The first time Lydia Bulas chased a private jet down the runway at Florida’s Lauderdale-Hollywood Airport, it was May of 1983 and America was losing the war on drugs. She was a 31-year-old rookie special agent, slouched in a surveillance car and watching a Cuban load 17 cardboard boxes on to a Learjet. The balding man staggered up the stairs as the twin engines started to whine. She eyed her radio, willing it to crackle to life, but it didn’t comply. The aircraft lurched forward and made for the runway. Finally, Bulas got the call from customs — whatever the man was transporting, he hadn’t signed a form. She roared on to the runway in hot pursuit.

A legion of cop cars joined the drag race, but the jet was picking up speed. Bulas was neck and neck with the cockpit and running out of runway. She swung in front of the aircraft, forcing the pilot to screech to a halt. Revolver drawn, she leapt out into the heat. Agents with shotguns stormed the cabin and tore open the boxes. Inside, they found more than $5mn in cash — exactly what Bulas was looking for. Cartels were importing a then — new drug, cocaine, by plane and boat, but their challenge was sending their profits in cash back to Colombia.

A government audit of the US banking system’s cash flow had recently discovered more than $6bn in unexplained banknotes flowing from banks in South Florida — more than the entire US currency surplus and theoretically enough to sink the actual American economy. So the government dispatched undercover operatives to stop it. But Bulas wasn’t with the DEA or FBI. She worked for the IRS, on a secret operation that had nothing to do with tax refunds. Her boss had issued his staff with novelty business cards that stated their line of work:

OPERATION GREENBACK.

USED CARS, WHISKEY, PEAT MOSS, NAILS, LAND, FLY SWATTERS, RACING FORMS, BONGO DRUMS. WARS FOUGHT, GOVERNMENTS RUN, BRIDGES DESTROYED, UPRISINGS QUELLED, REVOLUTIONS STARTED. TIGERS TAMED, SALOONS EMPTIED, ORGIES ORGANIZED, VIRGINS CONVERTED, COMPUTERS VERIFIED

The Cuban in the Learjet turned out to be Ramon Milian-Rodriguez, a 32-year-old businessman with a masters degree and an arrogance that stunned investigators. “I’m a launderer of narco-dollars for the Who’s Who of drug dealers,” he boasted to federal agents after his arrest. “Nothing else generates this kind of cash. Not even General Motors.” He told them they, “didn’t know what they had here”.

Milian-Rodriguez was right. American law enforcement had mistaken the narcotics industry for disparate groups of “cocaine cowboys” but in Colombia, Pablo Escobar was building a violent drug empire that stretched from Medellín to Miami. When Bulas’s colleagues searched Milian-Rodriguez’s office, they found a briefcase stuffed with records that showed he had laundered a staggering $146mn in the previous eight months alone. They picked the lock on his closet and discovered a submachine gun in a sack, helpfully labelled “UZI”. They unzipped another bag and found 28kg of cocaine.

Bulas, who is Cuban-American, couldn’t contain her emotions. “I was very upset that a Cuban would do that,” she recalls. “You come here to this country, they give you a chance to prosper, and you go and do illegal stuff. No. Go back to where you came from.”

When Lydia Bulas was eight years old, her father arrived at their apartment in Havana, Cuba, and started stuffing cash into suitcases. It was 1960, and Fidel Castro’s goons had just informed her grandmother that the family farm now belonged to the government. “My dad was a doctor. He studied medicine while Castro was studying law in the University of Havana, so he knew the guy was no good,” she recalls. He said, “We gotta get out of here.” Bulas was spirited out of the country on an aircraft with her mother, grandmother and brother. Like so many Cuban émigrés, she arrived in Miami hoping for a new life.

But being new wasn’t easy, especially for a bookish kid with glasses. “I was kind of shy, sort of a nerd,” Bulas says. “I went to a Catholic school, and I spoke no English. The teacher happened to be a Cuban lady. She stayed after school with me and taught me. Until I got it right, I never left my desk.” By the time she graduated high school, she was fluent in English, a straight-A student and headed to the University of Miami to study accounting. At night, her mother begged her to go to parties, but she preferred to stay home and study the tax code. In 1975, she took an entry-level job at the IRS answering tax-payers’ questions.

