Science

A total eclipse is more than a spectacle. So I'm on the road to see it — again

With the probable exception of glimpsing Earthrise out the window of Apollo 8, a total solar eclipse may be the best show in the universe accessible to human eyes.

I didn’t quite understand this seven years ago when I drove 900 miles all night and into morning from L.A. to Idaho the last time a total eclipse visited North America.

But what I saw then has set me on the road again, by plane and car to St. Louis, with plans to venture southeast for Monday’s eclipse.

The allure is not just the spectacle of this astronomical rarity. A partial solar eclipse, as will be visible Monday from Los Angeles and the rest of the contiguous United States — weather permitting — is a marvel not to be missed. But I am not traveling halfway across the country just to see a partial eclipse gone total.

I am going to watch the sun turn into a platypus.

At the instant the lunar disk slips entirely over the solar disk, the sun is abruptly transfigured into a foreign object. As if you looked at your watch and it suddenly turned into a flower.

Those lovely eclipse photos of a brilliant white halo (the solar corona, visible only during an eclipse) surrounding the deep black lunar sphere are poor preparation for the event. As I looked up from an Idaho Falls roadside lot in August 2017, at the moment of total eclipse the sun was no longer the sun.

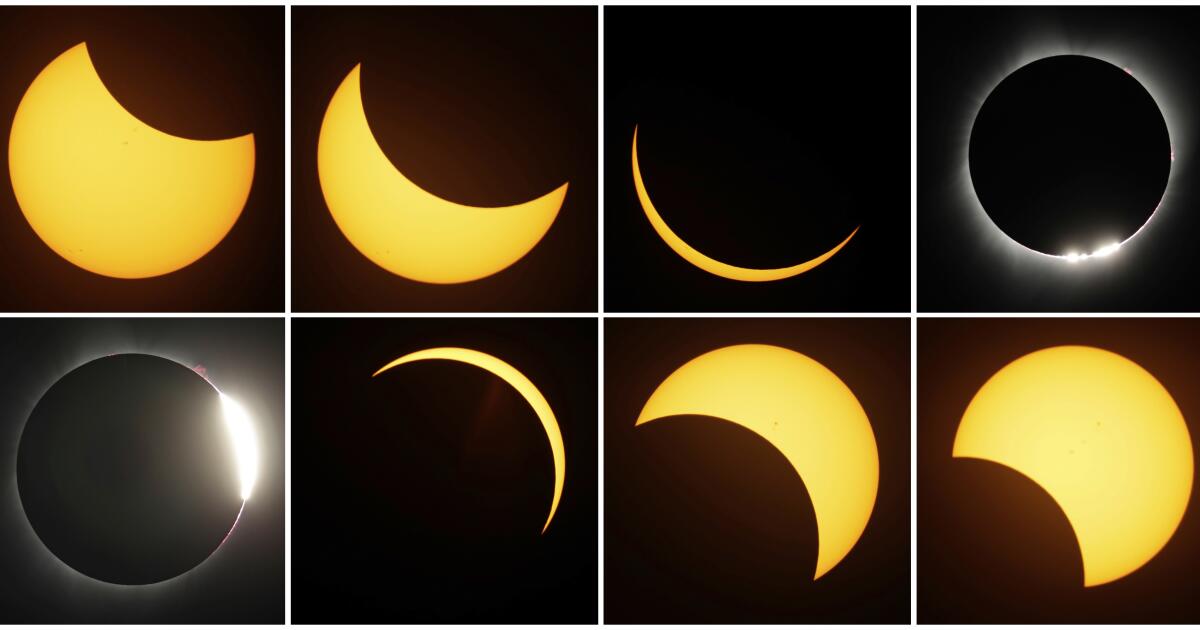

This combination of photos shows the progression of the eclipse of Aug. 21, 2017, near Redmond, Ore.

(Ted S. Warren / Associated Press)

I felt as I imagine the bemused European naturalists must have when, in 1799, they beheld for the first time a platypus specimen, a creature they found so peculiar they initially declared it an Australian hoax. What I saw above Idaho was neither fish nor fowl, and I could not quite convince myself it was real.

“In the sky was something that should not be there,” Annie Dillard wrote in her essay on seeing the moon obliterate the sun near Yakima, Wash., in 1979. In her view, this was not a good thing. “I pray you will never see anything more awful in the sky.”

In the sky was something that should not be there

— Annie Dillard, on the 1979 eclipse

When 38 years later I witnessed the next total solar eclipse viewable from the United States, I too was shaken, though in a very different way.

The moment of “totality,” as it’s called in astronomy lingo, issues a shock to the system, as if one were plunged into an ice cold pond. Day fades and then suddenly — snap! — flips to night, or twilight at least. Temperature falls, the wind rises. Stars and planets alight on their evening perches. Twilight too is total — 360 degrees: On any horizon can be seen the familiar orange glow we associate with sunrise or sunset.

I was literally breathless. I gasped to recover my lungs’ normal function. Voices around me exclaimed, with variations of “oh-my-God” or “holy” punctuated with swear words of choice.

In my usual job as a copy editor for this newspaper, I tend to cast a skeptical eye on a writer’s use of the word “ecstatic.” I can confirm that when it comes to watching a total eclipse, the word is warranted.

Though we moderns stand on the terra firma of scientific rigor — since at least the 1st century BC, astronomers have been able to predict eclipses roughly, and with ever-greater precision since Edmond Halley in the 18th century — we can appreciate how a total eclipse must’ve scared the devil out of the ancients.

