Entertainment

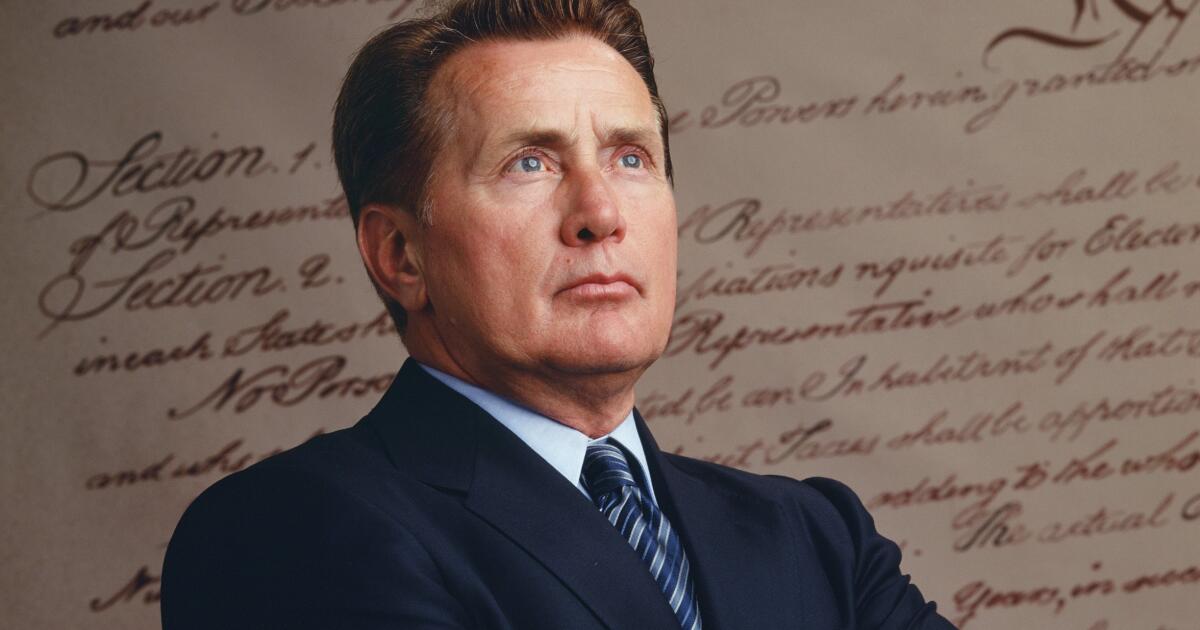

Opinion: Tempted to vote for Jed Bartlet in 2024? 'The West Wing' was always a fantasy

As another terrifyingly significant presidential election nears, it’s hard not to fantasize about how different things could be. Imagine, for instance, having a president who put deeply held values above the pressures of their biggest donors. Imagine one who was able to truly listen and learn when faced with issues they didn’t understand rather than adhere to whatever stance happened to be the most politically convenient at the time. Imagine, even, a president who inspired you, who made you feel a glow of patriotism, skeptical as you might be of the concept. In short, imagine Josiah Edward “Jed” Bartlet, president of the United States as envisioned by Aaron Sorkin and brought to life by Martin Sheen across seven seasons of the award-winning and critically acclaimed NBC series “The West Wing.”

Two of the show’s cast members, Melissa Fitzgerald (who played Carol Fitzpatrick, assistant to the White House press secretary) and Mary McCormack (who played deputy national security advisor Kate Harper), certainly still believe in the show’s sticking power as well as its overall positive framing of politics. They have written a book about it that is plainly geared toward existing fans of the show: “What’s Next: A Backstage Pass to the West Wing, Its Cast and Crew, and Its Enduring Legacy of Service.”

Look, it’s true: Every so often, I make hot chocolate in my “Bartlet for America” mug and sip it wistfully, imagining a world in which we’d had a President Bartlet instead of a second President Bush, perhaps followed by a President Santos — the character played by Jimmy Smits who had sweeping, truly inspired education reform plans. It’s a lovely dream, a White House that’s more “West Wing” and less “Veep,” functional and nearly scandal-free, earnestly dedicated to bettering the lives of everyday Americans by doing the slow yet essential work of policy change.

