South Dakota

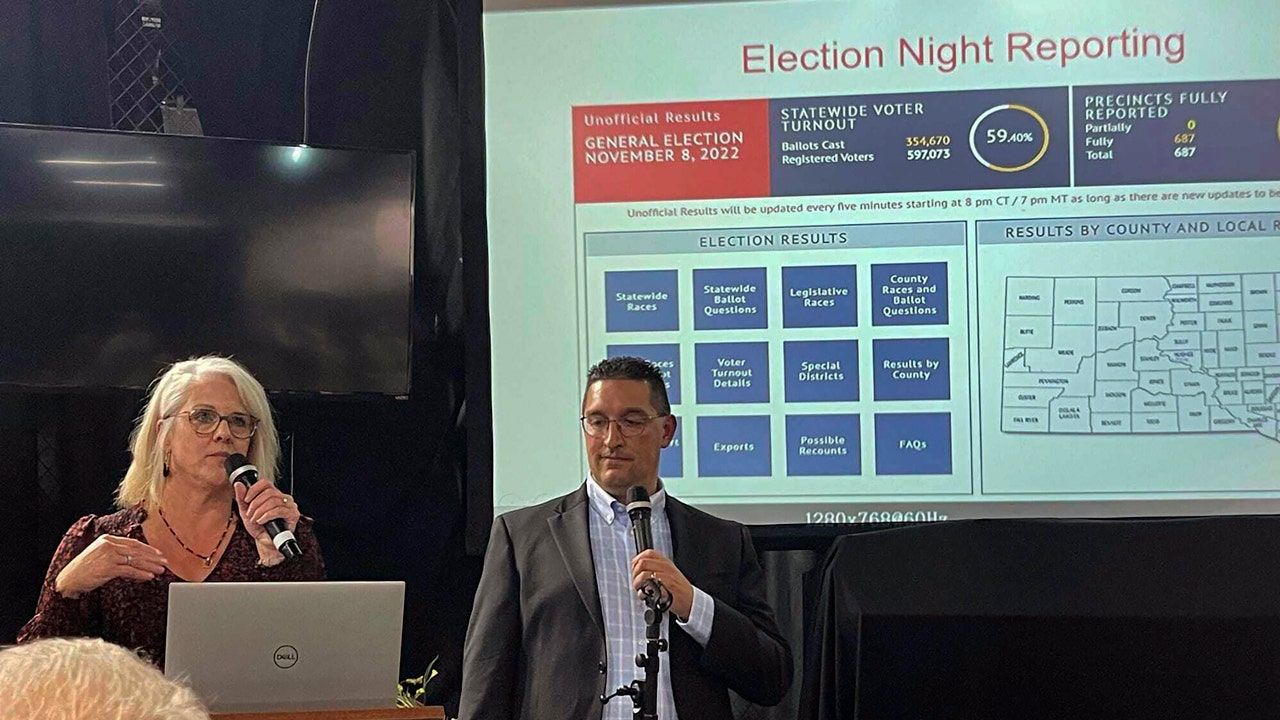

Marijuana vote count continues into the night

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/gray/QQDLNCNX5VFCHLOTBW4ZFL6P2I.bmp)

SIOUX FALLS, S.D. (Dakota Information Now) -Leisure marijuana legalization has been a scorching button matter in South Dakota because the election again in 2020 when 54% of voters stated sure to legalizing marijuana recreationally.

Each supporters and opponents remarking on the distinction on this election in comparison with 2020.

Rhonda Milstead is a volunteer for Shield South Dakota Youngsters and stated it was essential for the group to step up on this election.

“We took an actual hands-on method. In 2020 we anticipated frequent sense to rule the day however we realized it didn’t. We thought this was, it’s not South Dakota, marijuana isn’t South Dakota, we don’t want it, we don’t need it, it’s not pretty much as good for us, it’s not us,” stated Rhonda Milstead, Shield South Dakota Youngsters volunteer.

These in help of I-M-27 say they targeted on restoring what the individuals voted on again in 2020.

