Lifestyle

Barbara Walters forged a path for women in journalism, but not without paying a price

In 1976, Barbara Walters became the first woman to co-anchor a national news show on prime time television. She was only in that role for two years, but her arrival changed news media.

“She’s such a consequential figure for journalists, not just for women journalists,” biographer Susan Page says. “The path she cut is one that many of us have followed.”

Page is the Washington bureau chief at USA Today and the author of The Rulebreaker: The Life and Times of Barbara Walters. Though they never met, Page says speaking to hundreds of Walters’ friends and colleagues and watching hours of her interview tapes gave her a sense of her subject.

Page describes Walters as a fearless journalist who didn’t shy away from controversy or tough questions. She battled sexism throughout her career — especially from her first co-anchor, Harry Reasoner, who, Page says, scowled at Walters’ presence and tracked how many words she spoke on-air compared to him.

After leaving the nightly news post, Walters became known for her long-form interviews. Her conversations, which blended news and entertainment, featured a wide range of subjects, including Fidel Castro, Vladimir Putin, Richard Nixon, Monica Lewinsky, Michael Jackson and Charles Manson. In 1997, she created The View, a daily talk show with an all-women cast of co-hosts.

“One thing that I thought was interesting about Barbara Walters is that she thought all sorts of people were interesting and worth talking to,” Page says. “She really expanded the world of interviews that [national] journalists were doing to include not just presidents, but also notorious murderers.”

For Page, Walters’ success feels personal: “It never occurred to me when I was looking at a career in journalism that I couldn’t do big interviews with important people because Barbara Walters did. … Even though I’ve been in print journalism, not TV journalism, I benefited from the battles that Barbara Walters fought.”

Interview highlights

On her family life that drove her to work hard

Understanding the source of her drive was hard to understand and I think crucial. And I decided after doing all this reporting about her that, that there was a moment that ignited the drive in Barbara Walters, and that was when her mother called her and told her that her father had attempted suicide. Her mother didn’t call an ambulance. … [Barbara] called the ambulance. [Barbara] rode in the ambulance with her father to the hospital. And she realized almost in an instant that while she was going through her first divorce, she didn’t really have a career that as of that moment, she was going to be responsible for supporting her father, who had just tried to commit suicide, her mother, who was perpetually unhappy, and her special needs sister. And that that was going to require her to get serious, to make some money and to sustain that. She always had the sense that it could all disappear in an instant.

On news co-host Harry Reasoner’s hostility about working with Walters

He was so openly contemptuous of her on the air that the director stopped doing two shots. That is a shot where you could see Harry Reasoner watching Barbara Walters speak because he was always scowling. It was so bad that they got many letters from mostly women viewers complaining about how she was being treated. … It was really an untenable situation and one that took a while to unravel, and it was one that unnerved Barbara Walters. It was the one time in her career when she thought perhaps she had made an error so great that she would not recover. She said that she felt not only like she was drowning, but that there were people trying to hold her head under the water.

On a turning point in her career, when she interviewed Fidel Castro

So this was in 1977. She was still officially the anchor [of ABC Evening News], but things were not going well. And she landed this interview with Fidel Castro, who had been interviewed only infrequently by Western journalists. And … she got in a boat and crossed the Bay of Pigs with him. He drove his jeep across the mountains with her sitting next to him, holding aloft his gun to keep water from splashing on. It was a great interview. A very tough interview. She asked him about freedom of the press, which didn’t exist in Cuba. She pressed him on whether he was married. This was a question that he had refused to answer. … So he finally gave up and answered it and said formally, no. So it was a great interview and it was a comeback interview for her. It both showed what she could do in an interview, and it made her feel more confident again.

YouTube

On her interview with Richard Nixon when she asked him if he wished he burned the Watergate tapes

That was in a particularly difficult interview, because the only way the Nixon people agreed that she could do it was to do it live. There was no cutting out some extraneous matter to get that last question in, she had to be incredibly alert about controlling the interview so that she would have time to ask that question. And the other thing that we should know about that question is she always wanted to ask the question that everybody wanted to hear, even the toughest question possible, like would you have burned the tapes? She wanted to ask the one that people wanted to hear the answer to. That was one of [her] great gifts. And she figured out that by preparing for hours and hours and writing down proposed questions on small 3×5 cards and shuffling them and revising them, and finally having them typed on 5×7 cards to ask. She would let an interview go where it went. She didn’t always follow the cards, but she always had a plan in mind for how she wanted to get the interview started. What she wanted to do in the middle and the thing that she wanted to do at the close to give it a real kick.

