Science

She’s Trying to Stay Ahead of Alzheimer’s, in a Race to the Death

Soon, Irene Mekel will need to pick the day she dies.

She’s not in any hurry: She quite likes her life, in a trim, airy house in Castricum, a Dutch village by the sea. She has flowers growing in her back garden, and there is a street market nearby where vendors greet villagers by name. But if her life is going to end the way she wants, she will have to pick a date, sooner than she might like.

“It’s a tragedy,” she said.

Ms. Mekel, 82, has Alzheimer’s disease. It was diagnosed a year ago. She knows her cognitive function is slowly declining, and she knows what is coming. She spent years working as a nurse, and she cared for her sister, who had vascular dementia. For now, she is managing, with help from her three children and a big screen in the corner of the living room that they update remotely to remind her of the date and any appointments.

In the not-so-distant future, it will no longer be safe for her to stay at home alone. She had a bad fall and broke her elbow in August. She does not feel she can live with her children, who are busy with careers and children of their own. She is determined that she will never move to a nursing home, which she considers an intolerable loss of dignity. As a Dutch citizen, she is entitled by law to request that a doctor help her end her life when she reaches a point of unbearable suffering. And so she has applied for a medically assisted death.

In 2023, shortly before her diagnosis, Ms. Mekel joined a workshop organized by the Dutch Association for Voluntary End of Life. There, she learned how to draft an advance request document that would lay out her wishes, including the conditions under which she would request what is called euthanasia in the Netherlands. She decided it would be when she could not recognize her children and grandchildren, hold a conversation or live in her own home.

But when Ms. Mekel’s family doctor read the advance directive, she said that while she supported euthanasia, she could not provide it. She will not do it for someone who has by definition lost the capacity to consent.

A rapidly growing number of countries around the world, from Ecuador to Germany, are legalizing medical assistance in dying. But in most of those countries, the procedure is available only to people with terminal illness.

The Netherlands is one of just four countries (plus the Canadian province of Quebec) that permit medically assisted death by advance request for people with dementia. But the idea is gaining support in other countries, as populations age and medical interventions mean more people live long enough to experience cognitive decline.

The Dutch public strongly supports the right to an assisted death for people with dementia. Yet most Dutch doctors refuse to provide it. They find that the moral burden of ending the life of someone who no longer has the cognitive capacity to confirm their wishes is too weighty to bear.

Ms. Mekel’s doctor referred her to the Euthanasia Expertise Center, in The Hague, an organization that trains doctors and nurses to provide euthanasia within the parameters of Dutch law and connects patients with a medical team that will investigate a request and provide assisted death to eligible patients in cases where their own doctors won’t. But even these doctors are reluctant to act after a person has lost mental capacity.

Last year, a doctor and a nurse from the center came every three months to meet with Ms. Mekel over tea. Ostensibly, they came to discuss her wishes for the end of her life. But Ms. Mekel knew they were really monitoring how quickly her mental faculties had declined. It might seem like a tea party, she said, “but I see them watching me.”

Dr. Bert Keizer is alert for a very particular moment: It is known as “five to 12” — five minutes to midnight. Doctors, patients and their caregivers engage in a delicate negotiation to time death for the last moment before a person loses that capacity to clearly state a rational wish to die. He will fulfill Ms. Mekel’s request to end her life only while she still is fully aware of what she is asking.

They must act before dementia has tricked her, as it has so many of his other patients, into thinking her mind is just fine.

“This balance is something so hard to discover,” he said, “because you as a doctor and she as your patient, neither of you quite knows what the prognosis is, how things will develop — and so the harrowing aspect of this whole thing is looking for the right time for the horrible thing.”

Ms. Mekel finds this negotiation deeply frustrating: The process does not allow for the idea that simply having to accept care can be considered a form of suffering, that worrying about what lies ahead is suffering, that loss of dignity is suffering. Whose assessment should carry more weight, she asks: current Irene Mekel, who sees loss of autonomy as unbearable, or future Irene, with advanced dementia, who is no longer unhappy, or can no longer convey that she’s unhappy, if someone must feed and dress her.

