Science

A total eclipse is more than a spectacle. So I'm on the road to see it — again

With the probable exception of glimpsing Earthrise out the window of Apollo 8, a total solar eclipse may be the best show in the universe accessible to human eyes.

I didn’t quite understand this seven years ago when I drove 900 miles all night and into morning from L.A. to Idaho the last time a total eclipse visited North America.

But what I saw then has set me on the road again, by plane and car to St. Louis, with plans to venture southeast for Monday’s eclipse.

The allure is not just the spectacle of this astronomical rarity. A partial solar eclipse, as will be visible Monday from Los Angeles and the rest of the contiguous United States — weather permitting — is a marvel not to be missed. But I am not traveling halfway across the country just to see a partial eclipse gone total.

I am going to watch the sun turn into a platypus.

At the instant the lunar disk slips entirely over the solar disk, the sun is abruptly transfigured into a foreign object. As if you looked at your watch and it suddenly turned into a flower.

Those lovely eclipse photos of a brilliant white halo (the solar corona, visible only during an eclipse) surrounding the deep black lunar sphere are poor preparation for the event. As I looked up from an Idaho Falls roadside lot in August 2017, at the moment of total eclipse the sun was no longer the sun.

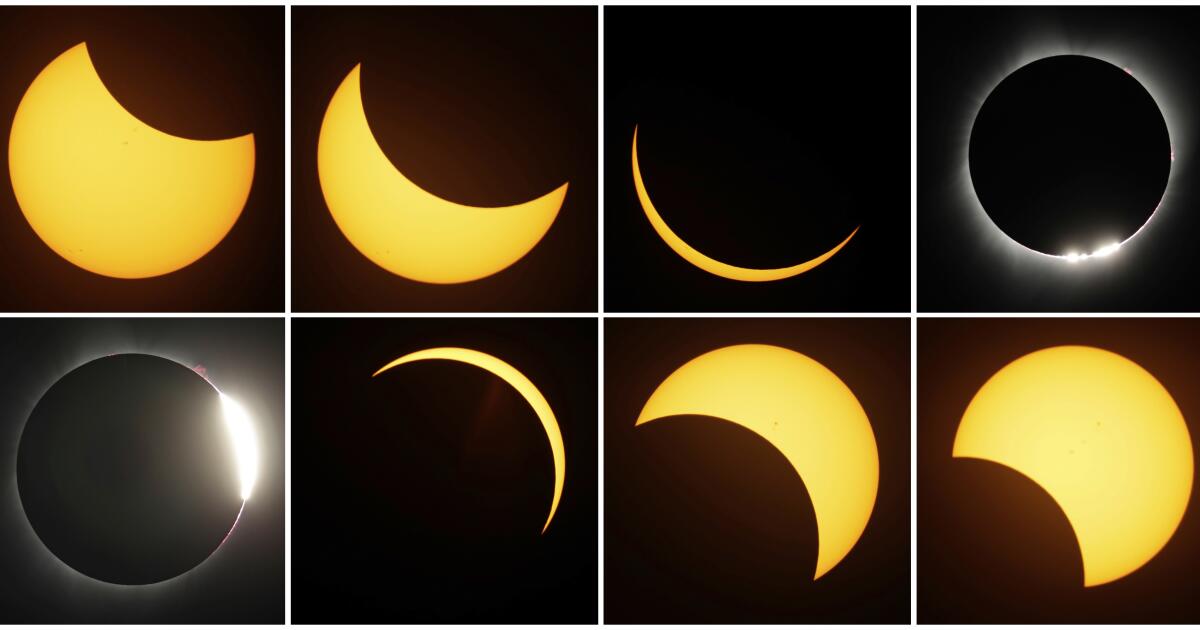

This combination of photos shows the progression of the eclipse of Aug. 21, 2017, near Redmond, Ore.

