief executive of Wellness Equity Alliance as well as the author of the book “Pandemics, Poverty, and Politics: Decoding the Social and Political Drivers of Pandemics from Plague to COVID-19,” emphasized how the pandemic exacerbated long-standing health inequities. “These chronic health inequities were further amplified as the result of the pandemic,” he said. While investments in social determinants of health initially helped mitigate some of the worst outcomes, he added, “the funding dried up,” making recovery harder for communities already at greater risk of poor outcomes.

Evans also pointed to a broader pattern of overlapping health crises that he described as a “syndemic,” a convergence of epidemics such as addiction, chronic disease and poor access to care that interact to worsen outcomes for historically marginalized populations. “Until we invest in that sort of foundation long term, the numbers will continue to decline,” he said. “California should be a leader in health improvement outcomes in the country, not a state that continues to have our survival decline.”

Although the findings are limited to California and based on preliminary 2024 data, the study provides an early glimpse into post-pandemic mortality trends ahead of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s national life expectancy dataset, expected to be published later this year. California, home to one-eighth of the U.S. population, provides valuable insight into how racial, ethnic and socioeconomic disparities continue to shape public health.

Ultimately, the study highlights how although the most visible impacts of COVID-19 may have faded, their ripple effects, compounded by ongoing structural inequities, continue to shape life and death in California. The pandemic may have accelerated long-standing public health challenges, and the recovery, the study makes clear, has been uneven and incomplete.

Currie warned that further cuts to Medicaid and public hospitals could make these gaps even worse. “We know what to do. We just don’t do it,” she said.

Science

Commentary: A candid take on mortality and the power of friendship

They gather several times a week in the parking lot of a Vons supermarket in Mar Vista, and no subject is off-limits. Not even the grim medical prognosis for 70-year-old David Mays, one of the founding members of the coffee klatch.

“It’s one of our major topics of conversation,” said Paul Morgan, 45, a klatch regular.

Mays is a cancer survivor with a full package of maladies, including diabetes, a faltering heart and failing kidneys. But since I met him almost two years ago, he has told me repeatedly that he doesn’t want dialysis treatment, even though it might extend his life.

“I get it, because it’s a lot of hours out of your day,” said Morgan, a schoolteacher who lives nearby. “People think you go in for dialysis for 15 minutes before you go straight to work. But really, it’s a part-time job.”

Steve Lopez

Steve Lopez is a California native who has been a Los Angeles Times columnist since 2001. He has won more than a dozen national journalism awards and is a four-time Pulitzer finalist.

His treatment would require that he visit a dialysis center three times a week, for four hours each time, Mays said.

“For the rest of my life.”

“I don’t think I could do it,” said klatcher Kit Bradley, 70, who lives in a van near the supermarket with his dog, Lea.

I met Mays in October 2023, when he was living in his Chevy Malibu in a downtown garage that was part of the Safe Parking L.A. program. Mays later moved into an apartment in East Hollywood and still lives there, but his health has continued to deteriorate.

“He is Stage 5,” said Dr. Thet Thet Aung, Mays’ nephrologist at Kaiser Permanente West Los Angeles.

David Mays, center, enjoys a morning get-together with Paul Morgan, left, and Kit Bradley in a Vons parking lot in West Los Angeles on June 25, 2025.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

For such patients, Aung said, death can be imminent. She told me she’s had many conversations with Mays about his treatment options, including dialysis in a clinic or self-administered at home. But not everyone does well on dialysis, she added, and when a patient makes an informed choice, “we respect their wishes.”

Mays has a refreshingly healthy attitude about mortality. Multibillion-dollar industries cater to those who want to look younger and live longer, and about 25% of Medicare’s massive outlay is spent on patients in the last year of life, many of whom choose life-extending medical procedures.

Mays, in the time I’ve known him, has been realistic rather than fatalistic. He has told me he doesn’t think bravery, faith or spirituality has anything to do with his desire to let nature take its course.

“It transcends those things,” he said.

He’s at peace with his fate, he explained, because he’s got friends, love and support.