Mythology is filled with apocalyptic visions associated with eclipses. They appear as ill omens in Shakespeare and, of course, the Bible. Milton summed it up in “Samson Agonistes”: “Oh dark, dark, dark, amid the blaze of noon, / Irrecoverably dark, total Eclipse / Without all hope of day!”

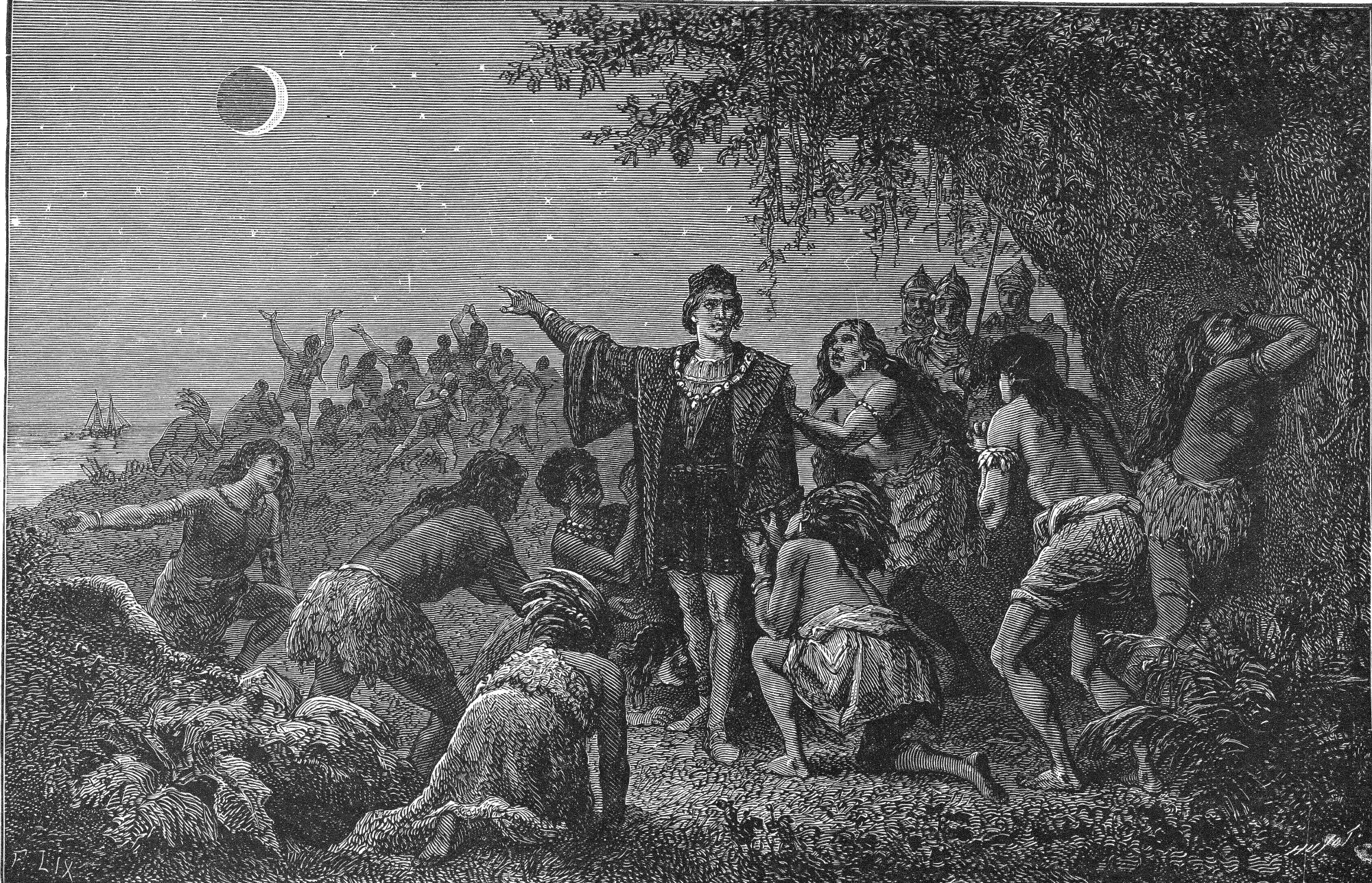

Christopher Columbus used his foreknowledge of a lunar eclipse to force the Arawak residents of present-day Jamaica to heel in fear in 1504.

(Frederic Lewis / Getty Images)

So terrified were the warring Lydians and Medes at the arrival of an eclipse in 585 BC, Herodotus tells us, they immediately made peace. Columbus used his foreknowledge of a lunar eclipse to force the Arawak residents of present-day Jamaica to heel in fear. As late as the 19th century, a solar eclipse over Virginia inspired Nat Turner to launch his violent uprising. The 1878 eclipse in the U.S. aroused fears of Armageddon, moving one man to kill his young son with an ax and slit his own throat. The acclaimed essay by Dillard, a fellow modern, is a doomscape of terror and death.

I find a total solar eclipse to be an affirmation of humanity, both as experience and as a triumph of knowledge over the glare of ignorance. Eclipses were once crucial in producing more accurate land and sea maps, and they inform solar science to this day. English astronomer Arthur Eddington’s eclipse expedition of 1919 proved Einstein’s theory of general relativity beyond a shadow of a doubt.

