Education

More College Athletes Are Trekking to Ironman

KAILUA-KONA, Hawaii — Evan Roshak had simply settled into his writing class at Portland State College when he seen a classmate sporting shorts on a frigid winter day and sporting a particular pink tattoo on his proper ankle.

“Are you an Ironman?” Roshak requested his classmate Will Watson.

Sure. In reality, Watson had gotten the tattoo after qualifying for this yr’s Ironman World Championship in Hawaii. And since Roshak had Ironman aspirations, too, he started to coach with Watson, and in the end certified this summer season.

The 2 Oregon college students are a part of an atypically giant contingent of undergraduate college students who’re right here for triathlon’s pinnacle race. From Clemson to Dartmouth, and Loyola Chicago to the College of Utah, at the least a dozen women and men from N.C.A.A. colleges are taking as much as per week off from lessons, and juggling midterm exams and papers, to compete in what triathletes merely name Kona.

The surge will be defined, partially, by the coronavirus pandemic, as these athletes, hypercompetitive by nature, embraced lengthy runs, indoor and outside bike rides, and countless pool laps to keep off isolation and set new targets.

However extra broadly, triathlon is having a second amongst younger athletes. Greater than 40 N.C.A.A. colleges now supply ladies’s triathlon as a varsity sport, up from only a handful lower than a decade in the past, with the most recent being the College of Arizona. And with school athletes now free to become profitable from preparations that capitalize on their renown (generally known as identify, picture and likeness offers), competing in excessive sports activities like triathlon is extra financially sensible.

Small surprise, then, that Ironman, hoping to drum up curiosity amongst school sports activities followers, simply introduced a 70.3-mile race in State School, Pa., in July 2023, which can finish on the 50-yard line of Penn State’s Beaver Stadium.

“The standard sense is that you simply don’t do these races while you’re younger and your physique continues to be creating, and it’s an outdated retired dad’s sport as a result of they’ve the time and the monetary freedom to do these items,” stated Roshak, 22, a senior historical past main. “However I feel there’s a brand new understanding of what younger folks can do.”

The Ironman totals 140.6 miles — 2.4 miles of swimming, 112 miles of bicycling and 26.2 miles of working — and should be accomplished in 17 hours. That’s greater than double the swim leg, and greater than 4 instances the bike and run legs, of the Olympic triathlon.

Kona is definitely the second championship to be held in 2022. The 2021 version of the race, which was postponed by the pandemic, was held in Could in St. George, Utah — the primary time the championship was staged outdoors Hawaii. The 2020 race was canceled.

To herald its return to Hawaii, Ironman, which is owned by Advance Publications, invited Chris Nikic, the primary particular person with Down syndrome to finish an Ironman, and Sebastien Bellin, a former Belgian skilled basketball participant who virtually misplaced his legs in the course of the 2016 Brussels terror assault, amongst others, to compete.

As for the 82 skilled triathletes vying for the $125,000 first-place prize, this yr’s race marked the primary time the boys’s and girls’s races had been held on separate days for the reason that first Hawaiian Iron Man Triathlon in 1978.

In an upset, Chelsea Sodaro of Mill Valley, Calif., a former All-American runner on the College of California, Berkeley, captured the ladies’s race on Thursday in 8 hours 33 minutes 46 seconds. Daniela Ryf of Switzerland, the reigning champion, completed eighth, half an hour behind Sodaro.

The lads’s race started at daybreak Saturday, and the leaders had been anticipated to complete by midafternoon. Kristian Blummenfelt of Norway, the defending champion and Olympic gold medalist, was the prohibitive favourite. One of many sentimental decisions, although, was Tim O’Donnell, the 2019 runner-up, who was competing in his first race since he practically died from a coronary heart assault, midrace, in March 2021.

Greater than 5,000 folks registered for Kona, with practically half coming from Europe. And whereas the common competitor’s age was 45, round 100 folks — a large contingent — got here from the youngest age group, 18 to 24.

Since 2011, the variety of ladies ages 18 to 24 registering for Kona has elevated by 68 %, and the variety of males by 56 %.

“There may be some magic right here,” stated Sarah Sawaya, a 19-year-old sophomore on the College of Mississippi, who was the youngest American participant. “I’m so glad I received to expertise it.”