“A part of this marketing campaign is that we’re restoring the need of the individuals and plenty of the those that help our efforts consider simply as a lot within the poll initiative course of as they do in hashish reform,” stated Matthew Schweich, Sure on 27 marketing campaign supervisor.

Votes are nonetheless being counted right now.

For an replace on outcomes observe the hyperlink at Election Outcomes (dakotanewsnow.com)

Copyright 2022 KSFY. All rights reserved.

South Dakota

Is your farm vulnerable to cybersecurity attacks?

MADISON, S.D. — With precision agriculture technology becoming more and more advanced, how do farmers keep their equipment and records safe from cybersecurity breaches?

Students and researchers at Dakota State University in Madison, South Dakota, are able to climb in the tractor seat and conduct research surrounding cybersecurity in farm equipment in their on-campus tractor cybersecurity lab.

“The security aspect of things is just trying to make sure that all of our devices, whether they are smart tractors or any sort of even smart tablets or anything that farmers are using are secure and safe and aren’t leaking any information that they shouldn’t be,” said Austin O’Brien, associate professor of computer science and Master of Computer Science coordinator at Dakota State University.

Ariana Schumacher / Agweek

They are also looking at the impacts of artificial intelligence.

“We are working on different projects of how to use AI in various aspects, whether that’s gathering data so farmers can make better decisions, ranchers same thing, or they can also perhaps have higher yields, things of that nature and then autonomous self-driving tractors, things along those lines,” O’Brien said.

The goal of this research is to make sure our farm equipment is secure. They have joined forces with various industry partners including AI Sweden, South Dakota State University and Case IH New Holland.

“We want to make sure that really nefarious agents, you know, cyber hackers, attackers or whoever, they are not able to gather information from these devices,” O’Brien explained. “Also, so that they might not get in and then also take control of any of these or even put bad information inside of that.”

Ariana Schumacher / Agweek

The research set up is unique and makes students and researchers feel like they are actually on the farm.

“We have kind of the set up, I would say almost a little more for fun. We’ve got the driver’s seat and everything and so there is a simulator that is attached to it that is kind of like driving a tractor,” O’Brien said.

But the lab is for more than just fun.

“Maybe the more important part is the stuff that we don’t show,” O’Brien explained. “We are working with CNH and they have proprietary hardware, so we aren’t really allowed to show the actual hardware, but it is more of a smaller device that we have inside our labs so that way we have a good idea of what kind of hardware we are working with, where the inputs and the outputs are and what kind of power that it has.”

Those involved in the project are excited to be working on something that can make an impact on South Dakota’s largest industry: agriculture.

“Students really like the idea that we have been able to research and work on something that actually has a real impact on the South Dakota economy,” O’Brien said.

U.S. farmers and ranchers rapidly have been adopting technologies into their operations. The

2022 U.S. Census of Agriculture

said the percentage of farms with internet access continues to grow, now standing at about 79%. The 2022 Ag Census was the first to list precision agriculture adoption as a farm characteristic, and it estimated that less than 12% of farms were using the technologies. However, among the highest grossing farms — those that sell more than $1 million in farm products — precision ag technology use was at about 39%.

Adoption has been more swift in row crops. A February 2023 USDA study,

“Precision Agriculture in the Digital Era: Recent Adoption on U.S. Farms,”

said farmers were using auto-steer and guidance systems on more than 50% of U.S. acreage planted to corn, soybeans, winter wheat, cotton, rice and sorghum. That’s up from an estimated 10% in the early 2000s.

The use of precision agriculture technologies in row crops holds the possibility of reducing inputs and environmental footprint by more precise placement of seed and fertilizer and by more precise field coverage with less overlap thanks to guidance systems. Yield monitors can provide valuable information about field performance and resource allocation. Remote sensing and autonomous equipment could offer valuable information or efficiency without increasing labor.

Factors holding farmers back from adopting the technologies include cost and technical knowledge. But another risk factor for many is whether the data and connection to the farm can be protected.