At the instant of totality, planetary motion as described by Newton and Kepler is not a matter only for scientists and our imaginations. It is something to be seen and felt by anyone in the right place at the right time. Our moon is orbiting us; the sphere on which we stand is also in motion, on its daily axis and annually lapping the sun. It is one thing to know and understand this; it is another to experience it.

Our everyday illusions are exposed as counterfeit: of a sky above, when in fact sky is all around us; of the sun rising and setting, when it does no such thing; of a moon waxing and waning, when it is continuously circling us with its same face forward. “We are an impossibility in an impossible universe,” author Ray Bradbury said.

And just what is this cosmic platypus, this something in the sky that should not be there? Similes abound.

A total eclipse of the sun is said to look like a black dahlia or a monochrome sunflower. Or a hole punched in the sky.

I prefer to think of it as a Louise Nevelson sculpture suspended above.

Many of Nevelson’s well-known works of the 1950s to 1970s were monochromatic black. Influenced by the space exploration of her time, the artist suggested celestial objects in her sculptures and chose titles featuring “night,” “sky,” “lunar,” “moon.” On at least one occasion, she took inspiration from astronaut Bill Anders’ “Earthrise” photo of 1968.

Her sculptures were, perhaps most of all, a meditation on the color black.

During a total eclipse, the sun’s blazing corona and “diamond ring” of light oozing outside the lunar disk just before and after totality are the main spectacle. But I was just as transfixed by the absolute blackness of the moon within. It is almost certainly the blackest black possible.

“I fell in love with black; it contained all color,” Nevelson once explained. “It wasn’t a negation of color. It was an acceptance. Because black encompasses all colors.” Black, for Nevelson, was “the total color. It means totality. It means: contain all.”

That is the lunar black I saw over Idaho Falls and which draws me now to Missouri. The title of a celebrated series of Nevelson works, “Sky Cathedral,” would do well as a name for nature’s occasional exhibition of lunar-solar art.

The 2024 eclipse arrives at a grim time in our history. We have witnessed the worst pandemic in a century. Gun violence at home and excruciating wars abroad seem impossibly intractable. Climate denial imperils our existence and a pernicious relativism our democracy. My profession and my newspaper, proudly committed to separating facts from fabrication, are at a crossroads of sustainability.

So a few minutes of astronomical truth seem all the more necessary for me to revisit at this time, though now with better preparation.

In 2017 I embarked on my all-night drive to see the eclipse out of last-minute inspiration. As an avid sky-watcher, I had an obvious interest. Not yet knowing what I was in for, though, I dawdled, thinking the journey too far and impractical, until I finally relented about 20 hours before totality over Idaho. I arrived with hours to spare under propitious skies.

I regretted my lack of planning on the way back, when I endured a traffic doomsday on Interstate 15 and could find no hotel vacancy along the route south before I finally gave up and slept in my car.

My eclipse preparations this time have been more considered and considerable, though complicated.

An early plan for an eclipse viewing in Rochester, N.Y., fell through. In the meantime, I have assembled a small library of eclipse books and magazines, including a road atlas that superimposes the 2024 path of totality onto a detailed map of the U.S., Mexico and Canada.

I considered joining the eclipse crowds in Carbondale, Ill., where a news report on Atlas Obscura said that old-time apocalyptic fever — also known as modern-day conspiracy theorist hokum — had taken hold.

Bob Baer of Southern Illinois University in Carbondale, co-chair of the Southern Illinois Eclipse 2017-2024 Steering Committee, will be leading a comprehensive monitoring effort to capture Monday’s solar eclipse moment by moment.

(Carlos Javier Ortiz / Getty Images)

Because Carbondale happened to be in the path of totality in 2017 and is so again in 2024, it seems many believed Monday’s eclipse encore would trigger a calamitous seismic event in town. This disturbing local opinion suggested to me an intriguing juxtaposition of setting for my notion of affirming the reality of our shared universe under the shadow of the moon.

The prime spot seemed to be southern Texas. Historical weather records indicate that the path through Texas had a much greater likelihood of cloud-free skies than farther northeast. And the duration of totality near the path’s center line was due to be almost 4½ minutes. As this eclipse moves northeast, its duration will get shorter, its path narrower.

Monday’s total eclipse will arrive on Mexico’s Pacific coast, climb through Texas and Arkansas, then cross the Midwest and New England before exiting over eastern Canada into the Atlantic.

(Associated Press)

In Idaho Falls, totality lasted about 1 minute and 40 seconds. Four and a half minutes over Texas? I could hardly fathom it. I made plans for San Antonio.

Until the actual meteorological forecast defied historical prediction. As eclipse day drew near, “weather permitting” turned more ominous. Less than a week out, the April 8 forecast for Texas — nearly the entire state, apparently — called for overcast skies all day, maybe even thunderstorms.

I studied my alternatives. Flights were still reasonable to Chicago, from where I could drive a few hours to reach several cities along the path: Indianapolis, Cleveland, even Buffalo. I also considered Mexico, but the forecast for the whole of its eclipse path, from Mazatlán to the border town of Piedras Negras, was likewise dire.

I added 16 cities to my phone’s weather app, from Mazatlán to Buffalo, which I monitored as the 8th drew near. Days before my planned departure, I booked accommodations in St. Louis, two hours from the center line.

The weather may yet conspire against me, and 3 or 4 minutes of totality will be lost under a ceiling of clouds. If so, I will see something I never have before. The midday gray blackening, then brightening, on account of a remote and veiled disk of sun and moon.

Astronaut Bill Anders snapped his “Earthrise” photo from the window of Apollo 8 on Dec. 24, 1968.

