Boston, MA

Jacob Wirth, the Bierhaus That Burned Down. Twice.

Longform

Will the 150-year-old Jacob Wirth collapse under the heat, or can it rise from the ashes once again?

Illustration by Benjamen Purvis / Photo via Wikimedia Commons/Biruitorul

It was a total loss from the start.

On June 24, Boston fire crews rushed over to Jacob Wirth, a restaurant on Stuart Street about a block from the Common. News footage showed red-hot flames shooting toward the sky as geysers of thick black smoke choked the night air, transforming the Theater District landmark, known for its old-school German fare and lively atmosphere, into a scene of destruction.

They arrived just before 11 p.m. to battle the four-alarm blaze engulfing the 180-year-old structure, aiming “big lines” and “blitz guns,” according to the Boston Fire Department report. After firefighters were ordered out of the three-story building due to holes in the floor, multiple fire companies stationed on the upper levels of a next-door parking garage and on the street below beat back the flames in both directions.

More than an hour later, the worst of the blaze was over, but firefighters stayed on the scene until 8 a.m. to extinguish hot spots throughout the building, and Stuart Street remained closed to traffic until the early afternoon. When the fire was finally out, the destruction was almost inconceivable. “The bar was pretty much charred from the top down,” said Jamison LaGuardia, vice president of sales and operations at Royale Entertainment Group, who, along with several others, purchased the restaurant in early 2023. The building’s roof was also destroyed—a social media post from the Boston Fire Department on June 25 showed four gaping holes and cracked tiles on the building’s roof—while inside, water from the sprinklers and fire hoses drenched the floors, which then sat damp and moldy for weeks in the summer heat, LaGuardia said. Early estimates put the damage at some $3 million. Though the fire’s cause remains under investigation, one thing was clear: Jacob Wirth had been destroyed.

Oddly enough, this wasn’t the first devastating fire at the property: Shortly after it was put up for sale in June 2018, the iconic German restaurant had burst into flames. (The cause of that fire was listed as “undetermined,” though human involvement was not suspected.) At the time of the second fire, LaGuardia and the rest of the new ownership team were in the process of readying the restaurant for a comeback. In fact, they say, Jacob Wirth was less than three months from reopening—a general manager had been hired, kitchen equipment had been scheduled for delivery, and a new logo had been designed.

Now, it might not be ready for a number of years. “I don’t want to give the impression that we’ve given up. Quite the opposite,” says Jacob Simmons, the vice president of project management at City Realty, another Jacob Wirth owner. Yet speaking in early fall through a palpable sense of frustration and grief, LaGuardia and Simmons struggled to articulate a path forward. Which begs the question: What will become of this celebrated throwback to a Boston long gone?

The interior, shown in 2018, changed little over the years. / Photo by Jim Davis/the Boston Globe via Getty Images

An immigrant from the Rhineland, Jacob Wirth arrived in the United States during the 1830s and opened a bar on Eliot Street (now Stuart Street) in 1868. After a decade, he moved his business across the street to its current location. The restaurant drew a diverse clientele, including families, and served unpretentious, steam-cooked German favorites—think herring and sauerbraten—without hurting patrons’ wallets, wrote urban planning scholar James O’Connell in his book Dining Out in Boston. In its early years, the restaurant, operated by Wirth’s relatives until 1965 and purchased by the Fitzgerald family in 1975, offered a male-dominated social environment and appealed to Boston beer drinkers as the city’s first Anheuser-Busch distributor.

German restaurants were particularly attractive to diners searching for new flavors, says Andrew Haley, a cultural historian and author of Turning the Tables, which recounts the story of American restaurants in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. “After the Civil War in the late 1860s and 1870s, we were increasingly seeing some interest among the general population in culinary adventurism,” Haley notes. “German restaurants became one of the first places that people ventured out to try something a little exotic.”

These were not fine-dining establishments frequented by wealthy city-dwellers, but they offered a rustic experience for open-minded working people who did not mind sometimes eating in a basement. Haley writes about a New York Times journalist who found that in the 1870s, a hearty five-course meal cost just 35 cents at a German restaurant (a little more than $8 today).

Like other cities in the latter half of the 19th century, Boston saw an increase in ethnic and immigrant-owned restaurants that catered to diners willing to expand their palates. A database developed through the Boston College history department shows 13 German-run restaurants in Boston by 1895. “The city [was] becoming more cosmopolitan, not some Yankee port town,” O’Connell says.