On her friendship with Donald Trump

They were transactional friends. She went to his wedding. He went to the celebration of her third marriage. He was often a guest on The View when The View started in 1997. He was then a real estate developer in New York. And if they were short a guest, they could call up Donald Trump and he would come over and be on the show or even do a cameo skit. … And, in fact, one ABC executive told me, when Donald Trump got involved in politics, that there was a feeling, some discomfort, that she had given him a platform and a legitimacy that maybe he wouldn’t have had otherwise.

YouTube

On her preparation for her infamous Monica Lewinksy interview

Barbara Walters was working on asking the questions, but at the same time, Monica Lewinsky was working with her team on how to answer the questions. The question that gave the Monica Lewinsky team the most trouble was that question, “Do you still love him?” Because at the beginning of their practice sessions, she said yes. And then she said she couldn’t say no because she did love him. And she loved him some of the time. And, they warned that that was not an effective answer to have. So you hear her, in this interview giving the answer they had worked out, which was no. But then in her follow up, she does acknowledge that sometimes she does still have warm feelings for him. On the Barbara Walters side, they worked a long time on what the closing question would be, because that’s a powerful position in an interview like this, that last question. And they settled on, “What will you tell your children?”

YouTube

On Gilda Radner’s impression of her as “Baba Wawa,” mocking the way she spoke

She was wounded when she heard this. For one thing, even though there was this exaggerated lisp that Gilda Radner used, nobody had any doubt who she was parodying. And, Barbara Walters had this speech anomaly. She called it a bastard Boston accent. Other people called it a lisp. Whatever it was she had tried, she’d gone to voice coaches early in her career to try to fix it, and it failed. So her feelings were hurt when the skit was done on Saturday Night Live. Now, it also made her famous. She came to terms with it, but I think she always found it kind of hurtful. … When Gilda Radner died … Barbara Walters wrote a sympathy note to her widower, Gene Wilder, expressing sympathy on her death, and signed it, “Baba Wawa.”

On her reluctant retirement

She worked into her 80s. … When she was in her 70s, she was working at a time when most women had been involuntarily retired. So she worked as long as they would keep her on the air. But as she started to sometimes miss a step, there was concern that she would embarrass herself or undermine some of the professional work she had done. … The people at ABC convinced her it was time to retire. And then CNN came in with a secret offer to put her on the air at CNN, which she was considering when her friends came back and said, no, it’s time. … There was a grand finale on The View, where two dozen women prominent in journalism came and paid tribute to her. And on her last, big show on The View. And when she was backstage afterwards, one of them came up and said … “What do you want to do in your retirement?” And Barbara said, “I want more time.” Meaning I want more time on the air.

On if she was happy

I asked 100 people who knew her that question: Was she happy? And a few people said yes. Joy Behar of The View said “happy-ish,” which is not a bad answer, but most people said while she was proud of what she had done and that she loved the money and the prominence that she had won, that she paid this huge price on the personal side — she had three failed marriages. She was estranged for a time from her only daughter. She never lost that feeling that she was always competing and could never stop and be content. So she had the most successful possible professional life, but I think she had kind of a sad, personal one.

Thea Chaloner and Joel Wolfram produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Beth Novey adapted it for the web.

Lifestyle

Larry Demeritte will be the first Black trainer in the Kentucky Derby in decades : Consider This from NPR

For sponsor-free episodes of Consider This, sign up for Consider This+ via Apple Podcasts or at plus.npr.org. Email us at considerthis@npr.org.

May 1988: General view of the Kentucky Derby at Churchill Downs in Louisville, Kentucky.

Mike Powell/Allsport/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Mike Powell/Allsport/Getty Images

May 1988: General view of the Kentucky Derby at Churchill Downs in Louisville, Kentucky.

Mike Powell/Allsport/Getty Images

1. Saturday marks the 150th running of the Kentucky Derby at the Churchill Downs Racetrack.

Crowds will cheer as the thoroughbreds thunder around a mile and a quarter track. The race itself only lasts around 2 minutes, but the tradition runs deep in America.

Excitement ramped up a few days ago as post positions were assigned to the horses in this year’s race. The last horse to be called was West Saratoga – a longshot gray thoroughbred. Its owner Harry Verruchi credits veteran horseman Larry Demeritte for finding the horse, saying that Demeritte “can look to a horse and see more than normal people can see.”