(NASA)

Either way, Bradbury advised, we are obliged to keep watch:

Why have we been put here? … There’s no use having a universe … there’s no use having a billion stars, there’s no use having a planet Earth if there isn’t someone here to see it. You are the audience. You are here to witness and celebrate. And you’ve got a lot to see and a lot to celebrate.

Science

Commentary: A candid take on mortality and the power of friendship

They gather several times a week in the parking lot of a Vons supermarket in Mar Vista, and no subject is off-limits. Not even the grim medical prognosis for 70-year-old David Mays, one of the founding members of the coffee klatch.

“It’s one of our major topics of conversation,” said Paul Morgan, 45, a klatch regular.

Mays is a cancer survivor with a full package of maladies, including diabetes, a faltering heart and failing kidneys. But since I met him almost two years ago, he has told me repeatedly that he doesn’t want dialysis treatment, even though it might extend his life.

“I get it, because it’s a lot of hours out of your day,” said Morgan, a schoolteacher who lives nearby. “People think you go in for dialysis for 15 minutes before you go straight to work. But really, it’s a part-time job.”

Steve Lopez

Steve Lopez is a California native who has been a Los Angeles Times columnist since 2001. He has won more than a dozen national journalism awards and is a four-time Pulitzer finalist.

His treatment would require that he visit a dialysis center three times a week, for four hours each time, Mays said.

“For the rest of my life.”

“I don’t think I could do it,” said klatcher Kit Bradley, 70, who lives in a van near the supermarket with his dog, Lea.

I met Mays in October 2023, when he was living in his Chevy Malibu in a downtown garage that was part of the Safe Parking L.A. program. Mays later moved into an apartment in East Hollywood and still lives there, but his health has continued to deteriorate.

“He is Stage 5,” said Dr. Thet Thet Aung, Mays’ nephrologist at Kaiser Permanente West Los Angeles.

David Mays, center, enjoys a morning get-together with Paul Morgan, left, and Kit Bradley in a Vons parking lot in West Los Angeles on June 25, 2025.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

For such patients, Aung said, death can be imminent. She told me she’s had many conversations with Mays about his treatment options, including dialysis in a clinic or self-administered at home. But not everyone does well on dialysis, she added, and when a patient makes an informed choice, “we respect their wishes.”

Mays has a refreshingly healthy attitude about mortality. Multibillion-dollar industries cater to those who want to look younger and live longer, and about 25% of Medicare’s massive outlay is spent on patients in the last year of life, many of whom choose life-extending medical procedures.

Mays, in the time I’ve known him, has been realistic rather than fatalistic. He has told me he doesn’t think bravery, faith or spirituality has anything to do with his desire to let nature take its course.

“It transcends those things,” he said.

He’s at peace with his fate, he explained, because he’s got friends, love and support.

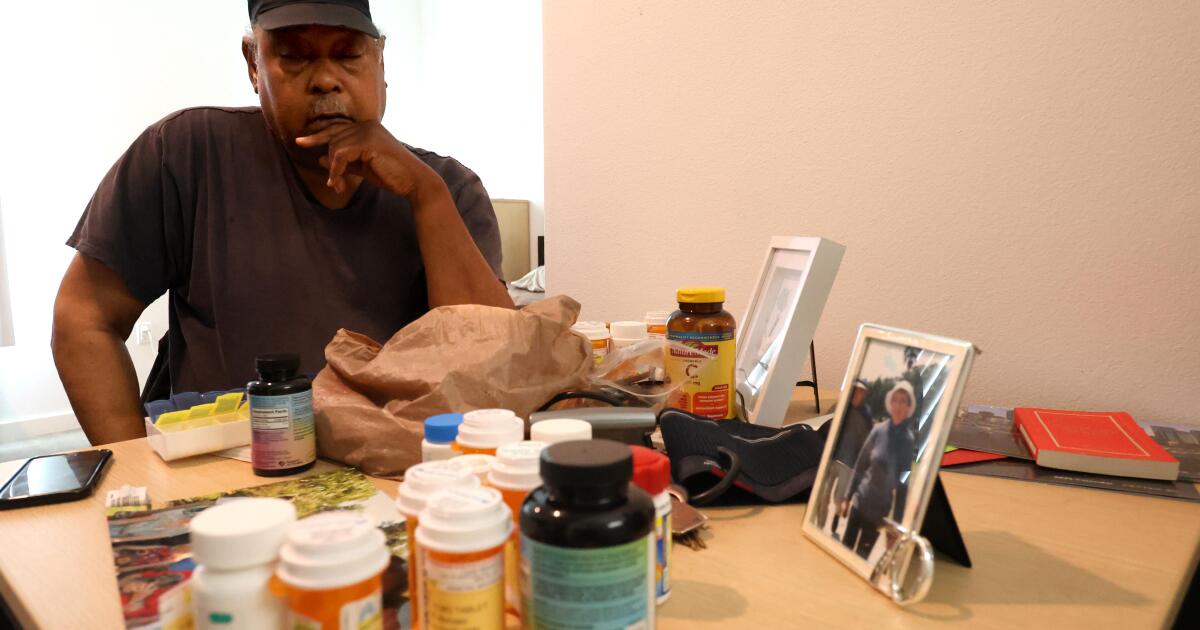

On a recent day at his apartment, I watched Mays load medication from more than 20 vials into a weekly pill organizer.

“I could almost do this in my sleep,” he said as he arranged meds that resembled miniature jelly beans. This one for his kidneys, that one for his heart, his blood pressure, and on and on.