But trouble lay ahead for German restaurants in the later half of the 19th century and beyond, as large waves of immigrants from around the world settled in the United States with their culinary traditions in tow, providing American diners with more options for a night out. Between 1870 and 1900, according to the Library of Congress, the United States welcomed almost 12 million newcomers—primarily from Germany, England, and Ireland, but also a sizable population from China. “German food [was] not so much in decline but losing its distinctive spot almost from the moment it became popular,” says Haley, noting that the increasing ubiquity of other cultural foods diminished its popularity.

In the first half of the 20th century, the national ban on alcohol and two world wars dealt three successive blows to German dining. During and immediately following World War I, anti-German sentiment in the United States led German immigrants—at that time the largest non-English-speaking minority group in the nation—to hide their heritage for fear of retribution. American propaganda targeted Germany (“Beat back the Hun with Liberty Bonds”) through posters and flyers; the names of German foods were changed. This virulent strain of nativism included at least one public execution when, in 1918, Robert Prager, a German immigrant and bakery worker who was falsely accused of being a German spy, was hanged on a hackberry tree by a large crowd in southwestern Illinois.

Just two years later, the start of Prohibition dealt a financial blow to German restaurants by depriving them of beer imports. And by the early 1940s, anti-German attitudes were reignited by American involvement in World War II, which led many German Americans to assimilate rather than publicly embrace their heritage.

Here in Boston, though, Jacob Wirth survived, even as it suffered during the 1970s and 1980s due to skyrocketing crime and flourishing adult entertainment in the nearby Combat Zone. As Boston’s de facto red-light district, the heavily patrolled enclave offered prostitution, illegal drugs, and porn theaters while scaring away tourists and families. Sex and stabbings were the currency down Washington Street, and sordid tales of unchecked corruption in what resembled a police state did little to attract diners hungry for Old World cuisine. And yet Jacob Wirth found ways to keep the lights on.

By 1989, city leaders had approved plans to revitalize the Combat Zone, but it didn’t save Jacob Wirth in the long run. Shortly after the Washington Post published a death knell for German cuisine in 2018, detailing a litany of historic German restaurants that had closed their doors in recent years, former Jacob Wirth owner Kevin Fitzgerald announced he, too, was throwing in the towel, placing Jacob Wirth on the market for just north of a million dollars. While Fitzgerald initially cited his divorce as the reason for the sale, it seems as though a perfect storm of personal and financial troubles—including $1.43 million owed to more than 40 creditors—ultimately pushed Jacob Wirth onto the market. Bankruptcy court records show that, by late 2017, Fitzgerald’s Jacob Wirth Restaurant Company owed more than $68,000 in back pay to 25 employees (excluding the more than $10,000 owed to Fizgerald himself). One former restaurant worker filed an affidavit claiming he resigned in 2017 “because Jacob Wirth refused to pay me my wages.” Additionally, court filings reveal that the company owed $412,000 to the IRS, $175,130 to the Massachusetts Department of Revenue, and more than $50,000 in back rent.

Coupled with the June 2018 fire while the property was still on the market, it seemed like the end of Jacob Wirth. Then, last year, a group of six business partners and real estate investors came to the rescue, purchasing the beleaguered restaurant. City Realty, a Boston real estate firm, was charged with construction and development, while Royale Entertainment was set to run operations. The team was in the middle of renovations when the second fire tore through the property, giving it the distinction of being perhaps the unluckiest restaurant in Boston.

Jacob Wirth was a bastion of German cuisine in the 1950s. / Photo by Bill O’Connor/the Boston Globe

Even if the new ownership team does manage to rebuild, another question looms large: Could Jacob Wirth ever shake off the dust—both literally and metaphorically—to reclaim its spot as a cultural force in the city? Some food historians aren’t so sure. Haley believes that while there is some taste for more-modern German food among the public, Jacob Wirth would likely struggle trying to re-create what it once was. After all, says former Boston restaurant critic Corby Kummer, now a senior editor at the Atlantic and executive director of food and society at the Aspen Institute, “What Jacob Wirth had that made it so valuable was atmosphere. This old-time urban bar setting: rough and ready, hearty and fun.”

