Culture

Trailing Michel Houellebecq From the Bedroom to the Courtroom

On Saturday night, an eclectic art crowd was gathering outside an industrial garage in Amsterdam East, where Michel Houellebecq, the celebrated French author, was set to speak.

Houellebecq had on May 24 released “A Few Months of My Life,” a new book describing a tumultuous period from October 2022 to March 2023 when he collaborated with a Dutch art collective called KIRAC. Together, they worked on a film, shooting scenes that show the married 67-year-old author making out with young women.

Although Houellebecq had consented to making the film, he later changed his mind and tried to back out. Beginning in February, he brought court cases in France and the Netherlands to stop the movie from being shown. Last month, an Amsterdam judge upheld Houellebecq’s complaint and granted him the right to see a final cut of any re-edited film four weeks before release, giving him a chance to file another action if he doesn’t like what he sees.

In “A Few Months of My Life,” a 94-page autobiographical work, Houellebecq digs deep into his hatred for KIRAC. He names the group’s leader, Stefan Ruitenbeek, only once, describing him as a “pseudo-artist” and “a cockroach with a human face.” Female KIRAC members are referred to as “the sow” and “the turkey.”

According to the organizer of Saturday’s event, Tarik Sadouma, Houellebecq had not come to Amsterdam to promote his new book, but to talk about his work generally. As a condition of his participation, Houellebecq asked Sadouma to bar Ruitenbeek and his cohorts from the event.

Yet just as the audience took its seats inside, Ruitenbeek burst through the door, dressed as a giant brown cockroach, with bobbing antennae and a furry cape. He was trailed by KIRAC members, one wearing a false pig snout, another filming the whole thing.

“I’m here!” cried Ruitenbeek, taking the stage, to a mixture of jeering and cheers. “I’m the cockroach!”

A woman taking tickets tried to wrangle the camera from the cameraman and Sadouma shouted for the intruders to leave. Eventually, Ruitenbeek — pleading, “No violence!” — left with his entourage.

This was the latest episode in an ongoing, surrealistic conflict between KIRAC, a fringe art group that posts its films on YouTube, and Houellebecq, one of the world’s most famous authors.

Was it a performance? A marketing stunt? Or part of a genuine cultural feud? Who could really tell?

KIRAC, an acronym for Keeping It Real Art Critics, is often described as an art collective, but its creative center is Ruitenbeek and Kate Sinha, a writer who is also Ruitenbeek’s life partner. They make films that at first appear to be documentaries, or possibly mockumentaries, typically set in the art world. In them, the boundaries between reality and fiction are often blurred, narratives sometimes conflict and onscreen characters can appear to be playing a game with the truth.

It is also often difficult to discern KIRAC’s political views. In one of its films, the Dutch architect and curator Rem Koolhaas is criticized as “macho” and “patriarchal.” In another, KIRAC seems to decry diversity efforts, arguing that the artist Zanele Muholi was given a retrospective at the Stedelijk Museum, in Amsterdam, “only because she is from South Africa, Black and lesbian.” (Muholi now uses they/them pronouns and identifies as nonbinary.)

Seen as provocateurs or pranksters, and sometimes art world trolls, KIRAC’s members often deliver critical monologues directly to the camera, usually in the form of articulate academic analysis from Sinha, or mocking insults from Ruitenbeek.

“In the broadest sense, we’re just trying to make great films, intellectual entertainment,” Sinha said. “I think we are primarily artists, interested in the object we make, which is always the film.”

In a joint interview, Ruitenbeek and Sinha said they developed the concept for the Houellebecq film with the author and shot 600 hours of footage of him, with his contractual consent. Houellebecq only objected when they put together a two-minute trailer for the work in progress, according to Ruitenbeek and Sinha.

In that clip, Ruitenbeek explains that a “honey trip,” or sex holiday, that Houellebecq had planned in Morocco had been canceled because the author feared being kidnapped by Muslim extremists. (Houellebecq has a long history of making critical statements about Islam, and some readers have found Islamophobic sentiments in his books.)

“His wife had spent an entire month arranging prostitutes from Paris, and now everything was falling apart,” Ruitenbeek says in the trailer, in voice-over. He then suggests that there are plenty of young Dutch women in Amsterdam who would have “sex with a famous writer out of curiosity,” and invites the author to visit.

In a French court, Houellebecq argued that the trailer violated his privacy and damaged his image. He asked the court to make KIRAC pull the trailer from all online platforms, remove any mention of his wife arranging prostitutes and pay her damages. The court rejected Houellebecq’s case.

