Health

AI identified these 5 types of heart failure in new study: ‘Interesting to differentiate’

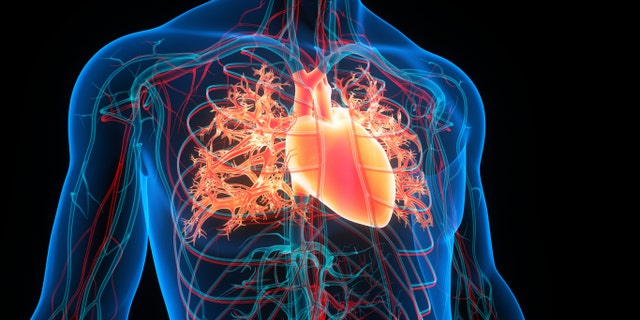

“Heart failure” is a catch-all term used to describe any condition in which the organ doesn’t work as it’s supposed to — but one person’s experience with the disease can be very different from someone else’s.

Researchers from the University College London (UCL) recently used machine learning — a type of artificial intelligence — to pinpoint five distinct types of heart failure, with the goal of predicting the prognosis for the different kinds.

“We sought to improve how we classify heart failure, with the aim of better understanding the likely course of disease and communicating this to patients,” said lead author Professor Amitava Banerjee from UCL in a press release announcing the study.

HEART DISEASE, THE SILENT KILLER: STUDY SHOWS IT CAN STRIKE WITHOUT SYMPTOMS

“Currently, how the disease progresses is hard to predict for individual patients,” he also said. “Some people will be stable for many years, while others get worse quickly.”

The five types of heart failure identified were early onset, late onset, atrial fibrillation (which causes an irregular heart rhythm), metabolic (linked to obesity but with a low rate of cardiovascular disease) and cardiometabolic (linked to obesity and cardiovascular disease), according to a press release on UCL’s website.

For each type of heart failure, the researchers determined the likelihood of the person dying within a year of diagnosis. The prognosis varied widely for the five subtypes, they found. (iStock)

“The five types of heart failure were on the basis of common risk factors, such as age at onset of heart failure, history of cardiac disease, history of cardiac risk factors such as diabetes and obesity, or atrial fibrillation (the commonest heart rhythm problem),” explained Banerjee in a statement to Fox News Digital.

For the study, published in the journal Lancet Digital Health, the researchers analyzed data from more than 300,000 U.K. adults aged 30 and older who had experienced heart failure over a 20-year period.

HEART DISEASE RISK COULD BE AFFECTED BY ONE SURPRISING FACTOR, NEW STUDY FINDS

“Four methods of machine learning were used to cluster individuals with heart failure in electronic health data by their baseline characteristics,” said Banerjee. “The method and the number of clusters that ‘fit’ best to the data were selected.”

For each type of heart failure, the researchers determined the likelihood of the person dying within a year of diagnosis. The prognosis varied widely for the five subtypes, they found.

The five-year mortality risk was 20% for early onset, 46% for late onset, 61% for atrial fibrillation-related, 11% for metabolic and 37% for cardiometabolic, according to the press release.

The main limitation of the new study from UCL was that the researchers didn’t have access to any imaging data, which is most commonly used to diagnose and predict risk in heart failure. (iStock)

For health professionals, Banerjee recommends that they ask their heart failure patients about common risk factors to help them understand the subtype they have.

“Researchers also need to test how usable, generalizable and acceptable these subtypes defined in our study are in clinical practice,” he added.

“They should also consider whether studies such as ours, which use AI, can help inform a better understanding of disease processes and drug discovery.”

The research team also developed an app for physicians that would enable them to determine which subtype of heart failure a patient has — with the goal of better predicting risk and keeping patients informed.

AI AND HEART HEALTH: MACHINES DO A BETTER JOB OF READING ULTRASOUNDS THAN SONOGRAPHERS DO, SAYS STUDY

Dr. Ernst von Schwarz, a triple board-certified clinical and academic cardiologist at UCLA in California, reviewed the results of UCL’s study.