(Ted S. Warren / Associated Press)

I felt as I imagine the bemused European naturalists must have when, in 1799, they beheld for the first time a platypus specimen, a creature they found so peculiar they initially declared it an Australian hoax. What I saw above Idaho was neither fish nor fowl, and I could not quite convince myself it was real.

“In the sky was something that should not be there,” Annie Dillard wrote in her essay on seeing the moon obliterate the sun near Yakima, Wash., in 1979. In her view, this was not a good thing. “I pray you will never see anything more awful in the sky.”

In the sky was something that should not be there

— Annie Dillard, on the 1979 eclipse

When 38 years later I witnessed the next total solar eclipse viewable from the United States, I too was shaken, though in a very different way.

The moment of “totality,” as it’s called in astronomy lingo, issues a shock to the system, as if one were plunged into an ice cold pond. Day fades and then suddenly — snap! — flips to night, or twilight at least. Temperature falls, the wind rises. Stars and planets alight on their evening perches. Twilight too is total — 360 degrees: On any horizon can be seen the familiar orange glow we associate with sunrise or sunset.

I was literally breathless. I gasped to recover my lungs’ normal function. Voices around me exclaimed, with variations of “oh-my-God” or “holy” punctuated with swear words of choice.

In my usual job as a copy editor for this newspaper, I tend to cast a skeptical eye on a writer’s use of the word “ecstatic.” I can confirm that when it comes to watching a total eclipse, the word is warranted.

Though we moderns stand on the terra firma of scientific rigor — since at least the 1st century BC, astronomers have been able to predict eclipses roughly, and with ever-greater precision since Edmond Halley in the 18th century — we can appreciate how a total eclipse must’ve scared the devil out of the ancients.

Mythology is filled with apocalyptic visions associated with eclipses. They appear as ill omens in Shakespeare and, of course, the Bible. Milton summed it up in “Samson Agonistes”: “Oh dark, dark, dark, amid the blaze of noon, / Irrecoverably dark, total Eclipse / Without all hope of day!”

Christopher Columbus used his foreknowledge of a lunar eclipse to force the Arawak residents of present-day Jamaica to heel in fear in 1504.

(Frederic Lewis / Getty Images)

So terrified were the warring Lydians and Medes at the arrival of an eclipse in 585 BC, Herodotus tells us, they immediately made peace. Columbus used his foreknowledge of a lunar eclipse to force the Arawak residents of present-day Jamaica to heel in fear. As late as the 19th century, a solar eclipse over Virginia inspired Nat Turner to launch his violent uprising. The 1878 eclipse in the U.S. aroused fears of Armageddon, moving one man to kill his young son with an ax and slit his own throat. The acclaimed essay by Dillard, a fellow modern, is a doomscape of terror and death.

I find a total solar eclipse to be an affirmation of humanity, both as experience and as a triumph of knowledge over the glare of ignorance. Eclipses were once crucial in producing more accurate land and sea maps, and they inform solar science to this day. English astronomer Arthur Eddington’s eclipse expedition of 1919 proved Einstein’s theory of general relativity beyond a shadow of a doubt.

At the instant of totality, planetary motion as described by Newton and Kepler is not a matter only for scientists and our imaginations. It is something to be seen and felt by anyone in the right place at the right time. Our moon is orbiting us; the sphere on which we stand is also in motion, on its daily axis and annually lapping the sun. It is one thing to know and understand this; it is another to experience it.

Our everyday illusions are exposed as counterfeit: of a sky above, when in fact sky is all around us; of the sun rising and setting, when it does no such thing; of a moon waxing and waning, when it is continuously circling us with its same face forward. “We are an impossibility in an impossible universe,” author Ray Bradbury said.

And just what is this cosmic platypus, this something in the sky that should not be there? Similes abound.

A total eclipse of the sun is said to look like a black dahlia or a monochrome sunflower. Or a hole punched in the sky.

I prefer to think of it as a Louise Nevelson sculpture suspended above.