Larry Demeritte is a horse trainer in his 70s. In an interview with NPR’s Scott Detrow, he said he’s been around horses for as long as he can remember.

“My dad was a horse trainer and he put me on the horses back when I was pretty young… I know them before I know myself, and I know I wanted to be in the horse industry,” he remembers.

“I said ‘Well, I don’t want to be a jockey because their careers don’t last long. I know I’m not going to be a worker, so I have to be a horse trainer because I could do that til’ I die.’”

2. Horse racing wasn’t always so exclusive.

Demeritte is the first black trainer to participate in the Derby in 35 years, and the first person ever from the Caribbean to do so. Before 1989, there hadn’t been a Black trainer since 1951. Black trainers, jockeys, and grooms are a rarity at the Derby these days, but that wasn’t always the case.

The first Kentucky Derby was in 1875. Oliver Lewis won the first Kentucky Derby, and his horse was trained by Ansel Williamson, both of whom were Black men.

Ronald Mack is the founder of the Legacy Equine Academy, and in a Kentucky Educational Television documentary about the history of Black horsemen, he noted that 15 of the first 28 winners of the Kentucky Derby were Black jockeys, “And so there was dominance and prominence in the industry.”

Black people played a key role in the early history of the Kentucky Derby, but they were forced out through Jim Crow segregation. Today, Demeritte hopes the sport can open its doors to more people:

“We need to sell our sport better than we do… We need to form more syndicates because it’s getting pretty costly now to own a racehorse. It’s like any other sport… car racing and all of them, they all have syndicates…so [many] sponsors. I feel like that’s what we have to do to let the middle class know in America that it’s not a sport of kings. Anyone can play it, and the reward is so great when you have success in it.”

3. Persisting through illness.

Demeritte has faced three separate cancer diagnoses over the years, as well as a rare disease called amyloidosis. Despite struggling with his health, he says he’s kept a positive outlook through his faith in God.

“I feel like I’m here for a purpose. And I think this is my purpose, the opportunity to make a difference in someone’s life… Anything is possible. But you have to work at it, you know? That’s the way I look at life.”

He says he never lets his illness stop him from being focused on the task at hand. And looking toward this weekend, he’s excited for the big day, and he’s confident about West Saratoga’s chances.

“When you do things you love, it’s nothing tough about it. Get that smile put on your face when you see a horse train good that morning for you. And that’s the good thing is Saratoga, he don’t have too many bad days,” he says.

“He’s such a cool horse.”

For sponsor-free episodes of Consider This, sign up for Consider This+ via Apple Podcasts or at plus.npr.org. Email us at considerthis@npr.org.

This episode was produced by Jonaki Mehta.

It was edited by Jeanette Woods.

Our executive producer is Sami Yenigun.