Bottles of medication and photos of close friends rest on David Mays’ table at his apartment in East Hollywood.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

There were 18 pills in each compartment. And none of that will cure any of what ails him, he said.

“You just have to keep doing it, and doing it, just to stay at a sustained level,” he said. “It’s not like … I feel great because I took this stuff.”

Two women in Mays’ life are heartbroken about his condition but respectful of his refusal to try dialysis.

“I don’t want him to suffer for the sake of placating other people,” said Mays’ daughter Jennifer Nutt, 47, of Merced.

Her parents divorced when she and her brother were young, and Nutt had no relationship with Mays until recently. She’s had her own trials, Nutt said, including homelessness.

Father and daughter began connecting in the fall of 2024.

“We spend hours every day talking. It’s like a nonstop festival of catching up,” and they’ve discovered they have the same cheeky sense of humor and pragmatism, and similar traits and interests.

“We like big words and thick books,” Nutt said.

The other woman is Helena Bake, of Perth, Australia, a registered nurse Mays affectionately refers to as “Precious.” They met in 1985, when Mays was visiting London, and Bake, 18 at the time, was working in a restaurant he visited with friends. After Bake moved to Australia, Mays visited her many times and became close to her entire family.

“He was lovely,” said Bake, who is not surprised by Mays’ attitude about his deteriorating health. “He’s always very positive and so pragmatic. He has this wonderful view of the world and the people in his life. It’s such a gift that he has.”

Mays, who gets by on Social Security payments, has set up a GoFundMe page to help pay for his cremation and send his ashes to Bake, to be scattered in his favorite places in Australia.

Lately, medical appointments with his several doctors, and the occasional ER visit, have gotten in the way of one of Mays’ favorite activities — the gatherings in the Vons parking lot.

David Mays is “always very positive and so pragmatic. He has this wonderful view of the world and the people in his life. It’s such a gift that he has,” a longtime friend says.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

Mays worked for many years in the Mar Vista area as a live-in elder care provider, and he’d bump into Bradley at a park, or Morgan in the strip mall that includes the grocery store. Several years ago, they made a habit of grabbing coffee around 7 a.m. and hanging out near Mays’ car. Bradley’s dog often hops into the vehicle, a Vons employee named Elvis comes out for a smoke break, and others come and go.

“I had a cousin who had diabetes, and he called my mom one day and said, ‘I’m not doing it anymore,’ ” Morgan was saying the other day. His mother wasn’t supportive at first, he told the klatch, but she listened to her nephew’s explanation and came around. “Who could judge someone for the choices they make in that situation?”

“There’s a waiting list for kidneys of two to eight years,” Mays said. “Let’s say [in] four or five years, there was a kidney available. Your body can reject it … and then you’re back to the drawing board…. I told Precious about this like a year and a half ago … and she said, ‘I have to hang up now because I have to process this.’ And the next time I talked with her, she said, ‘I get it.’ ”

Mays said he doesn’t want to be “a prisoner to a process, like a machine or something.”

“And you have to do this indefinitely. It’s not like you’re on it for two or three years…,” he said. “It is. The. Rest. Of. Your. Life.”

“I’ve seen people that were on dialysis,” said Bradley, a former musician. “I think I’d rather be just, if I gotta go, I gotta go.”

Morgan said his father, who died last year, had kidney problems in the end and resisted extreme measures to extend his life.

“It’s not like he was at all suicidal, just like David’s not,” Morgan said. “The thing about David is, he’s always been so resolute about it. We’ve never had a discussion where I felt like we could waver him, or like he was on the fence.”

When he first resisted dialysis, Mays said, doctors set him up in a room with a video that explained the process.

“I watched the whole thing, and that was the clincher,” Mays said. “By the time I got through looking at that, I’m just going, ‘Oh HELL no.’”

It’s not that he wants to die, Mays said. It’s that he wants to live on his terms.

“The irony of the whole thing is, it’s all the people that I have around me — they’re the reason I’m willing to go like this. What I get from them in the way of being … uplifted and loved, well, when you have all that, you can deal with anything.”

He has his klatch buddies, he has Precious, he has his daughter in his life again.

“With people around that give a damn about you, care about you, you can deal … with death, you can deal with dying…. And I told my doctors I would rather live a shorter period of time, but with what I feel to be some decent quality of life, than live a longer period of time and be miserable. And I would be miserable on dialysis,” Mays said.

“Plus, I’m 70. It ain’t like I’m 30 and there’s so much life to live. I am the age that I am, and I would like to go further, sure, but it has to close out soon. And I’m fine with that, because I have lived.”

steve.lopez@latimes.com

Science

NIH budget cuts threaten the future of biomedical research — and the young scientists behind it

Over the last several months, a deep sense of unease has settled over laboratories across the United States. Researchers at every stage — from graduate students to senior faculty — have been forced to shelve experiments, rework career plans, and quietly warn each other not to count on long-term funding. Some are even considering leaving the country altogether.

This growing anxiety stems from an abrupt shift in how research is funded — and who, if anyone, will receive support moving forward. As grants are being frozen or rescinded with little warning and layoffs begin to ripple through institutions, scientists have been left to confront a troubling question: Is it still possible to build a future in U.S. science?

On May 2, the White House released its Fiscal Year 2026 Discretionary Budget Request, proposing a nearly $18-billion cut from the National Institutes of Health. This cut, which represents approximately 40% of the NIH’s 2025 budget, is set to take effect on Oct. 1 if adopted by Congress.