If, and when, it ever reopens, Jacob Wirth would not be the only game in town for German fare, though quality options remain few and far between. Bronwyn, a German and Central European–inspired eatery in Somerville’s Union Square, was opened in May 2013 by award-winning chef Tim Wiechmann and his wife, the restaurant’s namesake. Meanwhile, Karl’s Sausage Kitchen, a European grocer and Peabody institution since 1958, has weathered a national downturn in public demand for German cuisine by offering high-quality products and emphasizing authenticity, says co-owner Anita Gokey. “We have really stayed true to the German sausage-making traditions,” she explains.

Gokey, who co-owns Karl’s with her husband, welcomes regular customers from all over New England: German immigrants who still cook traditional fare, the descendants of German immigrants who remember bratwursts and frankfurters from their childhoods. But the art and labor of sausage-making is hard to pass on, she says, and a controversial Massachusetts law banning the sale of pork from pigs kept in tightly confined spaces has negatively affected food costs. “It’s like death by a thousand cuts between all of the expenses, the regulations, and the labor costs,” she says.

Despite the financial and cultural challenges, the owners of Jacob Wirth are resolute about reopening someday, believing there is still public demand for the restaurant. “People have reached out over the past year and a half to say how important [Jacob Wirth] was to them, that their grandfather was an original waiter, or that their parents had their first date there,” LaGuardia says. “People have so many memories, and it’s such a staple in the Boston scene that it’s made it more personal for us.”

The aftermath of this summer’s devastating fire. / John Tlumacki/the Boston Globe via Getty Images

Indeed, Reddit threads attest to the nostalgia many Bostonians feel for the dining institution. “NO!!! NOT JACOB WIRTH!!!” one person posted shortly after the fire. “This one hits hard.” Replied another: “I bike down Stuart Street on my way to work and was devastated to see all the windows blown out this morning. It’s such a beautiful building and an important piece of history, but I’m afraid this might be the last nail in the coffin. Feels like a stretch, but I hope it still comes back someday.”

A spokesperson from the city’s Office of Historic Preservation issued a statement that Boston is committed to rebuilding Jacob Wirth and working alongside architects, historians, and the current owners. The office described the “cherished Boston landmark” as an essential part of city history, an institution that “represents the legacy of generations who have contributed to the cultural and architectural tapestry of our city.”

Still, make no mistake: Reviving the restaurant demands deep pockets and a monumental effort—a daunting task that leaves many Bostonians hoping the elusive dream of Jacob Wirth hasn’t gone up in smoke forever.

First published in the print edition of Boston magazine’s November 2024 with the headline, “The Bierhaus That Burned Down. Twice.”

Boston, MA

Celtics midseason report card: Boston checked all boxes in impressive first half

Before the NBA season tipped off, we outlined a seven-step roadmap for the new-look, Jaylen Brown-led Celtics to exceed expectations in 2025-26.

Exactly halfway through, they’ve successfully checked six of those boxes, with the seventh still pending.

The result: Boston entered the week with the second-best record in the Eastern Conference, the fifth-best in the league, and top-three rankings in point differential (third), offensive rating (first) and net rating (second). Joe Mazzulla’s club has been, by almost any all-encompassing metric, one of the best in the NBA through 41 games.

Ahead of Monday night’s marquee matchup against the Detroit Pistons — No. 1 vs. No. 2 in the East — here’s a closer look at how Boston stacks up against those seven preseason benchmarks:

1. “Jaylen Brown looks like a legit No. 1”

“Boston’s clearest path to competitiveness involves Brown playing at an All-NBA level.”

Brown, who’d said for years that he could thrive as a No. 1 option if given the chance, has aced this test thus far, playing his way into the NBA MVP conversation while Jayson Tatum recovers from Achilles surgery. Owning the NBA’s second-highest usage rate behind Luka Doncic, he’s the league’s fourth-leading scorer (29.7 points per game) and is on pace for a career high in assists (4.8).

Though the 3-pointer has been the centerpiece of Boston’s offense under Mazzulla, Brown has found success by becoming one of the premier 2-point maestros, taking more shots per game from inside the arc than any other NBA player. He’s also averaging a career-best 7.3 free throws per game — despite frequent gripes about what he considers unfair officiating.

Simply put, he’s been exactly what this Celtics team needs.

2. “The most important players stay healthy”

“This current Celtics roster does not have (the) luxury (of proven depth). Losing a key player like Brown or White for any significant length of time could tank their season.”

