Alaska

Alaskan Woman Drops Thanksgiving Turkeys from Plane to Help Feed Off-Grid Neighbors

When she heard that some of her neighbors were eating squirrels for Thanksgiving, a local pilot thought she’d lend a helping wing.

Many people believe turkeys can’t fly. They can, actually, in more ways than one.

Esther Sanderlin lives in rural Skwentna and West Susitna Valley Alaska, where flying small single-engine or prop planes is a common mode of personal transportation.

“I was visiting our newest neighbor and they were talking about splitting a squirrel three ways for dinner, and how that didn’t really go very far,” Sanderlin told Alaska’s NBC affiliate KTUU on the Monday in advance of Turkey Day.

“And I just had a thought at that moment, ‘You know what, I’m going to airdrop them a turkey for Thanksgiving,’ because I recently rebuilt my first airplane with my dad and so I can do that really easily.”

Sanderlin grew up occasionally receiving turkeys at her home via air-drop after the roads froze over in late autumn. She combined these wild childhood memories with the news of the squirrel dinner and decided she ought to pay it forward.

This year she’s dropping 30 to 40 turkeys to ensure her neighbors have as much to eat as they like on the day to be thankful for friends and family.

ALSO CHECK OUT: Virginians Deliver 114,000 Pounds of Winter Warmth to Refugees in Turkey

She doesn’t need to attach a parachute to them, as the soft snow below, and the frozen flesh of the turkey, means that a hard landing is no harm no fowl.

Speaking to the NBC, she said she hopes to turn her turkey drops into a nonprofit in the future so that she can extend her reach to more communities across Alaska.

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE: Police Give Motorists a Thanksgiving Surprise–Handing Out Free Turkeys Instead of Tickets

For the moment, she has a Facebook page called the Alaska Turkey Bomb.

“Huge shout out to everyone that helped with this year’s Turkey bombing! It was a success and thanks to many, we were able to deliver 36 Turkeys to the Yentna and Skwentna River area!” a post on the page read.

SHARE This Amazing Display Of Neighborliness In America’s Frigid North…

Alaska

Alaska delegation mixed on Venezuela capture legality, day before presidential war powers vote

ANCHORAGE, Alaska (KTUU) – Alaska’s congressional delegation had mixed reactions Wednesday on the legality of the Trump administration’s actions in Venezuela over the weekend, just a day before they’re set to vote on a bill ending “hostilities” in Venezuela.

It comes days after former Venezuelan Nicolás Maduro was captured by American forces and brought to the United States in handcuffs to face federal drug trafficking charges.

All U.S. Senators were to be briefed by the administration members at 10 a.m. ET Wednesday, including Secretary of State Marco Rubio and Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth, according to CBS News.

Spokespersons for Alaska Sens. Lisa Murkowski, R-Alaska, and Dan Sullivan, R-Alaska, say they were at that meeting, but from their responses, the two shared different takeaways.

Sullivan, who previously commended the Trump administration for the operation in Venezuela, told KDLL after his briefing that the next steps in Venezuela would be done in three phases.

“One is just stabilization. They don’t want chaos,” he said.

“The second is to have an economic recovery phase … and then finally, the third phase is a transition to conduct free and fair elections and perhaps install the real winner of the 2024 election there, which was not Maduro.”

Murkowski spokesperson Joe Plesha said she had similar takeaways to Sullivan on the ousting of Maduro, but still held concerns on the legality.

“Nicolás Maduro is a dictator who led a brutally oppressive regime, and Venezuela and the world are better places without him in power,” Plesha said in a statement Wednesday. “While [Murkowski] continues to question the legal and policy framework that led to the military operation, the bigger question now is what happens next.”

Thursday, the Senate will decide what happens next when they vote on a war powers resolution which would require congressional approval to “be engaged in hostilities within or against Venezuela,” and directs the president to terminate the use of armed forces against Venezuela, “unless explicitly authorized by a declaration of war or specific authorization for use of military force.”

Several House leaders have also received a briefing from the administration according to CBS News. A spokesperson for Rep. Nick Begich, R-Alaska, said he received a House briefing and left believing the actions taken by the administration were legal.

“The information provided in today’s classified House briefing further confirmed that the actions taken by the Administration to obtain Maduro were necessary, time-dependent, and justified; and I applaud our military and the intelligence community for their exceptional work in executing this operation,” Begich said in a statement.

Looming vote

Sen. Tim Kaine, D-VA, authored the war powers resolution scheduled for debate Thursday at 11 a.m. ET — 7 a.m. AKST.

It’s a resolution which was one of the biggest topics of discussion on the chamber floors Wednesday.

Sen. Rand Paul, R-KY, said on the Senate floor Wednesdya that the actions taken by the administration were an “act of war,” and the president’s capture of Maduro violated the checks and balances established in the constitution, ending his remarks by encouraging his colleagues to vote in favor of the resolution.

“The constitution is clear,” Paul said. “Only Congress can declare a war.”

If all Democrats and independents vote for the Kaine resolution, and Paul keeps to his support, the bill will need three more votes to pass. If there is a tie, the vice president is the deciding vote.

“It’s as if a magical dust of soma has descended through the ventilation systems of congressional office buildings,” Paul continued Wednesday, referring to a particular type of muscle relaxant.

“Vague faces in permanent smiles and obedient applause indicate the degree that the majority party has lost its grip and have become eunuchs in the thrall of presidential domination.”

