Entertainment

Camille Claudel's hand, not her trauma, is at the center of a magnificent Getty Museum show

A notable similarity marks a subcategory of once woefully under-recognized female artists of the past. Their resolute endurance of trauma is proposed as a primary reason to reassess their work today.

At age 18, Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1653) survived the abusive manipulations of rape by the painter Agostino Tassi, a colleague in her studio. Public humiliation followed the private ordeal when she courageously took his assault to trial.

Frida Kahlo (1907-54) endured decades of grueling pain after a bus she was riding in — also at age 18 — smashed into a trolley and forced a long metal rod to rip through her midsection. The vehicular wreck caused internal injuries that would plague her throughout her life.

Then there is Camille Claudel (1864-1943). Her trauma came later, when mental and emotional deterioration led to her confinement in a psychiatric institution, far from the Paris studio of Auguste Rodin, in which her own brilliant work as a sculptor had blossomed. The cause for the internment was said to be paranoid psychosis. She was 48 and remained hospitalized for 30 years, the remainder of her life.

“Camille Claudel,” a fascinating exhibition at the J. Paul Getty Museum, unwinds the traumatic tale, and in the process refocuses the story in important ways. In the popular telling, Claudel is to France what Gentileschi was to Italy and Kahlo to Mexico: the overlooked artist as victim — a casualty not just once, but twice. The active personal trauma experienced in life was joined by passive negligence after death from the culture at large.

Camille Claudel, “Crouching Woman,” about 1884-85, patinated plaster

(J. Paul Getty Museum)

The welcome revival of interest in the paintings and sculptures of Gentileschi, Kahlo and Claudel since the 1970s and ’80s was led by second-wave feminists, and it represented an effort to transform victimhood into survivorship in the cultural sphere. Which sounds good, but has a catch. The narrative focus tends to linger on the artist, not the art.

Biography, framed by dramatic events, often overwhelms the paintings and sculptures, which are admired for the reductive ways in which they illuminate the artist’s tumultuous life. It can lead to travesty, such as a current Gentileschi exhibition at the Palazzo Ducale in Genoa, Italy, reported to feature what some critics have witheringly described as a “rape room” — a darkened chamber with a bloodied bed in the center, surrounded by projections of Gentileschi’s often gory paintings.

It’s no accident that multiple movies and plays have been produced about Gentileschi, Kahlo and Claudel, with various incidents vividly sensationalized to court pop culture success. A lead actress Oscar nomination, for example, deservedly went to Isabelle Adjani for the 1989 film “Camille Claudel,” and then to Salma Hayek for the 2002 movie “Frida.” The talented actors were given lots of cinematic scenery on which to chew.

In the case of Claudel, a subtle but opportune correction of the narrative arrives in the new museum show.

Curators Anne-Lise Desmas at the Getty and Emerson Bowyer at the Art Institute of Chicago, where the show was seen last fall, make no bones about articulating the sculptor’s very real travails. Outlined in the superb and detailed catalog are the artist’s sometimes difficult personal affair with Rodin, 24 years her senior and a commanding figure in the art life of late 19th century Paris; a rapidly industrializing society in flux, for artists as for others, that nonetheless saw exceptionally high fences erected around a woman’s potential for success as a sculptor; and internal family issues that left Claudel without much immediate personal support when she very much needed it.

“This biographical miasma,” the curators write in the catalog introduction, “has tended to obscure — or even excise — the sculptor’s art and agency.” Those subjects get put in appropriate context by an enlightening exhibition.

Camille Claudel, “The Age of Maturity,” 1890-99, bronze

(Christopher Knight / Los Angeles Times)

Fifty-eight sculptures have been assembled, including works in clay, plaster, marble and bronze. They include the major 1890-99 ensemble “The Age of Maturity,” a large, three-figure allegory of aging that unfolds in multiple bronze sections, in which youth gives way to the inevitability of old age and death. There’s a stunning and compact portrait-bust of Rodin, in which the focused concentration of his life-size head seems to rise up out of a tumult below, represented by his lengthy, swirling, thickly tangled beard. And, for contrast, we get Rodin’s winsome portrait of Claudel, the lowered gaze of her intensely alert but ethereal head emerging from a hefty block of chiseled white marble.

At first, her portrait appears unfinished, but that’s a misperception. Rodin titled his sculpture “Thought.” Perhaps he recognized what emerges from encounters with Claudel’s art. Repeatedly, her figures stoop, crouch, look down or away, resulting in a concentrated bodily sense of intense interiority. Experiential subjectivity forms the essence of her human forms.

