Movie Reviews

Darren Aronofsky’s The Whale is hate disguised as tough love

Polygon has a group on the bottom on the 2022 Toronto Worldwide Movie Competition, reporting on the horror, comedy, drama, and motion motion pictures meant to dominate the cinematic dialog as we head into awards season. This evaluate was printed together with the movie’s TIFF premiere.

A24’s The Whale drops all of Darren Aronofsky’s worst tendencies right into a fats go well with. It’s an train in abjection within the mode of Aronofsky’s torturous Requiem for a Dream, nevertheless it’s targeted on an much more susceptible goal than Requiem’s addicts. It’s additionally stuffed with the pet biblical wankery of Mom!, Noah, and The Fountain, however centered on a Christ determine whose masochistic superpower is to soak up the cruelty of everybody round him and retailer it safely inside his large body.

To be honest, some folks get pleasure from this sort of miserabilism. However these viewers are additionally warned that not solely is that this movie troublesome to endure and more likely to be actively dangerous to some audiences, it’s additionally a self-serving reinforcement of the established order — which is among the most boring issues a film could be.

For a film that, in probably the most beneficiant studying doable, encourages viewers to contemplate that perhaps there’s a painful backstory behind our bodies they contemplate “disgusting” (the film’s phrase), The Whale appears to have little curiosity within the perspective of its protagonist, Charlie (Brendan Fraser). Charlie is a middle-aged divorcé dwelling in a small residence someplace in Idaho, the place he teaches English composition courses on-line. Charlie by no means turns his digicam on throughout lectures, as a result of he’s fats — very fats, round 600 kilos. Charlie has bother getting round with out a walker, and he has adaptive gadgets like grabber sticks stashed round his home.

If an alien landed on Earth and questioned whether or not the human species discovered its largest members engaging or repellent, The Whale would clearly talk the reply. Aronofsky turns up the foley audio each time Charlie is consuming, to emphasise the moist sound of lips smacking collectively. He performs ominous music below these sequences, so we all know Charlie’s doing one thing very dangerous certainly. Fraser’s neck and higher lip are perpetually beaded with sweat, and his T-shirt is soiled and coated in crumbs. At one level, he takes off his shirt and slowly makes his strategy to his mattress, sagging rolls of prosthetic fats dangling off his physique as he slouches towards the digicam just like the tough beast he’s. In case viewers nonetheless don’t get that they’re supposed to search out him disgusting, he recites an essay about Moby-Dick and the way a whale is “a poor huge animal” with no emotions.

And that’s simply what Aronofsky communicates about him by means of the movie’s directing. The story in The Whale’s first half is a gauntlet of humiliation, starting as an evangelical missionary named Thomas (Ty Simpkins) walks in on Charlie as he’s having a coronary heart assault, homosexual porn nonetheless taking part in on his laptop computer from a pathetic try at masturbation. Charlie’s nurse and solely good friend, Liz (Hong Chau), is usually variety to him, though she allows him with meatball subs and buckets of fried hen. So is Thomas, though he’s much less all in favour of Charlie as an individual than as a soul to save lots of. However Charlie’s 17-year-old daughter Ellie (Sadie Sink) brazenly despises him, and says probably the most vicious issues she will be able to consider to punish Charlie for leaving her and her mother, Mary (Samantha Morton), when Ellie was 8.

Aronofsky and author Samuel D. Hunter (adapting his personal stage play) don’t reveal the condescending level of all of this till the second half of the film: Charlie is a saint, a Christ determine, the fats man who so cherished the world that he let folks in his life deal with him like full dogshit with a purpose to absolve them of their hatred, and him of his sins. In the meantime, a subplot involving Thomas’ previous life in Iowa makes the weird assertion that persons are really attempting to assist once they deal with others unkindly, which may solely be true if the goal of that hostility doesn’t know what’s good for them. So which is it? Ought to an individual flip the opposite cheek, or be merciless to be variety? Relies on whether or not they’re fats, it appears. Charlie by no means feedback on different characters’ smoking and consuming, however they certain do touch upon his weight.