More than 500,000 of the 18 million people in the Netherlands have advance request documents like hers on file with their family doctors, explicitly laying out their wishes for physician-assisted death should they decline cognitively to a point they identify as intolerable. Most assume that an advance request will allow them to progress into dementia and have their spouses, children or caregivers choose the moment when their lives should end.

Yet of the 9,000 physician-assisted deaths in the Netherlands each year, just six or seven are for people who have lost mental capacity. The overwhelming majority are for people with terminal illnesses, mostly cancer, with a smaller number for people who have other nonterminal conditions that cause acute suffering — such as neurodegenerative disease or intractable depression.

Physicians, who were the primary drivers of the creation of the Dutch assisted dying law — not Parliament, or a constitutional court case, as in most other countries where the procedure is legal — have strong views about what they will and will not do. “Five to 12” is the pragmatic compromise that has emerged in the 23 years since the criminal code was amended to permit physicians to end lives in situations of “unbearable and irremediable suffering.”

A Shock

Ms. Mekel, petite and brisk, had suspected for some time before she received a diagnosis that she had Alzheimer’s. There were small, disquieting signs, and then one big one, when she took a taxi home one day and could not recognize a single house on the street where she had lived for 45 years, could not identify her own front door.

At that point, she knew it was time to start making plans.

She and her best friend, Jean, talked often about how they dreaded the idea of a nursing home, of needing someone to dress them, get them out of bed in the morning, of having their worlds shrink to a sunroom at the end of a ward.

“When you lose your own will, and you are no longer independent — for me, that’s my nightmare,” she said. “I would kill myself, I think.”

She knows how cognition can slip away almost imperceptibly, like mist over a garden on a spring morning. But the news that she would need to ask Dr. Keizer to end her life before such losses happened came as a shock.

Her distress at the accelerated timeline is not an uncommon response.

Dr. Pieter Stigter, a geriatric specialist who works in nursing homes and also as a consultant for the Expertise Center, must frequently explain to startled patients that their carefully drawn-up advance directives are basically meaningless.

“The first thing I tell them is, ‘I’m sorry, that’s not going to happen,’” he said. “Assisted dying while mentally incompetent, it’s not going to happen. So now we’re going to talk about how we’re going to avoid getting there.”

Patients who have cared for their own parents with dementia may specify in their advance directive that they do not wish to reach the point of being bedridden, incontinent or unable to feed themselves. “But still then, if someone is accepting it, patiently smiling, it’s going to be very hard to be convinced in that moment that even though someone described it in an earlier stage, that in that moment it is unbearable suffering,” Dr. Stigter said.

The first line people write in a directive is always, “‘If I get to the point I do not recognize my children,’” he said. “But what is recognition? Is it knowing someone’s name, or is it having a big smile when someone enters your room?”

Five-to-12 makes the burden being placed on physicians morally tolerable.

“As a doctor, you are the one who has to do it,” said Dr. Stigter, a warm and wiry 44-year-old. “I’m the one doing it. It has to feel good for me.”

Conversations about advance requests for assisted death in the Netherlands are shadowed by what many people who work in this field refer to, with a wince, as “the coffee case.”

In 2016, a doctor who provided an assisted death to a 74-year-old woman with dementia was charged with violating the euthanasia law. The woman had written an advance directive four years earlier, saying she wished to die before she needed to enter a care home. On the day her family chose, her doctor gave her a sedative in coffee, and then injected a stronger dose. But during the administration of the medication that would stop her heart, the woman awoke and resisted. Her husband and children had to hold her down so the doctor could complete the procedure.

The doctor was acquitted in 2019. The judge said the patient’s advance request was sufficient basis for the doctor to act. But the public recoil at the idea of the woman’s family holding her down while she died redoubled the determination of Dutch doctors to avoid such a situation.

A Day Too Late

Dr. Stigter never takes on a case assuming he will provide an assisted death. Cognitive decline is a fluid thing, he said, and so is a person’s sense of what is tolerable.

