Detroit, MI

How feds took down a Detroit gang linked to COVID pandemic relief fraud

DETROIT – Felony gangs in Detroit have a fame for road violence, however one gang tried shifting its crimes from the streets to the web.

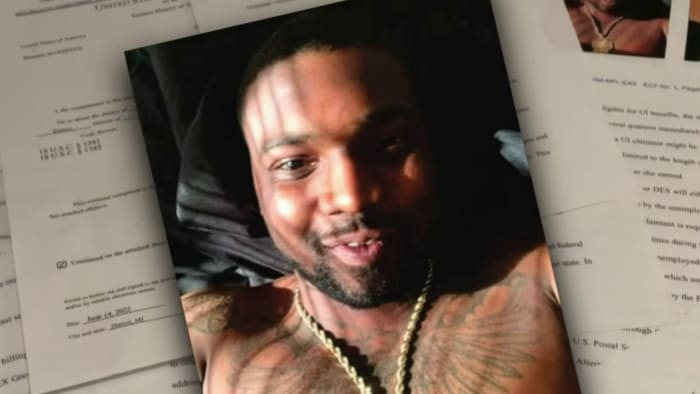

That was till one alleged gang member’s flashy bling, amongst different issues, obtained them busted. A photograph reveals Brandon Bowditch cashing out stolen COVID reduction cash at an ATM, in accordance with federal brokers.

Bowditch was carrying a “fortunate” four-leaf clover pendant. Investigators consider the pendant the 31-year-old Detroit gang member was carrying was paid for with stolen COVID reduction cash.

“Gangs in Detroit are gonna go the place the cash is,” Detroit Crime Fee Govt Director Andy Enviornment mentioned.

Federal investigators mentioned a road gang referred to as “Don’t Fear About It” used the web to steal almost half one million {dollars} in COVID reduction cash from all around the nation.

Learn: Feds: Dearborn Heights man buys seaside apartment with COVID reduction cash; spouse runs $10.6M pharmacy scheme

How investigators say the rip-off went down

Federal investigators mentioned gang members used stolen identities of actual Individuals, went on-line and utilized for COVID pandemic unemployment insurance coverage in no less than eight states.

These states embody Michigan, Arizona, California, Hawaii and even in U.S. territory Guam.

Profit cash, within the type of debit playing cards, was mailed to the gang members’ Detroit houses. The playing cards had been then cashed out at space ATMs.

“Actually the unemployment insurance coverage system had various methods for these guys to steal cash,” Enviornment mentioned.

Enviornment is a former FBI agent and mentioned the case doesn’t shock him in any respect.

“However they get caught. They’re not as sensible because the system,” Enviornment mentioned.

In line with courtroom paperwork, the gang used the identical Detroit telephone numbers and addresses for unemployment profit cash in a number of states. Federal officers mentioned that led to the bust of Bowditch.

Bowditch is presently out on bond dealing with mail fraud and wire fraud.

You possibly can view a PDF of the prison grievance beneath:

Have a case you’d like us to look into? Attain the Native 4 investigative workforce at 313-962-9348, or e mail Karen Drew at kdrew@wdiv.com.

Copyright 2022 by WDIV ClickOnDetroit – All rights reserved.