Even for a wallflower, cubicle life was dull. “I’m a Gemini, so I’m always a very active person,” Bulas says. A marriage to a cousin’s friend after college lasted only three years. “I fell out of love with him,” she explains. She eventually tried nightclubs, such as The Mutiny in Coconut Grove, a waterfront drinking hole that came to be known as “Hotel Scarface”, where bartenders were selling more bottles of Dom Pérignon than in any other establishment in the world at the time. She was shocked to see people openly snorting white powder. “My father, when I was little, he once took me to a hospital where all the drug addicts were,” she recalls. “It shocked me so bad that today I can say that I have never even smoked a joint.”

By then, drugs had changed Magic City. Bulas watched TV news reports about Wild West-style shoot-outs between rival Colombian drug traffickers in shopping malls. Bullet-riddled bodies were turning up in trunks. “After I started working for the government, I woke up,” Bulas says. While local law enforcement and the DEA struggled to contain the tonnes of cocaine arriving at the border, the IRS became concerned with the spectacular amounts of cash it generated.

One day, a Cuban colleague at the IRS boasted to Bulas about his new job running raids for the “criminal division”. He said they urgently needed Spanish speakers and people who understood numbers. Bulas hoped it might be good for her social life. “You didn’t want to say you worked for the IRS,” she recalls, explaining that people feared she would audit them. “Afterwards I could say, ‘I don’t do taxes, I do criminal division.’”

At a federal training centre in Georgia, Bulas learnt to fire a revolver. She learnt to poke an assailant in both eyes, stamp on his toe, then “kick him in the balls”, she recalls. Instead of a skirt, she wore jeans and a gun on her hip. The glasses were gone. “I felt like it really pulled my ego very high,” she admits. It also gave her life meaning. As only the second woman to join the division, she was eager to make her mark.

In 1980, Bulas was assigned to Operation Greenback, named for the green paper money issued by the Union government during the civil war. The team comprised maths whizzes from the IRS, the US customs service and Justice Department. Being the first Latin woman on the task force gave her an additional responsibility. “I was very, very grateful to this country,” she says, “for having allowed me to become what I was.”

Mike McDonald, the agent in charge of Operation Greenback, wore a sensible, side-parted hairstyle and kept a huge dictionary on his desk. He also liked to pose for photos with a semi-automatic rifle and had a wicked sense of humour. “He was a brain. The most knowledgeable guy regarding money laundering that you could ever meet,” Bulas says. “I looked up to him. He wasn’t like a boss. He was like one of us.”

Operation Greenback quickly outgrew its headquarters at the federal building in downtown Miami and moved into a location recently abandoned by a defunct Miami newspaper. Agents had to steal furniture from their neighbour, the US attorney’s office, in a heist that caused a bureaucratic conflict. Their new headquarters had a pirate-ship vibe. Boxes overflowed with evidence; electric typewriters clattered; people smoked at their desks, if only to mask the smell of rotting food and diapers leaking from bags of garbage taken from traffickers’ homes and awaiting analysis. “It was disgusting sometimes,” Bulas recalls.

“We were just all kids,” recalls Larry Sands, a special agent with Operation Greenback, who colleagues liked to call “Catfish”. “We were young, we were dedicated to the mission.” According to Jonathan Rosen, an assistant professor and organised crime expert at New Jersey City University, Greenback didn’t need guys with guns to beat the traffickers, but “accountants and an army of nerds”. Brave nerds willing to go face to face with international criminals. “Back then, since I was young, I thought I was invincible,” Bulas says.

Bulas spent the early 1980s watching small Miami banks that cops and criminals called Coin-O-Washers. She studied suspicious customers, who pushed in cart loads of cash with a deposit slip gripped between their teeth. Others carried banknotes that reeked of fish, having sat in bags used by seafaring smugglers. Back then, there were no money laundering laws. Banks were required to file a report when someone deposited $10,000 or more, but few bothered to.