While agriculture and food companies have dealt with disruptive and dangerous hacks to technology

, cybersecurity breaches in farm equipment have not happened in the United States yet.

“We haven’t seen anything of that nature happen, but we are always wanting to stay a step ahead of that for sure,” O’Brien said. “We know that with the Ukraine conflict that’s out there, we have seen Russia basically do different types of attacks on different infrastructure, so we want to make sure that our infrastructure is a step ahead of that.”

Ariana Schumacher / Agweek

Cybersecurity professionals can kind of determine peak times attackers may look to target farming equipment.

“Which is different from some areas of cybersecurity,” said Mark Spanier, associate professor and interim dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at Dakota State University. “In agriculture, you know that somebody is wanting to attack like right at harvesttime, because they can put all of their efforts in that short window of time. If they can be disruptive during that window of time, they can create all sorts of havoc.”

But having more specific target attack times can also be challenging.

“So, it’s an interesting balance of ‘I know when somebody is likely going to attack so I can put all of my efforts in’ but it also means that your attacker can put all of their efforts in at that very specific point as well, so it creates an interesting dynamic,” Spanier said.

And there are ways that farmers right now can be proactive in protecting their equipment technology.

“The onboard computer systems that they are going to have on their pieces of equipment, ensuring they are updated and with the current specs on things, as with anything you are wanting to make sure things are up to date so if there has been a known vulnerability that has emerged, that is then updated with the patches that it needs to have,” Spanier said.

Ariana Schumacher / Agweek

“Just be cognizant of what you are doing, where you leave your data, where your data exists, so if you are uploading data to the internet, just make sure that you know exactly where you are uploading to,” O’Brien said “Maybe that’s certain websites if you are working with different companies or businesses. Just be aware that you are working directly with them and maybe not through various other services.”

But overall, this research is to serve as a prevention tool.

“That kind of concern, while it’s there, just know that we are actively working on things, so we don’t want to present it as a doom and gloom situation, we are wanting to stay a step ahead,” O’Brien said. “We haven’t seen any big issues but that’s because people are actively working to stay in front of it.”

South Dakota

By hand or machine: Tabulator bans go to voters in three counties Tuesday • South Dakota Searchlight

On Tuesday, when voters in three counties decide whether to ban tabulator machines in future elections, it will be the culmination of a statewide citizen group’s multi-year movement to switch South Dakota elections to hand counting.

The votes – in Gregory, Haakon and Tripp counties – were forced by citizen-initiated petitions. Proponents of the ban claim that tabulator machines lack transparency, that election officials are breaking a state law that dictates where ballots can be counted, and that hand counting ballots is cheaper than machine counting. County auditors — the elected officials who oversee local elections — say machine counting is accurate, transparent and more efficient, and they worry a switch to hand counting could be more expensive.

Whatever the outcome, members of the South Dakota Canvassing Group plan to continue their push for hand counting.

“There’s a fire going here and will not be going out soon,” said Steve McCance, one of the lead petitioners for the Gregory County ballot question.

The nonprofit organization is part of a nationwide movement that started after the 2020 election, motivated in part by claims that the election was “stolen” from former president Donald Trump. Trump filed more than 60 lawsuits contesting either the election or the way it was administered. None of the cases succeeded, and he’s currently under criminal prosecution for allegedly attempting to subvert the election.

Polling by South Dakota News Watch and the Chiesman Center for Democracy shows that 67% of South Dakota voters accept the outcome of the 2020 presidential election, but only 20% are “very confident” that American election results reflect the will of the people.

Robert Tate, one of Tripp County’s lead petitioners, said it’s important that Americans have confidence in elections.

“If we elect an elected official and he’s not doing a good job, then we complain about him for four years and then we can vote him out,” Tate said. “But if we don’t have confidence in our elections and then our governor or our president isn’t doing a good job, we complain about how they stole the election. We don’t want that. That’s not good. ”

Several tabulator ban petitions were circulated at the county level across the state earlier this year, with some counties — including Lawrence, McPherson and Charles Mix counties — rejecting them. Officials in some counties said the petitions could conflict with federal election requirements, according to their legal counsel.