Brown, who failed to reach the 65-game threshold for postseason awards last year, has appeared in all but three of Boston’s 41 games, sitting out two due to illness and one with back spasms. Starters Derrick White, Payton Pritchard and Sam Hauser have missed one game apiece. Top center Neemias Queta has missed two. That’s a total of eight DNPs for Boston’s current, Tatum-less starting five.

The Celtics’ key reserves have been regularly available, too. Sixth man Anfernee Simons has appeared in every game, and Jordan Walsh, Hugo Gonzalez, Luka Garza and Baylor Scheierman have been sidelined for a total of two (not including their occasional DNP-CDs).

Outside of Tatum, the only player on the roster who’s missed extended time is wing Josh Minott, who sat out the last six games with an ankle sprain. But Minott fell out of Mazzulla’s rotation in late December and wasn’t seeing meaningful minutes when he suffered his injury.

For context, at this point last season, Brown had missed seven games, Tatum three, Hauser seven, Jrue Holiday six, Luke Kornet six, Al Horford eight and Kristaps Porzingis 23.

3. “Anfernee Simons becomes a playable defender”

“Simons can score. Everyone knows that. … But can he be at least respectable on the defensive end? That’s the big question facing the 26-year-old guard.”

It was telling that, after Simons scored 39 points off the bench last Thursday in a come-from-behind win over the Miami Heat, Mazzulla spent much of his postgame news conference praising the guard’s improved defense.

Simons has gone from liability to legitimately impactful at that end since joining the Celtics over the summer, and those improvements have helped turn him into one of Boston’s most valuable contributors. After an uneven start to the season as he adjusted to his new bench role, the former Portland Trail Blazers starter owns the NBA’s fourth-best plus/minus since the beginning of December.

The big question surrounding Simons now is whether Boston’s front office views him (and his $27.7 million expiring contract) as a trade chip or an asset worth retaining. We’ll find out by the Feb. 5 trade deadline.

4. “The frontcourt exceeds its low expectations”

“The move from Kristaps Porzingis, Al Horford and Luke Kornet to Neemias Queta, Luka Garza, Chris Boucher and Xavier Tillman is an enormous downgrade on paper. The Celtics will need career years from at least one of these big men to field even a league-average frontcourt.”

The Celtics essentially took a “we’ll see how it goes and hope for the best” approach at the center position this past offseason — and so far, it’s worked.

Queta has been more than solid as a first-year starter (10.2 points, 8.2 rebounds, 1.2 blocks per game), and Garza, after being exiled to the end of the bench for much of December, has been a consistent difference-maker off the bench, excelling as a screener and on the offensive glass while shooting a team-best 48.9% from three. It hasn’t mattered that Boucher and Tillman — the Celtics’ two most experienced bigs — have hardly played.

Even Boston’s rebounding — an unsurprising early-season issue for a team that lost its top three big men and its leading rebounder (Tatum) from last year’s squad — has become a strength of late. With help from their crashing wings, the Celtics rank sixth in defensive rebounding rate and fourth in offensive rebounding rate since the start of December, and seventh in overall rebounding rate this season.

Still, trade rumors have linked the Celtics to several established big men, so they could make a move to bolster this group in the coming weeks.

5. “Multiple depth wings become reliable rotation players”

“Jordan Walsh? Baylor Scheierman? Josh Minott? Hugo Gonzalez? With no proven depth on the wing behind Brown and Hauser, the Celtics will need at least half of those inexperienced backups to play real roles this season.”

How about all four?

Gonzalez, an instant contributor as a 19-year-old rookie, boasts the NBA’s second-best individual net rating. The Celtics went 15-5 with Walsh — who’s having by far the best season of his three-year career — in their starting lineup. Scheierman has become an everyday rotation player, earning his playing time through deflections, drawn charges and the occasional timely 3-pointer. Even Minott has been a net positive, starting 10 games and playing big minutes as a small-ball center before falling down the pecking order. All four have swung games with their chaotic energy and hustle plays.

6. “The East is as wide-open as expected”

“Any argument for the Celtics remaining competitive this season should start with the quality of their conference.”

Seven Eastern Conference teams — from the second-ranked Celtics to the No. 8 Heat — entered the week with between 22 and 26 wins. The New York Knicks, Cleveland Cavaliers and Orlando Magic have underachieved relative to preseason hype, and the defending conference champion Indiana Pacers have cratered amid a tidal wave of injuries.

