Science

Can Omicron overtake the Delta variant? Here’s what it will take

With a handful of circumstances now confirmed throughout the nation, it’s clear that the Omicron variant has established a toehold in the US.

However whether or not these preliminary infections fade out or develop into the beachhead for a brand new viral assault relies upon largely on how Omicron stacks up towards a now-familiar foe: the Delta variant.

Because it burst onto the scene final week, scientists have been working to determine whether or not its quite a few mutations assist it unfold extra simply than its predecessors, make its victims sicker, or scale back the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines and medicines.

But there’s one other query that’s simply as vital for forecasting Omicron’s impact on the pandemic: What if it’s no match for the satan we all know?

Publication

Get our free Coronavirus Immediately e-newsletter

Join the newest information, finest tales and what they imply for you, plus solutions to your questions.

It’s possible you’ll often obtain promotional content material from the Los Angeles Occasions.

“Can Delta outcompete Omicron, or will Omicron thrive within the face of Delta?” mentioned John Moore, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Weill Cornell Medical Faculty. “That’s only a full unknown for the time being.”

The Delta variant has lengthy been the dominant pressure within the U.S. — and it was the offender behind a renewed wave of circumstances, hospitalizations and deaths that swept the nation over the summer season.

“Dominant” undersells simply how widespread Delta is. In the US, it’s almost omnipresent.

“I do know that the information is targeted on Omicron, however we should always do not forget that 99.9% of circumstances within the nation proper now are from the Delta variant,” mentioned Dr. Rochelle Walensky, director of the U.S. Facilities for Illness Management and Prevention. “Delta continues to drive circumstances throughout the nation, particularly in those that are unvaccinated.”

The explanation for the pressure’s supremacy is easy: It’s twice as transmissible as the unique SARS-CoV-2 virus. Consequently, it’s been capable of elbow apart different variants that in any other case might need unfold extra broadly.

Look no additional than the Beta variant, which scientists thought-about a possible risk as a result of it seemed prefer it would possibly imperil the efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines.

“By no means occurred,” Moore mentioned. “Beta was squelched out by Delta. Nicely, that might occur to Omicron.”

In Africa, Omicron has been linked to a steep rise in new infections, suggesting it’s certainly extremely transmissible. However it might have confronted much less daunting competitors in Africa than it should in the US.

The Alpha and Beta variants proceed to flow into broadly in Africa, accounting for nearly half of recent infections examined there. It’s doable that Omicron can outcompete them however will likely be stymied by Delta.

That’s not completely excellent news. Delta has proved greater than able to chopping a devastating swath by the U.S.

Even with out factoring in Omicron, “we already are going through a Delta-driven winter surge that’s going to kill one other 100,000 to 150,000 People,” Moore mentioned.

Omicron’s rise in South Africa got here at a time when new infections have been comparatively low, a context that might result in overestimates of its transmissibility. As scientists stepped up their assortment of viral samples round an outbreak, they might have captured a excessive price of unfold that was distinctive to that cluster however received’t reoccur in a broad inhabitants.

There have been early indicators that Omicron is extra able to reinfecting individuals who have recovered from earlier coronavirus infections.

“Not a large impact. However it’s statistically vital,” Moore mentioned, based mostly on preliminary analyses he’s reviewed. “And that might be according to the extremely mutated nature of Omicron.”

A brand new risk evaluation from the UK’s Well being Safety Company says that fashions developed by scientists at Oxford College counsel Omicron might replicate extra rapidly within the physique by binding extra tightly to the ACE2 receptor on human cells. That binding affinity seems to occur “to a a lot higher extent than that seen for another variant,” the report states.

Scientists have lengthy argued that in a virus’ never-ending quest to contaminate new hosts, genetic mutations that improve transmissibility will finest guarantee its survival. New variants give the coronavirus recent alternatives to unfold and safe its future, mentioned Wesleyan College microbiologist Frederick Cohan.

There are lots of methods to try this, and the virus must hit on the proper change to enhance its prospects, Cohan mentioned. It might make itself extra transmissible by hovering longer in or touring extra readily by the air. It might maintain contaminated individuals contagious for longer. It might trigger milder sickness, retaining spreaders in vast circulation.

Widespread vaccination slows transmission by making the virus work more durable to search out its subsequent sufferer. But when Omicron — or another variant — finds a solution to overcome the safety provided by vaccines, the reward will likely be an even bigger pool of potential hosts.