Push for hand counting focused on transparency

Aside from concerns about accuracy, South Dakota Canvassing President Jessica Pollema said the group is dedicated to transparency.

“The elections belong to the people, but they’ve been contracted out to a third party that’s blacked out an audit trail. People don’t trust that,” Pollema said. “Once there’s full transparency, people will possibly be able to trust the system again.”

South Dakota county auditors contract with Election Systems and Software, known as ES&S, a national company based in Omaha, to lease and operate tabulator machines. The company “doesn’t sign an oath,” Pollema said, and the group’s members have not been able to audit the system themselves through public records requests.

Tate said he and other members of South Dakota Canvassing asked for cast vote records and were told they “did not exist.” Activists nationwide requested such records.

A cast vote record is the electronic representation of how a voter voted (without personally identifying information), which is not a public record in the state and is only able to be produced with certain software in a few counties, officials said.

Will Adler is the associate director of the Elections Project with the Bipartisan Policy Center, which advocates for election policy reform approved by a task force of election officials aiming to make elections more secure, fair and trustworthy.

Adler said allowing cast vote records and images of marked ballots to be public records would “improve transparency a lot.” Two bills introduced during the 2024 legislative session that would have made cast vote records public — one introduced by the Secretary of State’s Office and one by Sen. Tom Piscke, R-Dell Rapids — failed to pass out of committee.

“In general, that’s a more promising avenue to move towards that would allow members of the public to understand why they can trust the tabulations,” Adler said.

State law allows for several forms of transparency in elections, including the use of poll watchers to observe the election process and public test runs of tabulators before each election to check for accuracy. Petitioners in Tripp County held a hand counting seminar the same day as the county’s tabulator test on May 30.

In 2023, the South Dakota Legislature addressed transparency by passing a bill to require post-election audits. County auditors must randomly audit at least 5% of ballots cast in voting precincts after the primary and general elections. South Dakota was one of the last few states to implement audits.

Some counties have decided to audit more than the required 5% after the primary, including Tripp, Haakon and Gregory counties.

Adler said post-election audits are a step in the right direction, though he said some other states are implementing “risk limiting audits,” which can change the audit amount based on the closeness of the race.

“This allows you to have really high confidence in a really efficient way and leveraging that human insight,” Adler said. “That allows you to have quick tabulation and quick comprehensive audits.”

Petitioners, auditors differ on cost estimates

In Haakon County, Auditor Stacy Pinney and the county state’s attorney estimates hand counting could cost more.

“I plan and prepare for the worst, but I work for the best outcome,” Pinney said.

The worst case scenario, for Pinney, is that it could take up to 15 hours for paid election workers to count the ballots, making mistakes and having to recount. County commissioners set election worker rates at the beginning of an election year. Precinct workers are required to be paid, according to state law.

The three county auditors’ estimated budgets for machine counting vs. hand counting vary, depending on how long it could take workers to count ballots. At their quickest possible pace, hand counting would be cheapest, though auditors don’t expect that.

“Honestly, we know it would never take just an hour,” said Tripp County Auditor Barb DeSersa. “Some precincts are larger than others, so it’s hard to judge how many hours it would take. It also depends on the voter turnout.”

South Dakota implemented machine tabulators in the early 2000s. Mark Nelson, one of the lead petitioners in Haakon County, was an election worker over 40 years ago and said hand counting back then “wasn’t that difficult.”

But even if it is more expensive to hand count, that money stays within the county by paying residents rather than an out-of-state corporation, said South Dakota Canvassing’s Pollema.

Pollema said hand counting can be cheaper, especially if using a specific kind of tally sheet that her group has determined can be used to count 250 ballots per hour with up to 11 races on one ballot with a trained team.

Adler said that even if auditors used the tally sheet South Dakota Canvassing Group is proposing, hand counting could still have a higher risk of error and costs.

“Regardless of how you implement it, the fact is humans are extremely bad at repetitive tasks like counting ballots,” Adler said, referencing studies on human error in different industries. “I think there’s just no way around it.”