A lot of the American school college students had competed in both swimming or cross-country in highschool. A number of, like Sawaya, have mother and father or siblings who’ve executed marathons or triathlons.

Two had been achieved skiers in Oregon (slopestyle) and Utah (large mountain). One other had performed highschool golf for 4 years outdoors of Chicago.

One frequent thread, although, was a fascination with pushing the boundaries of endurance, at youthful and youthful ages, thanks partially to the success of the Norwegians in long-distance working.

“The Norwegians are dominating,” Roshak stated. “They’re younger, they usually’re rewriting the rule guide by way of what your physique must be.”

Peyton Thompson, 20, the youngest male qualifier, stated he marveled on the Norwegians’ obsession with information evaluation, science and vitamin.

Thompson had as soon as been a promising level guard in northern Florida, taking part in on prime youth basketball groups. However after sustaining critical knee accidents, he gave up his dream of taking part in school hoops and enrolled at Duke with pre-med aspirations.

Then the pandemic hit. And though he lived on campus whereas taking on-line lessons, he was unable to affix a slew of golf equipment, as he had initially hoped. So voilà, triathlon.

“I needed to learn to swim,” stated Thompson, a neuroscience main.

Thompson is one among three Ironman college students from the Analysis Triangle. Andrew Buchanan, from Redondo Seashore, Calif., is a senior on the College of North Carolina. Corinne Mouw, a local of Pittsgrove, N.J., is a senior at North Carolina State, and energetic within the college’s triathlon membership.

Despite the fact that Mouw’s classmates had been despatched house in March 2020 due to the pandemic, she stayed in Raleigh, working in a co-op job that was a part of her mechanical engineering main. However everybody stayed linked via Strava, a web based exercise-tracking device.

“Despite the fact that I couldn’t see my buddies, I might see them doing their exercises,” she stated.

The price of competing will be prohibitive and simply quantity to $15,000 yearly, Roshak estimated, for a coach, a bicycle, separate fits for land and water, race registration charges and extra. Sponsorships with firms can defray the prices via clothes and gear reductions, however many triathletes lean on their households and work part-time jobs.

Funds have all the time loomed giant for Frasier Williamson, 24, of Kaysville, Utah, who received a scholarship to run cross-country for Weber State.

Following a two-year Mormon mission to the Philippines, Williamson, now a junior, was coaching together with his school teammates and getting again in form. However he realized he wouldn’t get a scholarship because the athletic division tightened its spending in the course of the pandemic.

“Both I’d have an primarily full-time job to run for school and get one other full-time job to pay for school, or I might learn the writing on the wall and check out one thing else,” he stated.

Jordan Ambrose, 20, virtually dedicated to swim for McKendree College in Illinois as a sprinter. However after she was identified with thoracic outlet syndrome, she stopped swimming and enrolled on the College of Southern Indiana, close to her house in Mt. Vernon, Ind.

Itching for exercise in the course of the pandemic, she started coaching for marathons together with her cousin. Solely when she realized that she might swim lengthy distances with out ache did triathlons emerge as an choice.

After she completed her first triathlon, Ambrose was contacted by Trine College, in northeastern Indiana, which received the N.C.A.A. Division III triathlon title in 2021. Are you curious about transferring?

Ambrose was intrigued however declined, partially as a result of she needed to affix Southern Indiana’s swim workforce in its debut season.

“I’ll now give attention to swim,” she stated, after ending the Ironman in 13 hours 12 minutes 9 seconds. “The workforce, the aggressive ambiance — I adore it all.”

Trine is one among 14 N.C.A.A. Division III colleges that take part in dash triathlons within the fall. The races embrace a 750-meter swim, 20-kilometer bike experience and 5-kilometer run. There are 15 colleges in Division II and 12 in Division I that take part, headlined by Arizona State, which has received 5 straight nationwide titles. Greater than 300 ladies from 24 international locations are on rosters.

By 2024, triathlon might grow to be an official N.C.A.A. championship sport. And shortly, the USA Triathlon Basis will launch a collective, to be financed by donors, that will pay N.C.A.A. triathletes via identify, picture and likeness offers to advertise the game on social media, stated Tim Yount, chief sport growth officer of USA Triathlon.