Yes, I know this is extremely naive; yes, I’m aware that Bartlet was problematic in plenty of ways, as were his staffers; and yes, I know that “The West Wing” was, in many ways, a liberal fever dream that bought into American exceptionalism and the ideals of patriotism. But that’s just it: The show was a fantasy, one that gestured at an idea of how things could be, but that wasn’t trying to claim that this was how things really were. Sorkin himself insisted that “first and foremost, if not only, this is entertainment. ‘The West Wing’ isn’t meant to be good for you. … Our responsibility is to captivate you for however long we’ve asked for your attention.”

And entertain us it did, across more than 150 episodes, some more memorable than others, but all including at least one rousing monologue that made this viewer, at least, believe in the possibility of a government that really works, or that really tries to work, or that really wants to work. It helps that I first watched bits of it as a tween, long before I’d moved to the States, when my trips to California were strictly family visits during which I was loved and spoiled by my grandparents and aunts with as much frozen yogurt as I wanted, unrestricted TV time during which I enjoyed more channels than I knew what to do with and endlessly fascinating commercials for toys I would never get, and best of all, bookstores so large I could get lost in them. It felt like a more innocent time.

But, of course, it wasn’t. “The West Wing” was airing as George W. Bush took office following a close and contested election. It was on TV when 9/11 happened, as the Patriot Act was signed, and as the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq were launched. The show offered a rosy alternative, which appealed especially to a certain income bracket; its biggest chunk of viewers, according to a 2001 study, were earning more than $70,000 a year — or, in today’s money, more than $120,000. Largely sheltered from systemic injustices contributing to and caused by poverty, affluent people experienced fewer of our government’s shortcomings and probably found the show’s vision more plausible than it was.

As a (rather sheepish) devotee of the show, I bought into it too, especially the first couple of times I watched it front to back, in my late teens and early 20s. It managed to make the American political process — which I found deeply baffling, having never learned how it worked in school — exciting. Partially, I’m sure, it was the speed of the quippy dialogue, which Sorkin is famous for, as well as the way the show was shot, its long walk-and-talk scenes lending a sense of urgency to matters of dry policy. The humor was helpful too, and sometimes educational. I’ll never forget the Big Block of Cheese Day episode during which deputy communications director Sam Seaborn is required to meet with a ufologist — and Press Secretary C.J. Cregg and Deputy Chief of Staff Josh Lyman learn (along with the rest of us) that the maps we’ve all grown up with are both imperialistic and frankly just wrong.

But as funny and inspiring (often at the same time, as in the brilliant two-parter “20 Hours in America”) as the show can be, there are glaring issues in it. When I rewatched it more recently, I was incredibly disturbed, for instance, by the dynamic between Lyman and his assistant, Donna Moss. What was framed as a cute “will they/won’t they” relationship between boss and devoted employee now read to me as not only extremely unprofessional but even downright abusive, with Donna bearing the brunt of Josh’s temper tantrums and putting up with being constantly belittled by him. But it’s more than the interpersonal dynamics; the show’s occasionally over-the-top optimism and sincere belief in the United States as the greatest nation on Earth — not to mention its very white casting and casual yet consistent sexism — has, speaking anecdotally, made it feel cringey to many leftists of my generation.

The old critiques about the show’s idealism still ring true. Cynicism about and frustration with the slow gears of government have likely always existed throughout the left-right spectrum. Now, with social media adding a second-by-second commentary on an already speedy 24-hour news cycle, these sentiments feel much louder and more visible.

The authors of “What’s Next” don’t address the ways the show has aged poorly. They’re instead relentless in pointing to its positives, and to be fair, when it was originally airing there was no other TV show depicting government functions, and so the policies that “The West Wing” explored were likely eye-opening to many of its viewers. An episode in the first season, for instance, includes a compelling argument for financial reparations for the descendants of enslaved Black people, a concept as old as abolition but which plenty of the show’s viewers might have never encountered before.