One day, Bulas watched a portly Colombian travel agent arrive at the Great American Bank of Dade County, a known Coin-O-Washer. Greenback agents suspected the man, 46-year-old Isaac Kattan, was a major money launderer. But Kattan didn’t strike Bulas as a drug guy. The softly spoken father-of-two drove an old Chevrolet Citation and carried a mysterious purple satchel. She soon learnt that each of his four rented apartments contained a high-speed money counter. Every day she watched him drive trunk-loads of cash to the bank at recklessly high speeds, depositing up to $4mn a day, between meetings at phone booths and parking lots. One DEA agent on his tail often wondered: “Doesn’t this guy ever stop?”

Tellers at the bank also worked nonstop, counting Kattan’s millions through the night. Though technically he was doing nothing illegal, his behaviour set alarm bells ringing. One morning in 1981, Bulas watched a car thief drive off in Kattan’s car, leaving him stranded outside the bank. (Miami was, by then, the crime capital of the world.) “What the hell?” she said to herself, as Kattan begged bank employees: “No police! No police!”

Bulas and 20 Greenback agents raided the bank. They arrested three employees who were in cahoots with Kattan and seized boxes of documents that revealed the scope of his operation. Every dollar Kattan deposited was turned into a credit for pesos and cashed out in Colombia, leaving a tidy profit for the bank. “We were able to build a case against him,” she says. They could prove he was involved in drugs, but didn’t know how to prosecute him. Then, a stroke of luck.

In February 1981, six undercover DEA and IRS agents followed Kattan all day. They watched him order a Cuban coffee, before he met two men in a flashy Jaguar and handed them a mysterious red briefcase. Agents were ordered to tail the car and “take ’em”. Inside Kattan’s suitcase, they found 20kg of cocaine with a street value of more than $300,000. After they slapped on the handcuffs, agents found $16,000 in cash under his front seat and $385,000 in cashiers’ checks in his briefcase. Inside his purple satchel? Evidence of hundreds of millions of dollars in money laundering transactions. Bulas recalls seeing Kattan’s face staring out from the front page of the Miami Herald, under the headline: SOUTH FLORIDA’S AL CAPONE.

“He was a dead duck,” says Charles Blau, who prosecuted the case. Blau, a Midwesterner from Indiana, knew they’d got lucky. “It was fortuitous, I guess, on our part that the one time that he made a dumb mistake and got in the middle of a drug transaction, we were watching him do it.”

It took just 20 minutes for a jury to convict Kattan of drug conspiracy. On August 17 1981, he was sent to prison for 30 years. The Great American Bank of Dade County became only the second ever US bank indicted for money laundering. One employee was caught in a sting operation that foiled a plot to blow up prosecutors and was sent to prison. Blau, the prosecutor, recalls terrifying a first date by holding a mirror beneath his car, checking for bombs. “I don’t think she went out with me [again] for six months,” Blau recalls. (They’re still married.)

Kattan was just the start. In the first few years of the 1980s, Operation Greenback smashed a total of seven money laundering rings involving 16 narcotics organisations that were responsible for $2bn in trafficked cash. The operation boasted 164 arrests, 211 indictments, 63 convictions and $38.5mn in seized currency. Those days whizzed by like dollar bills rattling through a counting machine, and the team who worked in the former newspaper office were now creating their own headlines. “Heck, we wrote the mission, with accomplishments every day,” recalls Catfish.

Bulas was finally enjoying her social life, but work often got in the way. One night she was dining with a girlfriend in Coral Gables when she overheard two men talking loudly in Spanish about “merchandise”. “If these people pay with a credit card, we’re going to follow them,” Bulas whispered. When their main course arrived, they had already left. By then, Bulas had tailed the suspects to a warehouse, which she later discovered was full of drug cash.

Another time, an informant tipped off Bulas to some cash hidden at a Colombian safe house, behind a fake wall. During the raid, Bulas knew the location of the cash, but needed to protect her source. So she told the suspects that her sniffer dog barked when he found banknotes. “I kicked the dog in the ass,” she recalls, adding that it was a gentle kick. When she pulled out the cash, one of the suspects lamented: “Shit, that dog is really good.”