In a beautiful installation, many works are smartly shown on a pedestal positioned atop a circular base, which wordlessly leads a viewer all the way around — ideal for an art that needs to be seen in four dimensions of space and time. Revealing labels are sometimes nicely tucked away, as in one on the far side of “The Age of Maturity” informing that the baroque flourish of drapery billowing at the apex is actually a precise facsimile, the original bronze piece currently undergoing conservation back in Paris.

The number of works is relatively modest — understandably so, given the comparative brevity of her career (barely two decades, while Rodin’s was more than twice as long) and her need to devote years as a studio assistant. They range from a remarkably adept terracotta portrait bust of an elderly household member, “Old Helen,” made when Claudel was 21, to a complicated state commission for a mythological subject in bronze, “Wounded Niobid,” dated 1907, near the end of a tough career that had left her nearly destitute.

Claudel was born into a solidly middle-class family in 1864, daughter of a registrar of deeds in a small medieval town 60 miles from Paris. Her mother bore four children, one of whom — Paul — would go on to become a well-known poet and an influential diplomat posted to China, Brazil, the United States and elsewhere. With her father regularly being transferred to various provincial towns, Claudel and her siblings settled in Paris with their mother in 1881. There she began her serious study of sculpture, met Rodin during student critiques and within three years was employed in his studio.

Auguste Rodin gave the title “Thought” to his 1895-1901 marble portrait of Camille Claudel

(Christopher Knight / Los Angeles Times)

Rodin relied on his assistant’s formal skills, especially Claudel’s talents with the difficult task of successfully rendering expressive hands and feet. She’s credited with work on major commissions, including the monumental bronze sculptural group “The Gates of Hell” — the one with the “Thinker” poised on the doorway’s head jamb like an inquisitive crow, puzzling over humanity’s infernal chaos on its way to eternal doom — and, most important, “The Burghers of Calais.” (Check out the animated hands of those sacrificial citizens!) Perhaps the show’s most riveting small work is a little bronze study of a hand, just 10 inches wide, no doubt informed by Claudel’s careful scrutiny of her own. A curved index finger rises up from the rest like a speaker separating from a crowd and preparing to expound.

The exhibition was inspired by Getty and Art Institute of Chicago acquisitions in recent years. (Only 10 Claudel sculptures are in American museums, according to press materials.) Chicago’s is a plaster portrait bust of Camille’s brother Paul, made when he was a teenager and layered in thin glazes of paint to create an illusion of the patina on an ancient Roman bronze head. The Getty’s is one of the show’s knockouts.

A sculpture as fresh and contemporary as anything you’ll find in a gallery crawl today, the dark bronze “Torso of a Crouching Woman,” about three feet tall, is a headless, armless figure surely inspired by a famous Greek example of Aphrodite emerging from the bath, which the artist would have known from prowls in the Louvre Museum. Feet squarely planted, center of gravity low, Claudel’s version rests firmly on the ground while twisting in space. The movement pulls skin taut over the ribs, spine and musculature of her back, enlivening the subject’s tactile sensuality.

With one notable exception, the sliced off body parts allude to the fragmentary quality of the ancient original, which has lost its head and arms from time’s vicissitudes. The exception is the missing left knee. Gone is most of the leg.

Camille Claudel, “Torso of a Crouching Woman,” modeled circa 1884-85, bronze cast about 1913

(The J. Paul Getty Museum)

Cut off just above the ankle all the way to mid-thigh, the omission isn’t found in the classical Greek original or its many Roman copies, where the leg is a prominent protrusion. The vivid erasure also seems different from just being overkill in a nod to history by a young sculptor earnestly figuring things out. (Claudel is thought to have made the sculpture when she was about 20.) Instead, the radical cut reads as a determined compositional move. You imagine the jutting knee was there in her clay model, thought better of, then given a chop.

The result further exposes the torso in its most vulnerable feminine places, while accelerating the figure’s spatial turn. Claudel’s visceral cut invigorates the form — a seeming contradiction for a removal to accomplish, but one that is as modern as will be found in any contemporaneous bather painted in oil or drawn in pastel by Edgar Degas.