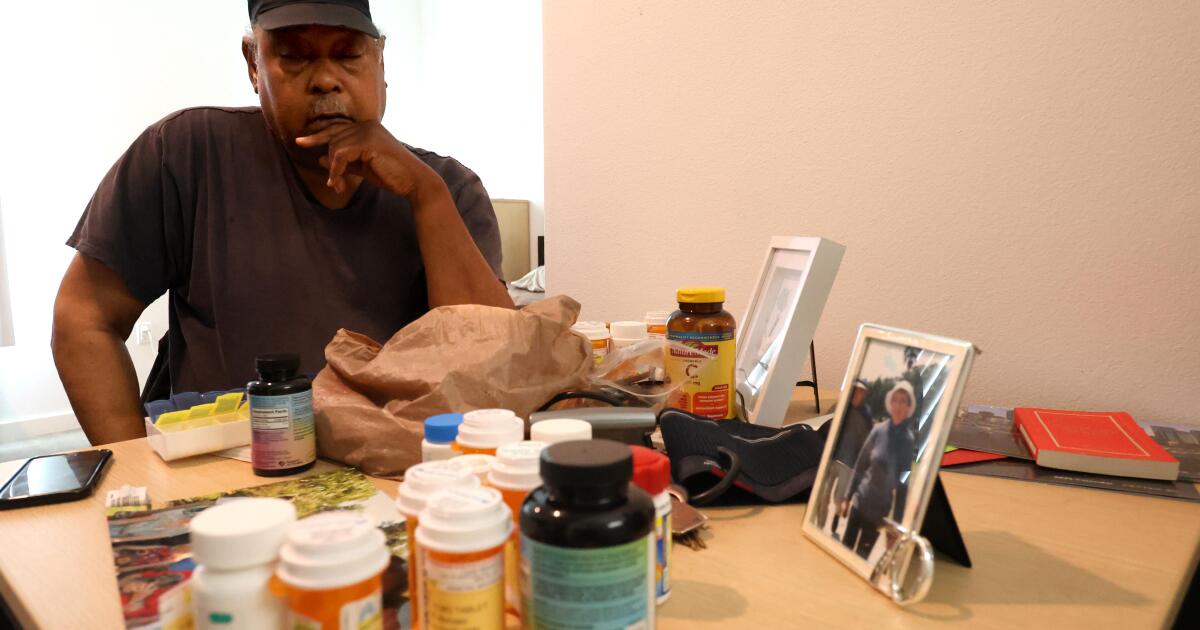

On a recent day at his apartment, I watched Mays load medication from more than 20 vials into a weekly pill organizer.

“I could almost do this in my sleep,” he said as he arranged meds that resembled miniature jelly beans. This one for his kidneys, that one for his heart, his blood pressure, and on and on.

Bottles of medication and photos of close friends rest on David Mays’ table at his apartment in East Hollywood.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

There were 18 pills in each compartment. And none of that will cure any of what ails him, he said.

“You just have to keep doing it, and doing it, just to stay at a sustained level,” he said. “It’s not like … I feel great because I took this stuff.”

Two women in Mays’ life are heartbroken about his condition but respectful of his refusal to try dialysis.

“I don’t want him to suffer for the sake of placating other people,” said Mays’ daughter Jennifer Nutt, 47, of Merced.

Her parents divorced when she and her brother were young, and Nutt had no relationship with Mays until recently. She’s had her own trials, Nutt said, including homelessness.

Father and daughter began connecting in the fall of 2024.

“We spend hours every day talking. It’s like a nonstop festival of catching up,” and they’ve discovered they have the same cheeky sense of humor and pragmatism, and similar traits and interests.

“We like big words and thick books,” Nutt said.

The other woman is Helena Bake, of Perth, Australia, a registered nurse Mays affectionately refers to as “Precious.” They met in 1985, when Mays was visiting London, and Bake, 18 at the time, was working in a restaurant he visited with friends. After Bake moved to Australia, Mays visited her many times and became close to her entire family.

“He was lovely,” said Bake, who is not surprised by Mays’ attitude about his deteriorating health. “He’s always very positive and so pragmatic. He has this wonderful view of the world and the people in his life. It’s such a gift that he has.”