The Pistons sit comfortably atop the East standings, carrying a 4 1/2-game cushion into Monday night’s matchup. But is a franchise that’s won just two postseason games since 2008 an NBA Finals shoo-in? Hardly. The Celtics should be viewed as real conference contenders, especially if…

7. “Jayson Tatum returns for the stretch run (and looks like himself)”

“If Brown and Co. can scrap their way into the thick of the Eastern Conference playoff race, they couldn’t ask for a more helpful midseason addition than a healthy Tatum.”

By all accounts, Tatum is on or ahead of schedule in his Achilles rehab. The Celtics have insisted they will not rush him back, but a midseason comeback appears realistic. If he returns and looks like Tatum, even in a reduced role, watch out.

Boston, MA

Patriots defense makes statement after taking praise of Texans personally

FOXBORO — Mike Vrabel came straight off the practice field Friday to hold his final press conference of the week after four days of preparing for the Texans.

He’d been peppered with questions about the Texans’ vaunted defense all week, and for a moment, it looked like he was about to lose his cool when yet another reporter started with, “given the strength of the Texans’ defense…”

Vrabel closed his eyes, put his head down and rubbed his eyebrow with his thumb and pointer finger before keeping his calm and responding to the question about whether his team needed to be “perfect” this week.

Were they perfect in Sunday’s 28-16 win over the Texans? Absolutely not. But their own defense made a statement, forcing five turnovers and outshining the unit that some were comparing to the 1985 Bears and the “Legion of Boom” Seahawks.

So, was it fair to say that the Patriots’ defense took all that talk about the Texans’ defense personally this week?

“I’m sure they’re going to tell you in 30 seconds as soon as you guys go rushing out of here,” Vrabel said, smiling. “Again, they’re really good for a reason; they’ve shown it each and every week. But our guys are prideful men. And they want to compete and they want to win. And, again, they deserve the recognition that they’re going to get.

“They’re a top-five defense for a reason as well. Again, that’s how some of these things go. When it comes down to turnovers. And we’ve got to get back on track. We forced second-and-long, so we stopped the run. And I’m proud of each and every guy in there.”

For a team whose motto used to be “ignore the noise,” this new-age Patriots team heard everything, and they used it to deepen the chips on their collective shoulder.

And in the end, it didn’t matter that their own quarterback turned the ball over three times and fumbled twice more. It’s nearly impossible to lose when forcing five turnovers, and the Patriots defense — after having to hear all that talk, and seeing the graphic from ESPN’s “NFL LIVE” with all five pundits picking the Texans — was not going to accept defeat.

“It fueled the whole defense,” defensive tackle Milton Williams said after the game. “Ain’t nobody been talking about our defense all year. So, we’ll see what they gotta say today.”

Williams, who won Super Bowl LIX with the Eagles last season, was asked if he believes the Patriots have a championship-level defense. He answered immediately with, “Yes, definitely.”

The Patriots defense plays at a completely different level when they’re at full strength, like they were Sunday night with Williams, who had four pressures against the Texans, returning from injury in Week 18, linebackers Robert Spillane and Harold Landry coming back from their own ailments in the wild-card round of the playoffs, and defensive tackle Khyiris Tonga getting healthy for Sunday’s matchup.

Texans quarterback C.J. Stroud tossed four interceptions to three different players: cornerback Carlton Davis (twice), safety Craig Woodson and cornerback Marcus Jones, who returned his for a touchdown. Cornerback Christian Gonzalez forced a fumble, which Woodson recovered for his second turnover. The Patriots’ defense, which also caused havoc for Chargers quarterback Justin Herbert in the wild-card round of the playoffs, allowed just 241 net yards, sacked Stroud three times, hit him nine times, forced 27 incompletions, allowed 2.2 yards per carry and generated 27 pressures (per PFF) on 52 dropbacks.

“We got dogs on every level of our team,” Williams said. “Everybody’s doing their job at a high level. We all on the string and communication. Everything is just working together. Our coach is putting us in position to make plays, and we just execute at a high level. That’s all we need.”

While various defenders said all the praise the Texans defense received this week motivated the unit, both Williams and safety Jaylinn Hawkins said the players didn’t discuss it all week.

“We never talked about it,” Hawkins said. “We just seen it and kept it pushing.”