Detroit, MI

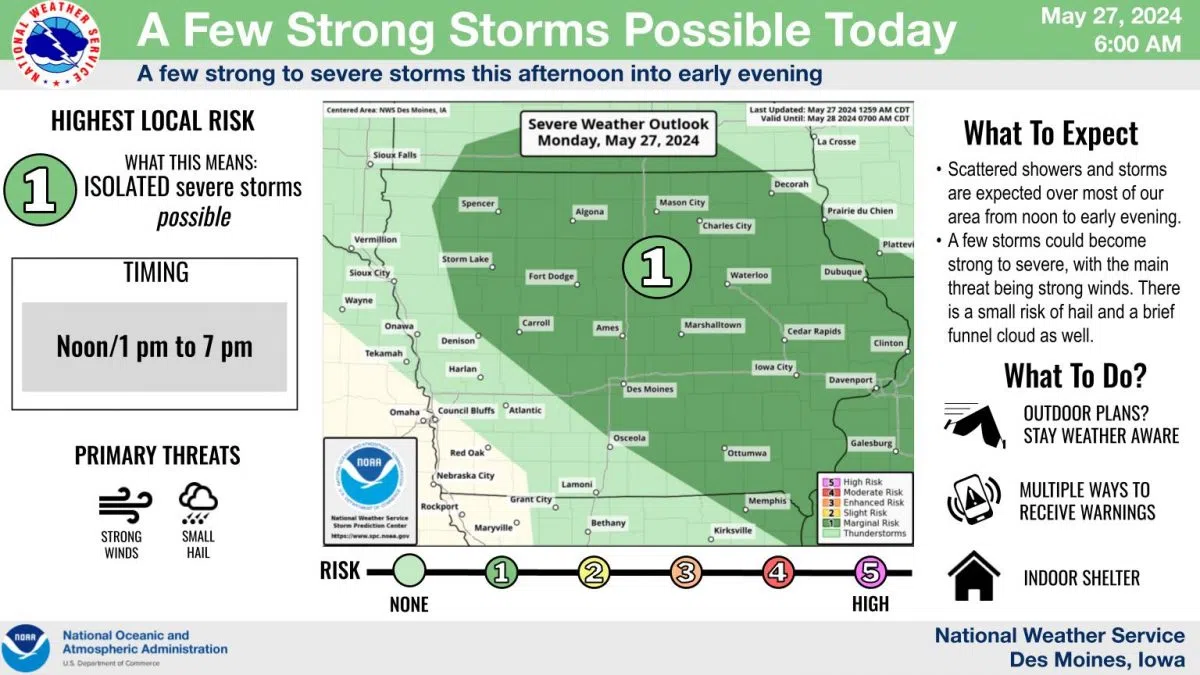

Memorial Day off to rainy start, some roads flooded, as a drier afternoon expected

Memorial Day is off to a wet start, with a steady stream of rainfall across southeast Michigan that started early Monday morning.

The rain snarled some Detroit roadways, according to Michigan Department of Transportation updates, causing flooding on the northbound Interstate 75 ramp to eastbound Davison freeway and flooding on westbound I-696 near Evergreen Road, blocking one lane.

But the National Weather Service forecasts that the storms should roll out of the area by the afternoon, with a chance of some windy conditions.

It’s unclear if the weather will affect the Movement Festival’s third day of music in Hart Plaza. On Saturday, storms led to a lengthy pause in festivities, but the partying later resumed. Monday’s first acts are scheduled to take the stage at 2 p.m.

Contact Lily Altavena: laltavena@freepress.com.

Detroit, MI

Don’t Call It a Comeback for Detroit

The Detroit Lions have not won a championship since 1957. That same year, Detroit’s population grew for the last time—until last year. The Lions still haven’t won the Super Bowl, but they’re gaining momentum. And, for the first time since 1957, Detroit’s population is growing.

The increase was modest; the U.S. Census Bureau reported a 1,852-person bump in the Motor City’s ranks. Still, that’s more than can be said for cities like Baltimore, Philadelphia, Chicago, and New Orleans, where populations declined over the same period. Whether Detroit’s growth is a one-off or the beginning of the comeback often forecasted but never imminent, only time will tell. Detroit will have to prove itself capable of overcoming the factors that led to its demise.

Founded by French fur traders and missionaries, Detroit has long been subject to demographic change. The once-small city was a bargaining chip for great powers through the latter half of the 18th century, traded from French to British to American hands, often with incursions from regional Native American tribes. Located along the waterway connecting Lake Huron to Lake Erie, Detroit was well-positioned for the growth of the young nation’s industry.

Over the next century, European immigrants came to Detroit, mostly from Poland, Ireland, and Germany. Unlike residents of most major American cities, Detroit’s citizens lived mainly in single-family homes rather than tenements or row houses—immigrants included. But, as was common, immigrants settled in ethnically homogeneous neighborhoods, giving rise to Poletown, Germantown, and Greektown within the city limits.

When Henry Ford transformed Detroit into Motor City, he hired factory workers from among the city’s immigrant population, attracting labor with the generous $5 workday. But the growth of Ford Motor Company soon outpaced the growth of Detroit’s immigrant population. The automobile industry needed more factory workers, but fewer Europeans were moving to the city due to several restrictive immigration bills in the 1920s. Looking for workers domestically, Ford began hiring black Americans who had moved north in search of work and a reprieve from the Jim Crow South.

Ford’s continued expansion would not just change Detroit economically but demographically, culturally, and geographically. By 1930, Detroit’s black population grew 25-fold to 150,000. Like European immigrants before them, black Americans lived in ethnically homogeneous neighborhoods in the city.