Legality of actions under scrutiny

U.S. forces arrested Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores, from their Caracas home in an overnight operation early Saturday morning, Alaska time. Strikes accompanying the capture killed about 75 people, including military personnel and civilians, according to U.S. government officials granted anonymity by The Washington Post.

Maduro pleaded not guilty Monday in a New York courtroom to drug trafficking charges that include leading the “Cartel of the Suns,” a narco-trafficking organization comprised of high-ranking Venezuelan officials. The U.S. offered a $50 million reward for information leading to his capture.

Whether the U.S. was legally able to capture Maduro under both domestic and international law has been scrutinized in the halls of Congress. Members of the administration, like Secretary of State Marco Rubio, have been open in defending what they say was a law enforcement operation carrying out an arrest warrant, The Hill reports. Lawmakers, like Paul or Sen. Chuck Schumer, D-NY, say the actions were an act of war and a violation of the constitution.

While the president controls the military as commander in chief, Congress constitutionally has the power to declare wars. Congressional Democrats have accused Trump of skirting the Constitution by not seeking congressional authorization before the operation.

Murkowski has not outright condemned or supported the actions taken by the administration, saying in a statement she was hopeful the world was safer without Maduro in power, but the way the operation was handled is “important.”

Sullivan, on the other hand, commended Trump and those involved in the operation for forcing Maduro to “face American justice,” in an online statement.

Begich spokesperson Silver Prout told Alaska’s News Source Monday the Congressman believed the operation was “a lawful execution of a valid U.S. arrest warrant on longstanding criminal charges against Nicolás Maduro.”

The legality of U.S. military actions against Venezuela has taken significant focus in Washington over the past several months, highlighted by a “double-tap” strike — a second attack on the same target after an initial strike — which the Washington Post reported killed people clinging to the wreckage of a vessel after the military already struck it. The White House has confirmed the follow-up attack.

Sullivan, who saw classified video of the strike, previously told Alaska’s News Source in December he believed actions taken by the U.S. did not violate international law.

“I support them doing it, but they have to get it right,” he said. “I think so far they’re getting it right.”

Murkowski, who has not seen the video, previously said at an Anchorage press event the takeaways on that strike’s legality seem to be divided along party lines.

“I spoke to a colleague who is on the Intelligence Committee, a Republican, and I spoke to a colleague, a Democrat, who is on the Senate Armed Services Committee … their recollection or their retelling of what they saw [was] vastly different.”

See a spelling or grammar error? Report it to web@ktuu.com

Copyright 2026 KTUU. All rights reserved.

Alaska

National Native helpline for domestic violence and sexual assault to open Alaska-specific service

Alaska

Dozens of vehicle accidents reported, Anchorage after-school activities canceled, as snowfall buries Southcentral Alaska

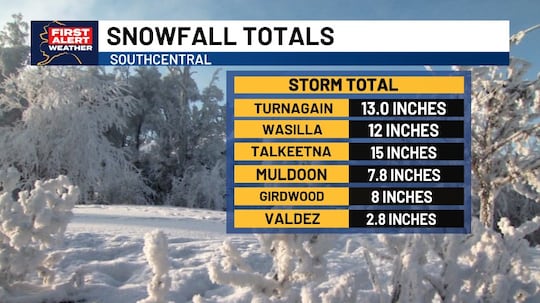

ANCHORAGE, Alaska (KTUU) – Up to a foot of snow has fallen in areas across Southcentral as of Tuesday, with more expected into Wednesday morning.

All sports and after-school activities — except high school basketball and hockey activities — were canceled Tuesday for the Anchorage School District. The decision was made to allow crews to clear school parking lots and manage traffic for snow removal, district officials said.

“These efforts are critical to ensuring schools can safely remain open [Wednesday],” ASD said in a statement.

The Anchorage Police Department’s accident count for the past two days shows there have been 55 car accidents since Monday, as of 9:45 a.m. Tuesday. In addition, there have been 86 vehicles in distress reported by the department.

The snowfall — which has brought up to 13 inches along areas of Turnagain Arm and 12 inches in Wasilla — is expected to continue Tuesday, according to latest forecast models. Numerous winter weather alerts are in effect, and inland areas of Southcentral could see winds up to 25 mph, with coastal areas potentially seeing winds over 45 mph.

Some areas of Southcentral could see more than 20 inches of snowfall by Wednesday, with the Anchorage and Eagle River Hillsides, as well as the foothills of the Talkeetna Mountain, among the areas seeing the most snowfall.

See a spelling or grammar error? Report it to web@ktuu.com

Copyright 2026 KTUU. All rights reserved.

-

Detroit, MI5 days ago

Detroit, MI5 days ago2 hospitalized after shooting on Lodge Freeway in Detroit

-

Dallas, TX3 days ago

Dallas, TX3 days agoDefensive coordinator candidates who could improve Cowboys’ brutal secondary in 2026

-

Technology2 days ago

Technology2 days agoPower bank feature creep is out of control

-

Health4 days ago

Health4 days agoViral New Year reset routine is helping people adopt healthier habits

-

Nebraska1 day ago

Nebraska1 day agoOregon State LB transfer Dexter Foster commits to Nebraska

-

Politics4 days ago

Politics4 days agoDan Bongino officially leaves FBI deputy director role after less than a year, returns to ‘civilian life’

-

Nebraska2 days ago

Nebraska2 days agoNebraska-based pizza chain Godfather’s Pizza is set to open a new location in Queen Creek

-

Louisiana3 days ago

Louisiana3 days agoInternet company started with an antenna in a tree. Now it’s leading Louisiana’s broadband push.