This particular example isn’t mentioned in the book, though, which focuses instead on the broad idea of service and lionizes the show’s cast members for their various social and political activism. Many have worked to support veterans and treatment courts, which emphasize rehabilitation for individuals with substance use disorders. “What’s Next” is a cheerleading text, a fun and breezy read that doesn’t delve into any cringe aspects or difficulties on set.

But “The West Wing” would, like almost any piece of enduring media, only suffer from an insistence that it’s perfect. The show is a messy piece of very entertaining — and occasionally educational — television, full of extremely talented actors giving incredible performances, but it’s not a road map for reality, nor should it be.

After President Biden’s debate debacle this summer, the show’s creator, Sorkin, penned a bizarre op-ed suggesting that the Democrats nominate Mitt Romney, a moderate Republican, for president, a strategy to poach enough conservative voters to keep former President Trump from regaining power. But when Biden stepped out of the race, Sorkin quickly took back the suggestion. His op-ed was, depending on whom you asked, a frustrating or entertaining thought experiment, but it should never have been seen as real advice for the real world. Like “The West Wing,” it was a break from reality.

Ilana Masad is a books and culture critic and author of “All My Mother’s Lovers.”

Movie Reviews

Movie Review: Here comes “THE BRIDE!”, audacious and wild – Rue Morgue

That’s both a promise and a challenge she delivers, since what follows may rub some viewers the wrong way. Yet Gyllenhaal’s full-throttle commitment to her vision is compelling in and of itself, and she has marshalled an absolutely smashing-looking and -sounding production. The story proper begins in 1936 Chicago, which, like everything and everyplace else in the movie, has been luminously shot by cinematographer Lawrence Sher and sumptuously conjured by production designer Karen Murphy. Her involvement is appropriate given that her previous credits include Bradley Cooper’s A STAR IS BORN and Baz Luhrmann’s ELVIS, since among other things, THE BRIDE! is a nostalgic musical. Its Frankenstein (Christian Bale), who has taken the name of his maker, is obsessed with big-screen tuners, and imagines himself in elaborate song-and-dance numbers. (Considering the reception to JOKER: FOLIE À DEUX, one must applaud the daring of Warner Bros. for greenlighting another expensive film in which a tormented protagonist has that kind of fantasy life.)

THE BRIDE! may be revisionist on many levels, but its characterization of its “monster” holds true to past screen incarnations from Karloff’s to Elordi’s: His scarred appearance masks a lonely soul who desires companionship. Frankenstein has arrived in Chicago to seek out Dr. Cornelia Euphronious (Annette Bening), correctly believing she has the scientific know-how to create an appropriate mate for him. Rather than piece one together, Dr. Euphronious resurrects the corpse of Ida (Jessie Buckley), whose consorting with underworld types led to her brutal death. Previously chafing against the man’s world she inhabited in life, she becomes even more defiant and unruly as a revenant, apparently possessed by the spirit of Shelley herself, declaiming in free-associative sentences and quoting rebellious literature.

Buckley, currently an Oscar favorite for her very different literary-inspired role in HAMNET, tears into the role of the Bride (who now goes by the name Penny) with invigorating abandon that bursts off the screen. Unsure of her identity yet overflowing with self-confident bravado, she’s the opposite of the sensitive “Frank,” but they’re united by the world that stands against them. That becomes literal when a violent incident sends them on the lam, road-tripping to New York City and beyond, on a trail inspired by the films of Ronnie Reed (Jake Gyllenhaal), Frank’s favorite song-and-dance-man star.

With THE BRIDE!, Gyllenhaal has made a film that’s at once her very own and a feverish homage to all sorts of cinema past and present. It’s a horror story, a lovers-on-the-run movie, a crime thriller, a musical and more, and historical fealty be damned if it makes for a good scene (as when Penny and Frank sneak into a 3D movie over a decade before such features became popular). In-references are everywhere: It might just be a coincidence that the couple’s travels take them past Fredonia, NY (cf. “Freedonia” in the Marx Brothers’ DUCK SOUP), but it’s certainly no accident that the former Ida is targeted by a crime boss named Lupino, referencing the actress and pioneering filmmaker whose works included noirs and women’s-issues stories. Penny’s exploits lead legions of admiring women to adopt her look and anarchic attitude, echoing the first JOKER (while a headline calls them “Twisted Sisters”), and the use of one Irving Berlin song in a Frankensteinian context immediately recalls a classic comedic take on the property.