“This proposal will have long-term and short-term consequences,” said Stephen Jameson, president of the American Assn. of Immunologists. “Many ongoing research projects will have to stop, clinical trials will have to be halted, and there’ll be the knock-on effects on the trainees who are the next generation of leaders in biomedical research. So I think there’s going to be varied and potentially catastrophic effects, especially on the next generation of our researchers, which in turn will lead to a loss of the status of the U.S. as a leader in biomedical research.“

In the request, the administration justified the move as part of its broader commitment to “restoring accountability, public trust, and transparency at the NIH.” It accused the NIH of engaging in “wasteful spending” and “risky research,” releasing “misleading information,” and promoting “dangerous ideologies that undermine public health.”

National Institutes of Health.

(NIH.gov)

To track the scope of NIH funding cuts, a group of scientists and data analysts launched Grant Watch, an independent project that monitors grant cancellations at the NIH and the National Science Foundation. This database compiles information from public government records, official databases, and direct submissions from affected researchers, grant administrators, and program directors.

As of July 3, Grant Watch reports 4,473 affected NIH grants, totaling more than $10.1 billion in lost or at-risk funding. These include research and training grants, fellowships, infrastructure support, and career development awards — and affect large and small institutions across the country. Research grants were the most heavily affected, accounting for 2,834 of the listed grants, followed by fellowships (473), career development awards (374) and training grants (289).

The NIH plays a foundational role in U.S. research. Its grants support the work of more than 300,000 scientists, technicians and research personnel, across some 2,500 institutions and comprising the vast majority of the nation’s biomedical research workforce. As an example, one study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, found that funding from the NIH contributed to research associated with every one of the 210 new drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration between 2010 and 2016.

Jameson emphasized that these kinds of breakthroughs are made possible only by long-term federal investment in fundamental research. “It’s not just scientists sitting in ivory towers,” he said. “There are enough occasions where [basic research] produces something new and actionable — drugs that will save lives.”

That investment pays off in other ways too. In a 2025 analysis, United for Medical Research, a nonprofit coalition of academic research institutions, patient groups and members of the life sciences industry, found that every dollar the NIH spends generates $2.56 in economic activity.

A ‘brain drain’ on the horizon

Support from the NIH underpins not only research, but also the training pipeline for scientists, physicians and entrepreneurs — the workforce that fuels U.S. leadership in medicine, biotechnology and global health innovation. But continued American preeminence is not a given. Other countries are rapidly expanding their investments in science and research-intensive industries.

If current trends continue, the U.S. risks undergoing a severe “brain drain.” In a March survey conducted by Nature, 75% of U.S. scientists said they were considering looking for jobs abroad, most commonly in Europe and Canada.

This exodus would shrink domestic lab rosters, and could erode the collaborative power and downstream innovation that typically follows discovery. “It’s wonderful that scientists share everything as new discoveries come out,” Jameson said. “But, you tend to work with the people who are nearby. So if there’s a major discovery in another country, they will work with their pharmaceutical companies to develop it, not ours.”

At UCLA, Dr. Antoni Ribas has already started to see the ripple effects. “One of my senior scientists was on the job market,” Ribas said. “She had a couple of offers before the election, and those offers were higher than anything that she’s seen since. What’s being offered to people looking to start their own laboratories and independent research careers is going down — fast.”

In addition, Ribas, who directs the Tumor Immunology Program at the Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center, says that academia and industry are now closing their door to young talent. “The cuts in academia will lead to less positions being offered,” Ribas explained. “Institutions are becoming more reluctant to attract new faculty and provide startup packages.” At the same time, he said, the biotech industry is also struggling. “Even companies that were doing well are facing difficulties raising enough money to keep going, so we’re losing even more potential positions for researchers that are finishing their training.”

This comes at a particularly bitter moment. Scientific capabilities are soaring, with new tools allowing researchers to examine single cells in precise detail, probe every gene in the genome, and even trace diseases at the molecular level. “It’s a pity,” Ribas said, “Because we have made demonstrable progress in treating cancer and other diseases. But now we’re seeing this artificial attack being imposed on the whole enterprise.”

Without federal support, he warns, the system begins to collapse. “It’s as if you have a football team, but then you don’t have a football field. We have the people and the ideas, but without the infrastructure — the labs, the funding, the institutional support — we can’t do the research.”

For graduate students and postdoctoral fellows in particular, funding uncertainty has placed them in a precarious position.

“I think everyone is in this constant state of uncertainty,” said Julia Falo, a postdoctoral fellow at UC Berkeley and recording secretary of UAW 4811, the union for workers at the University of California. “We don’t know if our own grants are going to be funded, if our supervisor’s grants are going to be funded, or even if there will be faculty jobs in the next two years.”

She described colleagues who have had funding delayed or withdrawn without warning, sometimes for containing flagged words like “diverse” or “trans-” or even for having any international component.

The stakes are especially high for researchers on visas. As Falo points out for those researchers, “If the grant that is funding your work doesn’t exist anymore, you can be issued a layoff. Depending on your visa, you may have only a few months to find a new job — or leave the country.”

A graduate student at a California university, who requested anonymity due to the potential impact on their own position — which is funded by an NIH grant— echoed those concerns. “I think we’re all a little on edge. We’re all nervous,” they said. “We have to make sure that we’re planning only a year in advance, just so that we can be sure that we’re confident of where that funding is going to come from. In case it all of a sudden gets cut.”