Throughout Thursday’s Ironman race in sizzling and muggy circumstances, there have been moments when Sawaya, the Mississippi scholar, felt that she couldn’t proceed. She wobbled on her bike, buffeted by the Huge Island’s fierce crosswinds. Her ft had been coated in blisters.

“On the run, I used to be falling asleep,” added Sawaya, a sophomore learning biomedical engineering.

However she soldiered on, thanking the volunteers donning canary-colored T-shirts who lined the course and befriending different triathletes. As night time fell, one man who ran alongside her for 10 miles advised her he had a daughter her age.

So when she completed in 15 hours 34 minutes 19 seconds, beaded by a light-weight rain, she raised her arms and beamed. It was 10:19 p.m.

“So many tales,” she stated. “All of the ache, all of the ache — it was price it.”

She had little time to relaxation, although, as a result of she needed to put together for a web based natural chemistry examination at 9 a.m.

Education

Video: Johnson Condemns Pro-Palestinian Protests at Columbia University

new video loaded: Johnson Condemns Pro-Palestinian Protests at Columbia University

transcript

transcript

Johnson Condemns Pro-Palestinian Protests at Columbia University

House Speaker Mike Johnson delivered brief remarks at Columbia University on Wednesday, demanding White House action and invoking the possibility of bringing in the National Guard to quell the pro-Palestinian protests. Students interrupted his speech with jeers.

-

“A growing number of students have chanted in support of terrorists. They have chased down Jewish students. They have mocked them and reviled them. They have shouted racial epithets. They have screamed at those who bear the Star of David.” [Crowd chanting] “We can’t hear you.” [clapping] We can’t hear you.” “Enjoy your free speech. My message to the students inside the encampment is get — go back to class and stop the nonsense. My intention is to call President Biden after we leave here and share with him what we have seen with our own two eyes and demand that he take action. There is executive authority that would be appropriate. If this is not contained quickly, and if these threats and intimidation are not stopped, there is an appropriate time for the National Guard. We have to bring order to these campuses. We cannot allow this to happen around the country.”

Recent episodes in U.S. & Politics

Education

Video: Dozens of Yale Students Arrested as Campus Protests Spread

new video loaded: Dozens of Yale Students Arrested as Campus Protests Spread

transcript

transcript

Dozens of Yale Students Arrested as Campus Protests Spread

The police arrested students at a pro-Palestinian protest encampment at Yale University, days after more than 100 student demonstrators were arrested on the campus of Columbia University.

-

Crowd: “Free, free Palestine.” [chanting] “We will not stop, we will not rest. Disclose, divest.” “We will not stop, we will not rest. Disclose, divest.”

Recent episodes in Israel-Hamas War

Education

Why School Absences Have ‘Exploded’ Almost Everywhere

In Anchorage, affluent families set off on ski trips and other lengthy vacations, with the assumption that their children can keep up with schoolwork online.

In a working-class pocket of Michigan, school administrators have tried almost everything, including pajama day, to boost student attendance.

And across the country, students with heightened anxiety are opting to stay home rather than face the classroom.

In the four years since the pandemic closed schools, U.S. education has struggled to recover on a number of fronts, from learning loss, to enrollment, to student behavior.

But perhaps no issue has been as stubborn and pervasive as a sharp increase in student absenteeism, a problem that cuts across demographics and has continued long after schools reopened.

Nationally, an estimated 26 percent of public school students were considered chronically absent last school year, up from 15 percent before the pandemic, according to the most recent data, from 40 states and Washington, D.C., compiled by the conservative-leaning American Enterprise Institute. Chronic absence is typically defined as missing at least 10 percent of the school year, or about 18 days, for any reason.

Increase in chronic absenteeism, 2019–23

By local child poverty rates

By length of school closures By district racial makeup

Source: Upshot analysis of data from Nat Malkus, American Enterprise Institute. Districts are grouped into highest, middle and lowest third.

The increases have occurred in districts big and small, and across income and race. For districts in wealthier areas, chronic absenteeism rates have about doubled, to 19 percent in the 2022-23 school year from 10 percent before the pandemic, a New York Times analysis of the data found.