Mays, who gets by on Social Security payments, has set up a GoFundMe page to help pay for his cremation and send his ashes to Bake, to be scattered in his favorite places in Australia.

Lately, medical appointments with his several doctors, and the occasional ER visit, have gotten in the way of one of Mays’ favorite activities — the gatherings in the Vons parking lot.

David Mays is “always very positive and so pragmatic. He has this wonderful view of the world and the people in his life. It’s such a gift that he has,” a longtime friend says.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

Mays worked for many years in the Mar Vista area as a live-in elder care provider, and he’d bump into Bradley at a park, or Morgan in the strip mall that includes the grocery store. Several years ago, they made a habit of grabbing coffee around 7 a.m. and hanging out near Mays’ car. Bradley’s dog often hops into the vehicle, a Vons employee named Elvis comes out for a smoke break, and others come and go.

“I had a cousin who had diabetes, and he called my mom one day and said, ‘I’m not doing it anymore,’ ” Morgan was saying the other day. His mother wasn’t supportive at first, he told the klatch, but she listened to her nephew’s explanation and came around. “Who could judge someone for the choices they make in that situation?”

“There’s a waiting list for kidneys of two to eight years,” Mays said. “Let’s say [in] four or five years, there was a kidney available. Your body can reject it … and then you’re back to the drawing board…. I told Precious about this like a year and a half ago … and she said, ‘I have to hang up now because I have to process this.’ And the next time I talked with her, she said, ‘I get it.’ ”

Mays said he doesn’t want to be “a prisoner to a process, like a machine or something.”

“And you have to do this indefinitely. It’s not like you’re on it for two or three years…,” he said. “It is. The. Rest. Of. Your. Life.”

“I’ve seen people that were on dialysis,” said Bradley, a former musician. “I think I’d rather be just, if I gotta go, I gotta go.”

Morgan said his father, who died last year, had kidney problems in the end and resisted extreme measures to extend his life.

“It’s not like he was at all suicidal, just like David’s not,” Morgan said. “The thing about David is, he’s always been so resolute about it. We’ve never had a discussion where I felt like we could waver him, or like he was on the fence.”

When he first resisted dialysis, Mays said, doctors set him up in a room with a video that explained the process.

“I watched the whole thing, and that was the clincher,” Mays said. “By the time I got through looking at that, I’m just going, ‘Oh HELL no.’”

It’s not that he wants to die, Mays said. It’s that he wants to live on his terms.

“The irony of the whole thing is, it’s all the people that I have around me — they’re the reason I’m willing to go like this. What I get from them in the way of being … uplifted and loved, well, when you have all that, you can deal with anything.”

He has his klatch buddies, he has Precious, he has his daughter in his life again.

“With people around that give a damn about you, care about you, you can deal … with death, you can deal with dying…. And I told my doctors I would rather live a shorter period of time, but with what I feel to be some decent quality of life, than live a longer period of time and be miserable. And I would be miserable on dialysis,” Mays said.

“Plus, I’m 70. It ain’t like I’m 30 and there’s so much life to live. I am the age that I am, and I would like to go further, sure, but it has to close out soon. And I’m fine with that, because I have lived.”

steve.lopez@latimes.com

Science

NIH budget cuts threaten the future of biomedical research — and the young scientists behind it

Over the last several months, a deep sense of unease has settled over laboratories across the United States. Researchers at every stage — from graduate students to senior faculty — have been forced to shelve experiments, rework career plans, and quietly warn each other not to count on long-term funding. Some are even considering leaving the country altogether.

This growing anxiety stems from an abrupt shift in how research is funded — and who, if anyone, will receive support moving forward. As grants are being frozen or rescinded with little warning and layoffs begin to ripple through institutions, scientists have been left to confront a troubling question: Is it still possible to build a future in U.S. science?

On May 2, the White House released its Fiscal Year 2026 Discretionary Budget Request, proposing a nearly $18-billion cut from the National Institutes of Health. This cut, which represents approximately 40% of the NIH’s 2025 budget, is set to take effect on Oct. 1 if adopted by Congress.