The student said their decision to pursue research was rooted in a desire to study rare diseases often overlooked by industry. After transitioning from a more clinical setting, they were drawn to academia for its ability to fund smaller, higher-impact projects — the kind that might never turn a profit but could still change lives. They hope to one day become a principal investigator, or PI, and lead their own research lab.

Now, that path feels increasingly uncertain. “If things continue the way that they have been,” they said. “I’m concerned about getting or continuing to get NIH funding, especially as a new PI.”

Still, they are staying committed to academic research. “If we all shy off and back down, the people who want this defunded win.”

Rallying behind science

Already, researchers, universities and advocacy groups have been pushing back against the proposed budget cut.

On campuses across the country, students and researchers have organized rallies, marches and letter-writing campaigns to defend federal research funding. “Stand Up for Science” protests have occurred nationwide, and unions like UAW 4811 have mobilized across the UC system to pressure lawmakers and demand support for at-risk researchers. Their efforts have helped prevent additional state-level cuts in California: in June, the Legislature rejected Gov. Gavin Newsom’s proposed $129.7-million reduction to the UC budget.

Earlier this year, a coalition of public health groups, researchers and unions — led by the American Public Health Assn. — sued the NIH and Department of Health and Human Services over the termination of more than a thousand grants. On June 16, U.S. District Judge William Young ruled in their favor, ordering the NIH to reinstate over 900 canceled grants and calling the terminations unlawful and discriminatory. Although the ruling applies only to grants named in the lawsuit, it marks the first major legal setback to the administration’s research funding rollback.

Though much of the current spotlight (including that lawsuit) has focused on biomedical science, the proposed NIH cuts threaten research far beyond immunology or cancer. Fields ranging from mental health to environmental science stand to lose crucial support. And although some grants may be in the process of reinstatement, the damage already done — paused projects, lost jobs and upended career paths — can’t simply be undone with next year’s budget.

And yet, amid the fear and frustration, there’s still resolve. “I’m floored by the fact that the trainees are still devoted,” Jameson said. “They still come in and work hard. They’re still hopeful about the future.”

Science

Should bioplastics be counted as compost? Debate pits farmers against manufacturers

Greg Pryor began composting yard and food waste for San Francisco in 1996, and today he oversees nine industrial-sized composting sites in California and Oregon that turn discarded banana peels, coffee grounds, chicken bones and more into a dark, nutrient-rich soil that farmers covet for their fields and crops.

His company, Recology, processes organic waste from cities and municipalities across the Bay Area, Central Valley, Northern California, Oregon and Washington — part of a growing movement to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by minimizing food waste in landfills.

But, said Pryor, if bioplastic and compostable food packaging manufacturers’ get their way, the whole system could collapse.

At issue is a 2021 California law, known as Assembly Bill 1201, which requires that products labeled “compostable” must actually break down into compost, not contaminate soil or crops with toxic chemicals, and be readily identifiable to both consumers and solid waste facilities.

The law also stipulates that products carrying a “compostable” label must meet the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Organic Program requirements, which only allow for plant and animal material in compost feedstock, and bar all synthetic substances and materials — plastics, bioplastics and most packaging materials — except for newspaper or other recycled paper without glossy or colored ink.

Close-up of text on plastic cup reading Made From Corn, referring to plant derived bioplastics.

(Getty Images)

The USDA is reviewing those requirements at the request of a compostable plastics and packaging industry trade group. Its ruling, expected this fall, could open the door for materials such as bioplastic cups, coffee pods and compostable plastic bags to be admitted into the organic compost waste stream.

Amid pressure from the industry, the California Department of Resources Recycling and Recovery said it will await implementing its own rules on AB 1201 — originally set for Jan. 1, 2026 — until June 30, 2027, to incorporate the USDA guidelines, should there be a change.

Pryor is concerned that a USDA ruling to allow certain plastic to be considered compost will contaminate his product, make it unsaleable to farmers, and undermine the purpose of composting — which is to improve soil and crop health.

Plastics, microplastics and toxic chemicals can hurt and kill the microorganisms that make his compost healthy and valued. Research also shows these materials, chemicals and products can threaten the health of crops grown in them.

And while research on new generation plastics made from plant and other organic fibers have more mixed findings — suggesting some fibers, in some circumstances, may not be harmful — Pryor said the farmers who buy his compost don’t want any of it. They’ve told him they won’t buy it if he accepts it in his feedstock.

“If you ask farmers, hey, do you mind plastic in your compost? Every one of them will say no. Nobody wants it,” he said.

However, for manufacturers of next-generation, “compostable” food packaging products — such as bioplastic bags, cups and takeout containers made from corn, kelp or sugarcane fibers — those federal requirements present an existential threat to their industry.

That’s because California is moving toward a new waste management regime which, by 2032, will require all single-use plastic packaging products sold in the state to be either recyclable or compostable.

A worker at Recology’s Blossom Valley composting site rides his bike back to the sorting machines after a break in Vernalis, Calif., on June 26.

(Susanne Rust / Los Angeles Times)

If the products these companies have designed and manufactured for the sole purpose of being incorporated in the compost waste stream are excluded, they will be shut out of the huge California market.

They say their products are biodegradable, contain minimal amounts of toxic chemicals and metals, and provide an alternative to the conventional plastics used to make chip bags, coffee pods and frozen food trays — and wind up in landfills, rivers and oceans.