Maybe probably the most irritating factor about The Whale is how shut it involves some kind of perception. Aronofsky and Hunter simply wanted to indicate some empathy and curiosity about folks Charlie’s dimension, fairly than paternalistically guessing at their motivations. The principle perpetrator here’s a plot level the place Charlie refuses to go to the hospital, despite the fact that his blood stress is dangerously excessive and he’s displaying signs of congestive coronary heart failure. At first, he lies to Liz and says he doesn’t have the cash to pay the large medical payments he’d rack up as an uninsured affected person. Then it emerges that Charlie has greater than $100,000 tucked away in financial savings.

The Whale understands this as a mixture of selflessness — he’s hoping to offer that cash to Ellie after he dies — and suicidality. What offers away Aronofsky and Hunter’s projection about Charlie’s motivations is that intensive research have proven why overweight sufferers keep away from medical remedy, and it has nothing to do with self-sacrificing messiah-complex bullshit. Medical doctors are simply merciless to fats folks — and disproportionately more likely to dismiss, demean, and misdiagnose them.

The opposite irritating factor is that Brendan Fraser is definitely a major asset within the title function. He performs Charlie as a wise, humorous, considerate man who loves language and creativity, and refuses to let the tragic circumstances of his life flip him right into a cynic. He sees the most effective in everybody, even Ellie, whose insults he counters with affirmations and assist. (She’s hurting, you see.) Fraser’s eyes are variety, and his eyebrows are furrowed with disappointment and fear.

But when there’s any rage behind these eyes, we don’t see it. If Charlie is simply telling folks what they need to hear in hopes of minimizing their abuse, that doesn’t translate. The movie appears happy along with his surface-level protestations that he’s nice and joyful and only a naturally optimistic man, which once more betrays its lack of curiosity in Charlie’s interior emotional life — Fraser’s delicate try to discover a man contained in the image however.

Aronofsky and his group are extra all in favour of their very own cleverness. A few of the barbs thrown round in Charlie’s residence are literally fairly humorous. (The film brazenly reveals its theatrical roots: The complete story takes place throughout the confines of Charlie’s residence and entrance porch.) Chau particularly brings a prickly heat to her function as Liz, the kind of good friend whose love language is playful insults, and whose goal in life is as a fierce defender. Liz is hurting, too, after all; everyone seems to be right here. However whereas everyone seems to be hurting, Charlie has to endure probably the most for it.

In case you have a look at The Whale as a fable, its ethical is that it’s the duty of the abused to like and forgive their abusers. The film thinks it’s saying, “You don’t perceive; he’s fats as a result of he’s struggling.” But it surely finally ends up saying, “You don’t perceive; now we have to be merciless to fats folks, as a result of we are struggling.” Aronofsky and Hunter’s biblical metaphor apart, fats folks didn’t volunteer to function repositories for society’s rage and contempt. Nobody agrees to be bullied so the bully can really feel higher about themselves — that’s a self-serving lie bullies inform themselves. That is an externally imposed martyrdom, which negates the purpose of the train.

In The Whale, Aronofsky posits his sadism as an mental experiment, difficult viewers to search out the humanity buried below Charlie’s thick layers of fats. That’s not as benevolent of a premise as he appears to assume it’s. It proceeds from the idea {that a} 600-pound man is inherently unlovable. It’s like strolling as much as a stranger on the road and saying, “You’re an abomination, however I really like you anyway,” in step with the robust pressure of self-satisfied Christianity that the movie purports to critique. Viewers members get to stroll away pleased with themselves that they shed a couple of tears for this disgusting whale, whereas gaining no new perception into what it’s really wish to be that whale. That’s not empathy. That’s pity, buried below a thick, smothering layer of contempt.

The Whale will debut in theaters on Dec. 9.