And as both money and workers poured into Detroit, rapid industrialization heightened racial tensions in the city. Searching for available land and lower prices, companies began building new factories on the outskirts of Detroit. And as companies moved out of downtown, so did their employees. A 1932 population survey concluded that “the outward expansion of the city has pushed suburban development farther and farther away from the down-town section. As a result…Detroit is deteriorating within the heart of the city itself.”

But the deterioration was slow—for a while, at least. Detroit residents moved to subdivisions on the city’s outskirts, many of which advertised themselves as havens from the city’s ethnic integration. Some new neighborhoods offered buyers assurance that, “ten years from today, the neighborhood will be just as desirable as it is today,” not so subtly hinting at race occupancy restrictions for the new developments.

Property owners in Detroit were concerned about the same thing. Those who didn’t, or couldn’t afford to, move away became wary of fluctuations in property value. With the financial disaster of the Great Depression still in recent memory, white, working-class homeowners were skeptical of anything that could jeopardize their property value—including racial integration. Where suburban homeowners had recourse to realtors, urban homeowners often took matters into their own hands, heightening racial tensions.

By 1957, more people were leaving Detroit than were moving in, and the black population remained fairly concentrated in central neighborhoods. Then, a decade later, came the summer of rage.

Of the 158 race riots that exploded in cities across America during the summer of 1967, Detroit’s riots were the bloodiest. Over five days, 43 people were injured, 7,2000 arrested, and more than 2,500 buildings were looted or destroyed. Michigan’s governor sent in the

The hemorrhage of white residents to the suburbs turned into abject flight. In 1967, 47,000 people left Detroit, headed for the suburbs. The following year, 80,000 people left. In the next decade, Detroit public schools saw a 74 percent decrease in the number of white students enrolled. Following white flight, Detroit became a majority-black city.

As Detroit’s population plummeted, neighborhoods were abandoned, and once-bustling subdivisions became blighted. Crime spiked, heroin use grew, and gun violence became commonplace. For decades, Detroit went up in flames every Halloween when arsonists torched hundreds of homes on “Devil’s Night,” as it became known.

By the time deindustrialization created the Rust Belt, Detroit had already fallen. Ironically, the very industry that built the city had also served as a vehicle for displacement and inflamed racial conflict.

As the city’s demographics shifted, so too did its politics. Activists looked to profit from stoking racial tensions, like lawyer and black labor organizer Kenneth Cockrel Sr. In one case, Cockrel was able to convince a jury that his defendant — who had taken an M-1 carbine to his shift at a Chrysler plant and killed two foremen and a fellow worker — was “not guilty by reason of insanity as a result of racism and conditions inside the plant.” As Bill McGraw wrote in the Detroit Free Press, “With such unlikely victories, much of white Detroit was incredulous — and angry — that black radicals were overthrowing the old order downtown.”

In 1973, Coleman Young, a former black radical, ran for mayor against police commissioner John Nichols. Young won the election by three points, supported by the majority of black voters but only 10 percent of white voters.

As time went on, white residents weren’t the only ones who left Detroit. From 2000 to 2020, Detroit lost a third of its black population, undergoing the greatest loss of black residents in any American city. In 2010, 82 percent of Detroiters were black—the highest ratio in the nation—compared to 77 percent today.

Detroiters left, but their houses still stood, creating long stretches of neighborhood blight. Houses in the city sold for as little as $100 in 2011. Mayor Mike Duggan has knocked down over 25,000 blighted houses, aiming for a goal of “next to zero” abandoned homes by the end of next year.

Since 2013, when Duggan first ran for mayor, he claimed that Detroit would gain population under his leadership. Whether he can sustain the growth—or ameliorate frustrated Detroiters who accuse investors of racist gentrification—is another question. As small numbers of white residents return to the city, some black Detroiters feel displaced by new commercial and residential investments. Some are still resentful that white flight to the suburbs crippled Detroit’s tax base, throwing the city into decades of poverty and underfunded resources.

But white people certainly aren’t the only ones moving to Detroit. As mayor, Duggan established an office of immigrant affairs headed up by Fayrouz Saad, who was tapped by Governor Gretchen Whitmer to run Michigan’s immigration policy. Saad’s department administers Whitmer’s Newcomer Rental Subsidy program, which provides up to $500 a month in rental assistance for immigrants and refugees in hopes of reversing Michigan’s decline in population. Program applications can be completed in English, Arabic, Dari, Haitian Creole, Kinyarwanda, Pashto, Spanish, and Ukrainian.