Later, in the Dutch court, Houellebecq argued that KIRAC had violated contract law, and misled him so that he ended up “in a different film than the one originally intended,” according to his Dutch lawyer, Jacqueline Schaap. An appeal judge in that case found for Houellebecq.

The film is still unfinished and continues to evolve, Ruitenbeek said. After Houellebecq left the project, KIRAC filmed in and around the court proceedings, as well as shooting other moments, such as Saturday night’s cockroach show.

Ruitenbeek said he was now rethinking the material, and a final cut may not come for months.

“We started off this project in an open-minded attitude toward each other; we took each other as artists,” Sinha said of the collaboration with Houellebecq. “It feels like he backpedaled and put on a different coat.”

Houellebecq last week agreed to an interview for this article, but pulled out after learning that he would not be shown his quotes before publication. (At the event in Amsterdam, he again declined to comment, claiming that he did not speak English, although he speaks it in the KIRAC film.)

Ruitenbeek’s over-the-top voice-overs and willingness to play a goofball suggest that KIRAC is going for humor. But, often, the subjects of its films don’t find them funny.

“They point fingers at others, but carve out a safe space for themselves’,” said the artist Renzo Martens, who was the focus of an unflattering movie. “From this safe space they are brave enough to cut into other people’s flesh.”

Three Dutch institutions that KIRAC has lambasted — the Stedelijk Museum, the Van Abbe Museum and the Kunstmuseum, in The Hague — declined to comment for this article.

Thijs Lijster, a senior lecturer on the philosophy of art and culture at the University of Groningen, said that there is “something threatening in their ways of going about their work. They have a style of filming, and approaching and talking to people, which is, in a way, rather hostile.”

It is not just KIRAC’s targeting of artists and institutions that has been controversial. Over time, its films have evolved to enter the realm of social commentary, drawing ire from across the political spectrum.

Some viewers saw the group’s 19-minute film “Who’s Afraid of Harvey Weinstein?,” in which Sinha speaks about sexual power dynamics between the American film producer and his rape victims, as dismissive of the #MeToo movement.

A leading art school in Amsterdam, the Gerrit Rietveld Academy, canceled a KIRAC screening after dozens of complaints from students, former students and teachers about statements in the group’s films that they found sexist and racist. The Weinstein movie was championed on a right-wing populist Dutch blog, Geen Stijl. Suddenly, KIRAC became a magnet for conservative followers.

Although Ruitenbeek and Sinha said their personal politics are progressive, KIRAC didn’t disavow the attention, and instead produced a film called “Honeypot.” For that, the group convinced a conservative Dutch philosopher and activist, Sid Lukkassen, to have sex on camera with a left-wing student. The idea was to see if the intimate act would somehow bridge a political gap.

More backlash ensued. When an Amsterdam arts center called De Balie screened “Honeypot,” a feminist collective submitted a petition with more than 1,000 signatures that called the film “a glorification of sexual violence.” The petition’s signers also included the right-wing Dutch politician Paul Cliteur and some of his followers.

“It was interesting that these two sides teamed up against the film for opposite reasons,” said Yoeri Albrecht, De Balie’s director, who did not cancel the event. “I’ve never seen that happen in the more than a decade that I’ve been organizing events here.”

The ambiguity around the group’s motivations only feeds the interest in KIRAC’s work. Many who have been following the Houellebecq affair are unsure whether it’s real or a postmodern KIRAC fiction.

“Everyone is wondering, are they playing a game together?” said Simon Delobel, a curator who teaches at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, in Ghent, Belgium, where he was introduced to the group’s work by his students. KIRAC and Houellebecq were surely “well aware that it can be interpreted as a stunt,” he added.

Yet Ruitenbeek and Sinha both said their clash with the author was no stunt. They don’t want to be in court with Houellebecq, whom they both described as “a genius.” They just want to be in conversation with him, Sinha said.

Ruitenbeek added that when he showed up at Houellebecq’s talk on Saturday, he thought there was a small chance that everyone would laugh and give each other hugs. He was “very happy the day he went to get the cockroach suit,” Sinha said. “After all these intimidating court cases,” she added, “we were back on our own territory again: making art.”

Léontine Gallois contributed reporting from Paris.