The jaw-dropping stings continued. When Bulas stopped the Learjet on the tarmac in May of 1983, it was the biggest cash seizure in US history and a huge splash for Operation Greenback. Even the suspect, Milian-Rodriguez, recalled the bust fondly. “My arrest was a Hollywood arrest, you can see this in any action movie,” he later said. “The anti-hero gets on his private jet . . . and, all of a sudden, 100 police cars chase you down the runway.” Milian-Rodriguez was later sentenced to 43 years in prison for money laundering.

Yet the jailing of Kattan turned out to be a false victory for Bulas and Operation Greenback. Banks in south Florida were no longer willing to take in truckloads of dirty cash. The party was over. “Miami lost its role as a critical area for money laundering. Our banking system suffered, so did the housing market,” says Bruce Bagley, a former University of Miami professor and expert on money laundering (who, incredibly, was jailed in 2020 for money laundering). Milian-Rodriguez admitted that the $5.4mn on board his Learjet was a “monthly stipend” headed to Panama’s General Manuel Noriega, who was now washing the cartel’s cash and making Operation Greenback harder than ever.

By 1984, Bulas was starting to feel the strain. She was 32 and a single mother, juggling undercover assignments while wrangling babysitters. An unhappy marriage to a Syrian waiter had lasted less than a year, and she had given up on dating. “You don’t want to bring any guy [home] just for the hell of it. If you have a daughter, you have to be careful,” she says. Becoming a mother had made the war on drugs personal. She couldn’t imagine seeing her daughter in rehab or worse. When she took risks at work, Bulas admits, “I did it mainly for her.”

Pablo Escobar and the Medellín Cartel controlled 80 per cent of the world’s cocaine trade at that time. Laundered cash made Escobar rich, and he was eventually added to Forbes’ first ever List of International Billionaires, alongside the owner of car giant Fiat and the Benetton fashion family. He wore a diamond-encrusted Rolex; he purchased a bullet-ridden 1930s touring car purportedly once owned by gangsters Bonnie and Clyde; he stocked his private zoo with a soccer-playing kangaroo and a pair of rare black parrots valued at $20,000 apiece. But his violent trade created misery and death on the streets of Colombia and Miami.

In 1984, at the height of the cocaine boom, McDonald sent Bulas on undercover missions posing as an intermediary. As “Lydia Barrera”, Bulas promised cartel members she could launder dirty cash through corrupt bankers without leaving a paper trail. Once they were on the hook, Greenback agents would launder some of the cash, then follow them back to their stash house, where uniformed agents would seize the money. They called it “ripping” the cash.

“You have to dress like you have money,” Bulas says. She wore fake jewellery and carried herself with extra swagger. After the sting and the big reveal, she led the negotiations too. “If you want to have your sentence reduced,” she told the suspects, “you introduce us to your big guy and tell them I’m very reliable.” It was effective but risky. One night in Puerto Rico, Bulas was partying with cartel members at a disco called Hunca Munca, wearing a blonde wig, when she ran into a friend from high school. She pulled the woman into the restroom and whispered: “You don’t know me!”

Support for Bulas arrived in 1984, when Greenback recruited more female operatives. Former IRS auditor Debbie Crumley, 32, transferred to the criminal division when her husband’s job took the couple to Miami. She arrived from a small-town in Georgia with blonde bangs and a “bless your heart” southern accent, behind the wheel of a burgundy Nissan convertible, blasting Tina Turner’s “What’s Love Got To Do With It”. “I just wanted to do something with some pizzazz,” she recalls. When she teamed up with Bulas, other agents started calling them “Cagney and Lacey” after the television cop duo.

Crumley’s undercover persona was a ruthless businesswoman who casually dealt in millions. “But you also had to be normal,” she explains. “You couldn’t come across as too anxious. You were just a person trying to make a deal and, fortunately, most of the people we did that with believed us.” On every sting, the female agents were told a secret code-word, like “Disneyland” or “daycare”, to summon armed agents if a deal went south. The cartel’s couriers, Bulas recalls, “were little shitheads”.

The bad guys were not stupid, Crumley says. “They figured out they were being followed sometimes, and then they turned the tables on us and started following us.” One time a suspect told her: “I know where you and your husband had dinner last weekend.” Bulas and Crumley were issued specially designed green leather handbags to carry their handguns, which came with speedloaders and hollow-point bullets with more stopping power.