Poor communities, which started with elevated rates of student absenteeism, are facing an even bigger crisis: Around 32 percent of students in the poorest districts were chronically absent in the 2022-23 school year, up from 19 percent before the pandemic.

Even districts that reopened quickly during the pandemic, in fall 2020, have seen vast increases.

“The problem got worse for everybody in the same proportional way,” said Nat Malkus, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, who collected and studied the data.

Victoria, Texas reopened schools in August 2020, earlier than many other districts. Even so, student absenteeism in the district has doubled.

Kaylee Greenlee for The New York Times

The trends suggest that something fundamental has shifted in American childhood and the culture of school, in ways that may be long lasting. What was once a deeply ingrained habit — wake up, catch the bus, report to class — is now something far more tenuous.

“Our relationship with school became optional,” said Katie Rosanbalm, a psychologist and associate research professor with the Center for Child and Family Policy at Duke University.

The habit of daily attendance — and many families’ trust — was severed when schools shuttered in spring 2020. Even after schools reopened, things hardly snapped back to normal. Districts offered remote options, required Covid-19 quarantines and relaxed policies around attendance and grading.

Today, student absenteeism is a leading factor hindering the nation’s recovery from pandemic learning losses, educational experts say. Students can’t learn if they aren’t in school. And a rotating cast of absent classmates can negatively affect the achievement of even students who do show up, because teachers must slow down and adjust their approach to keep everyone on track.

“If we don’t address the absenteeism, then all is naught,” said Adam Clark, the superintendent of Mt. Diablo Unified, a socioeconomically and racially diverse district of 29,000 students in Northern California, where he said absenteeism has “exploded” to about 25 percent of students. That’s up from 12 percent before the pandemic.

U.S. students, overall, are not caught up from their pandemic losses. Absenteeism is one key reason.

Kaylee Greenlee for The New York Times

Why Students Are Missing School

Schools everywhere are scrambling to improve attendance, but the new calculus among families is complex and multifaceted.

At South Anchorage High School in Anchorage, where students are largely white and middle-to-upper income, some families now go on ski trips during the school year, or take advantage of off-peak travel deals to vacation for two weeks in Hawaii, said Sara Miller, a counselor at the school.

For a smaller number of students at the school who qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, the reasons are different, and more intractable. They often have to stay home to care for younger siblings, Ms. Miller said. On days they miss the bus, their parents are busy working or do not have a car to take them to school.

And because teachers are still expected to post class work online, often nothing more than a skeleton version of an assignment, families incorrectly think students are keeping up, Ms. Miller said.

Sara Miller, a counselor at South Anchorage High School for 20 years, now sees more absences from students across the socioeconomic spectrum.

Ash Adams for The New York Times

Across the country, students are staying home when sick, not only with Covid-19, but also with more routine colds and viruses.

And more students are struggling with their mental health, one reason for increased absenteeism in Mason, Ohio, an affluent suburb of Cincinnati, said Tracey Carson, a district spokeswoman. Because many parents can work remotely, their children can also stay home.

For Ashley Cooper, 31, of San Marcos, Texas, the pandemic fractured her trust in an education system that she said left her daughter to learn online, with little support, and then expected her to perform on grade level upon her return. Her daughter, who fell behind in math, has struggled with anxiety ever since, she said.

“There have been days where she’s been absolutely in tears — ‘Can’t do it. Mom, I don’t want to go,’” said Ms. Cooper, who has worked with the nonprofit Communities in Schools to improve her children’s school attendance. But she added, “as a mom, I feel like it’s OK to have a mental health day, to say, ‘I hear you and I listen. You are important.’”

Experts say missing school is both a symptom of pandemic-related challenges, and also a cause. Students who are behind academically may not want to attend, but being absent sets them further back. Anxious students may avoid school, but hiding out can fuel their anxiety.

And schools have also seen a rise in discipline problems since the pandemic, an issue intertwined with absenteeism.

Dr. Rosanbalm, the Duke psychologist, said both absenteeism and behavioral outbursts are examples of the human stress response, now playing out en masse in schools: fight (verbal or physical aggression) or flight (absenteeism).