Culture

Book Review: ‘Hunger Like a Thirst,’ by Besha Rodell

HUNGER LIKE A THIRST: From Food Stamps to Fine Dining, a Restaurant Critic Finds Her Place at the Table, by Besha Rodell

Consider the food critic’s memoir. An author inevitably faces the threat of proportional imbalance: a glut of one (the tantalizing range of delicacies eaten) and want of the other (the nonprofessional life lived). And in this age of publicly documenting one’s every bite, it’s easier than ever to forget that to simply have dined, no matter how extravagantly, is not enough to make one interesting, or a story worth telling.

Fortunately, the life of Beshaleba River Puffin Rodell has been as unusual as her name. In fact, as she relays in the author’s note that opens “Hunger Like a Thirst,” a high school boyfriend believed she’d “made up her entire life story,” starting with her elaborate moniker.

Born in Australia on a farm called Narnia, she is the daughter of hippies. Her father, “a man of many lives and vocations,” was in his religious scholar phase, whence Beshaleba, an amalgamation of two Bible names, cometh.

Rodell’s mother returned to her native United States, with her children and new husband, when Besha was 14. Within the first 20-plus years of her life, she had bounced back and forth repeatedly between the two continents and, within the U.S., between multiple states. “‘I’m not from here’ is at the core of who I am,” she writes.

It’s also at the core of her work as a restaurant critic, and what, she convincingly argues, distinguishes her writing from that of many contemporaries. She has the distanced perspective of a foreigner, but also lacks the privilege of her counterparts, who are often male and frequently moneyed. “For better or for worse, this is the life that I have,” she writes. “The one in which a lady who can’t pay her utility bills can nonetheless go eat a big steak and drink martinis.” This, she believes, is her advantage: “Dining out was never something I took for granted.”

It started back in Narnia on the ninth birthday of her childhood best friend, who invited Rodell to tag along at a celebratory dinner at the town’s fanciest restaurant. Rodell was struck, not by the food, but by “the mesmerizing, intense luxury of it all.” From then on, despite or perhaps because of the financial stress that remains a constant in her life, she became committed to chasing that particular brand of enchantment, “the specific opulence of a very good restaurant. I never connected this longing to the goal of attaining wealth; in fact, it was the pantomiming that appealed.”

To become a writer who gets poorly compensated to dine at those very good restaurants required working multiple jobs, including, in her early days, at restaurants, while simultaneously taking on unpaid labor as an intern and attending classes.

Things didn’t get much easier once Rodell became a full-time critic and she achieved the milestones associated with industry success. She took over for Atlanta’s most-read restaurant reviewer, then for the Pulitzer-winning Jonathan Gold at L.A. Weekly. She was nominated for multiple James Beard Awards and won one for an article on the legacy of the 40-ounce bottle of malt liquor.

After moving back to Australia with her husband and son, she was hired to review restaurants for The New York Times’s Australia bureau, before becoming the global dining critic for both Food & Wine and Travel & Leisure. Juxtaposed against the jet-setting and meals taken at the world’s most rarefied restaurants is her “real” life, the one where she can barely make rent or afford groceries.

It turns out her outsider status has also left her well positioned to excavate the history of restaurant criticism and the role of those who have practiced it. She relays this with remarkable clarity and explains how it’s shaped her own work. (To illustrate how she’s put her own philosophy into practice, she includes examples of her writing.) It’s this analysis that renders Rodell’s book an essential read for anyone who’s interested in cultural criticism.

Packing all of the above into one book is a tall order, and if Rodell’s has a flaw, it’s in its structure. The moving parts can seem disjointed and, although the intention behind the structure is a meaningful one, the execution feels forced.

As she explains in her epilogue, she used the table of contents from Anthony Bourdain’s “Kitchen Confidential” as inspiration for her own. Titled “Tony,” the section is dedicated to him. But, however genuine the sentiment, to end on a man whose shadow looms so large detracts from her own story. (If anything, Rodell’s approach feels more aligned with the work of the Gen X feminist Liz Phair, whose lyric the book’s title borrows.)

It certainly shouldn’t deter anyone from reading it. Rodell’s memoir is a singular accomplishment. And if this publication were to hire her as a dining critic in New York, there would be no complaints from this reader.