Whether the audience should be put in mind of a spoof at a key point in a film with different goals is another matter. At times like these, Gyllenhaal’s pastiche ambitions overtake emotional investment in the story. As strong as the two lead performances are (Bale is quite moving, conveying a great deal of soul from behind his extensive prosthetics), it’s easier to feel for them in individual scenes than during the entire course of the just-over-two-hour running time. The diversions can be entertaining, to be sure, but they also result in an uncertainty of tone. The dissonance continues straight through to the end, where the filmmaker’s choice of closing-credits song once again suggests we’re not supposed to take all this too seriously.

There’s nonetheless much to admire and enjoy about THE BRIDE!, and this kind of risk-taking by a major studio is always to be encouraged (especially considering that we’ll see how long that lasts at Warner Bros. once Paramount takes it over). Beyond the terrific work by the aforementioned actors, there’s fine support from Peter Sarsgaard and Penelope Cruz as detectives on Penny and Frank’s heels, with Sandy Powell’s lavish costumes and Hildur Guðnadóttir’s rich, varied score vital to fashioning this fully imagined world. Kudos also to makeup and prosthetics designer Nadia Stacey and to Chris Gallaher and Scott Stoddard, who did those honors on Frank, for their visceral, evocative work. Uneven as it may be, THE BRIDE! is also as alive! as any film you’ll likely see this year.

Entertainment

These 3 Disney movie songs, animated with sign language, are headed to Disney+

New animated sequences of songs from “Encanto,” “Frozen 2” and “Moana 2” are headed to Disney+.

Disney Animation announced Wednesday that “Songs in Sign Language,” comprised of three musical numbers from recent Disney movies newly reimagined in American Sign Language, will debut April 27 in honor of National Deaf History Month.

Directed by veteran Disney animator Hyrum Osmond, “Songs in Sign Language” will feature fresh animation for “Encanto’s” chart-topper “We Don’t Talk About Bruno,” “Frozen 2’s” poignant ballad “The Next Right Thing” and “Moana 2’s” anthem “Beyond.” Produced by Heather Blodget and Christina Chen, the new versions of these songs were created in collaboration with L.A.-based theater company Deaf West Theatre.

“In the majority of cases, we created entirely new animation,” Osmond said in a press statement. “There were a lot of adjustments that we had to do within the animation to be true to the original intention.”

Deaf West Theatre artistic director DJ Kurs, sign language reference choreographer Catalene Sacchetti and a group of eight performers from Deaf West worked together to craft and choreograph the ASL version of the musical numbers for “Songs in Sign Language.” The creatives focused on being true to the concepts and emotion of the songs rather than direct translations of the lyrics.

Kurs said his team jumped at the chance to collaborate and integrate ASL into “the fabric of Disney storytelling.”

“Disney stories are the universal language of childhood,” Kurs said in a statement. “The chance to bring our language into that world was a historic opportunity to reach a global audience. Working on this project was very emotional. For so long, we have known and loved the artistic medium of Disney Animation. Here, the art form was adapting to us. I hope this unlocks possibilities in the minds and hearts of Deaf children, and that this all leads to more down the road.”

Osmond, who led a team of more than 20 animators on this project, said animation was the perfect medium to showcase sign language, which he described as “one of the most beautiful ways of communication on Earth.” The director, whose father is deaf, also saw this project as an opportunity to connect with the Deaf community.

“Growing up, I never learned sign language, and that barrier prevented me from really connecting with my dad,” Osmond said. “This reimagining of Disney Animation musical numbers helps bring down barriers and allows us to connect in a special way with our audiences in the Deaf community. I’m grateful that the Studio got behind making something so impactful.”

Movie Reviews

Maxime Giroux – ‘In Cold Light’ movie review

(Credits: Far Out / Elevation Pictures)

Maxime Giroux – ‘In Cold Light’

The action is relentless in the complex thriller In Cold Light, a tense combination of crime and fugitive tale and family drama. It is the third feature and first English language film by Maxime Giroux, best known for a very different kind of film, the critically acclaimed 2014 drama Felix & Meira.

