Culture

How Does a Man Become an Island?

AN ISLAND, by Karen Jennings

It will not be a positive factor, however it’s guess: In the event you write a piece of fiction that forgoes a redemptive arc or glad ending, and also you additionally occur to be a lady, eventually you’ll get requested the query that’s not not like being advised to smile by passers-by on a sidewalk: Why darkness?

Why, mild sister, did you not select the trail of sunshine?

The South African writer Karen Jennings’s novel “An Island,” her first to be printed in america, is about an outdated man named Samuel dwelling in isolation as a lighthouse keeper after a hardscrabble life in an unspecified nation someplace within the south of the continent. The novel articulates a superbly easy and real reply to the above query and neatly heads it off on the move — historical past, brother. Historical past.

Samuel grows up poor after his household is violently evicted from its land by rampaging, scorched-earth colonists, and is compelled to resort to begging to scrape collectively a sustenance within the metropolis to which they flee. His father then fights for independence and within the course of is completely disabled. Regardless of the motion’s victory, the postcolonial corruptions of energy end up to provide new bosses who, regardless of a cynical veneer of populism, are a lot the identical because the outdated.

Although he doesn’t go as far as to kill, a younger Samuel will get swept up right into a damaging “culling” of foreigners within the metropolis — a xenophobic bloodbath incited by a common who will quickly be a dictator — and his participation turns into one in all many sources of deep disgrace. Ultimately, following his peripatetic, halfhearted involvement in one other revolutionary gesture, so in poor health conceived it finally ends up amounting to little greater than a minor riot, Samuel spends 23 years in jail.

When he’s launched in the end, the world outdoors has been reworked past recognition (not that he’d navigated it with any confidence to start with). His estranged sister and her youngsters deal with him with contempt and cruelty, whereas the one lady he’s ever cared for romantically by no means held him in excessive esteem — and, a long time later, is now an getting old prostitute who barely remembers his identify.

So he takes refuge on a harbor island, the place he exists in a form of exhausted, solitary respite, performing his duties to the lighthouse, elevating chickens, tending a small backyard and sustaining the stone wall he’s constructed to demarcate his lonely area, defending it from incursions from the skin. When the occasional physique of a refugee washes up on the shore, he provides it into the wall.

However when the novel opens, a type of washed-up our bodies seems to not be a corpse in spite of everything. By now a 70-year-old hermit who’s more and more paranoid and delusional, Samuel spends the period of the story contending with the alarming presence of this dwelling newcomer — a person who, not like so many others, treats him with a belief and even a kindness he can’t understand or hope to return.

“An Island,” which was on the longlist for Britain’s Booker Prize in 2021, is superbly and sparingly constructed. The sections within the narrative current are a tactile evocation of the pure and materials world round these two males; and within the flashbacks to Samuel’s coming-of-age after which torturous captivity, Jennings renders a gritty and stripped-down portrait of the grim household dynamics and social situations that made him who he’s.

As he struggles in previous and current to dig himself out of the psychological ruts of poverty and desperation, ethical polarities come to be reversed. “What may he have been if he had been braver,” Samuel used to ask himself as he walked across the metropolis at night time, “if he hadn’t been afraid of homicide?”Each within the metropolis and on the island, he lives within the distorting shadow of a cowardice he first witnessed in his father — a denial of the fact of political betrayal, a disintegration of beliefs. His father, too brittle and compromised to confront the proof that his personal sacrifice has resulted in the identical abuses of energy he as soon as fought to get rid of, sees the naked tin partitions of despotism and stubbornly calls them gold.

In Jennings’s arms, this antihero’s enmeshment in his personal failures has a textured credibility that’s exhausting to look away from. At each flip he disappoints himself, in addition to others; at each flip these disappointments settle atop one another just like the our bodies he buries beneath the stones.

“An Island” is a personality research with the cross-cultural resilience of a fable, like Kobo Abe’s “The Lady within the Dunes,” working on private and symbolic planes on the similar time.

How does a person flip into an island? Oppression and shortage and disempowerment, sure; the bafflement of attempting to type coherent selfhood with out sturdy function fashions, actually; and on the base, at all times, an absence of empathy and of affection.

No plot abstract can do justice to a narrative woven this fastidiously, whose power lies in its deliberate pacing and sharp dispensation of element. Samuel is as actual as a shaking hand.

AN ISLAND, by Karen Jennings | 210 pp. | Hogarth | $25

Lydia Millet is the writer, most not too long ago, of “A Kids’s Bible.” Her subsequent novel, “Dinosaurs,” will probably be printed in October.