HUNGER LIKE A THIRST: From Food Stamps to Fine Dining, a Restaurant Critic Finds Her Place at the Table | By Besha Rodell | Celadon | 272 pp. | $28.99

Culture

Book Review: ‘Original Sin,’ by Jake Tapper and Alex Thompson

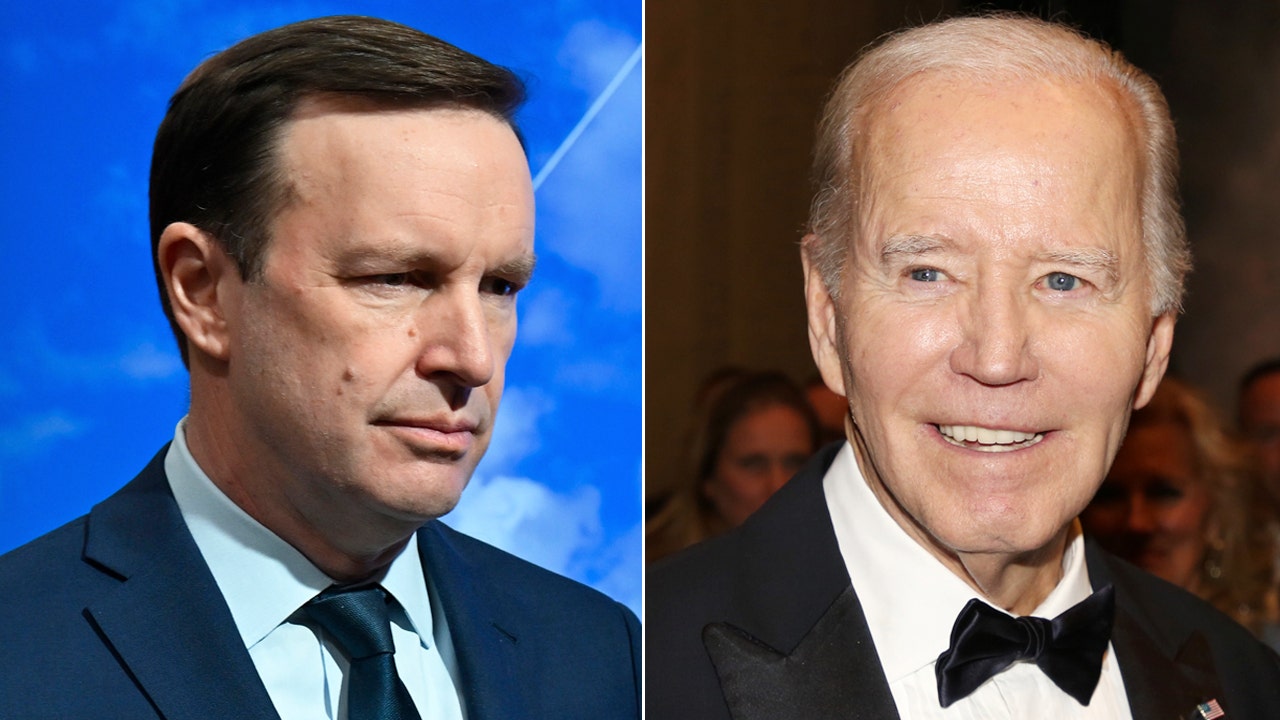

ORIGINAL SIN: President Biden’s Decline, Its Cover-Up, and His Disastrous Choice to Run Again, by Jake Tapper and Alex Thompson

In Christian theology, original sin begins with Adam and Eve eating the forbidden fruit from the tree of knowledge. But Jake Tapper and Alex Thompson’s “Original Sin” chronicles a different fall from grace. The cover image is a black-and-white portrait of Joe Biden with a pair of hands clamped over his eyes. The biblical story is about the danger of innocent curiosity; the story in this new book is about the danger of willful ignorance.

“The original sin of Election 2024 was Biden’s decision to run for re-election — followed by aggressive efforts to hide his cognitive diminishment,” Tapper and Thompson write. On the evening of June 27, 2024, Democratic voters watched the first presidential debate in amazement and horror: A red-faced Donald Trump let loose a barrage of audacious whoppers while Biden, slack-jawed and pale, struggled to string together intelligible rebuttals.

Trump’s debate performance was of a piece with his rallies, a jumble of nonsensical digressions and wild claims. But for many Americans, the extent of Biden’s frailty came as a shock. Most of the president’s appearances had, by then, become tightly controlled affairs. For at least a year and a half, Biden’s aides had been scrambling to accommodate an octogenarian president who was becoming increasingly exhausted and confused. According to “Original Sin,” which makes pointed use of the word “cover-up” in the subtitle, alarmed donors and pols who sought the lowdown on Biden’s cognitive state were kept in the dark. Others had daily evidence of Biden’s decline but didn’t want to believe it.