“For clinicians, it is interesting to differentiate heart failure according to prognosis, which usually is not done in the clinical setting,” he told Fox News Digital. “Heart failure is generally seen as an incurable, chronic, progressive disease with poor long-term outcomes.”

“Heart failure is generally seen as an incurable, chronic, progressive disease with poor long-term outcomes.”

“Studies like this might help clinicians make a more appropriate risk assessment according to the etiology of heart failure,” von Schwarz added.

In particular, the very high mortality rate for atrial fibrillation-induced heart failure highlights the importance of aggressively managing this common arrhythmia, he said.

Researchers used machine learning — a type of artificial intelligence — to pinpoint five distinct types of heart failure. (iStock)

The mortality predictions for the five subtypes are “by far the most interesting part of this data,” according to Dr. Matthew Goldstein, a physician at Cardiology Consultants of Philadelphia, who also reviewed the study findings.

“This may help us guide who is at risk for dying suddenly, and thus, who needs protection with a defibrillator and who does not,” he added.

AI shows promise, but limitations remain

While Goldstein recognizes that AI is becoming more common in general, he believes its application is medicine has shown “somewhat less success.”

He told Fox News Digital, “It is, however, good at looking for patterns that are too complicated for the human mind to see.”

AI TECHNOLOGY CATCHES CANCER BEFORE SYMPTOMS WITH EZRA, A FULL-BODY MRI SCANNER

“Some of the more common utilizations are automatic readings of radiology studies to make sure that nothing is missed and emerging use in EKG interpretation to suggest underlying pathology,” he added.

In terms of using AI to classify heart failure, Goldstein noted that this is only a retrospective study and will need to be proven for future cases in order to be truly useful.

Looking ahead

The main limitation of the new study was that the researchers didn’t have access to any imaging data, which is most commonly used to diagnose and predict risk in heart failure.

“However, imaging markers alone do not predict mortality and other outcomes,” Banerjee said.

“The fact that we were able to use routinely collected data without this imaging data to predict subtypes and outcomes relatively well suggests that the imaging biomarkers alone may not be the best way to characterize and study heart failure at population scale.”

Using these findings as a foundation, Professor Banerjee of UCL said the next step is to determine whether these heart failure classifications can make a practical difference to patients. (iStock)

The next step, Banerjee said, is to determine whether classifying various heart failures can make a practical difference to patients — “whether it improves predictions of risk and the quality of information clinicians provide, and whether it changes patients’ treatment.”

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR OUR HEALTH NEWSLETTER

Cost-effectiveness is another consideration, he added.

The UCL research team previously used similar methods to identify subtypes in chronic kidney disease.

Looking ahead, Banerjee expects that machine learning will be used to analyze many types of routinely collected medical data and to identify subtypes of different diseases.

Health

Video: Why So Many Women Feel Pain During Their C-Sections

new video loaded: Why So Many Women Feel Pain During Their C-Sections

Recent episodes in Latest Video

Whether it’s reporting on conflicts abroad and political divisions at home, or covering the latest style trends and scientific developments, Times Video journalists provide a revealing and unforgettable view of the world.

Whether it’s reporting on conflicts abroad and political divisions at home, or covering the latest style trends and scientific developments, Times Video journalists provide a revealing and unforgettable view of the world.

Health

Why sitting around a campfire might be the health boost you didn't know you needed

NEWYou can now listen to Fox News articles!

Lighting a campfire and watching as the flames grow and flicker can feel therapeutic — for good reason.

Between the light, heat and crackling sound, sitting around a campfire can be a relaxing experience — and experts agree that it can even benefit your mental health.

Research published in the journal Evolutionary Psychology has noted “significant reductions” in blood pressure associated with exposure to a crackling fire.

BEACH DAYS BENEFIT MENTAL HEALTH AND WELL-BEING AS VISITS PROVIDE ‘SEA THERAPY’

Campfires or firepits can also improve social interactions, researchers noted.