It’s also hard to imagine Rodin doing something like that. Claudel surely benefited from her artistic relationship with the revered sculptor. But he benefited from it as well, modeling some of his work on her inventive forms, plus using all those eloquent hands and feet. A good bit of the scholarship around Claudel in the last few decades has been directed at correcting attributions to him for sculptures she made but did not sign.

A modern cliché has it that an artist must suffer to achieve true success in their art, and Claudel, like Gentileschi and Kahlo, surely did. But for female artists throughout history, the marvelous Getty exhibition handily demonstrates that there’s much more to it than only surviving trauma. Everyone needs to labor to get through the day. A powerful artist needs to do more, and Claudel does.

‘Camille Claudel’

Where: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1200 Getty Center Drive, Brentwood

When: Through July 21; closed Mondays

Info: (310) 440-7300, www.getty.edu

Entertainment

Barbra Streisand clarifies Ozempic query to Melissa McCarthy: 'Wanted to pay her a compliment'

When it comes to writing music, Barbra Streisand can have a way with words. Instagram comments? Not so much.

The legendary “Funny Girl” and “A Star Is Born” entertainer, 82, shed light on her latest Instagram activity after she went viral Monday for asking Melissa McCarthy if she was using a popular weight-loss medication. In a statement shared to her Instagram stories on Tuesday, Streisand clarified she wanted to praise “The Little Mermaid” star’s look from her and choreographer Matthew Bourne’s appearances at the Center Theatre Group’s annual gala over the weekend.

On Monday afternoon, McCarthy, 53, had shared photos of her and Bourne’s gala glam. “Pastels only to honor the incredible @matthewbourne13 at the @ctgla gala last night with this fella @adamshankman!! Thiiiiis much closer to my dream of dancing on stage 💃🏻💚🩷,” McCarthy captioned her photos.

The duo earned praise from Hollywood peers, including actors Glenn Close and Mariska Hargitay who both commented, “gorgeous.”

“These lewks are yummy,” Oscar winner Octavia Spencer commented on McCarthy’s photo.

“Absolutely stunning. thank you so much for honoring @matthewbourne13 at the gala with us. We love you!!!,” Center Theatre Group responded.

However, hours after McCarthy shared her photos, Streisand commented, “Give him my regards did you take Ozempic?,” according to multiple screenshots shared on social media.

Ozempic, also known as semaglutide, is an injectable diabetes medication that has in recent years become Hollywood’s go-to quick weight-loss drug. Amy Schumer, Sharon Osbourne, Chelsea Handler and Tracy Morgan are among the celebrities who have been public about using Ozempic.

“OMG,” the singer began her Tuesday missive. Streisand explained she opened up Instagram to look at photos of flowers from her recent birthday celebration.

“Below them was a photo of my friend Melissa McCarthy who I sang with on my Encore album,” she wrote. “She looked fantastic! I just wanted to pay her a compliment.”

Streisand’s nonchalant comment on Monday quickly garnered divided reactions on social media. In the comments section of McCarthy’s post, followers wrote, that the EGOT (Emmy, Grammy, Oscar, Tony) winner “should be ashamed of herself!”

“Babs. No, honey. Just no,” one user responded to Streisand’s comment, which has since been deleted on Instagram.

On X (formerly Twitter), some users laughed at Streisand’s offhand comment, and others gave the Broadway icon the benefit of the doubt. “Omg somebody please teach Barbra Streisand how to send a DM,” wrote one user.

“Omg. I think she thought this was a DM?” echoed another X user.

“Nah, she meant that…and knew right where she posted it,” responded a fourth user.

The “Yentl” star added in her Tuesday statement: “I forgot the world is reading!”

In a brief encounter with TMZ published Tuesday afternoon, McCarthy brushed off Streisand’s comment. “I think Barbra is a treasure and I love her,” the Oscar-nominated “Bridesmaids” star said in a video.

For years, McCarthy has been open about her appearance, speaking publicly about experiences with fat-shaming and how she has come to accept herself.

“Somewhere in my 30s, I was like ‘I’m okay with who I am.’ And if someone wasn’t thrilled with that, that’s okay too,” she told People in 2023. “At some point I was like, ‘They’re not all going to like you.’ You have to learn that the hard way, but it’s a good [lesson].”