Many of Nevelson’s well-known works of the 1950s to 1970s were monochromatic black. Influenced by the space exploration of her time, the artist suggested celestial objects in her sculptures and chose titles featuring “night,” “sky,” “lunar,” “moon.” On at least one occasion, she took inspiration from astronaut Bill Anders’ “Earthrise” photo of 1968.

Her sculptures were, perhaps most of all, a meditation on the color black.

During a total eclipse, the sun’s blazing corona and “diamond ring” of light oozing outside the lunar disk just before and after totality are the main spectacle. But I was just as transfixed by the absolute blackness of the moon within. It is almost certainly the blackest black possible.

“I fell in love with black; it contained all color,” Nevelson once explained. “It wasn’t a negation of color. It was an acceptance. Because black encompasses all colors.” Black, for Nevelson, was “the total color. It means totality. It means: contain all.”

That is the lunar black I saw over Idaho Falls and which draws me now to Missouri. The title of a celebrated series of Nevelson works, “Sky Cathedral,” would do well as a name for nature’s occasional exhibition of lunar-solar art.

The 2024 eclipse arrives at a grim time in our history. We have witnessed the worst pandemic in a century. Gun violence at home and excruciating wars abroad seem impossibly intractable. Climate denial imperils our existence and a pernicious relativism our democracy. My profession and my newspaper, proudly committed to separating facts from fabrication, are at a crossroads of sustainability.

So a few minutes of astronomical truth seem all the more necessary for me to revisit at this time, though now with better preparation.

In 2017 I embarked on my all-night drive to see the eclipse out of last-minute inspiration. As an avid sky-watcher, I had an obvious interest. Not yet knowing what I was in for, though, I dawdled, thinking the journey too far and impractical, until I finally relented about 20 hours before totality over Idaho. I arrived with hours to spare under propitious skies.

I regretted my lack of planning on the way back, when I endured a traffic doomsday on Interstate 15 and could find no hotel vacancy along the route south before I finally gave up and slept in my car.

My eclipse preparations this time have been more considered and considerable, though complicated.

An early plan for an eclipse viewing in Rochester, N.Y., fell through. In the meantime, I have assembled a small library of eclipse books and magazines, including a road atlas that superimposes the 2024 path of totality onto a detailed map of the U.S., Mexico and Canada.

I considered joining the eclipse crowds in Carbondale, Ill., where a news report on Atlas Obscura said that old-time apocalyptic fever — also known as modern-day conspiracy theorist hokum — had taken hold.

Bob Baer of Southern Illinois University in Carbondale, co-chair of the Southern Illinois Eclipse 2017-2024 Steering Committee, will be leading a comprehensive monitoring effort to capture Monday’s solar eclipse moment by moment.

(Carlos Javier Ortiz / Getty Images)

Because Carbondale happened to be in the path of totality in 2017 and is so again in 2024, it seems many believed Monday’s eclipse encore would trigger a calamitous seismic event in town. This disturbing local opinion suggested to me an intriguing juxtaposition of setting for my notion of affirming the reality of our shared universe under the shadow of the moon.

The prime spot seemed to be southern Texas. Historical weather records indicate that the path through Texas had a much greater likelihood of cloud-free skies than farther northeast. And the duration of totality near the path’s center line was due to be almost 4½ minutes. As this eclipse moves northeast, its duration will get shorter, its path narrower.

Monday’s total eclipse will arrive on Mexico’s Pacific coast, climb through Texas and Arkansas, then cross the Midwest and New England before exiting over eastern Canada into the Atlantic.

(Associated Press)

In Idaho Falls, totality lasted about 1 minute and 40 seconds. Four and a half minutes over Texas? I could hardly fathom it. I made plans for San Antonio.

Until the actual meteorological forecast defied historical prediction. As eclipse day drew near, “weather permitting” turned more ominous. Less than a week out, the April 8 forecast for Texas — nearly the entire state, apparently — called for overcast skies all day, maybe even thunderstorms.