M. David Rudd, Ph.D., professor of psychology and director of the Rudd Institute for Veteran and Military Suicide Prevention at the University of Memphis, agreed that the natural setting of campfires is “likely effective” for soothing the mind and engaging with others.

Sitting by a fire can improve social connections, according to research. (iStock)

People sitting around a fire are “digitally disconnected” and isolated from technology distractions and the demands of daily life, the expert noted.

“The context is disarming and socially engaged by its very nature, generating implicit expectations of engagement and interaction,” Rudd told Fox News Digital in an interview.

EXTREME HEAT AFFECTS THE BRAIN — HERE’S HOW TO PROTECT YOUR COGNITIVE HEALTH

“We all have memories of being around a campfire and hearing stories — or at least we’ve heard stories about what it means to be around a campfire.”

These expectations foster a “supportive, non-threatening environment where people don’t feel judged or pressured to engage,” Rudd said.

A psychologist described campfires as a “supportive, non-threatening environment where people don’t feel judged or pressured to engage.” (iStock)

Campfires may encourage those who are “hesitant, anxious or unwilling to engage elsewhere” to connect with others and share personal experiences, he added.

Jessica Cail, Ph.D., assistant professor of psychology at Pepperdine University in California, pointed out the association of fire with relaxation, comparing fires to a “social hub where people come together for warmth, light, food and protection.”

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR OUR HEALTH NEWSLETTER

Many holiday celebrations tend to involve fire, and some homes have fireplaces geared toward gathering and connecting, Cail noted in a separate interview with Fox News Digital.

“Being in nature involves more of a soft focus … giving our brains a chance to rest and restore.”

“Given these positive associations, it should not be a surprise that these feelings of relaxation and safety can help facilitate social communication and counteract negative feelings, whether they’re explicitly shared or not,” she added.

Fire is also associated with ritual and transition, such as the use of advent candles or the therapeutic practice of writing regretful or traumatic thoughts down on paper, throwing them into a fire and watching them burn, Cail noted.

Fires are “evolutionarily associated” as a social hub, and can reduce stress, anxiety and blood pressure, research has shown. (iStock)

Nature is restorative, helping to counteract modern life’s numerous demands and the need to stay hyper-focused on specific tasks, the expert added.

“This is fatiguing for our brains,” Cail said.

For more Health articles, visit www.foxnews.com/health

“Being in nature involves more of a soft focus (the sight of trees, the smell of grass, the sound of birds), giving our brains a chance to rest and restore.”

“This break from ruminating on stress may be why so many researchers have found ‘doses of nature’ to be effective in reducing both depression and anxiety.”

Detaching from daily demands and technology, and immersing yourself in nature, can help support mental health, experts say. (iStock)

Campfires are often associated with leisure in nature, which is an important component of mental health, especially for those with mental illnesses, according to Cail.

The expert emphasized that changing your environment can also “change your mind.”

“Unless your trauma took place in nature or around a fire, a change in environment like camping can break you out of that associative headspace, giving you a fresh outlook,” she added.

Health

New GLP-1 Called MariTide Shows 20% Weight Loss—Without a Plateau

Use left and right arrow keys to navigate between menu items.

Use escape to exit the menu.

Sign Up

Create a free account to access exclusive content, play games, solve puzzles, test your pop-culture knowledge and receive special offers.

Already have an account? Login

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoSee How Trump’s Big Bill Could Affect Your Taxes, Health Care and Other Finances

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week ago16 Mayors on What It’s Like to Run a U.S. City Now Under Trump

-

Politics6 days ago

Politics6 days agoVideo: Trump Signs the ‘One Big Beautiful Bill’ Into Law

-

Science1 week ago

Science1 week agoFederal contractors improperly dumped wildfire-related asbestos waste at L.A. area landfills

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: Who Loses in the Republican Policy Bill?

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoCongressman's last day in office revealed after vote on Trump's 'Big, Beautiful Bill'

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoMeet Soham Parekh, the engineer burning through tech by working at three to four startups simultaneously

-

World6 days ago

World6 days agoRussia-Ukraine war: List of key events, day 1,227