Movie Reviews

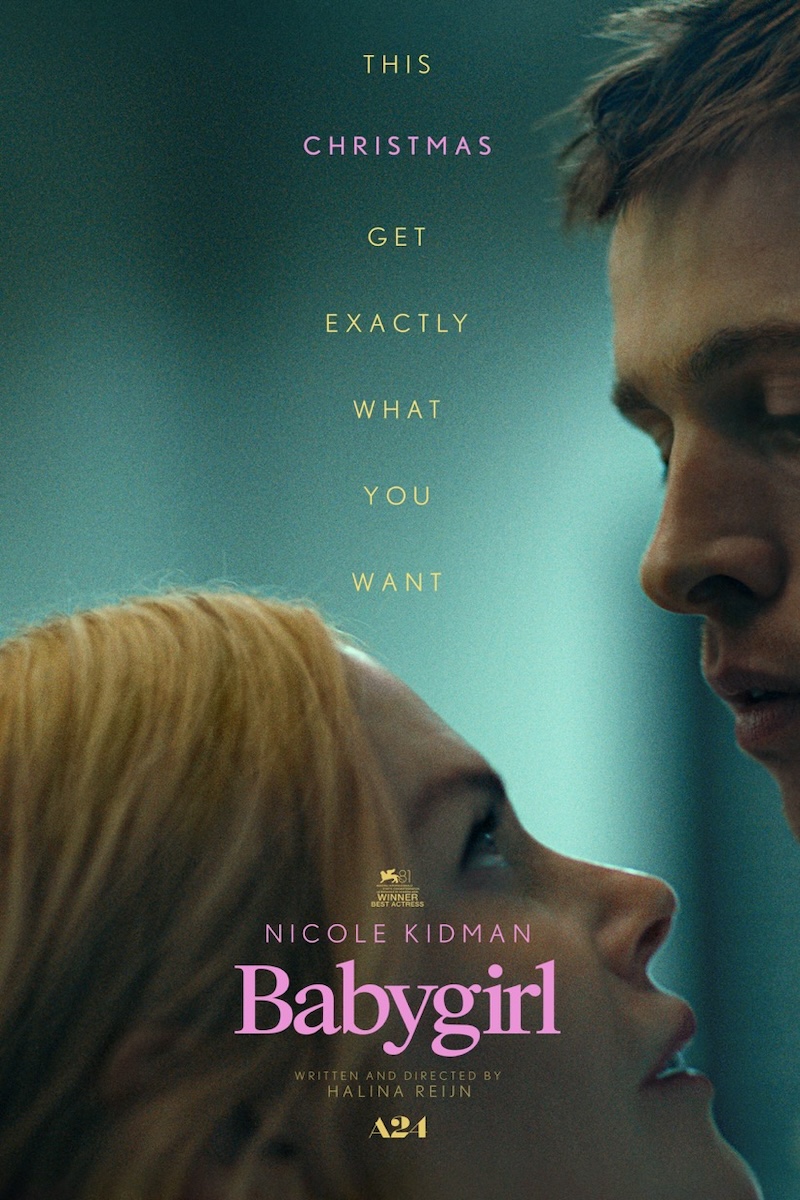

Film Review | Power Play Stationing

On the index of possible spoil alert sins one could make about the erotic thriller Babygirl, perhaps the least objectionable is that which most people already know: The film belongs to the very rare species of film literally ending with the big “O.” Nicole Kidman’s final orgasmic aria of ecstasy caps off a film which dares to tell a morally slippery tale. But for all the high points and gray zones of writer-director Halina Reijn’s intriguing film, the least ambiguous moment arrives at its climax. So to speak.

The central premise is a maze-like anatomy of an affair, between Kidman’s Romy Mathis, a fierce but also mid-life conflicted 50-year-old CEO of a robotics company, and a sly, handsome twenty-something intern Samuel (Harris Dickinson, who will appear at the Virtuosos Tribute at this year’s Santa Barbara International Film Festival). Sparks fly, and mutually pursued seduction ensues behind closed doors and away from the prying eyes of her family (and husband, played by Antonio Banderas).

From the outset, though, it’s apparent that nefarious sexual exploits, though those do liberally spice up the film’s real estate, are not the primary subject. It’s more a film steeped with power-play gamesmanship, emotional extortion, and assorted manipulations of class and hierarchical structures. Samuel teases a thinly veiled challenge to her early on, “I think you like to be told what to do.” She feigns shock, but soon acquiesces, and what transpires on their trail of deceptions and shifting romantic-sexual relationship includes a twist in which he demands her submission in exchange for him not sabotaging her career trajectory.

Kidman, who gives another powerful performance in Babygirl, is no stranger to roles involving frank sexuality and complications thereof. She has excelled in such fragile and vulnerable situations, especially boldly in Gus Van Sant’s brilliant To Die For (also a May/October brand dalliance story), and Stanley Kubrick’s carnally acknowledged Eyes Wide Shut. Ironically or not, she finds herself in the most tensely abusive sex play as the wife of Alexander Skarsgård in TVs Big Little Lies.