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

In the years since white flight, Detroit has experienced a new wave of immigration. Immigrants from Middle Eastern countries have flocked to the region in recent years, giving the Detroit metro area the largest Muslim population in the nation. Dearborn, which lies just outside of the Detroit city limits, recently became America’s first majority-Muslim city.

Inside Detroit, too, Arab-Americans have moved into the neighborhoods founded by European immigrants. For years, Polish-Americans lived in Hamtramck, creating a small enclave of Polish culture. In 2021, however, Hamtramck elected a completely Muslim city council, and Amer Ghalib became the first mayor of Hamtramck in 100 years without Polish heritage.

Demographic change has long been the story of Detroit, but the last seventy years have shown the perils of that change. An increase in population could be the harbinger of urban renewal, though it’s ultimately more likely to bring about heightened ethnic tensions. And if Dearborn and Hamtramck are indicators, the future of Detroit could be shaped less by black-white dynamics and more by the burgeoning conflict between Americans and anti-western values.

Detroit, MI

Electronic music fans celebrate Detroit’s heritage, influence at Movement festival

Detroit — Thousands traveled to the birthplace of techno music Memorial Day weekend to celebrate its Detroit heritage and influence at the Movement Music Festival.

“It’s one of those events that everybody in the city looks forward to every year to kick off the summer here in the city … contributing to the city’s art, culture, and legacy,” said Morin Yousif, a spokesperson for Paxahau, which is producing the event at Hart Plaza in downtown Detroit.

“Day 1 attendance was one of the best we’ve had in recent years, the excitement of the first day along with great weather were major contributors to this,” Yousif said.

The Movement Music Festival is one of the longest-running dance music events in the world, going back to the 2000s.

Micheal Leuffen of Berlin, Germany, was in town for work at Carhartt Work In Progress and decided to get a ticket to stroll around downtown Detroit during the festival. He took a photo of the statue in front of the Coleman A. Young building across the street.

“I’m very much linked to musicians in the city,” he said, adding that he’s been to the festival three times. “I’m coming from Europe, so we have a lot of electronic festivals, DJ-oriented festivals, but I think it’s one of the best in the U.S. and probably the only one where you attract so many people from abroad.

“I know also a lot of people from Germany who are also coming here. It’s really nice for the city as musicians from here say it’s their Christmas. It’s also linked to the heritage of music from Detroit. … And then you have all these little things happening around with new musicians, so it’s not only Movement, it’s the little parties that go around. It’s musically very interesting and true to the world,” said Leuffen, 53.

Kira Lesser, 39, and her partner Tyler Carr brought their young daughter to the festival from Ann Arbor. Carr has been coming to the event for 10 years.

“It’s house music. It’s Detroit. I listen to it. I make it. I used to be a DJ,” Carr said.

Salat Carrillo, 17, and her sister Sabrina, 26, booked a four-day trip to Detroit from Maryland to see their favorite DJ I Hate Models perform Sunday night.

“I think every region always dresses differently. I never been to a festival out here in Michigan. We always stay on the East Coast obviously, so I’m really excited to see what everyone wears,” Sabrina Carrillo said.

mjohnson@detroitnews.com

@_myeshajohnson

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoIs Coppola’s $120M ‘Megalopolis’ ‘bafflingly shallow’ or ‘remarkably sincere’? Critics can’t tell

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump predicts 'jacked up' Biden at upcoming debates, blasts Bidenomics in battleground speech

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoA bloody nose, a last hurrah for friends, and more prom memories you shared with us

-

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24038601/acastro_STK109_microsoft_02.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24038601/acastro_STK109_microsoft_02.jpg) Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoMicrosoft’s Surface AI event: news, rumors, and lots of Qualcomm laptops

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week ago‘The Substance’ Review: An Excellent Demi Moore Helps Sustain Coralie Fargeat’s Stylish but Redundant Body Horror

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoVideo: A Student Protester Facing Disciplinary Action Has ‘No Regrets’

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoIndia’s biggest election prize: Can the Gandhi family survive Modi?

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoPanic in Bishkek: Why were Pakistani students attacked in Kyrgyzstan?