Culture

New Crime Novels With Unexpected Twists

By Jeffery Deaver

Colter Shaw is a professional “rewards seeker,” a skilled tracker who specializes in finding missing people — usually for the reward money, though sometimes out of the goodness of his heart. It’s a simple enough vocation and yet, as the suspense veteran Deaver has demonstrated in four prior Shaw novels (and the TV adaptation “Tracker”), the ways in which Shaw finds peril — or peril finds him — keep multiplying. In SOUTH OF NOWHERE (Putnam, 403 pp., $30), his sister Dorion implores him to help to locate potential survivors after a levee collapses in a small Northern California town.

From here, Deaver is off to the proverbial races. Does every chapter have a twist? Pretty much. Is Colter just likable enough to brush off needless conflict and still find time for romance? Definitely. Is the writing a little too reminiscent of detailed outlines like the ones Deaver is known to fashion before writing a first draft? You bet. Could I put the book down? Not a chance.

The Colter Shaw series prioritizes action and the constant possibility of calamity, leaving only the barest amount of room for character development, like Colter’s continued grappling with the effects of his survivalist upbringing. The books don’t measure up to the best of Deaver’s Lincoln Rhyme novels, but they all accomplish their mission: thrilling engagement.

by Uzma Jalaluddin

Kausar Khan, introduced in DETECTIVE AUNTY (Harper Perennial, 326 pp., paperback, $17.99), has spent the past 20 years relishing the stability of placid North Bay, where she and her husband moved after fleeing busy, bustling Toronto in the wake of a family tragedy.

But then her husband dies shortly after being diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, and her daughter, Sana, calls with upsetting news: “I’m in trouble. There’s been a murder, and I’m the prime suspect.” It seems Sana’s landlord has been found inside her clothing store with a dagger in his chest. Kausar returns to Toronto’s Golden Crescent neighborhood as both a concerned mother and a tenacious amateur sleuth.

The case against Sana is strong, but as Kausar discovers, the murder victim had many enemies. If only the ghosts of Kausar’s past would stop haunting her present-day investigation!

Jalaluddin, who has crossed into crime fiction from the romantic comedy genre, doesn’t skimp on plotting — the whodunit twist caught me pleasingly flat-footed — but shines most with character and community, showing the complexities of mother-daughter relationships and the variability of longtime friendships. “Detective Aunty” is the first in a new series and I certainly welcome more installments.

by Michael McGarrity

Reading Michael McGarrity’s noir novel NIGHT IN THE CITY (Norton, 263 pp., $28.99), about the midcentury death of a Manhattan socialite named Laura Neilson, I found it difficult to avoid thinking about Vera Caspary’s 1943 classic suspense novel “Laura” (and the equally classic film adaptation featuring Gene Tierney and Dana Andrews). While I wished for more structural innovation along the lines of what Caspary accomplished, I did enjoy McGarrity’s more conventional narrative here: A man finds his ex-lover murdered and must clear his name, rooting out widespread corruption as the atmosphere thickens.

The man is the assistant district attorney Sam Monroe, who dated Laura for a time and never really got over the way she broke up with him by bringing a new flame to the local bar that was “their private haunt and rendezvous.” So when she summons him to her Manhattan penthouse, off Sam goes, waved in by an expectant doorman — only to find her body, his Army dog tags wrapped around her neck. One thing is clear: He’s been set up. With the help of an intrepid private eye and his former lover’s diary, Sam sets out to find her killer.

McGarrity paints a seedy portrait of a bygone New York that pulses with life, lust and larceny.

by Leonie Swann; translated by Amy Bojang

Finally, it gives me great pleasure that Swann’s exceedingly delightful Sheep Detective books are once again available for American audiences. “Three Bags Full,” first published in 2005 and reissued in February, introduced an intrepid flock on the case of who had killed their beloved shepherd. In BIG BAD WOOL (Soho Crime, 384 pp., $28.95), the sheep — including Zora, “a Blackface sheep with a weakness for the abyss,” Ramesses, a “nervous young ram full of good ideas,” and Miss Maple, “the cleverest sheep in the flock and maybe even the world” — return with a new minder, Rebecca.

They’re wintering next to a French château, which sounds idyllic, but the disappearance of other sheep, the mounting deaths of deer and, eventually, a human, strike fear in the hearts of the flock, who are worried they or their shepherd may be next. Is it a werewolf, the shape-shifting creature called Garou, as the local goats seem to believe? Or a more prosaic yet sinister culprit? How the sheep discover the truth will enchant readers who pay close attention.