Outside linebacker K’Lavon Chaisson led the Patriots with seven pressures on Sunday and added a sack. He was in Stroud’s face on three of the QB’s four interceptions.

Vrabel credited the Patriots’ turnovers to complementary football, saying, “our turnovers are created by more than one guy.”

“Regardless of what the playcall was, see ball, get ball,” Chaisson said. “We had the opportunity to make those plays happen, and we did.”

It helped that the Patriots defense knew, coming into the game, that they couldn’t let Stroud operate out of clean pocket.

The Patriots praised Stroud all week, but he was coming off a wild-card round win over the Steelers when he was intercepted once and fumbled five times.

“If he’s kept clean, he can make any throw that any quarterback can make,” Williams said. “But under pressure, he puts the ball in harms away, and we tried to take advantage of it.”

The Patriots are going against another top defense next week when they face off against the Broncos. They will have more potential opportunities to generate turnovers, however, with Broncos backup Jarrett Stidham, a former Patriots draft pick, playing at quarterback in place of injured starter Bo Nix.

Boston, MA

FIRST ALERT: Storm to dump up to 9 inches of snow on southern New England today

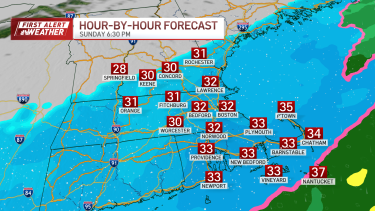

Another storm comes in today bringing the snow, especially from late morning through this evening.

A coastal storm passing just offshore will bring a widespread, wet snowfall to much of southern New England.

Here’s what’s in the forecast:

How much snow will we get in Massachusetts today? Other parts of New England?

Most of Southern New England is looking at 2–5 inch accumulations, with localized spots near 6 inches possible in southeastern Massachusetts and Rhode Island where the snow falls the steadiest and will have the most intensity.

Snow timing

Snow begins moving into Connecticut late morning, then spreads northeast into eastern Mass. after lunchtime.

It starts light, but the heaviest snow arrives late afternoon into the evening, when rates could reach ½ to 1 inch per hour, and even higher near the South Coast if temperatures cool just enough. Temperatures will be close to freezing, so this will be a heavy, wet snow, which can still accumulate even with readings hovering near or just above freezing.

Snow tapers off from west to east late tonight, generally between 10 p.m. and 2 a.m..

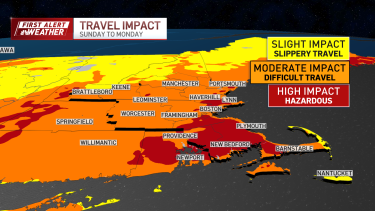

Travel impacts

Expect slippery roads, reduced visibility during heavier bursts, and slushy travel near the coast. Travel could be hazardous.

Winter weather advisory

A winter weather advisory is in effect from 7 a.m. today through 7 a.m. Monday for much of southern New England, plus parts of Vermont, New Hampshire and Maine.

Click here for active weather alerts

Live radar

This week’s forecast

Looking ahead, colder air rushes in behind this system Monday night as an arctic front sweeps through. Tuesday into early Wednesday will be the coldest stretch, with well-below-normal temperatures and wind chills near or below zero at times. The cold eases a bit by Wednesday afternoon into Thursday, with quieter weather overall, but passing front could bring a brief chance for light snow or rain showers, mainly near the coast. Below normal temperatures may return later in the week.

-

Montana1 week ago

Montana1 week agoService door of Crans-Montana bar where 40 died in fire was locked from inside, owner says

-

Virginia1 week ago

Virginia1 week agoVirginia Tech gains commitment from ACC transfer QB

-

Montana1 week ago

Montana1 week ago‘It was apocalyptic’, woman tells Crans-Montana memorial service, as bar owner detained

-

Minnesota1 week ago

Minnesota1 week agoICE arrests in Minnesota surge include numerous convicted child rapists, killers

-

Lifestyle4 days ago

Lifestyle4 days agoJulio Iglesias accused of sexual assault as Spanish prosecutors study the allegations

-

Oklahoma1 week ago

Oklahoma1 week agoMissing 12-year-old Oklahoma boy found safe

-

Education1 week ago

Education1 week agoVideo: A Viral Beauty Test Doesn’t Hold Water

-

Oregon1 week ago

Oregon1 week agoDan Lanning Gives Oregon Ducks Fans Reason to Believe