“This proposal will have long-term and short-term consequences,” said Stephen Jameson, president of the American Assn. of Immunologists. “Many ongoing research projects will have to stop, clinical trials will have to be halted, and there’ll be the knock-on effects on the trainees who are the next generation of leaders in biomedical research. So I think there’s going to be varied and potentially catastrophic effects, especially on the next generation of our researchers, which in turn will lead to a loss of the status of the U.S. as a leader in biomedical research.“

In the request, the administration justified the move as part of its broader commitment to “restoring accountability, public trust, and transparency at the NIH.” It accused the NIH of engaging in “wasteful spending” and “risky research,” releasing “misleading information,” and promoting “dangerous ideologies that undermine public health.”

National Institutes of Health.

(NIH.gov)

To track the scope of NIH funding cuts, a group of scientists and data analysts launched Grant Watch, an independent project that monitors grant cancellations at the NIH and the National Science Foundation. This database compiles information from public government records, official databases, and direct submissions from affected researchers, grant administrators, and program directors.

As of July 3, Grant Watch reports 4,473 affected NIH grants, totaling more than $10.1 billion in lost or at-risk funding. These include research and training grants, fellowships, infrastructure support, and career development awards — and affect large and small institutions across the country. Research grants were the most heavily affected, accounting for 2,834 of the listed grants, followed by fellowships (473), career development awards (374) and training grants (289).

The NIH plays a foundational role in U.S. research. Its grants support the work of more than 300,000 scientists, technicians and research personnel, across some 2,500 institutions and comprising the vast majority of the nation’s biomedical research workforce. As an example, one study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, found that funding from the NIH contributed to research associated with every one of the 210 new drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration between 2010 and 2016.

Jameson emphasized that these kinds of breakthroughs are made possible only by long-term federal investment in fundamental research. “It’s not just scientists sitting in ivory towers,” he said. “There are enough occasions where [basic research] produces something new and actionable — drugs that will save lives.”

That investment pays off in other ways too. In a 2025 analysis, United for Medical Research, a nonprofit coalition of academic research institutions, patient groups and members of the life sciences industry, found that every dollar the NIH spends generates $2.56 in economic activity.

A ‘brain drain’ on the horizon

Support from the NIH underpins not only research, but also the training pipeline for scientists, physicians and entrepreneurs — the workforce that fuels U.S. leadership in medicine, biotechnology and global health innovation. But continued American preeminence is not a given. Other countries are rapidly expanding their investments in science and research-intensive industries.

If current trends continue, the U.S. risks undergoing a severe “brain drain.” In a March survey conducted by Nature, 75% of U.S. scientists said they were considering looking for jobs abroad, most commonly in Europe and Canada.

This exodus would shrink domestic lab rosters, and could erode the collaborative power and downstream innovation that typically follows discovery. “It’s wonderful that scientists share everything as new discoveries come out,” Jameson said. “But, you tend to work with the people who are nearby. So if there’s a major discovery in another country, they will work with their pharmaceutical companies to develop it, not ours.”

At UCLA, Dr. Antoni Ribas has already started to see the ripple effects. “One of my senior scientists was on the job market,” Ribas said. “She had a couple of offers before the election, and those offers were higher than anything that she’s seen since. What’s being offered to people looking to start their own laboratories and independent research careers is going down — fast.”

In addition, Ribas, who directs the Tumor Immunology Program at the Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center, says that academia and industry are now closing their door to young talent. “The cuts in academia will lead to less positions being offered,” Ribas explained. “Institutions are becoming more reluctant to attract new faculty and provide startup packages.” At the same time, he said, the biotech industry is also struggling. “Even companies that were doing well are facing difficulties raising enough money to keep going, so we’re losing even more potential positions for researchers that are finishing their training.”

This comes at a particularly bitter moment. Scientific capabilities are soaring, with new tools allowing researchers to examine single cells in precise detail, probe every gene in the genome, and even trace diseases at the molecular level. “It’s a pity,” Ribas said, “Because we have made demonstrable progress in treating cancer and other diseases. But now we’re seeing this artificial attack being imposed on the whole enterprise.”

Without federal support, he warns, the system begins to collapse. “It’s as if you have a football team, but then you don’t have a football field. We have the people and the ideas, but without the infrastructure — the labs, the funding, the institutional support — we can’t do the research.”