The tension and high energy of In Cold Light almost overwhelm the film, but are relieved, barely, by moments of character development and introspection that keep the audience pulling for the restrained and outwardly cold main character.

Speaking at the film’s Canadian premiere, director Giroux admitted he found creating an action film a challenge. Part of his approach was using very minimal dialogue, especially for the central character, letting the action speak for itself, and allowing silence to intensify suspense. Giroux has said he likes the lack of dialogue and speaks highly of the importance of silence in cinema; he prefers using “physical aspects of communication” in his films.

Young Ava Bly (Maika Monroe) is a competent and businesslike drug dealer, working in partnership with her brother Tom (Jesse Irving) and a small team. As the film begins, Ava has just been released from a brief prison sentence. She is hoping to return to her former position, but her brother’s associates consider her a risk due to her recent incarceration. While she works to re-establish herself, a shocking encounter with a corrupt police officer sends Ava’s life into chaos and forces her to go on the run.

Ava’s fugitive experience introduces a new character, to whom Ava turns for help: her father, Will Bly, played by Troy Kotsur, known for his excellent performance in CODA. Their first interaction is handled in a fascinating way, as Will is deaf and the two communicate through sign language. This, of course, provides another form of the silent interaction the director prefers; he explained that much of the father-daughter interaction was rewritten with the actor in mind. Their conflict is nicely expressed through a scene in which their initial conversation is intermittently cut off by a faulty light which goes out periodically, making communication through sign momentarily impossible, nicely expressing the rift between father and daughter.

As Ava continues to evade danger, her escape becomes complicated by new information, placing her in a painful dilemma. We gradually learn more about Ava, her background, and her character through occasional flashbacks and glimpses of her dreams. The plot becomes more complex and more poignant, and gains features of a mystery as well as an action tale, as she is pressed to choose from among equally unacceptable alternatives.

The climax of her efforts to protect both herself and those close to her comes to a head as she meets with the director of a rival drug gang. Veteran actress Helen Hunt is perfect in the minor but significant role of Claire, the rival drug lord, who plays odd mind games with Ava in an intriguing psychological fencing match. It’s an unusual scene, in which Ava’s personality is made clearer, and Claire’s understated dominance and casual speech do not quite conceal the threat she represents.

The frantic pace and emotional turmoil are enhanced by the camera work, which tends to focus tightly on Ava, and by a harsh, minimal musical score that sets the tone without distracting from the action. Giroux chose to shoot the film in Super 60; he describes digital as “too perfect” for the look he was going for, and since “Ava is rough,” the film portrays her better. The director describes the entire movie as “rough,” in fact, and deliberately chose a dark, washed-out look for much of the footage, occasionally using light and colour, in the form of fireworks, lightning, or a colourful carnival, to both relieve and emphasise the darkness.

The dynamic, intense story holds the attention in spite of the lengthy, sometimes repetitive chase scenes and subdued dialogue. Ava’s predicament, and the difficult decisions she is forced to make, are made surprisingly relatable, from the initial disaster that starts the action to the surprising flash-forward that concludes the film, on as high a note as the situation could allow. Fans of action movies will definitely enjoy this one.

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoExclusive: DeepSeek withholds latest AI model from US chipmakers including Nvidia, sources say

-

Massachusetts1 week ago

Massachusetts1 week agoMother and daughter injured in Taunton house explosion

-

Wisconsin3 days ago

Wisconsin3 days agoSetting sail on iceboats across a frozen lake in Wisconsin

-

Maryland4 days ago

Maryland4 days agoAM showers Sunday in Maryland

-

Denver, CO1 week ago

Denver, CO1 week ago10 acres charred, 5 injured in Thornton grass fire, evacuation orders lifted

-

Florida4 days ago

Florida4 days agoFlorida man rescued after being stuck in shoulder-deep mud for days

-

Oregon6 days ago

Oregon6 days ago2026 OSAA Oregon Wrestling State Championship Results And Brackets – FloWrestling

-

Massachusetts2 days ago

Massachusetts2 days agoMassachusetts man awaits word from family in Iran after attacks