In a way, a vaccine-resistant variant would regain the target-rich setting the unique pressure loved firstly of the pandemic, mentioned Dr. Jonathan Schiffer, an infectious-diseases knowledgeable on the Fred Hutchinson Most cancers Analysis Middle in Seattle.

“The virus which may win now isn’t essentially the identical variant that received up to now,” Schiffer mentioned.

Nonetheless unknown is whether or not individuals sickened by Omicron are roughly prone to develop into severely ailing than individuals sickened by Delta.

The chair of the South African Medical Assn. mentioned in a newspaper op-ed this week that “nobody right here in South Africa is thought to have been hospitalized with the Omicron variant.”

That’s heartening, however officers say it’s nonetheless too early to know whether or not Omicron will make individuals extra sick than Delta does. It’s doable that Omicron has treaded extra frivolously on its victims in South Africa as a result of it has contaminated youthful, in any other case wholesome individuals who aren’t notably prone to develop into severely ailing with COVID-19. If the brand new variant encounters a extra weak inhabitants, the image might change, Moore mentioned.

“Normally, it takes time for a extreme sickness to essentially require hospitalization,” mentioned Dr. Regina Chinsio-Kwong, an Orange County deputy well being officer. “So we’ll discover out, most likely in one other two weeks, how extreme Omicron may be on the system.”

Science

How a Supreme Court win for public health bolstered RFK Jr. and threatens no-cost vaccines

WASHINGTON — Public health advocates won a big case in the Supreme Court on the last day of this year’s term, but the victory came with an asterisk.

The decision ended one threat to the no-cost preventive services — from cancer and diabetes screenings to statin drugs and vaccines — used by more than 150 million Americans who have health insurance.

But it did so by empowering the nation’s foremost vaccine skeptic: Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

Losing would have been “a terrible result,” said Washington attorney Andrew Pincus. Insurers would have been free to quit paying for the drugs, screenings and other services that were proven effective in saving lives and money.

But winning means that “the secretary has the power to set aside” the recommendations of medical experts and remove approved drugs, he said. “His actions will be subject to review in court,” he added.

The new legal fight has already begun.

Last month, Kennedy cited a “crisis of public trust” when he removed all 17 members of a separate vaccine advisory committee. His replacements included some vaccine skeptics.

The vaccines that are recommended by this committee are included as preventive services that insurers must provide.

On Monday, the American Academy of Pediatrics and other medical groups sued Kennedy for having removed the COVID-19 vaccine as a recommended immunization for pregnant women and healthy children. The suit called this an “arbitrary” and “baseless” decision that violates the Administrative Procedure Act.

“We’re taking legal action because we believe children deserve better,” said Dr. Susan J. Kressly, the academy’s president. “This wasn’t just sidelining science. It’s an attack on the very foundation of how we protect families and children’s health.”

On Wednesday, Kennedy postponed a scheduled meeting of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force that was at the center of the court case.

“Obviously, many screenings that relate to chronic diseases could face changes,” said Richard Hughes IV, a Washington lawyer and law professor. “A major area of concern is coverage of PrEP for HIV,” a preventive drug that was challenged in the Texas lawsuit that came to the Supreme Court.

By one measure, the Supreme Court’s 6-3 decision was a rare win for liberals. The justices overturned a ruling by Texas judges that would have struck down the popular benefit that came with Obamacare. The 2012 law required insurers to provide at no cost the preventive services that were approved as highly effective.

But conservative critics had spotted what they saw was a flaw in the Affordable Care Act. They noted the task force of unpaid medical experts who recommend the best and most cost-effective preventive care was described in the law as “independent.”

That word was enough to drive the five-year legal battle.

Steven Hotze, a Texas employer, had sued in 2020 and said he objected on religious grounds to providing HIV prevention drugs, even if none of his employees were using those drugs.

The suit went before U.S. District Judge Reed O’Connor in Fort Worth, who in 2018 had struck down Obamacare as unconstitutional. In 2022, he ruled for the Texas employer and struck down the required preventive services on the grounds that members of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force made legally binding decisions even though they had not been appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate.

The 5th Circuit Court put his decision on hold but upheld his ruling that the work of the preventive services task force was unconstitutional because its members were “free from any supervision” by the president.