“If kids are not here, they are not forming relationships,” said Quintin Shepherd, the superintendent in Victoria, Texas.

Kaylee Greenlee for The New York Times

Quintin Shepherd, the superintendent in Victoria, Texas, first put his focus on student behavior, which he described as a “fire in the kitchen” after schools reopened in August 2020.

The district, which serves a mostly low-income and Hispanic student body of around 13,000, found success with a one-on-one coaching program that teaches coping strategies to the most disruptive students. In some cases, students went from having 20 classroom outbursts per year to fewer than five, Dr. Shepherd said.

But chronic absenteeism is yet to be conquered. About 30 percent of students are chronically absent this year, roughly double the rate before the pandemic.

Dr. Shepherd, who originally hoped student absenteeism would improve naturally with time, has begun to think that it is, in fact, at the root of many issues.

“If kids are not here, they are not forming relationships,” he said. “If they are not forming relationships, we should expect there will be behavior and discipline issues. If they are not here, they will not be academically learning and they will struggle. If they struggle with their coursework, you can expect violent behaviors.”

Teacher absences have also increased since the pandemic, and student absences mean less certainty about which friends and classmates will be there. That can lead to more absenteeism, said Michael A. Gottfried, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education. His research has found that when 10 percent of a student’s classmates are absent on a given day, that student is more likely to be absent the following day.

Absent classmates can have a negative impact on the achievement and attendance of even the students who do show up. Ash Adams for The New York Times

Is This the New Normal?

In many ways, the challenge facing schools is one felt more broadly in American society: Have the cultural shifts from the pandemic become permanent?

In the work force, U.S. employees are still working from home at a rate that has remained largely unchanged since late 2022. Companies have managed to “put the genie back in the bottle” to some extent by requiring a return to office a few days a week, said Nicholas Bloom, an economist at Stanford University who studies remote work. But hybrid office culture, he said, appears here to stay.

Some wonder whether it is time for schools to be more pragmatic.

Lakisha Young, the chief executive of the Oakland REACH, a parent advocacy group that works with low-income families in California, suggested a rigorous online option that students could use in emergencies, such as when a student misses the bus or has to care for a family member. “The goal should be, how do I ensure this kid is educated?” she said.

Relationships with adults at school and other classmates are crucial for attendance.

Kaylee Greenlee for The New York Times

In the corporate world, companies have found some success appealing to a sense of social responsibility, where colleagues rely on each other to show up on the agreed-upon days.

A similar dynamic may be at play in schools, where experts say strong relationships are critical for attendance.

There is a sense of: “If I don’t show up, would people even miss the fact that I’m not there?” said Charlene M. Russell-Tucker, the commissioner of education in Connecticut.

In her state, a home visit program has yielded positive results, in part by working with families to address the specific reasons a student is missing school, but also by establishing a relationship with a caring adult. Other efforts — such as sending text messages or postcards to parents informing them of the number of accumulated absences — can also be effective.

Regina Murff has worked to re-establish the daily habit of school attendance for her sons, who are 6 and 12.

Sylvia Jarrus for The New York Times

In Ypsilanti, Mich., outside of Ann Arbor, a home visit helped Regina Murff, 44, feel less alone when she was struggling to get her children to school each morning.

After working at a nursing home during the pandemic, and later losing her sister to Covid-19, she said, there were days she found it difficult to get out of bed. Ms. Murff was also more willing to keep her children home when they were sick, for fear of accidentally spreading the virus.

But after a visit from her school district, and starting therapy herself, she has settled into a new routine. She helps her sons, 6 and 12, set out their outfits at night and she wakes up at 6 a.m. to ensure they get on the bus. If they are sick, she said, she knows to call the absence into school. “I’ve done a huge turnaround in my life,” she said.

But bringing about meaningful change for large numbers of students remains slow, difficult work.

Nationally, about 26 percent of students were considered chronically absent last school year, up from 15 percent before the pandemic.