Back in the office, they posed for goofy mugshots for McDonald, who posted them to a fictional IRS Ten Most Wanted List on the wall. In truth, they were the stars of the whole operation. “They were women out of the ordinary,” says Dick Gregorie, a prosecutor who worked on various Greenback cases. “They were every bit as tough as the guys were and they had no problems in standing up to them and making sure they got heard and things got done.” This put some noses out of joint.

Not long after she joined Greenback, Crumley was driving past a suspect’s house late at night. The road was lined by tall trees, and it was pitch black. She noticed a car drawing closer to her rear bumper. Certain that her cover was blown and armed Colombians were on her tail, she radioed Catfish for back-up. “I pulled out my weapon, and I was ready to do whatever I had to do,” she recalls. Agents rammed the car to a stop. “It was one of the agents from Greenback who was playing a trick on me. I remember Catfish saying, ‘You fool . . . she was ready to take you down.’”

Another night Crumley arrested two traffickers, a brother and sister, in possession of several kilos of cocaine. The woman had a six-year-old son, Enrique, who found himself at Greenback headquarters with Crumley. “Against his chest he cradled his mother’s empty purse which seemed to act as his security blanket,” she recalls. When his mother told him she was going to jail, tears streamed down the boy’s face. “She showed no emotion,” Crumley recalls. After she took Enrique to social services, his mother received an eight-year sentence, and never once asked about her son, she says.

In their bid to capture bigger targets, Bulas and Crumley set their sights on two Uruguayan launderers named Roberto del Pino and Carlos Sarmiento. They both looked to them like slick South American smugglers straight from Central Casting. Del Pino was the one with the limp. Both had recently turned 30 and had tired of working in a sausage factory and selling books, before finding success smuggling gold into Colombia in del Pino’s wooden leg. After a tarot reader introduced them to some Colombians, they started sending tonnes of cash in twenties, fives and one-dollar bills from Miami and Los Angeles back to Medellín.

The key to their operation was a striking Puerto Rican woman named Maria, who wore skyscraper heels and had the type of jet black mullet made popular by Cher. For a 2 per cent commission, Maria arranged to transfer their money undetected by US authorities, through what she called “a dirty banker”. In the space of a few days in January 1986, the Uruguayans slipped Maria nearly a million dollars in cash from the trunk of their car in a Pizza Hut parking lot. Maria was not her real name. She was Awilda Villafane, an undercover US Customs agent working with Bulas and Crumley, and Operation Greenback’s latest undercover operative. “We would tell her what to do,” Bulas explains.

Soon, del Pino and Sarmiento’s luck started to run out. They had $336,000 in cash and $465,000 in cashiers’ checks ripped from a safe during a raid in October 1985. Two days later, agents seized $1.2mn from the trunk of their Volkswagen Jetta. By then, “Maria” had laundered more than $17mn for the Uruguayans, while helping the government seize around $12mn. This earned Sarmiento an uncomfortable trip to Medellín to explain himself to Pablo Correa. Before Escobar had him murdered, the construction magnate was one of the cartel’s most ruthless drug traffickers. On his return to the US, Sarmiento warned Maria that if they lost any more money, the Colombians would “scrape us off the face of the earth”.

The raids continued, says Bulas.

“They were losing millions.”

In early February 1986, Villafane arrived at the Greenback headquarters with a cassette tape that made everyone sit up. A wiretap had recorded Sarmiento and del Pino complaining about their losses and fretting about Escobar sending someone from Medellín to see “what the hell was going on”. Luis Javier Castano-Ochoa (who is not related to the infamous Ochoa brothers, who co-founded the Medellín Cartel) was a lawyer and politician believed to be the cartel’s main financial adviser and frontman. “We were ecstatic because it was the first time we had someone who was really close to Escobar,” Bulas says. McDonald knew that capturing Castano-Ochoa would put a huge dent in the cartel’s operation. He decided to use “Maria” to lure him into a money-laundering sting. “I guess he trusted [her] very much,” Bulas recalls.