“The goal is an outcome that reflects what the patient wants — that can evolve all the time,” he said. “Someone can say, ‘I want euthanasia in the future’, but actually when the moment is there, it’s different.”

Dr. Stigter found himself explaining this to Henk Zuidema a few years ago. Mr. Zuidema, a tile setter, had early-onset Alzheimer’s at 57. He was told he would no longer be permitted to drive, and so he would have to stop working and give up his main hobby, driving a vintage motocross bike with friends.

A gruff, stoic family man, Mr. Zuidema was appalled at the idea of no longer providing for his wife or caring for his family, and he told them he would seek a medically assisted death before the disease left him totally dependent.

His own family doctor was not willing to help him die, nor was anyone in her practice, and so his daughter Froukje Zuidema found the Expertise Center. Dr. Stigter was assigned to his case and began driving 30 minutes from his office in the city of Groningen every month to visit Mr. Zuidema at his home in the farming village of Boelenslaan.

“Pieter was very clear: ‘You have to tell me when,’” Ms. Zuidema said. “And that was very hard, because Dad had to make the decision.”

When he grasped that the disease might impair his judgment, and thus cause him to overestimate his mental competence, Mr. Zuidema quickly settled on a plan to die within months. His family was shocked, but for him the trade-off was clear: “Better a year too early than a day too late,” he would say.

Dr. Stigter pushed Mr. Zuidema to define what, exactly, his suffering would be. “He would say, ‘Why is it so bad to get old like that?’” Ms. Zuidema recalled. “‘Why is it so bad to go to a nursing home?’” She said the doctor would tell her father, “ ‘Your idea of suffering is not the same as mine, so help me understand why this is suffering, for you.’ “

Her reticent father struggled to explain, and finally put it in a letter: “I don’t want to lose my role as a husband and a father, I do not want to be unable to help people any longer … Suffering would be if I could no longer be alone with my grandchildren because people did not trust me any longer: even this thought makes me crazy … Do not be misled by a moment in which I look happy but instead look back at this moment when I am with my wife and children.’”

The progress of dementia is unpredictable, and Mr. Zuidema did not experience a rapid decline. In the end, Dr. Stigter visited each month for a year and a half, and the two men developed a relationship of trust, Ms. Zuidema said.

Dr. Stigter provided a medically assisted death in September 2022. Mr. Zuidema, then 59, was in a camp bed near the living room window, his wife and children at his side. His daughter said she sees Dr. Stigter “as a real hero.” She has no doubt her father would have died by suicide even sooner, had he not been confident he could receive an assisted death from his doctor.

Still, she is wistful about the time they didn’t have. If the advance directive had worked as defined in the law — if there had been no fear of missing the moment — her father might have had more months, more time sitting on the vast green lawn between their houses and watching his grandchildren kick a soccer ball, more time with his dog at his feet, more time sitting on a riverbank with his grandson and a lazy fishing line in the water.

“He would have stayed longer,” Ms. Zuidema said.

Her sense that her father’s death was rushed does not outweigh her gratitude that he had the death he wanted. And her feeling is widely shared among families, according to research by Dr. Agnes van der Heide, a professor of end-of-life care and decision making at Erasmus Medical College, University Medical Center Rotterdam.

“The large majority of the Dutch population feel safe in the hands of the doctor, with regards to euthanasia, and they very much appreciate that the doctor has a significant role there and independently judges whether or not they think that ending of life is justifiable,” she said.

For five to 12 to work, doctors should know their patients well and have time to track changes in their cognition. As the public health system in the Netherlands is increasingly strained, and short of family practitioners, that model of care is becoming less common.

Ms. Mekel’s physician, Dr. Keizer, said his lengthy visits to patients were possible only because he is mostly retired and not in a hurry. (In addition to his half-time practice, he writes regular op-eds for Dutch newspapers and comments on high-profile cases. He is a bit of an assisted-dying celebrity, and, Ms. Mekel confided, the other older women at the right-to-die workshops were envious when they learned that he had been assigned as her physician.)