I studied my alternatives. Flights were still reasonable to Chicago, from where I could drive a few hours to reach several cities along the path: Indianapolis, Cleveland, even Buffalo. I also considered Mexico, but the forecast for the whole of its eclipse path, from Mazatlán to the border town of Piedras Negras, was likewise dire.

I added 16 cities to my phone’s weather app, from Mazatlán to Buffalo, which I monitored as the 8th drew near. Days before my planned departure, I booked accommodations in St. Louis, two hours from the center line.

The weather may yet conspire against me, and 3 or 4 minutes of totality will be lost under a ceiling of clouds. If so, I will see something I never have before. The midday gray blackening, then brightening, on account of a remote and veiled disk of sun and moon.

Astronaut Bill Anders snapped his “Earthrise” photo from the window of Apollo 8 on Dec. 24, 1968.

(NASA)

Either way, Bradbury advised, we are obliged to keep watch:

Why have we been put here? … There’s no use having a universe … there’s no use having a billion stars, there’s no use having a planet Earth if there isn’t someone here to see it. You are the audience. You are here to witness and celebrate. And you’ve got a lot to see and a lot to celebrate.

Science

Shark attacks rose in 2025. Here’s why Californians should take note

Shark attacks returned to near-average levels in 2025 after a dip the previous year, according to the latest report from the Florida Museum of Natural History’s International Shark Attack File, published Wednesday.

Researchers recorded 65 unprovoked shark bites worldwide last year, slightly below the 10-year average of 72, but an increase from 2024. Nine of those bites were fatal, higher than the 10-year average of six fatalities.

The United States once again had the highest number of reported incidents, accounting for 38% of global unprovoked bites when assessed on a country by country basis. That said, it’s actually a decline from recent years, including 2024, when more than half of all reported bites worldwide occurred off the U.S. coast.

In 2025, Florida led all states with 11 recorded attacks. California, Hawaii, Texas and North Carolina accounted for the remaining U.S. incidents.

But California stood out in another way: It had the nation’s only unprovoked fatal shark attack in 2025.

A 55-year-old triathlete was attacked by a white shark after entering the water off the coast of Monterey Bay with members of the open-ocean swimming club she co-founded. It was the sole U.S. fatality among 25 reported shark bites nationwide.

It’s not surprising that the sole U.S. shark-related death occurred in California, said Steve Midway, an associate professor of fisheries at Louisiana State University. “In California, you tend to have year-to-year fewer attacks than other places in the U.S. and in the world,” Midway said. “But you tend to have more serious attacks, a higher proportion of fatal attacks.”

The difference lies in species and geography, Midway said. Along the East Coast, particularly in Florida, many bites involve smaller coastal sharks in shallow water, which are more likely to result in nonfatal injuries. California’s deeper and colder waters are home to larger species, such as the great white shark.

“Great whites just happen to be larger,” Midway said. “You’re less likely to be attacked, but if you are, the outcomes tend to be worse.”

Whether measured over 10, 20 or 30 years, average annual shark bite totals globally are actually very stable.

“The global patterns change only slightly from one year to the other,” said Gavin Naylor, director of the Florida Program for Shark Research.

Those annual fluctuations are influenced by a combination of shark biology, ocean conditions and the number of people in the water at any given time in any given place, researchers say.

At the same time, global shark populations remain far below historical levels. Naylor categorizes about 30% of shark species as endangered, largely due to overfishing. In some countries, including the United States and Australia, stronger protections have allowed certain shark populations to recover.

Nevertheless, the risk of being bitten by a shark remains extremely low. The report notes that drowning is a far more common cause of death worldwide — and, if it helps you sleep (or swim), the data show that you are much more likely to be killed by lightning than you are by a shark.