Culture

Book Review: ‘Warhol’s Muses,’ by Laurence Leamer

Leamer is undeniably excellent at setting a scene, especially a louche one. He knows just when to have someone wonder if he’s caught crabs from a couch or a crotch. And Leamer is very good on rich people playing at being disheveled, tuned to the comic possibilities of that particular brand of tourism. (Holzer, of Florida real estate wealth, announces after seeing the Stones for the first time that “they’re all from the lower classes. … There is no class anymore. Everyone is equal.” Leamer adds that Holzer’s “maid and butler might have disagreed.”) Nearly every page has at least one great sleazy anecdote or pinch of gossip.

The problem is that so many of these scenes, however expertly set, are variations on the same stale theme of boomers getting up to wild stuff because the times they were a-changin’. Does anyone still need reminding that “the ’60s was a decade of radical political and cultural dissent”? Or that it was once considered shocking that a high-culture figure such as Rudolf Nureyev could go straight from a performance of “Swan Lake” to dancing “to rock ’n’ roll in a nightclub wearing dungarees. Dungarees! Not a suit and tie like some uptight New York businessman”? Reading this book felt akin to being trapped in an endless Time-Life loop of jingle jangle mornings, lazy Sunday afternoons and warm San Franciscan nights, the author providing the stentorian voice-over as the usual footage rolls by: Bob Dylan “would soon emerge as the poetic troubadour of the ’60s”; Brian Jones, “addicted to drugs and sex … was on a short road to an early death”; Jim Morrison, “a troubadour of the counterculture … wrote poetic lyrics that chronicled the lives of his generation.”

Such minor sins might have been forgiven had I ultimately gleaned some deep or unforeseen insight into the lives of the book’s subjects — a group that includes Ultra Violet, Ingrid Superstar, Brigid Berlin and other Factory figures — or, failing that, into Andy Warhol’s work. But I got neither. Nor was I convinced by the whopping claim that “without his Superstars, Warhol might never have become a world-celebrated artist.”

Meeting these 10 historical actors in roughly chronological order as they enter Warhol’s life, one has a view of the artist and his milieu that actually narrows rather than widens. Warhol, a shape-shifter so manic and intense that he could slide into several personas in the span of a single season, is here reduced to a necessarily static figure so that the women can bounce off him. Which is fine as a narrative strategy, but then not much happens to the women, either. As each one flickers into view, her upbringing (often troubled) is dutifully covered before she provides some service to Warhol — as entertainment, as emotional consort, as visual material, as key holder to Park Avenue penthouses — and then fades out to make room for the next one. (Sedgwick is the exception, a frequent and always beguiling presence; Solanas, the would-be assassin, and not one of the 10 Superstars, stands out as foil rather than helpmeet, but appears only briefly.)

Rarely is there any sense of genuine collaboration or exchange. The book’s subtitle gives away the game: In the end, these women of varied backgrounds, with their respective dreams and desires, are all here to play the same passive role — to be inevitably and unsurprisingly “destroyed by the Factory fame machine.”

Culture

Book Review: ‘The Family Dynamic,’ by Susan Dominus

Take the Murguia family: Amalia and Alfredo immigrated from a small region in central Mexico to Kansas City, and had seven children, five of whom shared three beds in one of the house’s two bedrooms. Alfred, one of the older children, excelled academically and was the first in his family to enroll in college — and, at every stage, helped guide his siblings into a variety of educational and social opportunities. As Dominus writes, “What the siblings had going for them above all else was one another.” They “pushed one another but also provided logistical support, connections and counsel,” along with “unquestionable loyalty.”

Similarly, the Chens, who immigrated from China after having violated that country’s one-child policy, settled in Virginia, where they opened a restaurant. While the parents had high standards, they had little time to guide their children. Instead, their cousin tells Dominus that “when he pictures one Chen child playing piano, a sibling is on the bench as well, refining the younger sibling’s technique; they leaned over homework together, the older teaching the younger.”

In large measure, the families Dominus portrays are not particularly well off. But what she calls “enterprising parents” go to great lengths to expose their children to music, theater, museums, libraries and, most important, mentors. One of the customers at the Chens’ restaurant was the head of a high school marching band; he volunteered to give their child lessons — and that child became a drum major.

Laurence Paulus, a producer of arts television programming and of modest means, took his children to openings at the Metropolitan Opera. Unable to afford tickets, they sat outside the theater to absorb the charged atmosphere, a transistor radio broadcasting the music. They waited in line for free performances of Shakespeare in the Park; they played music at home. One daughter became a world-famous theater director; another, the principal harpist in one of Mexico’s premier orchestras; their brother would co-found NY1, one of the nation’s first 24-hour community TV stations.