Last year, the Biden administration asked the Supreme Court to hear the case of Xavier Becerra vs. Braidwood Management. The appeal said the Texas ruling “jeopardizes health protections that have been in place for 14 years and millions of Americans currently enjoy.”

The court agreed to hear the case, and by the time of the oral argument in April, the Trump administration had a new secretary of HHS. The case was now Robert F. Kennedy Jr. vs. Braidwood Management.

The court’s six conservatives believe the Constitution gives the president full executive power to control the government and to put his officials in charge. But they split on what that meant in this case.

The Constitution says the president can appoint ambassadors, judges and “all other Officers of the United States” with Senate approval. In addition, “Congress may by law vest the appointment of such inferior officers” in the hands of the president or “the heads of departments.”

Option two made more sense, said Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh. He spoke for the court, including Chief Justice John G. Roberts and Justice Amy Coney Barrett, and the court’s three liberal justices.

“The Executive Branch under both President Trump and President Biden has argued that the Preventive Services Task Force members are inferior officers and therefore may be appointed by the Secretary of HHS. We agree,” he wrote.

This “preserves the chain of political accountability. … The Task Force members are removable at will by the Secretary of HHS, and their recommendations are reviewable by the Secretary before they take effect.”

The ruling was a clear win for Kennedy and the Trump administration. It made clear the medical experts are not “independent” and can be readily replaced by RFK Jr.

It did not win over the three justices on the right. Justice Clarence Thomas wrote a 37-page dissent.

“Under our Constitution, appointment by the President with Senate confirmation is the rule. Appointment by a department head is an exception that Congress must consciously choose to adopt,” he said, joined by Justices Samuel A. Alito and Neil M. Gorsuch.

Science

Life expectancy in California still hasn't rebounded since the pandemic

During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the virus caused life expectancy in California to drop significantly.

It’s now been over two years since officials declared the pandemic-related public health emergency to be over. And yet, life expectancy for Californians has not fully recovered.

Today, however, the virus has been replaced by drug overdoses and cardiovascular disease as the main causes driving down average lifespans.

A new study published in the medical journal JAMA by researchers from UCLA, Northwestern, Princeton and Virginia Commonwealth University finds that the average life expectancy for Californians in 2024 was nearly a year less than in 2019. The shortfall of 0.86 year signals that only about two-thirds of the state’s pandemic-era losses of 2.92 years have been reversed.

Using mortality data from the California Comprehensive Death Files and population estimates from the American Community Survey, the researchers calculated annual life expectancy from 2019 to 2024, breaking the figures down by race, ethnicity, income and cause of death.

Although the COVID-19 virus was the primary factor in life expectancy declines during the pandemic’s peak, accounting for 61.6% of the life expectancy gap, its impact has significantly lessened. In 2024, COVID-19 accounted for only 12.8% of the life expectancy gap compared with 2019, while drug overdoses and cardiovascular disease contributed more — 19.8% and 16.3%, respectively.

For Black and Hispanic Californians, recovery has been even slower. Life expectancy for Black residents in 2024 remained 1.48 years below 2019 levels, while for Hispanic residents it was 1.44 years lower. In contrast, the gap for white residents was 0.63 year, and for Asian residents, who have the highest life expectancy in the state at 85.51 years, it was 1.06 years. Overall, the life expectancy for Black Californians in 2024 was under 73.5 years, more than a dozen years lower than that of Asian Californians.

Janet Currie, a co-author of the study and professor at Princeton University, noted that these disparities are especially striking. “You saw the very big hit that Hispanic people and Black people took during the pandemic,” she said, “but you also see that Black people in particular are still not caught up.” She added that although Hispanic populations saw a faster rebound, they too remain behind.

Income-based disparities in life expectancy persist in stark form. Californians living in the lowest-income census tracts (the bottom quartile) experienced a 0.99-year gap in 2024 compared with 2019, while those in the highest-income quartile had a slightly smaller 0.85-year gap. However, the overall life expectancy difference between these groups, 5.77 years, was nearly identical to the prepandemic gap of 5.63 years, suggesting that income-based health disparities persist even as pandemic impacts recede.

The study highlights drug overdoses as a primary post-pandemic-emergency driver of reduced life expectancy. Black Californians and residents of low-income areas were especially affected. In 2023, drug overdoses contributed nearly a full year (0.99 year) to the life expectancy deficit for Black Californians and over half a year (0.52) for residents of low-income areas.