Tapper is an anchor for CNN (and also served as a moderator for the presidential debate); Thompson is a national political correspondent for Axios. In an authors’ note, they explain that they interviewed approximately 200 people, including high-level insiders, “some of whom may never acknowledge speaking to us but all of whom know the truth within these pages.”

The result is a damning, step-by-step account of how the people closest to a stubborn, aging president enabled his quixotic resolve to run for a second term. The authors trace the deluge of trouble that flowed from Biden’s original sin: the sidelining of Vice President Kamala Harris; the attacks on journalists (like Thompson) who deigned to report on worries about Biden’s apparent fatigue and mental state; an American public lacking clear communication from the president and left to twist in the wind. “It was an abomination,” one source told the authors. “He stole an election from the Democratic Party; he stole it from the American people.”

This blistering charge is attributed to “a prominent Democratic strategist” who also “publicly defended Biden.” In “Original Sin,” the reasons given for saying nice things in public about the president are legion. Some Democrats, especially those who didn’t see the president that often, relied on his surrogates for reassurance about his condition (“He’s fine, he’s fine, he’s fine”); others were wary of giving ammunition to the Trump campaign, warning that he was an existential threat to the country. Tapper and Thompson are scornful of such rationales: “For those who tried to justify the behavior described here because of the threat of a second Trump term, those fears should have shocked them into reality, not away from it.”

Biden announced that he would be running for re-election in April 2023; he had turned 80 the previous November and was already the oldest president in history. Over his long life, he had been through a lot: the death of his wife and daughter in a car accident in 1972; two aneurysm surgeries in 1988; the death of his son Beau in 2015; the seemingly endless trouble kicked up by his son Hunter, a recovering addict whose legal troubles included being under investigation by the Justice Department.

Yet Biden always bounced back. The fact that he defied the naysayers and beat the odds to win the 2020 election was, for him and his close circle of family and advisers, a sign that he was special — and persistently underestimated. They maintained “a near-religious faith in Biden’s ability to rise again,” the authors write. “And as with any theology, skepticism was forbidden.”

In 2019, when Biden announced a presidential run, he was 76. It was still a time when “Good Biden was far more present than Old Biden.” By 2023, the authors suggest, that ratio had reversed. Some of his decline was hard to distinguish from what they call “the Bidenness,” which included his longtime reputation for gaffes, meandering stories and a habit of forgetting staffers’ names.

But people who didn’t see Biden on a daily basis were increasingly taken aback when they finally laid eyes on him. They would remark on how his once booming voice had become a whisper, how his confident stride had become a shuffle. An aghast congressman recalls being reminded of his father, who had Alzheimer’s; another thought of his father, too, who died of Parkinson’s.

The people closest to Biden landed on some techniques to handle (or disguise) what was happening: restricting urgent business to the hours between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m.; instructing his writers to keep his speeches brief so that he didn’t have to spend too much time on his feet; having him use the short stairs to Air Force One. When making videos, his aides sometimes filmed “in slow motion to blur the reality of how slowly he actually walked.” By late 2023, his staff was pushing as much of his schedule as they could to midday.

When White House aides weren’t practicing fastidious stage management, they seemed to be sticking their heads in the sand. According to a forthcoming book by Josh Dawsey, Tyler Pager and Isaac Arnsdorf, Biden’s aides decided against his taking a cognitive test in early 2024. Tapper and Thompson quote a physician who served as a consultant to the White House Medical Unit for the last four administrations and expressed his dismay at the idea of withholding such information: “If there’s no diagnosis, there’s nothing to disclose.”

Just how much of this rigmarole was desperate rationalization versus deliberate scheming is never entirely clear. Tapper and Thompson identify two main groups that closed ranks around Biden: his family and a group of close aides known internally as “the Politburo” that included his longtime strategist Mike Donilon and his counselor Steve Ricchetti. The family encouraged Biden’s view of himself as a historic figure. The Politburo was too politically hard-nosed for that. Instead, its members pointed to Biden’s record in office and the competent people around him. The napping, the whispering, the shuffling — all that stuff had merely to do with the “performative” parts of the job.

Tapper and Thompson vehemently disagree. They offer a gracious portrait of Robert Hur, the special counsel who investigated Biden’s handling of classified materials and in his February 2024 report famously described the president as a “sympathetic, well-meaning, elderly man with a poor memory.” Biden and his team were incensed and tried “to slime Hur as an unprofessional right-wing hack,” but the authors defend his notorious line. They emphasize that it is incumbent upon a special counsel to spell out how the subject of an investigation would probably appear to a jury — and that what Hur wrote about Biden was true.