Science

What a Speech Reveals About Trump’s Plans for Nuclear Weapons

Within hours of the expiration last week of the final arms control treaty between Moscow and Washington, the State Department sent its top arms diplomat, Thomas G. DiNanno, to Geneva to lay out Washington’s vision for the future. His public address envisioned a future filled with waves of nuclear arms buildups and test detonations.

The views of President Trump’s administration articulated in Mr. DiNanno’s speech represent a stark break with decades of federal policy. In particular, deep in the speech, he describes a U.S. rationale for going its own way on the global ban on nuclear test detonations, which had been meant to curb arms races that in the Cold War had raised the risk of miscalculation, and war.

This annotation of the text of his remarks aims to offer background information on some of the specialized language of nuclear policymaking that Mr. DiNanno used to make his points, while highlighting places where outside experts may disagree with his and the administration’s claims.

What remains unknown is the extent to which Mr. DiNanno’s presentation represents a fixed policy of unrestrained U.S. arms buildups, or more of an open threat meant to spur negotiations toward new global accords on ways to better manage the nuclear age.

Read the original speech.

New York Times Analysis

Next »

1

Established in 1979 as Cold War arsenals grew worldwide, the Conference on Disarmament is a United Nations arms reduction forum made up of 65 member states. It has helped the world negotiate and adopt major arms agreements.

2

In his State Department role, working under Secretary of State Marco Rubio, Mr. DiNanno is Washington’s top diplomat for the negotiation and verification of international arms accords. Past holders of that office include John Bolton during the first term of the George W. Bush administration and Rose Gottemoeller during Barack Obama’s two terms.

3

This appears to be referring to China, which has 600 nuclear weapons today. By 2030, U.S. intelligence estimates say it will have more than 1,000.

4

Here he means Russia, which is conducting tests to put a nuclear weapon into space as well as to develop an underwater drone meant to cross oceans.

New York Times Analysis

« Previous Next »

5

In this year’s federal budget, the Trump administration is to spend roughly $90 billion on nuclear arms, including basic upgrades of the nation’s arsenal and the replacement of aging missiles, bombers and submarines that can deliver warheads halfway around the globe.

6

A chief concern of many American policymakers is that Washington will soon face not just a single peer adversary, as in the Cold War, but two superpower rivals, China and Russia.

New York Times Analysis

« Previous Next »

7

The 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty or I.N.F. banned all weapons capable of traveling between 500 and 5,500 kilometers, or 310 and 3,420 miles, whether armed with nuclear or conventional warheads. The Trump administration is now deploying a number of conventionally armed weapons in that range, including a cruise missile and a hypersonic weapon.

8

The destructive force of the relatively small Russian arms can be just fractions of the Hiroshima bomb’s power, perhaps making their use more likely. The lesser warheads are known as tactical or nonstrategic nuclear arms, and President Vladimir V. Putin of Russia has repeatedly threatened to use them in Ukraine.

9

Negotiators of arms control treaties have mostly focused on long-range weapons because the delivery vehicles and their deadly warheads are considered planet shakers that could end civilization.

New York Times Analysis

« Previous Next »

10

This underwater Russian craft is meant to cross an ocean, detonate a thermonuclear warhead and raise a radioactive tsunami powerful enough to shatter a coastal city.

11

The nuclear power source of this Russian weapon can in theory keep the cruise missile airborne far longer than other nuclear-armed missiles.

12

Russia has conducted test launches for placing a nuclear weapon into orbit, which the Biden administration quietly warned Congress about two years ago.

13

The term refers to the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council—China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States.

New York Times Analysis

« Previous Next »

14

A top concern of American officials is that Beijing and Moscow might form an alliance to coordinate their nuclear forces. Their joint program to develop fuel for atom bombs is seen as an indication of this emerging threat.

15

This Trump administration plan is dated November but was made public in December.

16

Released last year, this Chinese government document sought to portray Beijing as a leader in reducing the global threat of nuclear weapons.