“As we move forward, not only are you capturing all this material … such as coffee grounds, but there isn’t really another packaging solution in terms of finding an end of life,” for these products, said Alex Truelove, senior policy manager for the Biodegradable Product Institute, a trade organization for compostable packaging producers.

(Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times)

Material is loaded into a mixing truck where biosolids and amendments are combined then stored in climate controlled piles to cure at the Tulare Lake Compost plant. (Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times)

“Even if you could recycle those little cups, which it seems like no one is willing to do … it still requires someone to separate out and peel off the foil top and dump out the grounds. Imagine if you could just have a really thin covering or really thin packaging, and then you could just put it all in” the compost he said. “How much more likely would it be for people to participate?”

Truelove and Rhodes Yepsen, the executive director of the bioplastic institute, also point to compost bin and can liners, noting that many people won’t participate in separating out their food waste if they can’t put it in a bag — the “yuck” factor. If you create a compostable bag, they say, more people will buy into the program.

The institute — whose board members include or have included representatives from the chemical giant BASF Corp., polystyrene manufacturer Dart Container, Eastman Chemical Co. and PepsiCo — is lobbying the federal and state government to get its products into the compost stream.

Greg Pryor, Recology’s director of landfill and organics, stands in front of a pile of processed compost at the integrated waste management’s Blossom Valley compost site in Vernalis, Calif., on June 26.

(Susanne Rust / Los Angeles Times)

The institute also works as a certifying body, testing, validating and then certifying compostable packaging for composting facilities across the U.S. and Canada.

In 2023, it petitioned the USDA to reconsider its exclusion of certain synthetic products, calling the current requirements outdated and “one of the biggest stumbling blocks” to efforts in states, such as California, that are trying to create a circular economy, in which products are designed and manufactured to be reused, recycled or composted.

In response, the federal agency contracted the nonprofit Organics Material Review Institute to compile a report evaluating the research that’s been conducted on these products’ safety and compostability.

The institute’s report, released in April, highlighted a variety of concerns including the products’ ability to fully biodegrade — potentially leaving microplastics in the soil — as well as their tendency to introduce forever chemicals, such as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), and other toxic chemicals into the soil.

“Roughly half of all bioplastics produced are non-biodegradable,” the authors wrote. “To compensate for limitations inherent to bioplastic materials, such as brittleness and low gas barrier properties, bioplastics can contain additives such as synthetic polymers, fillers, and plasticizers. The specific types, amounts, and hazards of these chemicals in bioplastics are rarely disclosed.”

The report also notes that while some products may break down relatively efficiently in industrial composting facilities, when left out in the environment, they may not break down at all. What’s more, converting to biodegradable plastics entirely could result in an increase in biodegradable waste in landfills — and with it emissions of methane, a powerful greenhouse gas, the authors wrote.

Yepsen and Truelove say their organization won’t certify any products in which PFAS — a chemical often used to line cups and paper to keep out moisture — was intentionally added, or which is found in levels above a certain threshold. And they require 90% biodegradation of the products they certify.

Judith Enck, a former regional Environmental Protection Agency director, and the founder of Beyond Plastics, an anti-plastic waste environmental group based in Bennington, Vt., said the inclusion of compost as an end-life option for packaging in California’s new waste management regime was a mistake.

“What it did was to turn composting into a waste disposal strategy, not a soil health strategy,” she said. “The whole point of composting is to improve soil health. But I think what’s really driving this debate right now is consumer brand companies who just want the cheapest option to keep producing single-use packaging. And the chemical companies, because they want to keep selling chemicals for packaging and a lot of so-called biodegradable or compostable packaging contains those chemicals.”

Bob Shaffer, an agronomist and coffee farmer in Hawaii, said he’s been watching these products for years, and won’t put any of those materials in his compost.

“Farmers are growing our food, and we’re depending on them. And the soils they grow our crops in need care,” he said. “I’ll grow food for you, and I’ll grow gorgeous food for you, but give us back the food stuff you’re not using or eating, so we can compost it, return it to the soil, and make a beautiful crop for you. But be mindful of what you give back to us. We can’t grow you beautiful food from plastic and toxic chemicals.”

Recology’s Pryor said the food waste his company receives has increasingly become polluted with plastic.

He pointed toward a pile of food waste at his company’s composting site in the San Joaquin Valley town of Vernalis. The pile looked less like a heap of rotting and decaying food than a dirty mound of plastic bags, disposable coffee cups, empty, greasy chip bags and takeout boxes.

“I’ve been doing this for more than three decades, and I can tell you the food we process hasn’t changed over that time,” he said. “Neither have the leaves, brush and yard clippings we bring in. The only thing that’s changed? Plastics and biodegradable plastics.”

He said if the USDA and CalRecycle open the doors for these next-generation materials, the problem is just going to get worse.

“People are already confused about what they can and can’t put in,” he said. “Opening the door for this stuff is jut going to open the floodgates. For all kinds of materials. It’s a shame.”

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoSchumer to force Senate reading of Trump's entire 'big, beautiful bill'

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoNew L.A. Trader Joe's opens across the street from … another Trader Joe's

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week ago5.4 million patient records exposed in healthcare data breach

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump administration takes on new battle shutting down initial Iran strike assessments

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoTesla says it delivered its first car autonomously from factory to customer

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoUganda’s President Museveni confirms bid to extend nearly 40-year rule

-

News1 week ago

Live updates: Republicans race to meet Trump’s July 4 deadline for agenda bill | CNN Politics

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoSee How Trump’s Big Bill Could Affect Your Taxes, Health Care and Other Finances