That said, there are signs that state and national efforts to address the overdose crisis may be yielding early results. The number for Black Californians declined to 0.55 year in 2024 while it declined to 0.26 year for residents in low-income areas; in the same time frame, the statewide number dropped from 0.4 year to 0.17 year.

Currie attributed the initial surge in overdose deaths in part to the pandemic itself; there were disruptions in access to treatment, and many Californians suffered greater isolation. While she welcomed the recent progress, she cautioned that the share of deaths attributable to overdoses remains high and emphasized that this was “one of the real bad consequences of the pandemic.”

Meanwhile, cardiovascular disease is now the leading contributor to life expectancy loss among high-income Californians. In 2024, it accounted for 0.22 year of the gap for the wealthiest quartile, more than COVID-19 did at 0.10 year. The authors note this is consistent with statewide rising rates of obesity, which may be playing a role.

Dr. Tyler Evans, chief medical officer and chief executive of Wellness Equity Alliance as well as the author of the book “Pandemics, Poverty, and Politics: Decoding the Social and Political Drivers of Pandemics from Plague to COVID-19,” emphasized how the pandemic exacerbated long-standing health inequities. “These chronic health inequities were further amplified as the result of the pandemic,” he said. While investments in social determinants of health initially helped mitigate some of the worst outcomes, he added, “the funding dried up,” making recovery harder for communities already at greater risk of poor outcomes.

Evans also pointed to a broader pattern of overlapping health crises that he described as a “syndemic,” a convergence of epidemics such as addiction, chronic disease and poor access to care that interact to worsen outcomes for historically marginalized populations. “Until we invest in that sort of foundation long term, the numbers will continue to decline,” he said. “California should be a leader in health improvement outcomes in the country, not a state that continues to have our survival decline.”

Although the findings are limited to California and based on preliminary 2024 data, the study provides an early glimpse into post-pandemic mortality trends ahead of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s national life expectancy dataset, expected to be published later this year. California, home to one-eighth of the U.S. population, provides valuable insight into how racial, ethnic and socioeconomic disparities continue to shape public health.

Ultimately, the study highlights how although the most visible impacts of COVID-19 may have faded, their ripple effects, compounded by ongoing structural inequities, continue to shape life and death in California. The pandemic may have accelerated long-standing public health challenges, and the recovery, the study makes clear, has been uneven and incomplete.

Currie warned that further cuts to Medicaid and public hospitals could make these gaps even worse. “We know what to do. We just don’t do it,” she said.

Science

Commentary: A candid take on mortality and the power of friendship

They gather several times a week in the parking lot of a Vons supermarket in Mar Vista, and no subject is off-limits. Not even the grim medical prognosis for 70-year-old David Mays, one of the founding members of the coffee klatch.

“It’s one of our major topics of conversation,” said Paul Morgan, 45, a klatch regular.

Mays is a cancer survivor with a full package of maladies, including diabetes, a faltering heart and failing kidneys. But since I met him almost two years ago, he has told me repeatedly that he doesn’t want dialysis treatment, even though it might extend his life.

“I get it, because it’s a lot of hours out of your day,” said Morgan, a schoolteacher who lives nearby. “People think you go in for dialysis for 15 minutes before you go straight to work. But really, it’s a part-time job.”

Steve Lopez

Steve Lopez is a California native who has been a Los Angeles Times columnist since 2001. He has won more than a dozen national journalism awards and is a four-time Pulitzer finalist.

His treatment would require that he visit a dialysis center three times a week, for four hours each time, Mays said.

“For the rest of my life.”

“I don’t think I could do it,” said klatcher Kit Bradley, 70, who lives in a van near the supermarket with his dog, Lea.

I met Mays in October 2023, when he was living in his Chevy Malibu in a downtown garage that was part of the Safe Parking L.A. program. Mays later moved into an apartment in East Hollywood and still lives there, but his health has continued to deteriorate.

“He is Stage 5,” said Dr. Thet Thet Aung, Mays’ nephrologist at Kaiser Permanente West Los Angeles.

David Mays, center, enjoys a morning get-together with Paul Morgan, left, and Kit Bradley in a Vons parking lot in West Los Angeles on June 25, 2025.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

For such patients, Aung said, death can be imminent. She told me she’s had many conversations with Mays about his treatment options, including dialysis in a clinic or self-administered at home. But not everyone does well on dialysis, she added, and when a patient makes an informed choice, “we respect their wishes.”