There was rain in the wind on February 7 1986, as Villafane, dressed as Maria, swung into a Burger King parking lot near the airport. Her Colombian connection leaned into her window and said, “The dopers want to meet us.” When the man slipped into the restaurant to buy a Coke, Villafane had a seven-minute window to talk to Bulas through a concealed microphone. Castano-Ochoa was coming, she said. They should scramble a team. “There were a lot of us outside,” Bulas recalls.

In her rear-view mirror, Villafane watched a red Buick Regal pull into the lot. Rain was now beating on the roof of Bulas’s car as she watched two smartly dressed men step out of the Buick. The balding man with closely cropped hair on the sides was Castano-Ochoa, the other was his driver. Villafane followed the men into the Burger King. Inside, Castano-Ochoa found a table away from the other customers. “I am going to take your car,” he told Villafane flatly. “You give me the keys and we are going to have the merchandise put into the trunk.” Villafane realised that if the men discovered the recording equipment whirring under her front seat, she could be killed.

“You can’t take my car because it is registered to me,” she said quickly, and suggested switching to a rental car waiting nearby. Castano-Ochoa pondered for a second, then agreed. Listening to their conversation in her car, Bulas breathed a sigh of relief.

Another of Castano-Ochoa’s men accompanied Villafane to a nearby grocery store to pick up the rental car. He transferred a suitcase and a box from his trunk into hers and drove away. When Villafane delivered the luggage to the Greenback office, agents found it stuffed with $828,000 in cash — enough to warrant an arrest. Six days later, agents surprised Castano-Ochoa at a Holiday Inn and arrested him. In his possession was a briefcase full of documents revealing a cocaine operation involving 2,957kg and approximately $56mn — one of the largest ever smuggling rings discovered on US soil.

Operation Greenback was now so successful that law enforcement agencies in 35 other US cities adopted its methods. “The best way to get [convictions] is through people ratting or squealing or informing,” explains Bagley, the money-laundering expert. Meanwhile, Isaac Kattan had spent hundreds of hours telling prosecutor Charles Blau exactly how the cartel laundered its cash. “He was probably one of the better teachers I’ve ever had,” Blau says. Those conversations, together with reports from Mike McDonald and Operation Greenback, formed the basis for the money laundering statutes passed into law by Congress in October 1986. Now that money laundering was a federal crime, the stage was set for Castano-Ochoa’s trial.

In May 1987, a court heard that Castano-Ochoa and the Medellín Cartel was responsible for the $6bn in unexplained cash flooding the US banking system. To illustrate his point, Prosecutor Gregorie showed the jury what $2.1mn in cash looked like. “We had to bring it up with the elevators and roll it into the courtroom,” he recalls. During the six-week trial, he introduced colourful witnesses, including the notorious drug trafficker and informant Max Mermelstein, who told the court that the papers found in Castano-Ochoa’s briefcase proved he “was in charge of the entire operation”.

“We had a lot of evidence, so he was toast,” Bulas recalls. She had also convinced the Uruguayans to testify, despite Castano-Ochoa allegedly warning one of them: “I am going to bring your son’s head on a platter.” Sarmiento and del Pino’s evidence helped to send Castano-Ochoa to prison for 16 years. (The smugglers were released for time served and deported.)

Bulas, Crumley, McDonald and the Greenback team celebrated at a local bar with prosecutors. “For me, it was a major trial. This was a major, major player,” says Gregorie. Putting it another way, Catfish says: “The worst thing that happened to Ochoa was Lydia Bulas.” After US Marshals led the Colombian away to a federal US prison, his lawyer quietly approached Bulas, she recalls. “He told me that if I ever decide to leave the IRS he would hire me as an investigator,” she says. (Castano-Ochoa is now free and still involved in politics in Colombia. He could not be reached for comment.)

Bulas continued working with Operation Greenback until it ended in 1993, shortly after Colombian special forces shot and killed Pablo Escobar on a Medellín rooftop as he tried to flee. The destruction of his money-laundering scheme, along with undercover missions at home and abroad, contributed to the spectacular downfall of the Medellín Cartel. Bulas remembers the jubilation in the office when the news of his death broke, but she was in no mood to celebrate. “I was relieved,” she recalls. Bulas retired in 2002, long after the good old days of Operation Greenback were over, she says. After the September 11 attacks in the US, the war on drugs became the war on terror, and she felt there was too much red tape and paperwork. “I said, ‘screw this,’” she recalls. She went to work for McDonald in the private sector, advising foreign banks on how to abide by American laws. It gave her more time to spend with her family.