Movie Reviews

The Fall Guy movie review: Ryan Gosling & Emily Blunt starrer is an ode to 90s massy action-comedies

)

Ryan Gosling & Emily Blunt’s The Fall Guy is directed by David Leitch

read more

Cast: Ryan Gosling, Emily Blunt, Aaron Taylor-Johnson, Hannah Waddingham, Winston Duke

Director: David Leitch

Since the inception of movies (especially of the action genre), audiences have showered praises on hardcore action films, which have given them an adrenaline rush with mind-boggling action stunts and breathtaking sequences. And the reason behind that are the unsung heroes – the stunt doubles, who take risks of their lives to give us that experience. Ryan Gosling & Emily Blunt starrer The Fall Guy is a tribute to all those stuntmen.

The movie starts with Colt Seavers (Ryan Gosling) stunt double of action star Tom Ryder (Aaron Taylor-Johnson) talking about the greatness of stuntmen while walking on the set after a stunt. While the stunt seems perfect, Tom tells Colt to go for another take as he feels in the given shot, the audience will identify that the person, who has performed the stunt is Colt because of his jawline.

While Colt gets ready for another take, he faces an accident while performing it and gets off the radar from the entertainment industry and works as a valet at a family place. 18 months later, he gets a call from Tom’s producer Gail (Hannah Waddingham), who tells him to come back to the place and do what he loves. While his response is always negative, she reveals that Jody (Emily Blunt) once a steady cam operator, who had an affair with Colt, is making her directorial debut with a biggie titled Metalstorm featuring Tom and wants him for doing stunts.

Colt agrees to come on the set and while we see his rekindling of love with Jody with cute and funny banters, the reason to call him is tricky and vicious. Gail tells Colt that Tom has been missing for quite a few days and he needs to find him out. When he enters the actor’s room, he finds another stunt double of Tom dead in the bathtub.

He panics and while trying to inform everything about the incident to Gail, we see some goons attacking him and later becoming one of the prime suspects of the murder. Well, so many questions in your mind, right? And the answer to all these you will find on the big screen while watching

The Fall Guy

, which is a fun roller-coaster with delightful action sequences.

Director David Leitch has made a film, which has its heart at the right place and makes sure to give us ample whistle-worthy moments through its entertaining screenplay, which has filmy references, AI as well as Deepfake technology.

Talking about the performances, Ryan Gosling is a one-man show and rules the screen with his enigmatic charisma. Emily is amazing as Jodi and her chemistry with Ryan is superb. Aaron Taylor-Johnson and Hannah Waddingham as Tom and Gail are simply perfect. Winston Duke steals the show with his bang-on comic timing.

On the whole, The Fall Guy is a delightful action comedy, which reminds you of massy Bollywood films from the 90s minus the technology.

Rating: 3 (out of 5 stars)