Mays has a refreshingly healthy attitude about mortality. Multibillion-dollar industries cater to those who want to look younger and live longer, and about 25% of Medicare’s massive outlay is spent on patients in the last year of life, many of whom choose life-extending medical procedures.

Mays, in the time I’ve known him, has been realistic rather than fatalistic. He has told me he doesn’t think bravery, faith or spirituality has anything to do with his desire to let nature take its course.

“It transcends those things,” he said.

He’s at peace with his fate, he explained, because he’s got friends, love and support.

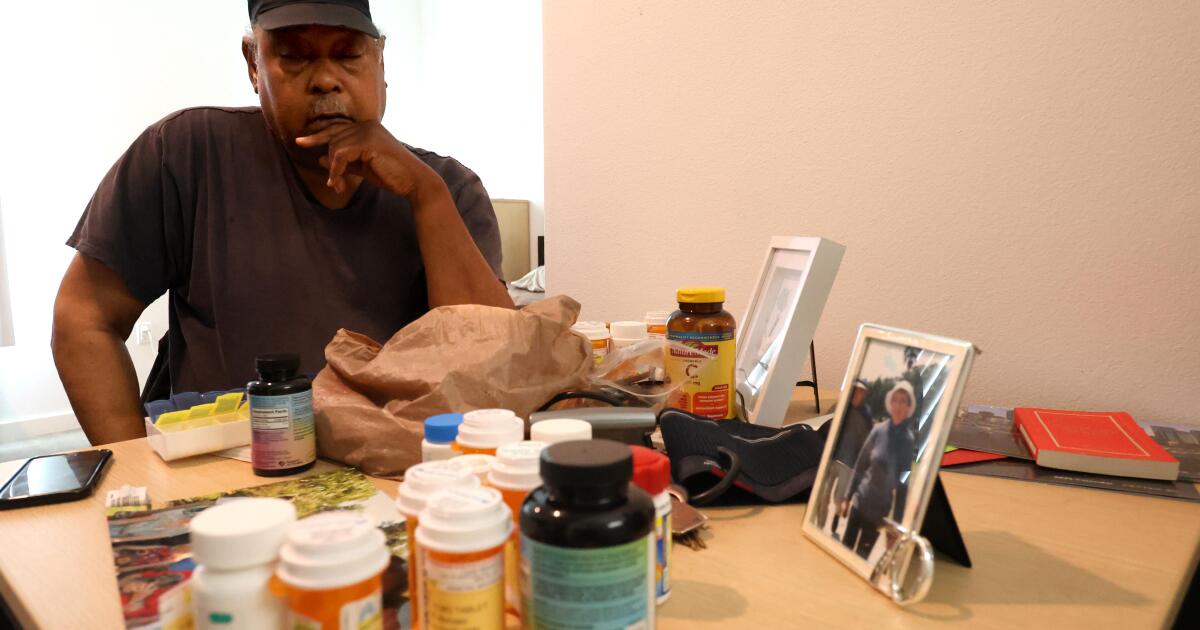

On a recent day at his apartment, I watched Mays load medication from more than 20 vials into a weekly pill organizer.

“I could almost do this in my sleep,” he said as he arranged meds that resembled miniature jelly beans. This one for his kidneys, that one for his heart, his blood pressure, and on and on.

Bottles of medication and photos of close friends rest on David Mays’ table at his apartment in East Hollywood.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

There were 18 pills in each compartment. And none of that will cure any of what ails him, he said.

“You just have to keep doing it, and doing it, just to stay at a sustained level,” he said. “It’s not like … I feel great because I took this stuff.”

Two women in Mays’ life are heartbroken about his condition but respectful of his refusal to try dialysis.

“I don’t want him to suffer for the sake of placating other people,” said Mays’ daughter Jennifer Nutt, 47, of Merced.

Her parents divorced when she and her brother were young, and Nutt had no relationship with Mays until recently. She’s had her own trials, Nutt said, including homelessness.

Father and daughter began connecting in the fall of 2024.

“We spend hours every day talking. It’s like a nonstop festival of catching up,” and they’ve discovered they have the same cheeky sense of humor and pragmatism, and similar traits and interests.

“We like big words and thick books,” Nutt said.