Compared to those examples, Babygirl works a disarmingly easygoing line. For all of his presumed sadistic power playing, Dickinson — who turns in a nuanced performance in an inherently complex role — is often confused and sometimes be mused in the course of his actions or schemes. In an early tryst encounter, his domination play seems improvised and peppered with self-effacing giggles, while in a later, potentially creepier hotel scene, his will to wield power morphs into his state of vulnerable, almost child-like reliance on her good graces. The oscillating power play dynamics get further complicated.

Complications and genre schematics also play into the film’s very identity, in fresh ways. Dutch director (and actress) Reijn has dealt with erotically edgy material in the past, especially with her 2019 film Instinct. But, despite its echoes and shades of Fifty Shades of Gray and 9½ Weeks, Babygirl cleverly tweaks the standard “erotic thriller” format — with its dangerous passions and calculated upward arc of body heating — into unexpected places. At times, the thriller form itself softens around the edges, and we become more aware of the gender/workplace power structures at the heart of the film’s message.

But, message-wise, Reijn is not ham-fisted or didactic in her treatment of the subject. There is always room for caressing and redirecting the impulse, in the bedroom, boardroom, and cinematic storyboarding.

See trailer here.

Movie Reviews

A Real Pain (2024) – Movie Review

A Real Pain, 2024.

Written and Directed by Jesse Eisenberg.

Starring Jesse Eisenberg, Kieran Culkin, Will Sharpe, Jennifer Grey, Kurt Egyiawan, Ellora Torchia, Liza Sadovy, and Daniel Oreskes.

SYNOPSIS:

Mismatched cousins David and Benji reunite for a tour through Poland to honor their beloved grandmother. The adventure takes a turn when the pair’s old tensions resurface against the backdrop of their family history.

At one point on the Holocaust tour in Poland, Benji (a devastatingly complex Kieran Culkin) loses his cool and freaks out. To be fair, he does this multiple times in writer/director/star Jesse Eisenberg’s achingly effective but sharply funny A Real Pain (marking his return to Sundance following up his debut feature When You Finish Saving the World), portraying a somewhat contradictory individual, tormented and lost following the death of his Jewish grandmother, seemingly the only adult who was able to successfully ground him. Part of the magic trick here is that Kieran Culkin is fully raw, vulnerable, authentic, and hilarious throughout every bit of his unexpected, brash, and sometimes uncalled-for behavior.

Traveling with his close cousin from New York to Poland to reconnect and pay respects to their grandma, Jesse Eisenberg’s David is also unsure what to expect, repeatedly calling Benji on the way to the airport as if disaster is going to strike if he doesn’t check up on him often. They also share polar opposite personalities, with David being, well, the socially awkward and nervous Jesse Eisenberg moviegoers are familiar with, whereas Benji is a directionless stoner (he has also arranged for some marijuana to be delivered to him at the hotel they will be staying at in Warsaw) who needs this trip as a form of therapy. As a married father, David takes time out of his busy life to be there for his cousin and provide support.

Being present is a huge theme in A Real Pain, but considering these cousins are also taking up a Holocaust tour before ending their vacationing week by visiting their grandmother’s home (where she lived in Poland before experiencing 1,000 incidents of luck to avoid concentration camps and flee the country), it’s also about suffering and the different baggage people bring to these situations. One minute, Benji is playful and encourages the rest of the group to pose alongside some memorials of soldiers, pretending to be medics or fighting alongside the resistance. In the next scene, he could be irritable riding first class on a train expressing that such privileged treatment feels distant from the reality of what his grandmother and others lived through.

Grouped up with a non-Jewish but friendly, well-meaning tour guide named James (Will Sharpe), Benji also points out that the nonstop barrage of facts, especially when visiting a historic cemetery, also feels cold and counterproductive to the experience. This shouldn’t be about statistics, but something that can be felt. In that same vein, David and Benji must also have difficult conversations about the past and what the latter will do in the present (there’s one revealed that, while sensitively handled, also feels like something this story doesn’t even need.) However, the actors do have charming chemistry whenever they are alone and reminiscing about the good times, which is unsurprisingly dynamite when things turn serious.