Bulas is 71 now and lives in Miami with her 42-year-old daughter, her son-in-law and their two-year-old son. When she hangs out with Crumley, they still call each other by their last names, as if Operation Greenback never ended. She even keeps a photograph of Escobar drenched in his own blood, as a memento of her life’s work. Before he was killed, the drug lord spent his final months on the run. At one point, he found himself freezing to death with his nine-year-old daughter in the mountains above Medellín. He looked for something to burn to keep her warm and reached for some sacks filled with $2mn in American greenbacks. In desperation, he lit a match and — poof — up it went.

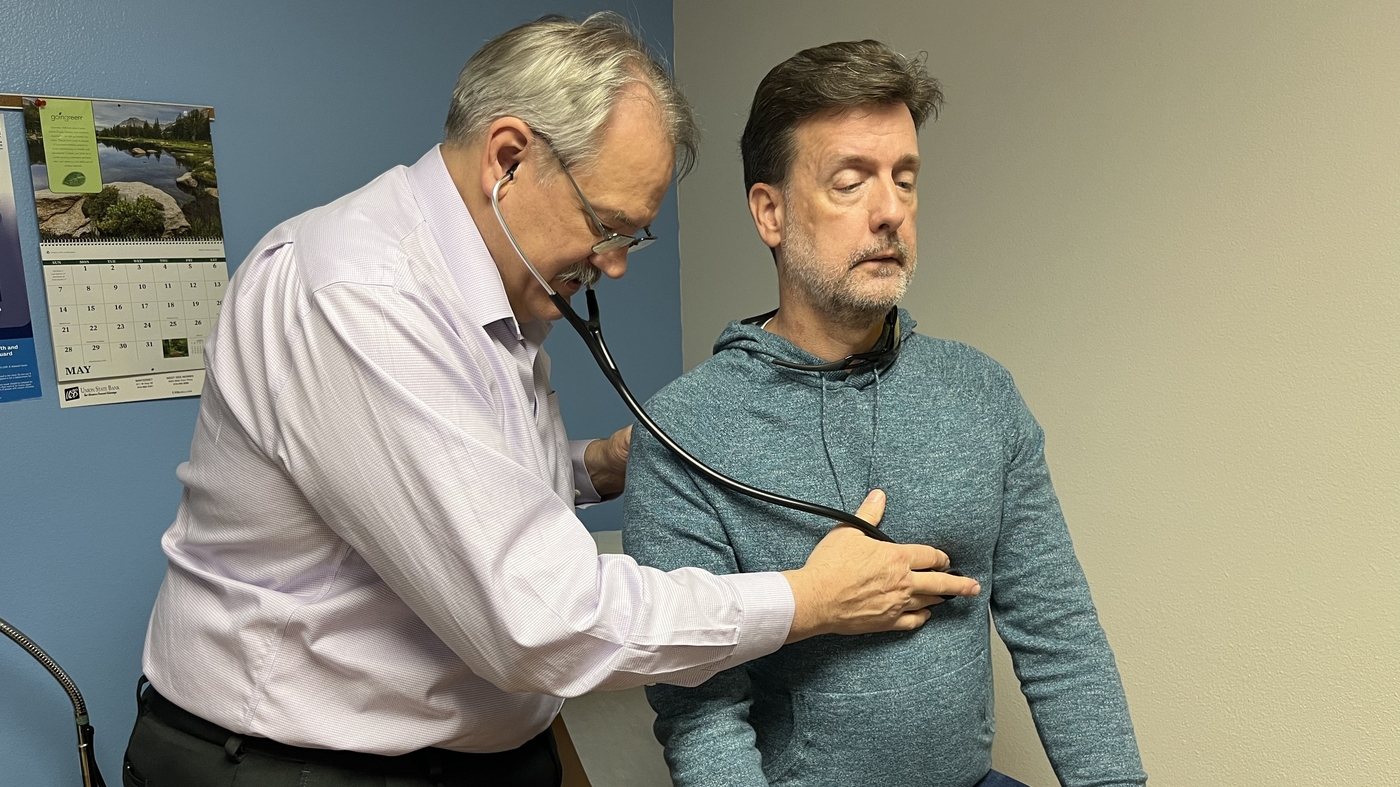

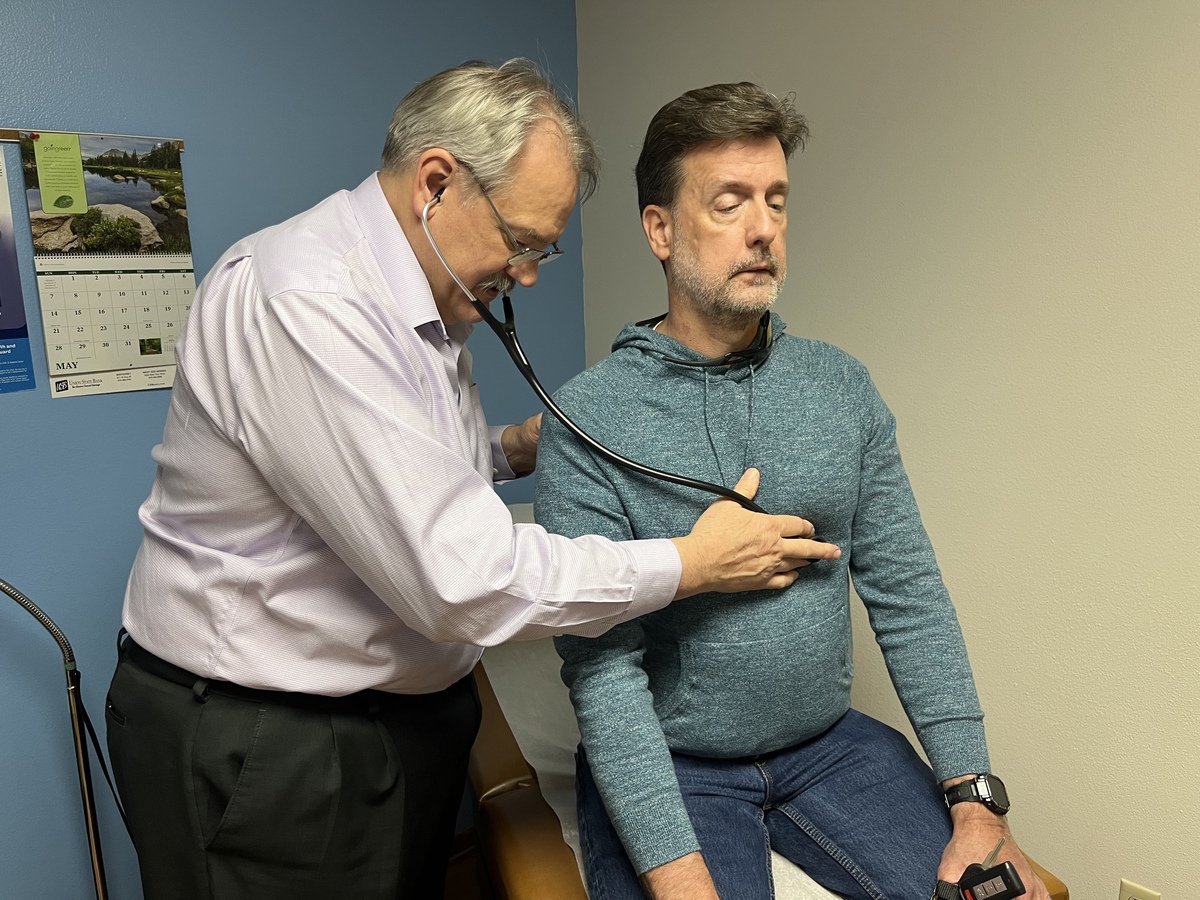

ABOUT THE PHOTOGRAPHY

Tania Franco Klein is a Mexico City-based photographer. For this article, FT Weekend Magazine invited Klein to create fictional scenes that reflect aspects of this article. These photographs do not contain individuals or locations featured in the story

Follow @FTMag to find out about our latest stories first and subscribe to our podcast Life and Art wherever you listen