The other woman is Helena Bake, of Perth, Australia, a registered nurse Mays affectionately refers to as “Precious.” They met in 1985, when Mays was visiting London, and Bake, 18 at the time, was working in a restaurant he visited with friends. After Bake moved to Australia, Mays visited her many times and became close to her entire family.

“He was lovely,” said Bake, who is not surprised by Mays’ attitude about his deteriorating health. “He’s always very positive and so pragmatic. He has this wonderful view of the world and the people in his life. It’s such a gift that he has.”

Mays, who gets by on Social Security payments, has set up a GoFundMe page to help pay for his cremation and send his ashes to Bake, to be scattered in his favorite places in Australia.

Lately, medical appointments with his several doctors, and the occasional ER visit, have gotten in the way of one of Mays’ favorite activities — the gatherings in the Vons parking lot.

David Mays is “always very positive and so pragmatic. He has this wonderful view of the world and the people in his life. It’s such a gift that he has,” a longtime friend says.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

Mays worked for many years in the Mar Vista area as a live-in elder care provider, and he’d bump into Bradley at a park, or Morgan in the strip mall that includes the grocery store. Several years ago, they made a habit of grabbing coffee around 7 a.m. and hanging out near Mays’ car. Bradley’s dog often hops into the vehicle, a Vons employee named Elvis comes out for a smoke break, and others come and go.

“I had a cousin who had diabetes, and he called my mom one day and said, ‘I’m not doing it anymore,’ ” Morgan was saying the other day. His mother wasn’t supportive at first, he told the klatch, but she listened to her nephew’s explanation and came around. “Who could judge someone for the choices they make in that situation?”

“There’s a waiting list for kidneys of two to eight years,” Mays said. “Let’s say [in] four or five years, there was a kidney available. Your body can reject it … and then you’re back to the drawing board…. I told Precious about this like a year and a half ago … and she said, ‘I have to hang up now because I have to process this.’ And the next time I talked with her, she said, ‘I get it.’ ”

Mays said he doesn’t want to be “a prisoner to a process, like a machine or something.”

“And you have to do this indefinitely. It’s not like you’re on it for two or three years…,” he said. “It is. The. Rest. Of. Your. Life.”

“I’ve seen people that were on dialysis,” said Bradley, a former musician. “I think I’d rather be just, if I gotta go, I gotta go.”

Morgan said his father, who died last year, had kidney problems in the end and resisted extreme measures to extend his life.

“It’s not like he was at all suicidal, just like David’s not,” Morgan said. “The thing about David is, he’s always been so resolute about it. We’ve never had a discussion where I felt like we could waver him, or like he was on the fence.”

When he first resisted dialysis, Mays said, doctors set him up in a room with a video that explained the process.

“I watched the whole thing, and that was the clincher,” Mays said. “By the time I got through looking at that, I’m just going, ‘Oh HELL no.’”

It’s not that he wants to die, Mays said. It’s that he wants to live on his terms.

“The irony of the whole thing is, it’s all the people that I have around me — they’re the reason I’m willing to go like this. What I get from them in the way of being … uplifted and loved, well, when you have all that, you can deal with anything.”

He has his klatch buddies, he has Precious, he has his daughter in his life again.

“With people around that give a damn about you, care about you, you can deal … with death, you can deal with dying…. And I told my doctors I would rather live a shorter period of time, but with what I feel to be some decent quality of life, than live a longer period of time and be miserable. And I would be miserable on dialysis,” Mays said.

“Plus, I’m 70. It ain’t like I’m 30 and there’s so much life to live. I am the age that I am, and I would like to go further, sure, but it has to close out soon. And I’m fine with that, because I have lived.”

steve.lopez@latimes.com

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoSee How Trump’s Big Bill Could Affect Your Taxes, Health Care and Other Finances

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week ago16 Mayors on What It’s Like to Run a U.S. City Now Under Trump

-

Politics6 days ago

Politics6 days agoVideo: Trump Signs the ‘One Big Beautiful Bill’ Into Law

-

Science1 week ago

Science1 week agoFederal contractors improperly dumped wildfire-related asbestos waste at L.A. area landfills

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: Who Loses in the Republican Policy Bill?

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoMeet Soham Parekh, the engineer burning through tech by working at three to four startups simultaneously

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoCongressman's last day in office revealed after vote on Trump's 'Big, Beautiful Bill'

-

World7 days ago

World7 days agoRussia-Ukraine war: List of key events, day 1,227