17

Typically, arms control treaties have not required countries to destroy warheads so their keepers put them into storage for possible reuse. The United States retains something on the order of 20,000 small atom bombs meant to ignite the larger blasts of hydrogen bombs.

18

An imminent surge centers on the nation’s Ohio-class submarines. The Trump administration has called for the reopening of submarine missile tubes that were closed to comply with the New START limits. That will add as many 56 long-range missiles to the fleet. Because each missile can hold multiple arms, the additional force adds up to hundreds more warheads.

19

This refers to weapons meant for use on a battlefield or within a particular geographic region rather than for aiming at distant targets. It is often seen as synonymous with intermediate-range weapons.

20

Here, the talk turns to the explosive testing of nuclear weapons for safety, reliability and devising new types of arms. The United States last conducted such a test in 1992 and afterwards adopted a policy of using such nonexplosive means like supercomputer simulations to evaluate its arsenal. In 1996, the world’s nuclear powers signed a global ban on explosive testing. A number of nations, including the United States and China, never ratified the treaty, and it never officially went into force.

21

In new detail, the talk addresses what Mr. Trump meant last fall when he declared that he had instructed the Pentagon “to start testing our Nuclear Weapons on an equal basis” in response to the technical advances of unnamed foreign states.

22

Outside experts say the central issue is not whether China and Russia are cheating on the global test ban treaty but whether they are adhering to the U.S. definition. From the treaty’s start in 1996, Washington interpreted “zero” explosive force as the compliance standard but the treaty itself gives no definition for what constitutes a nuclear explosion. Over decades, that ambiguity led to technical disputes that helped block the treaty’s ratification.

23

By definition, all nuclear explosions are supercritical, which means they split atoms in chain reactions that become self-sustaining in sufficient amounts of nuclear fuel. The reports Mr. DiNanno refers to told of intelligence data suggesting that Russia was conducting a lesser class of supercritical tests that were too small to be detected easily. Russian scientists have openly discussed such small experiments, which are seen as useful for assessing weapon safety but not for developing new types of weapons.

24

This sounds alarming but experts note that the text provides no evidence and goes on to speak of preparations, not detonations, except in one specific case.

New York Times Analysis

« Previous

25

The talk gave no clear indication of how the claims about Russian and Chinese nuclear testing might influence U.S. arms policy. But it repeated Mr. Trump’s call for testing “on an equal basis,” suggesting the United States might be headed in that direction, too.

26

The talk, however, ended on an upbeat but ambiguous note, giving no indication of what Mr. DiNanno meant by “responsible.” Even so, the remark came in the context of bilateral and multilateral actions to reduce the number of nuclear arms in the world, suggesting that perhaps the administration’s aim is to build up political leverage and spur new negotiations with Russia, China or both on testing restraints.

Science

Notoriously hazardous South L.A. oil wells finally plugged after decades of community pressure

California Gov. Gavin Newsom announced this week that state oil and gas regulators have permanently closed one of the most infamous drill sites in Los Angeles, bringing an end to a decades-long community campaign to prevent dangerous gas leaks and spills from rundown extraction equipment.

A state contractor plugged all 21 oil wells at the AllenCo Energy drill site in University Park, preventing the release of noxious gases and chemical vapors into the densely populated South Los Angeles neighborhood. The two-acre site, owned by the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, is located across the street from several multifamily apartment buildings and less than 1,000 feet from St. Vincent School.

For years, residents and students had repeatedly complained about acrid odors from the site, with many suffering chronic headaches and nosebleeds. The health concerns prompted a community-driven campaign to shut down the site, with some residents even pleading (unsuccessfully) with the late Pope Francis to intervene.

AllenCo, the site’s operator since 2009, repeatedly flouted environmental regulations and defied state orders to permanently seal its wells.

This month, the California Department of Conservation’s Geologic Energy Management Division (CalGEM) finished capping the remaining unplugged wells with help from Biden-era federal funding.