Tripp County hand counted ballots for the 2022 election. DeSersa was awake for 40 hours straight between Election Day and the day after, with a significant amount of that time supervising hand-counters. Several races had to be recounted, sometimes three or four times that night.

Group alleges elected officials breaking law

Pollema and petitioners also claim that ballots must be counted within the precinct boundaries where they were cast, and doing otherwise is unlawful. But that statute only refers to hand counting ballots, not tabulating, said Sara Frankenstein, a Rapid City lawyer who specializes in election law.

“With the advent of automatic tabulating systems, we have a chapter in our South Dakota code that governs when those machines are used,” Frankenstein said, referencing a statute regarding the auditor setting up a central counting location (which is usually the courthouse or the county administration building) and keeping the process open to the public.

Frankenstein said the allegations are “reckless.”

“Ballots absolutely can and are required to be taken to the central location the county auditor deems,” Frankenstein said, referring to elections that include tabulator machines. “So they aren’t doing anything illegal by following those very laws.”

Whether the bans pass or not, South Dakota Canvassing will continue pushing for hand-counted elections, attending state Board of Elections meetings and supporting legislative efforts that align with their values, Pollema said.

“The people need to have the government under their watchful eye. That’s why we’re in this mess,” Pollema said. “We’ve been a little apathetic to our approach of watching our government. Now the people realize what’s going on and have decided to participate at all levels.”

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX

South Dakota

3 South Dakota counties to vote on returning to ballot tabulation by hand

Voters in at least three rural South Dakota counties are set to decide Tuesday whether to return to counting ballots by hand, the latest communities around the country to consider ditching machine tabulators based on unfounded conspiracy theories stemming from the 2020 presidential election.

The three counties, each with fewer than 6,000 residents, would be among the first in the U.S. to require old-school hand counts, which long ago were replaced by ballot tabulators in most of the country.

A number of other states and local governments have considered banning machine counting since the 2020 election, but most of those efforts have sputtered over concerns of cost, the time it takes to count by hand and the difficulty of hiring more staff to do it.

‘ELECTION INTERFERENCE’ CLAIMS MUDDY BATTLEGROUND STATE POLITICS AMID COMPETITIVE RACES

Experts say counting the votes by hand is less accurate that machine tabulation.

Supporters of the South Dakota effort aren’t deterred by such worries.

“We believe that a decentralized approach to the elections is much more secure, much more transparent, and that the citizens should have oversight over their elections,” said Jessica Pollema, president of SD Canvassing, a citizen group supporting the change.

Like efforts elsewhere, the South Dakota push for hand counting has its origins in false claims pushed by former President Donald Trump and his allies after the 2020 presidential election. They made claims of widespread voter fraud and spread conspiracy theories that voting machines were manipulated to steal the election. There has been no evidence to support such claims, but they have become embedded in many places that voted heavily for Trump.

The citizen initiatives in South Dakota to prohibit tabulating machines are set to appear on Tuesday’s primary ballot in Gregory, Haakon and Tripp counties. Similar petition efforts for future measure votes are underway in more than 40 other counties in the conservative state, Pollema said. At least four counties have rejected attempts to force hand counting.

Earlier, the Fall River County Commission voted in February to count ballots by hand for the June election, and Tripp County counted its general election ballots by hand in 2022.

From left, Jessica Pollema speaks Oct. 19, 2023, at the Military Heritage Alliance in Sioux Falls, S.D. She is a co-founder of South Dakota Canvassing and a leading advocate of getting rid of the machines in favor of hand counting ballots in South Dakota. (Stu Whitney/South Dakota News Watch via AP)

If the measure passes Tuesday, Gregory County Auditor Julie Bartling said the county will have to increase the number of precincts to lessen the burden of hand counting. That will force it to buy more assisted voting devices for disabled voters. The county also will face the difficult task of hiring more election workers.

Bartling, who runs elections in the county, opposes the initiative and said she has “full faith in the automated tabulators.”