Now that he is clear on her wishes, the tea parties are paused; he will resume the visits when her children tell him there has been a significant change in her awareness or ability to function — when they feel that five to 12 is close.

An Intolerable Price

Ms. Mekel is haunted by what happened to her best friend, Jean, who, she said, “missed the moment” for an assisted death.

Although Jean was determined to avoid moving to a nursing home, she lived in one for eight years. Ms. Mekel visited her there until Jean became unable to carry on a conversation. Ms. Mekel continued to call her and sent emails that Jean’s children read to her. Jean died in the nursing home in July, at 87.

Jean is the reason Ms. Mekel is willing to plan her death for sooner than she might like.

Yet Jean’s son, Jos Van Ommeren, is not sure that Ms. Mekel understands her friend’s fate correctly. He agrees that his mother dreaded the nursing home, but once she got there, she had some good years, he said. She was a voracious reader and devoured a book from the residence library each day. She had loved sunbathing all her life, and the staff made sure she could sit in the sun and read for hours.

Most of the last years were good years, Mr. Van Ommeren said, and to have those, it was worth the price of giving up the assisted death she had requested.

For Ms. Mekel, that price is intolerable.

Her youngest son, Melchior, asked her gently, not long ago, if a nursing home might be OK, if by the time she got there she wasn’t so aware of her lost independence.

Ms. Mekel shot him a look of affectionate disgust.

“No,” she said. “No. It wouldn’t.”

Veerle Schyns contributed reporting from Amsterdam.

Audio produced by Tally Abecassis.

Science

California confirms first measles case for 2026 in San Mateo County as vaccination debates continue

Barely more than a week into the new year, the California Department of Public Health confirmed its first measles case of 2026.

The diagnosis came from San Mateo County, where an unvaccinated adult likely contracted the virus from recent international travel, according to Preston Merchant, a San Mateo County Health spokesperson.

Measles is one of the most infectious viruses in the world, and can remain in the air for two hours after an infected person leaves, according to the CDPH. Although the U.S. announced it had eliminated measles in 2000, meaning there had been no reported infections of the disease in 12 months, measles have since returned.

Last year, the U.S. reported about 2,000 cases, the highest reported count since 1992, according to CDC data.

“Right now, our best strategy to avoid spread is contact tracing, so reaching out to everybody that came in contact with this person,” Merchant said. “So far, they have no reported symptoms. We’re assuming that this is the first [California] measles case of the year.”

San Mateo County also reported an unvaccinated child’s death from influenza this week.

Across the country, measles outbreaks are spreading. Today, the South Carolina State Department of Public Health confirmed the state’s outbreak had reached 310 cases. The number has been steadily rising since an initial infection in July spread across the state and is now reported to be connected with infections in North Carolina and Washington.

Similarly to San Mateo’s case, the first reported infection in South Carolina came from an unvaccinated person who was exposed to measles while traveling internationally.

At the border of Utah and Arizona, a separate measles outbreak has reached 390 cases, stemming from schools and pediatric centers, according to the Utah Department of Health and Human Services.

Canada, another long-standing “measles-free” nation, lost ground in its battle with measles in November. The Public Health Agency of Canada announced that the nation is battling a “large, multi-jurisdictional” measles outbreak that began in October 2024.

If American measles cases follow last year’s pattern, the United States is facing losing its measles elimination status next.

For a country to lose measles-free status, reported outbreaks must be of the same locally spread strain, as was the case in Canada. As many cases in the United States were initially connected to international travel, the U.S. has been able to hold on to the status. However, as outbreaks with American-origin cases continue, this pattern could lead the Pan American Health Organization to change the country’s status.