A Real Pain is historically and culturally emotional as it is personally involving, with Jesse Eisenberg noticeably evolving as a filmmaker. Here, he is confident and comfortable taking brief moments with cinematographer Michał Dymek to linger on statues, murals, and architecture or anything that might deliver a vicarious feeling that we are alongside these characters on this tour. There’s a beautiful, soft scene where buildings and landmarks are rattled off, each with a shot of what exists there now. It’s enough to make one wish the film delved even deeper into the historical context and the tour itself.

Naturally, this also elicits curiosity about what they will find when the cousins inevitably visit their grandmother’s former home. Whatever it is, we hope Benji finds healing and that the struggles would then he and David’s relationship will also feel repaired (it’s that typical notion of feeling lost when a relative no longer has time to be carefree and hang out constantly since they now have a family.) Without giving it away, David certainly tries resulting in a painfully funny, cathartic sensation. A Real Pain is a multilayered look at generational trauma with poignant and hilarious complex chemistry from its leads.

Flickering Myth Rating – Film: ★ ★ ★ ★ / Movie: ★ ★ ★ ★

Robert Kojder is a member of the Chicago Film Critics Association and the Critics Choice Association. He is also the Flickering Myth Reviews Editor. Check here for new reviews, follow my Twitter or Letterboxd, or email me at MetalGearSolid719@gmail.com

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=embed/playlist

Movie Reviews

‘How to Make Millions Before Grandma Dies’ Review: Thai Oscar Entry Is a Disarmingly Sentimental Tear-Jerker

It takes only a few strategic bars of tinkly piano score to suggest that the protagonist of How to Make Millions Before Grandma Dies (Lahn Mah) might trade his cynical motivation for selfless devotion before the end credits roll. But the unapologetic sentimentality doesn’t make this bittersweet comedy-drama any less touching or insightful in its observation of spiky family interactions when end-of-life issues and questions of inheritance cause sparks. Thailand’s submission for the international Oscar is the country’s first entry to make it onto the 15-title shortlist.

The debut feature from television and documentary director Pat Boonnitipat was a blockbuster in its domestic release, crossing borders to find similar success elsewhere in Southeast Asia and grossing an estimated $73.8 million worldwide. It’s easy to see why. Viral social media exposure that sprang from Manila theater staff handing out tissues prior to each screening and audience members posting videos of themselves in floods of tears on the way out no doubt helped.

How to Make Millions Before Grandma Dies

The Bottom Line A sweet crowd-pleaser.

Release date: Friday, Sept. 13

Cast: Putthipong Assaratanakul, Usha Seamkhum, Sanya Kunakorn, Sarinrat Thomas, Pongsatorn Jongwilas, Tontawan Tantivejakul, Duangporn Oapirat, Himawara Tajiri, Wattana Subpakit

Director: Pat Boonnitipat

Screenwriters: Thodsapon Thiptinnakorn, Pat Boonnitipat

2 hours 6 minutes

But what’s perhaps more significant is the perceptiveness and affection with which the screenplay by Thodsapon Thiptinnakorn and Boonnitipat captures a family dynamic that’s complicated and imperfect but grounded in a loving sense of intergenerational duty, even if concerns of personal benefit can get in the way. In the story, that dynamic is very specifically Asian, but the basic plot mechanics are sufficiently universal to resonate anywhere.

The theme of death is established with a welcome lightness of touch in an opening scene set on the day of the Qingming Festival, when families of Chinese origin visit the graves of their ancestors to clean the sites, scatter flowers and make ritual offerings of food and incense. The religious holiday matters most to Mengju (Usha Seamkhum), the crotchety grandmother of the title, fondly addressed as Amah by her family. She’s bossy and frequently critical of them, mostly with good reason.

Her eldest son Kiang (Sanya Kunakorn) is a financial trader whose wife and daughter chime in via video call, prompting Amah to point out that they never visit her. Her youngest son Soei (Pongsatorn Jongwilas) is a deadbeat with a gambling habit. The middle child is careworn supermarket worker Sew (Sarinrat Thomas), the most dutifully attentive of Mengju’s three children. However, the fact that Sew’s son M (Putthipong Assaratanakul, aka “Billkin”) has dropped out of college with the pipe dream of making money as a videogame streamer seems to reflect badly on Amah’s daughter.

When the old woman expresses her wish to be put to rest in a grand burial plot, the awkward responses suggest that none of her family will be volunteering to foot the substantial bill. While still at the cemetery, Mengju has a fall and is taken to hospital, where an examination reveals that she has stage 4 stomach cancer. The family decides to keep the grim news from her.