The Fall Guy will release on 3rd May

Entertainment

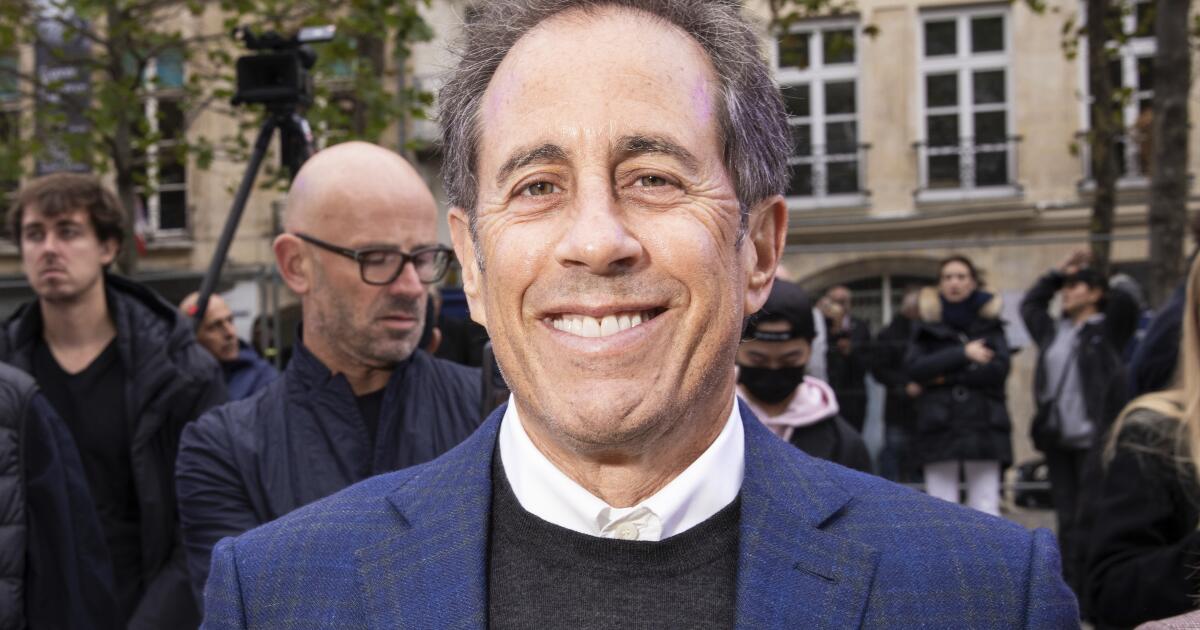

Jerry Seinfeld says ‘the extreme left and P.C. crap’ are hurting TV comedy

Ahead of his stint at the Hollywood Bowl and the release of his Netflix comedy about Pop-Tarts’ origin this week, Jerry Seinfeld reflected on the “Seinfeld” storylines that wouldn’t be aired today and other ways “the extreme left” is influencing comedy.

In an interview with the New Yorker, the comedian said some of his jokes from the ‘90s would be subject to “cancel culture” today. Of one plot from “Seinfeld” involving Kramer’s business venture to have “homeless people pull rickshaws” because “they’re outside anyway,” the comedian asked, “Do you think I could get that episode on the air today?”

When the New Yorker‘s David Remnick said he couldn’t watch “Unfrosted” without thinking about the Israel-Hamas war and other humanitarian issues across the world, Seinfeld dismissed the idea that comedy could or should be affected or diluted by world events.

“Nothing really affects comedy. People always need it,” he said. “They need it so badly and they don’t get it.”

Seinfeld went on to reflect on the lack of comfort sitcoms like “The Mary Tyler Moore Show,” “MASH,” “Cheers” and “All in the Family,” which guaranteed audiences had something funny to watch. He said he doesn’t think that’s the case anymore.

“This is the result of the extreme left and P.C. crap, and people worrying so much about offending other people,” Seinfeld continued.

He noted that if audiences are looking for edgier comedy, they have to turn to stand-up comics because they “are not policed by anyone,” adding that they know when they’re “off track.”

When Remnick, who had previously asked Seinfeld about his longtime collaborator Larry David and the recent finale of “Curb Your Enthusiasm,” wondered how David could pull off provocative, irreverent comedy today, Seinfeld said he had been “grandfathered” in.

David, who began his career in the ‘70s, can break the “rules” in place today, according to Seinfeld, because he had been making comedy for decades before those rules existed. Seinfeld said he doesn’t think a younger person could start out today making television shows like “Seinfeld” or “Curb,” even though audiences seek out boundary-pushing content on HBO and its competitors, as opposed to network sitcoms.

“HBO knows that’s what people come here for, but they’re not smart enough to figure out, ‘How do we do this now? Do we take the heat, or just not be funny?’ And what they’ve decided to be is, ‘Well, we’re not going to do comedies anymore.’”

The comedian said he thinks younger stand-up comedians are pushing the envelope, like he and his peers did before, and commended Nate Bargatze, Ronny Chieng, Brian Simpson, Mark Normand and Sam Morril on their work.

Seinfeld is also continuing his own stand-up gigs, including his performances at the Hollywood Bowl on Wednesday and Thursday with Bargatze, Jim Gaffigan and Sebastian Maniscalco for Netflix Is a Joke Fest.

Beyond his stand-up, he made his directorial debut with “Unfrosted,” a film that follows the race to make Pop-Tarts. He also wrote, starred in and produced the film, which premieres Friday on Netflix.

-

Education1 week ago

Education1 week agoVideo: Dozens of Yale Students Arrested as Campus Protests Spread

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoEU sanctions extremist Israeli settlers over violence in the West Bank

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoDemocrats hold major 2024 advantage as House Republicans face further chaos, division

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoFetterman hammers 'a–hole' anti-Israel protesters, slams own party for response to Iranian attack: 'Crazy'

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoPeriod poverty still a problem within the EU despite tax breaks

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoA battle over 100 words: Judge tentatively siding with California AG over students' gender identification

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoShort Film Review: Wooden Toilet (2023) by Zuni Rinpoche

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoUniversal Studios Tram Crashes, 15 Injured, 1 Critical

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24931307/236791_Apple_iPhone_15_and_15_Plus_review_DSeifert_0010.jpg)