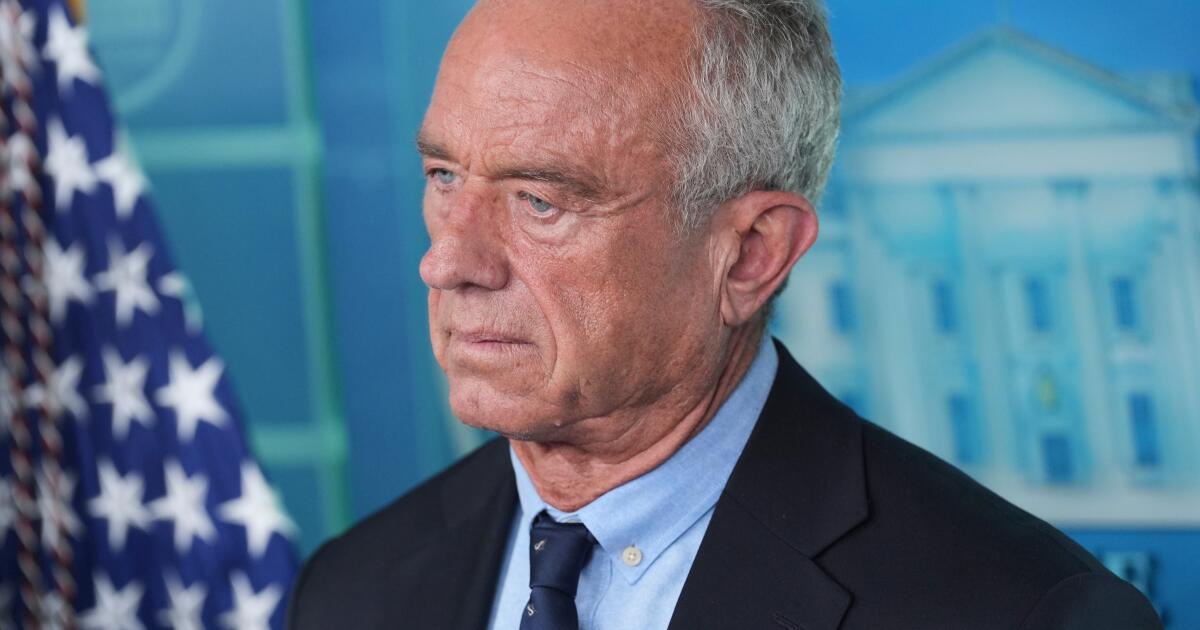

In the first year of the Trump administration, officials led by Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. have promoted lowering vaccine mandates and reducing funding for health research.

In December, Trump’s presidential memorandum led to this week’s reduced recommended childhood vaccines; in June, Kennedy fired an entire CDC vaccine advisory committee, replacing members with multiple vaccine skeptics.

Experts are concerned that recent debates over vaccine mandates in the White House will shake the public’s confidence in the effectiveness of vaccines.

“Viruses and bacteria that were under control are being set free on our most vulnerable,” Dr. James Alwine, a virologist and member of the nonprofit advocacy group Defend Public Health, said to The Times.

According to the CDPH, the measles vaccine provides 97% protection against measles in two doses.

Common symptoms of measles include cough, runny nose, pink eye and rash. The virus is spread through breathing, coughing or talking, according to the CDPH.

Measles often leads to hospitalization and, for some, can be fatal.

Science

Trump administration declares ‘war on sugar’ in overhaul of food guidelines

The Trump administration announced a major overhaul of American nutrition guidelines Wednesday, replacing the old, carbohydrate-heavy food pyramid with one that prioritizes protein, healthy fats and whole grains.

“Our government declares war on added sugar,” Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. said in a White House press conference announcing the changes. “We are ending the war on saturated fats.”

“If a foreign adversary sought to destroy the health of our children, to cripple our economy, to weaken our national security, there would be no better strategy than to addict us to ultra-processed foods,” Kennedy said.

Improving U.S. eating habits and the availability of nutritious foods is an issue with broad bipartisan support, and has been a long-standing goal of Kennedy’s Make America Healthy Again movement.

During the press conference, he acknowledged both the American Medical Association and the American Assn. of Pediatrics for partnering on the new guidelines — two organizations that earlier this week condemned the administration’s decision to slash the number of diseases that U.S. children are vaccinated against.