Todd and Tripp County Auditor Barb DeSersa said she also opposes attempts to require hand counting of all ballots because the process isn’t as accurate. She said the 2022 hand count left election workers exhausted.

“I know the ones that have done it the last time didn’t want nothing to do with it this time, so I think once they do it once or twice, they’ll get tired of it, and it’ll be harder to find people to volunteer to do that,” DeSersa said.

DeSersa’s office estimated it would cost $17,000 to $25,000 for elections in Tripp County to be counted by hand, compared to about $19,000 to $21,000 using tabulators. Haakon County Auditor Stacy Pinney said she initially estimated hand counting will cost between $750 and $4,500, but “overall, an election cost is hard to determine at this point.”

According to a state attorney’s analysis for Haakon County, it would take two election workers using a tabulator three to four hours to count all the ballots. It would take 15 to 20 election workers between five and 15 hours to do a hand count, depending on the number of contested races.

The three counties have a combined 7,725 active registered voters, according to a statewide report.

Republican state Rep. Rocky Blare, who lives in Tripp County, said he will vote against the measure.

“They can’t prove to me that there’s been any issues that I think have affected our election in South Dakota,” Blare said.

Secretary of State Monae Johnson, a Republican, expressed confidence in tabulating machines, noting they have been used for years. In a statement, she pointed to “safeguards built in throughout the process and the post-election audit on the machines after the primary and general election to ensure they are working properly.”

The June election will be the first with a post-election audit, a process included in a 2023 state law. It involves hand counting all the votes in two races from 5% of precincts in every county to ensure the machine tabulation is accurate. Johnson’s office said there was no evidence of any widespread problems in 2020 or 2022. One person voted twice, she said, and was caught.

After repeated attacks against machine-counting of ballots in the 2020 presidential election, Dominion Voting Systems last year reached a $787 million settlement in a defamation case against Fox News over false claims the network repeatedly aired. The judge in that case found it was “CRYSTAL clear” none of the claims about Dominion’s machines was true, and testimony showed many Fox hosts quietly doubted the claims their network was airing.

Since 2020, only a few counties have made the switch to hand counting. In California, officials in Shasta County voted to get rid of their ballot tabulators, but state lawmakers later restricted hand counts to limited circumstances. Officials in Arizona’s Mohave County rejected a proposal to hand count ballots in 2023, citing the $1.1 million cost.

David Levine, a former local election official in Idaho who is now a senior fellow with the Alliance for Securing Democracy, said research has shown hand counting large numbers of ballots is more costly, less accurate and takes more time than machine tabulators.

“If you listen to conspiracy theorists and election skeptics throughout the U.S., one reason the 2020 election was illegitimate was because of an algorithm. Hence, if you take computers out of the voting process, you’ll have a more secure election,” Levine said. “The only problem: it’s not true.”

While some areas do count ballots by hand, mainly in the Northeast, it typically happens in places with a small number of registered voters. Hand counts are common during post-election tests to check that machines are counting ballots correctly, but only a small portion of the ballots are manually checked.

Election experts say it’s unrealistic to think workers in large jurisdictions, with tens or hundreds of thousands of voters, could count all their ballots by hand and report results quickly, especially since ballots often include multiple races.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

“The issue is that people aren’t very good at large, tedious, repetitive tasks like counting ballots, and computers are,” Levine said. “Those who believe otherwise are either unaware of this reality or choose to ignore it.”

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoRead the I.C.J. Ruling on Israel’s Rafah Offensive

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoHoping to pave pathway to peace, Norway to recognise Palestinian statehood

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoLegendary U.S. World War II submarine located 3,000 feet underwater off the Philippines

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoFamilies of Uvalde school shooting victims sue Microsoft, Meta and gunmaker

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoDefense Secretary Lloyd Austin to undergo nonsurgical procedure, Deputy Kathleen Hicks will assume control

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoHunter Biden attends pre-trial hearing in Delaware court on federal gun charges

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoHere are three possible outcomes in the Trump hush money trial : Consider This from NPR

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoPrimate remains on the loose in South Carolina | CNN