Meanwhile, M studies his savvy younger cousin Mui (Tontawan Tantivejakul) as she cares for their wealthy paternal grandfather in the final months of his life and then inherits most of his estate when the old man dies. Mui swiftly sells his house and moves into a modern high-rise apartment, where she sidelines as a sexy nurse on OnlyFans. She advises M to insinuate himself as Amah’s primary carer and get into pole position in her will, telling him he’ll stop noticing the “old person smell” after a while.

M starts turning up unannounced at his grandmother’s house in one of Bangkok’s Chinatown districts, where she makes a humble living selling congee at a local street market. Mengju is immediately suspicious of his motives, proving resistant when he tries to ingratiate himself with her, which prompts M to break the news of her cancer diagnosis.

Mengju accepts the prognosis with stoical calm and drops her objections when M moves in to take care of her, accompanying her at 5 a.m. each day to her congee stand. Even so, she’s an irascible woman who’s set in her ways and determinedly self-reliant, which makes her prickly during the next weekly family gathering, when even Kiang’s wife Pinn (Duangporn Oapirat) and daughter Rainbow (Himawara Tajiri) make a rare appearance.

It soon becomes apparent that almost everyone hopes to inherit Amah’s house, especially as her condition worsens and chemotherapy fails to produce results. Hard-working Sew (Thomas is the standout of the supporting cast) is the only one who cares for her mother altruistically. She’s more pragmatic than self-pitying when she observes, “Sons inherit money, daughters inherit cancer.”

The patriarchal imbalance and the tendency in traditional Asian families to favor sons — who carry on the family name — over daughters play out effectively both in developments with Mengju’s estate and in the grandmother’s own history.

In one lovely sequence, M takes her to visit her well-heeled older brother (Wattana Subpakit) and his family in their palatial home. It’s a cozy reunion, enlivened by the elderly siblings doing karaoke, until Mengju asks him for money to buy her funeral plot. She reveals to M that despite caring for her parents in their dotage, they left their entire estate to her brother, partly because of their low esteem for the husband they had chosen for Mengju in an arranged marriage.

The heartfelt movie is ill-served by an international title that suggests broad comedy — the original Thai title, Lahn Mah, means “Grandma’s Grandchild,” which comes much closer to capturing the story’s emotional center.

Even if Jaithep Raroengjai’s score leans into the sentiment, M’s growing fondness for Amah — and vice versa — is conveyed with a depth of feeling that steers it clear of the trap of formulaic schmaltz. Their bond slowly supplants his earlier opportunism. And surprising developments in the final act build to an affecting conclusion in which the sadness is mitigated by unexpected rewards.

Strong ensemble acting makes the family a believable unit, their differences notwithstanding. But it’s the evolving rapport between M and Amah that makes the film so captivating, played with humor and sensitivity by Assaratanakul — also a successful T-pop singer and Gucci brand ambassador, drabbed down in sloppy slacker gear for this role — and delightful newcomer Seamkhum, a natural in her first feature. The 78-year-old actress was signed to a modeling agency after being spotted on video in a dance contest for seniors and has been seen primarily in commercials.

In addition to eliciting solid work from his cast, the director imbues the movie with a vivid sense of place, working with DP Boonyanuch Kraithong to mark dividing lines of wealth in various Bangkok neighborhoods, notably the historic, traditionally Thai Chinese Talat Phlu community where Mengju lives.

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoThese are the top 7 issues facing the struggling restaurant industry in 2025

-

Culture7 days ago

Culture7 days agoThe 25 worst losses in college football history, including Baylor’s 2024 entry at Colorado

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoThe top out-of-contract players available as free transfers: Kimmich, De Bruyne, Van Dijk…

-

Politics5 days ago

Politics5 days agoNew Orleans attacker had 'remote detonator' for explosives in French Quarter, Biden says

-

Politics5 days ago

Politics5 days agoCarter's judicial picks reshaped the federal bench across the country

-

Politics3 days ago

Politics3 days agoWho Are the Recipients of the Presidential Medal of Freedom?

-

Health2 days ago

Health2 days agoOzempic ‘microdosing’ is the new weight-loss trend: Should you try it?

-

World7 days ago

World7 days agoIvory Coast says French troops to leave country after decades