“The American Medical Association applauds the administration’s new Dietary Guidelines for spotlighting the highly processed foods, sugar-sweetened beverages, and excess sodium that fuel heart disease, diabetes, obesity, and other chronic illnesses,” AMA president Bobby Mukkamala said in a statement.

Science

Contributor: With high deductibles, even the insured are functionally uninsured

I recently saw a patient complaining of shortness of breath and a persistent cough. Worried he was developing pneumonia, I ordered a chest X-ray — a standard diagnostic tool. He refused. He hadn’t met his $3,000 deductible yet, and so his insurance would have required him to pay much or all of the cost for that scan. He assured me he would call if he got worse.

For him, the X-ray wasn’t a medical necessity, but it would have been a financial shock he couldn’t absorb. He chose to gamble on a cough, and five days later, he lost — ending up in the ICU with bilateral pneumonia. He survived, but the cost of his “savings” was a nearly fatal hospital stay and a bill that will quite likely bankrupt him. He is lucky he won’t be one of the 55,000 Americans to die from pneumonia each year.

As a physician associate in primary care, I serve as a frontline witness to this failure of the American approach to insurance. Medical professionals are taught that the barrier to health is biology: bacteria, viruses, genetics. But increasingly, the barrier is a policy framework that pressures insured Americans to gamble with their lives. High-deductible health plans seem affordable because their monthly premiums are lower than other plans’, but they create perverse incentives by discouraging patients from seeking and accepting diagnostics and treatments — sometimes turning minor, treatable issues into expensive, life-threatening emergencies. My patient’s gamble with his lungs is a microcosm of the much larger gamble we are taking with the American public.

The economic theory underpinning these high deductibles is known as “skin in the game.” The idea is that if patients are responsible for the first few thousand dollars of their care, they will become savvy consumers, shopping around for the best value and driving down healthcare costs.

But this logic collapses in the exam room. Healthcare is not a consumer good like a television or a used car. My patient was not in a position to “shop around” for a cheaper X-ray, nor was he qualified to determine if his cough was benign or deadly. The “skin in the game” theory assumes a level of medical literacy and market transparency that simply doesn’t exist in a moment of crisis. You can compare the specs of two SUVs; you cannot “shop around” for a life-saving diagnostic while gasping for air.

A 2025 poll from the Kaiser Family Foundation points to this reality, finding that up to 38% of insured American adults say they skipped or postponed necessary healthcare or medications in the past 12 months because of cost. In the same poll, 42% of those who skipped care admitted their health problem worsened as a result.

This self-inflicted public health crisis is set to deteriorate further. The Congressional Budget Office estimates roughly 15 million people will lose health coverage and become uninsured by 2034 because of Medicaid and Affordable Care Act marketplace cuts. That is without mentioning the millions more who will see their monthly premiums more than double if premium tax credits are allowed to expire. If that happens, not only will millions become uninsured but also millions more will downgrade to “bronze” plans with huge deductibles just to keep their premiums affordable. We are about to flood the system with “insured but functionally uninsured” patients.

I see the human cost of this “functional uninsurance” every week. These are patients who technically have coverage but are terrified to use it because their deductibles are so large they may exceed the individuals’ available cash or credit — or even their net worth. This creates a dangerous paradox: Americans are paying hundreds of dollars a month for a card in their wallet they cannot afford to use. They skip the annual physical, ignore the suspicious mole and ration their insulin — all while technically insured. By the time they arrive at my clinic, their disease has often progressed to a catastrophic event, from what could have been a cheap fix.

Federal spending on healthcare should not be considered charity; it is an investment in our collective future. We cannot expect our children to reach their full potential or our workforce to remain productive if basic healthcare needs are treated as a luxury. Inaction by Congress and the current administration to solve this crisis is legislative malpractice.

In medicine, we are trained to treat the underlying disease, not just the symptoms. The skipped visits and ignored prescriptions are merely symptoms; the disease is a policy framework that views healthcare as a commodity rather than a fundamental necessity. If we allow these cuts to proceed, we are ensuring that the American workforce becomes sicker, our hospitals more overwhelmed and our economy less resilient. We are walking willingly into a public health crisis that is entirely preventable.