For graduate students and postdoctoral fellows in particular, funding uncertainty has placed them in a precarious position.

“I think everyone is in this constant state of uncertainty,” said Julia Falo, a postdoctoral fellow at UC Berkeley and recording secretary of UAW 4811, the union for workers at the University of California. “We don’t know if our own grants are going to be funded, if our supervisor’s grants are going to be funded, or even if there will be faculty jobs in the next two years.”

She described colleagues who have had funding delayed or withdrawn without warning, sometimes for containing flagged words like “diverse” or “trans-” or even for having any international component.

The stakes are especially high for researchers on visas. As Falo points out for those researchers, “If the grant that is funding your work doesn’t exist anymore, you can be issued a layoff. Depending on your visa, you may have only a few months to find a new job — or leave the country.”

A graduate student at a California university, who requested anonymity due to the potential impact on their own position — which is funded by an NIH grant— echoed those concerns. “I think we’re all a little on edge. We’re all nervous,” they said. “We have to make sure that we’re planning only a year in advance, just so that we can be sure that we’re confident of where that funding is going to come from. In case it all of a sudden gets cut.”

The student said their decision to pursue research was rooted in a desire to study rare diseases often overlooked by industry. After transitioning from a more clinical setting, they were drawn to academia for its ability to fund smaller, higher-impact projects — the kind that might never turn a profit but could still change lives. They hope to one day become a principal investigator, or PI, and lead their own research lab.

Now, that path feels increasingly uncertain. “If things continue the way that they have been,” they said. “I’m concerned about getting or continuing to get NIH funding, especially as a new PI.”

Still, they are staying committed to academic research. “If we all shy off and back down, the people who want this defunded win.”

Rallying behind science

Already, researchers, universities and advocacy groups have been pushing back against the proposed budget cut.

On campuses across the country, students and researchers have organized rallies, marches and letter-writing campaigns to defend federal research funding. “Stand Up for Science” protests have occurred nationwide, and unions like UAW 4811 have mobilized across the UC system to pressure lawmakers and demand support for at-risk researchers. Their efforts have helped prevent additional state-level cuts in California: in June, the Legislature rejected Gov. Gavin Newsom’s proposed $129.7-million reduction to the UC budget.

Earlier this year, a coalition of public health groups, researchers and unions — led by the American Public Health Assn. — sued the NIH and Department of Health and Human Services over the termination of more than a thousand grants. On June 16, U.S. District Judge William Young ruled in their favor, ordering the NIH to reinstate over 900 canceled grants and calling the terminations unlawful and discriminatory. Although the ruling applies only to grants named in the lawsuit, it marks the first major legal setback to the administration’s research funding rollback.

Though much of the current spotlight (including that lawsuit) has focused on biomedical science, the proposed NIH cuts threaten research far beyond immunology or cancer. Fields ranging from mental health to environmental science stand to lose crucial support. And although some grants may be in the process of reinstatement, the damage already done — paused projects, lost jobs and upended career paths — can’t simply be undone with next year’s budget.

And yet, amid the fear and frustration, there’s still resolve. “I’m floored by the fact that the trainees are still devoted,” Jameson said. “They still come in and work hard. They’re still hopeful about the future.”

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoSee How Trump’s Big Bill Could Affect Your Taxes, Health Care and Other Finances

-

Culture7 days ago

Culture7 days ago16 Mayors on What It’s Like to Run a U.S. City Now Under Trump

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoVideo: Who Loses in the Republican Policy Bill?

-

Science7 days ago

Science7 days agoFederal contractors improperly dumped wildfire-related asbestos waste at L.A. area landfills

-

Politics5 days ago

Politics5 days agoVideo: Trump Signs the ‘One Big Beautiful Bill’ Into Law

-

Politics7 days ago

Politics7 days agoCongressman's last day in office revealed after vote on Trump's 'Big, Beautiful Bill'

-

World5 days ago

World5 days agoRussia-Ukraine war: List of key events, day 1,227

-

Technology7 days ago

Technology7 days agoMeet Soham Parekh, the engineer burning through tech by working at three to four startups simultaneously