Kaylee Greenlee for The New York Times

The Ypsilanti school district has tried a bit of everything, said the superintendent, Alena Zachery-Ross. In addition to door knocks, officials are looking for ways to make school more appealing for the district’s 3,800 students, including more than 80 percent who qualify for free or reduced-price lunch. They held themed dress-up days — ’70s day, pajama day — and gave away warm clothes after noticing a dip in attendance during winter months.

“We wondered, is it because you don’t have a coat, you don’t have boots?” said Dr. Zachery-Ross.

Still, absenteeism overall remains higher than it was before the pandemic. “We haven’t seen an answer,” she said.

-

Education1 week ago

Education1 week agoVideo: Dozens of Yale Students Arrested as Campus Protests Spread

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoShipping firms plead for UN help amid escalating Middle East conflict

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoEU sanctions extremist Israeli settlers over violence in the West Bank

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week ago'Nothing more backwards' than US funding Ukraine border security but not our own, conservatives say

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoDemocrats hold major 2024 advantage as House Republicans face further chaos, division

-

Politics1 week ago

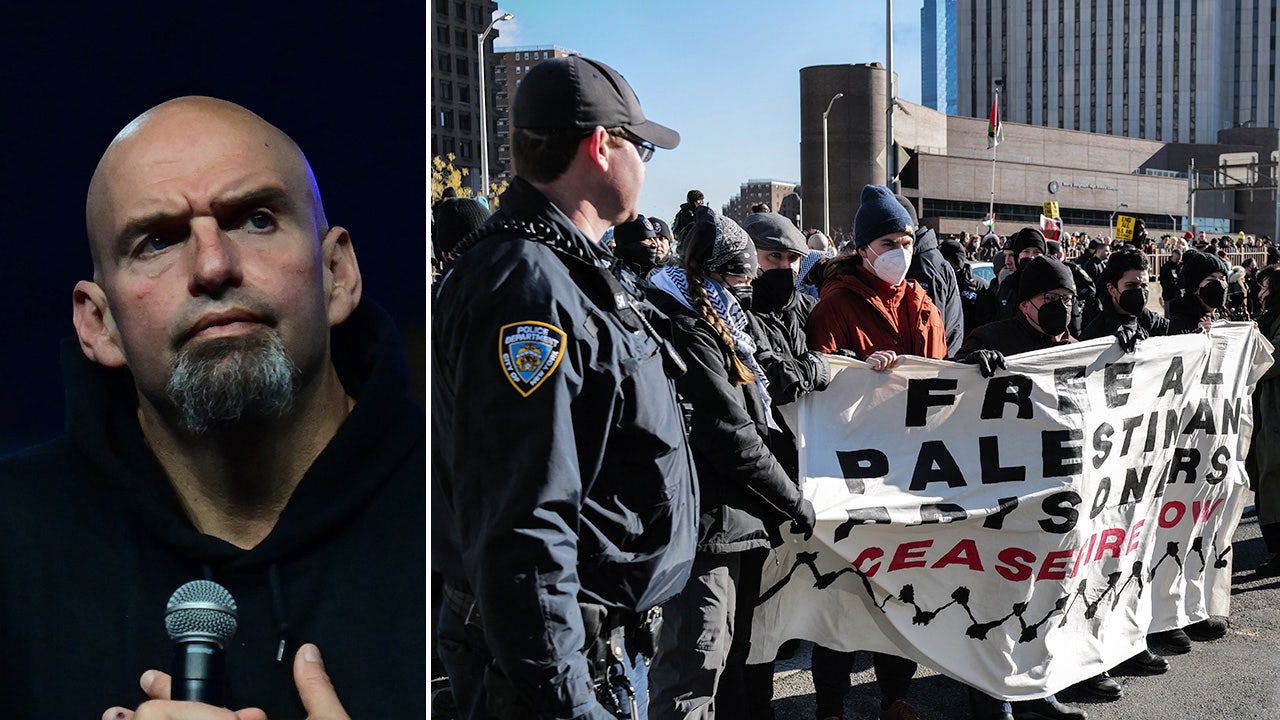

Politics1 week agoFetterman hammers 'a–hole' anti-Israel protesters, slams own party for response to Iranian attack: 'Crazy'

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoPeriod poverty still a problem within the EU despite tax breaks

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoA battle over 100 words: Judge tentatively siding with California AG over students' gender identification