Joseph Pollino is a primary care physician associate in Nevada.

Insights

L.A. Times Insights delivers AI-generated analysis on Voices content to offer all points of view. Insights does not appear on any news articles.

Viewpoint

Perspectives

The following AI-generated content is powered by Perplexity. The Los Angeles Times editorial staff does not create or edit the content.

Ideas expressed in the piece

-

High-deductible health plans create a barrier to necessary medical care, with patients avoiding diagnostics and treatments due to out-of-pocket cost concerns[1]. Research shows that 38% of insured American adults skipped or postponed necessary healthcare or medications in the past 12 months because of cost, with 42% reporting their health worsened as a result[1].

-

The economic theory of “skin in the game”—which assumes patients will shop around for better healthcare values if they have financial responsibility—fails in medical practice because patients lack the medical literacy to make informed decisions in moments of crisis and cannot realistically compare pricing for emergency or diagnostic services[1].

-

Rising deductibles are pushing enrollees toward bronze plans with deductibles averaging $7,476 in 2026, up from the average silver plan deductible of $5,304[1][4]. In California’s Covered California program, bronze plan enrollment has surged to more than one-third of new enrollees in 2026, compared to typically one in five[1].

-

Expiring federal premium tax credits will more than double out-of-pocket premiums for ACA marketplace enrollees in 2026, creating an expected 75% increase in average out-of-pocket premium payments[5]. This will force millions to either drop coverage or downgrade to bronze plans with massive deductibles, creating a population of “insured but functionally uninsured” people[1].

-

High-deductible plans pose particular dangers for patients with chronic conditions, with studies showing adults with diabetes involuntarily switched to high-deductible plans face 11% higher risk of hospitalization for heart attacks, 15% higher risk for strokes, and more than double the likelihood of blindness or end-stage kidney disease[4].

Different views on the topic

-

Expanding access to health savings accounts paired with bronze and catastrophic plans offers tax advantages that allow higher-income individuals to set aside tax-deductible contributions for qualified medical expenses, potentially offsetting higher out-of-pocket costs through strategic planning[3].

-

Employers and insurers emphasize that offering multiple plan options with varying deductibles and premiums enables employees to select plans matching their individual needs and healthcare usage patterns, allowing those who rarely use healthcare to save money through lower premiums[2]. Large employers increasingly offer three or more medical plan choices, with the expectation that employees choosing the right plan can unlock savings[2].

-

The expansion of catastrophic plans with streamlined enrollment processes and automatic display on HealthCare.gov is intended to make affordable coverage more accessible for certain income groups, particularly those above 400% of federal poverty level who lose subsidies[3].

-

Rising healthcare costs, including specialty drugs and new high-cost cell and gene therapies, are significant drivers requiring premium increases regardless of plan design[5]. Some insurers are managing affordability by discontinuing costly coverage—such as GLP-1 weight-loss medications—to reduce premium rate increases for broader plan members[5].

-

Detroit, MI6 days ago

Detroit, MI6 days ago2 hospitalized after shooting on Lodge Freeway in Detroit

-

Technology4 days ago

Technology4 days agoPower bank feature creep is out of control

-

Dallas, TX5 days ago

Dallas, TX5 days agoDefensive coordinator candidates who could improve Cowboys’ brutal secondary in 2026

-

Health6 days ago

Health6 days agoViral New Year reset routine is helping people adopt healthier habits

-

Iowa3 days ago

Iowa3 days agoPat McAfee praises Audi Crooks, plays hype song for Iowa State star

-

Dallas, TX1 day ago

Dallas, TX1 day agoAnti-ICE protest outside Dallas City Hall follows deadly shooting in Minneapolis

-

Nebraska3 days ago

Nebraska3 days agoOregon State LB transfer Dexter Foster commits to Nebraska

-

Nebraska3 days ago

Nebraska3 days agoNebraska-based pizza chain Godfather’s Pizza is set to open a new location in Queen Creek