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoSpotify already has an app ready to test Apple’s new rules

-

Cleveland, OH1 week ago

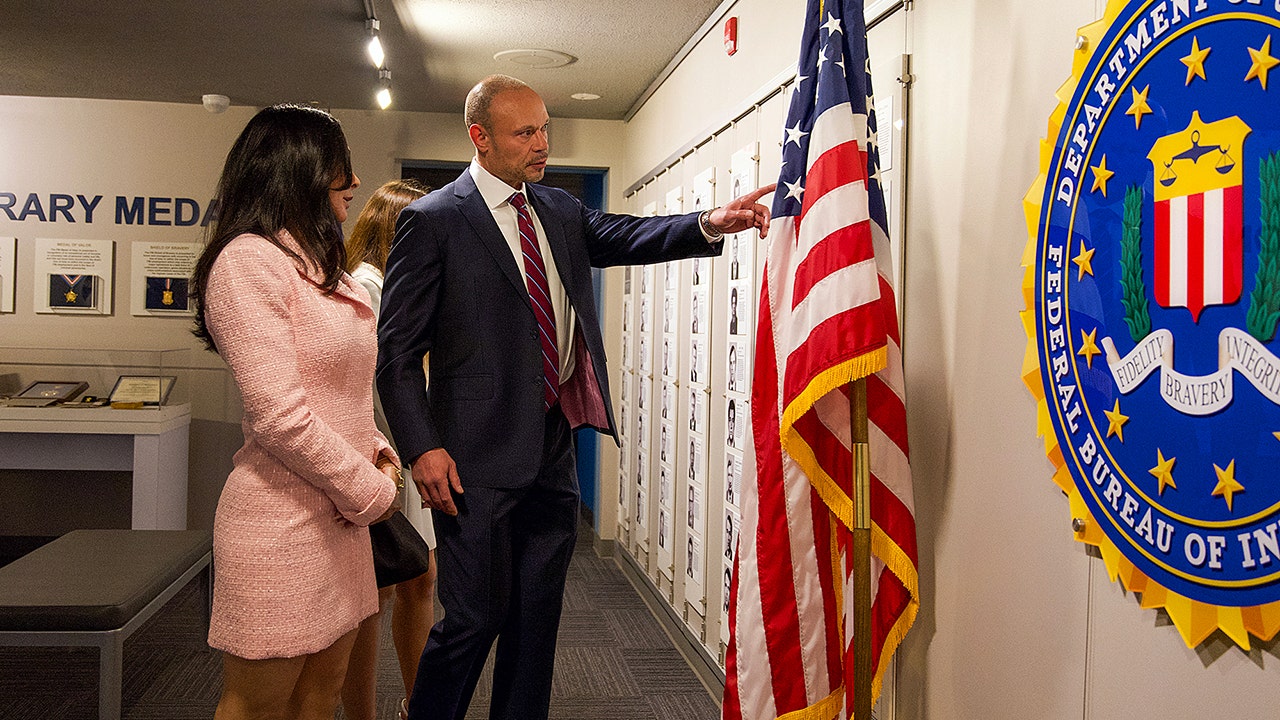

Cleveland, OH1 week agoWho is Gregory Moore? Former divorce attorney charged for murder of Aliza Sherman in downtown Cleveland

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoU.S. and China Dig In on Trade War, With No Plans for Formal Talks

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoFamily of 8-Year-Old Migrant Girl Who Died in U.S. Custody Seeks $15 Million

-

Politics1 week ago

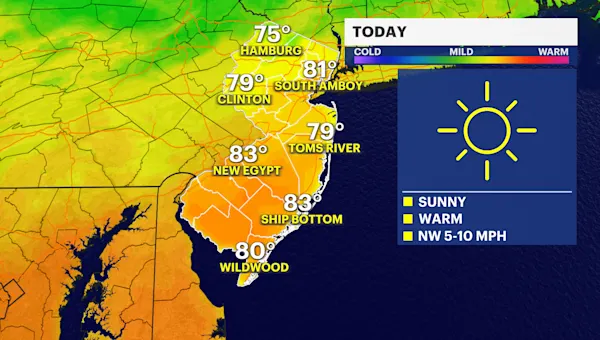

Politics1 week agoRep. Mikie Sherrill suggests third Trump impeachment as she campaigns to be next New Jersey governor

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump posts AI image of himself as Pope amid Vatican's search for new pontiff

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoWhy are relations between Algeria and France so bad?

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoAre Politicians Too Old? California Democrats Want to Debate an Age Cap.