Of course, in an election like 2024, when the differences between the candidates are so stark and the stakes are so high, nearly every scrap of information gets viewed through the lens of “Will it help my team win?” Even competently administered policy could not compensate for a woeful inability to communicate with the American people. In a democracy, this is a tragedy — especially if you believe, as Biden did, that a second Trump term would put the very existence of that democracy in peril.

Earlier this month, in what looks like an attempt to get ahead of the book’s publication, Biden went on “The View” to say that he accepts some responsibility for Trump’s victory: “I was in charge.” But he was dismissive about reports of any cognitive decline. In “Original Sin,” Tapper and Thompson describe him waking up the morning after the 2024 election thinking that if only he had stayed in the race, he would have won. “That’s what the polls suggested, he would say again and again,” the authors write. There was just one problem with his reasoning: “His pollsters told us that no such polls existed.”

ORIGINAL SIN: President Biden’s Decline, Its Cover-Up, and His Disastrous Choice to Run Again | By Jake Tapper and Alex Thompson | Penguin Press | 332 pp. | $32

Culture

Book Review: ‘Death Is Our Business,’ by John Lechner; ‘Putin’s Sledgehammer,’ by Candace Rondeaux

Western complacency, meanwhile, stoked Russian imperial ambition. Though rich in resources, Rondeaux notes, Russia still relies on the rest of the world to fuel its war machine. Wagner’s operations in Africa burgeoned around the same time as their Syrian operation. In 2016, the French president François Hollande “semi-jokingly” suggested that the Central African Republic’s president go to the Russians for help putting down rebel groups. “We actually used Hollande’s statement,” Dmitri Syty, one of the brains behind Wagner’s operation there, tells Lechner.

“Death Is Our Business” provides powerful descriptions of the lives that were upended by the mercenary deployments. Wagner is accused of massacring hundreds of civilians in Mali in 2022, and of carrying out mass killings alongside local militias in the Central African Republic. “Their behavior mirrored the armed groups they ousted,” Lechner writes. As a Central African civil society activist whispers to Lechner, “Russia is no different” from the sub-Saharan country’s former colonial power, France.

Both books are particularly interesting when they turn their focus toward Europe and the United States. In Rondeaux’s words, the trans-Atlantic alliance does not “have a game plan for countering Russia’s growing influence across Africa.” Lechner, who was detained while reporting his book by officials from Mali’s pro-Russian government, is even more critical. He notes that, whatever Wagner produced profit-wise, the sum would have “paled in comparison to the $1 billion the E.U. paid Russia each month for oil and gas.”

And, while Wagner was an effective boogeyman, mercenaries of all stripes have proliferated across the map of this century’s conflicts, from the Democratic Republic of Congo to Yemen. “The West was happy to leverage Wagner as shorthand for all the evils of a war economy,” Lechner writes. “But the reality is that the world is filled with Prigozhins.”

Lechner is right. When Wagner fell, others rose in its stead, although they were kept on a tighter leash by Russian military intelligence. In Ukraine, prisoners are still being used in combat and Russia maintains a tight lid on its casualty figures. Even if the war in Ukraine ends soon, as President Trump has promised, Moscow’s mercenaries will still be at work dividing their African cake. Prigozhin may be dead, but his hammer is still a tool: It doesn’t matter if he’s around to swing it or not.

DEATH IS OUR BUSINESS: Russian Mercenaries and the New Era of Private Warfare | By John Lechner | Bloomsbury | 261 pp. | $29.99

PUTIN’S SLEDGEHAMMER: The Wagner Group and Russia’s Collapse Into Mercenary Chaos | By Candace Rondeaux | PublicAffairs | 442 pp. | $32

-

Austin, TX6 days ago

Austin, TX6 days agoBest Austin Salads – 15 Food Places For Good Greens!

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoBe careful what you read about an Elden Ring movie

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoNetflix is removing Black Mirror: Bandersnatch

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoThe Take: Can India and Pakistan avoid a fourth war over Kashmir?

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoReincarnated by A.I., Arizona Man Forgives His Killer at Sentencing

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoJefferson Griffin Concedes Defeat in N.C. Supreme Court Race

-

Health1 week ago

Health1 week agoN.I.H. Bans New Funding From U.S. Scientists to Partners Abroad

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoWho is the new Pope Leo XIV and what are his views?