“This is a monumental achievement for the community who have endured an array of health issues and corporate stalling tactics for far too long,” Newsom said in a statement Wednesday. “I applaud the tireless work of community activists who partnered with local and state agencies to finish the job and improve the health and safety of this community. This is a win for all Californians.”

The land was donated to the Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles in the 1950s by descendants of one of the city’s early oil barons. Over the decades, the archdiocese leased the land to several oil companies including Standard Oil of California.

Much of the community outcry over the site’s management occurred after AllenCo took over the site in 2009. The company drastically boosted oil production, but failed to properly maintain its equipment, resulting in oil spills and gas leaks.

In 2013, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency officials became sick while inspecting the site. The federal investigators encountered puddles of crude oil on the facility grounds, as well as caustic fumes emanating from the facility, resulting in violations for air quality and other environmental infractions.

In 2020, CalGEM ordered AllenCo to plug the wells after if determined the company had essentially deserted the site, leaving the wells unplugged and in an unsafe condition. AllenCo ignored the order.

In perhaps the most remarkable events in the site’s history, CalGEM officials in 2022 arrived on the site with a court order and used bolt cutters to enter the site to depressurize the poorly maintained oil wells.

The AllenCo wells were prioritized and plugged this week as part of a CalGEM program to identify and permanently cap high-risk oil and gas wells. Tens of thousands of unproductive and unplugged oil wells have been abandoned across California — many of which continue to leak potentially explosive methane or toxic benzene.

Environmental advocates have long fought for regulators to require oil and gas companies to plug these wells to protect nearby communities and the environment.

However, as oil production declines and fossil fuel companies increasingly become insolvent, California regulators worry taxpayers may have to assume the costs to plug these wells. Federal and state officials have put aside funding to deal with some of these so-called “orphaned” wells, but environmental advocates say it’s not enough. They say oil and gas companies still need to be held to account, so that the same communities that were subjected to decades of pollution won’t have to foot the bill for expensive cleanups.

“This is welcome news that the surrounding community deserves, but there is much more work to be done at a much faster pace,” said Cooper Kass, attorney at the Center for Biological Diversity’s Climate Law Institute. “There are still thousands of unplugged and hazardous idle wells threatening communities across the state, and our legislators and regulators should force polluters, not taxpayers, to pay to clean up these dangerous sites.”

-

Culture1 week ago

Culture1 week agoTry This Quiz on Passionate Lines From Popular Literature

-

Oklahoma2 days ago

Oklahoma2 days agoWildfires rage in Oklahoma as thousands urged to evacuate a small city

-

Health1 week ago

Health1 week agoJames Van Der Beek shared colorectal cancer warning sign months before his death

-

![“Redux Redux”: A Mind-Blowing Multiverse Movie That Will Make You Believe in Cinema Again [Review] “Redux Redux”: A Mind-Blowing Multiverse Movie That Will Make You Believe in Cinema Again [Review]](https://i1.wp.com/www.thathashtagshow.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/Redux-Redux-Review.png?w=400&resize=400,240&ssl=1)

![“Redux Redux”: A Mind-Blowing Multiverse Movie That Will Make You Believe in Cinema Again [Review] “Redux Redux”: A Mind-Blowing Multiverse Movie That Will Make You Believe in Cinema Again [Review]](https://i1.wp.com/www.thathashtagshow.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/Redux-Redux-Review.png?w=80&resize=80,80&ssl=1) Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week ago“Redux Redux”: A Mind-Blowing Multiverse Movie That Will Make You Believe in Cinema Again [Review]

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoHP ZBook Ultra G1a review: a business-class workstation that’s got game

-

Science1 week ago

Science1 week agoA SoCal beetle that poses as an ant may have answered a key question about evolution

-

Politics7 days ago

Politics7 days agoCulver City, a crime haven? Bondi’s jab falls flat with locals

-

Politics7 days ago

Politics7 days agoTim Walz demands federal government ‘pay for what they broke’ after Homan announces Minnesota drawdown