Lifestyle

Costa Mesa Police Chase Down Juveniles Accused of Stealing Car on Foot

TMZ.com

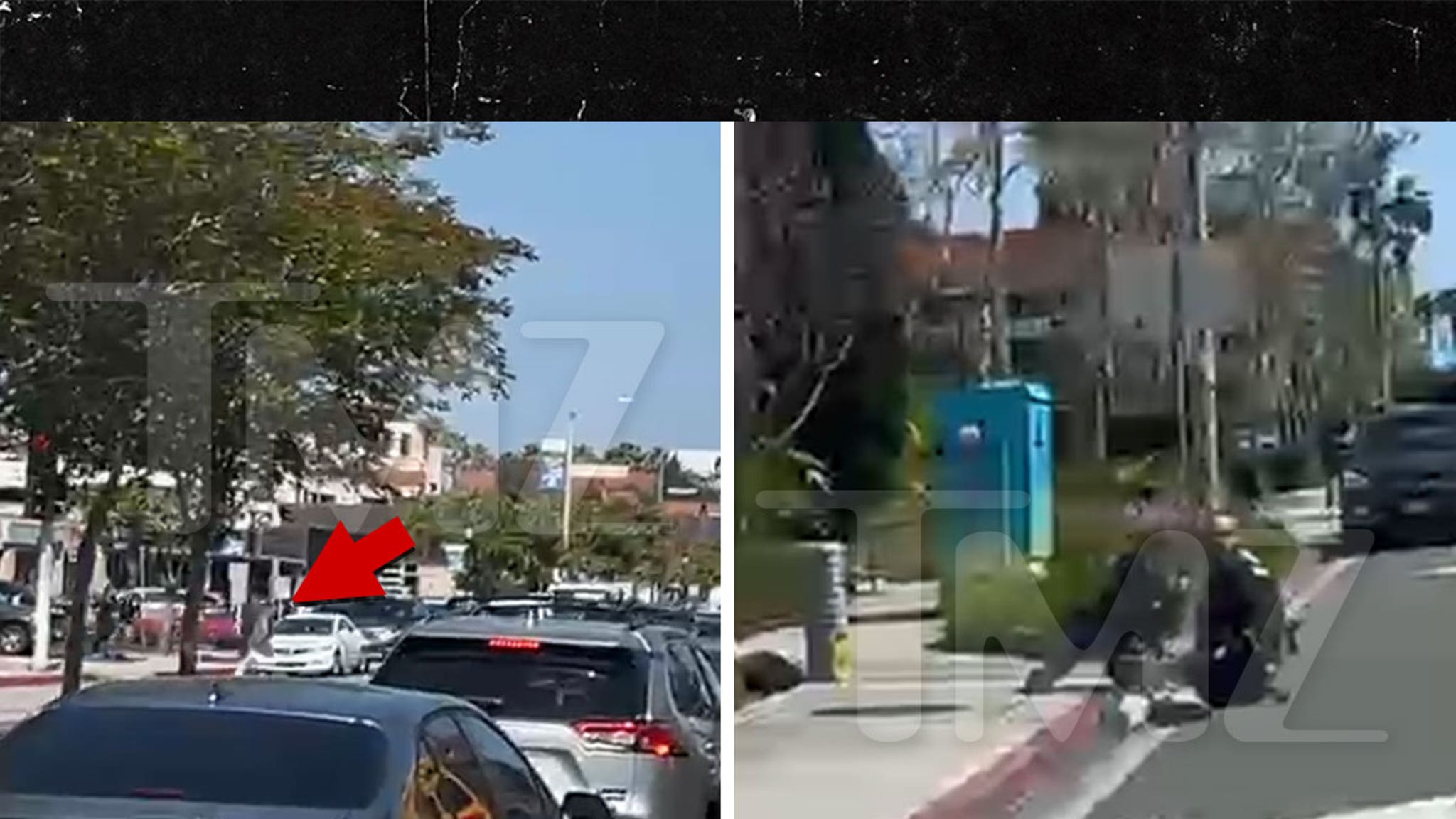

Cops in Orange County got their exercise in to end the week — they had to chase down a handful of alleged juvenile delinquents accused of jacking a car … and the video’s wild.

Costa Mesa PD tells TMZ … officers came across a vehicle that had been reported stolen Friday in the middle of the day — and when they tried initiating a stop, we’re told the car didn’t come to a stop … so the police had to give chase.

We’re told there was a short pursuit, which ended with the subjects of the vehicle bailing on the car … and cops having to chase them down on foot — something captured on camera.

TMZ got a hold of the footage … and yeah, it’s pretty intense — you can see the whole thing.

Check out the clip … you can see what looks to be a few people taking off running through the road, where a ton of cars are stopped at a light … with what looks like a lot of police activity on the scene — including multiple cruisers and even helicopters in the sky too.

The cops that end up going after these people appear to have their weapons drawn — but luckily, no shots are fired … and in the end, it looks like they were able to nab the suspects.

CMPD tells us three people were taken into custody … and we’re told they were all teens. No word on what charges they might’ve been booked on at this point.

Lifestyle

Why Jenny Slate sometimes feels like a 'terminal optimist' : Wild Card with Rachel Martin

Jenny Slate says she’s always looking for the light in the dark.

Photograph by Emily Sandifer; illustration by NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Photograph by Emily Sandifer; illustration by NPR

Jenny Slate says she’s always looking for the light in the dark.

Photograph by Emily Sandifer; illustration by NPR

Welcome to Wild Card from NPR, where host Rachel Martin asks guests randomly-selected questions from a deck of cards. Tap play above to listen to the full podcast, or read an excerpt below.

I spent a lot of years hosting news shows at NPR and I got really tired of covering stories that reinforced how bad everything in the world was.

Basically, I was burned out. But it was also bigger than my job. My dad died unexpectedly and my mom had died a long time ago, so I felt empty and sort of lost. And I felt this urgency. All I wanted to do was think through really big questions about what it means to be alive. What experiences made us who we are? What lessons do we have to learn over and over? What beliefs help us make sense of the world?

And when I started opening up about this to friends, I realized that a lot of other people were also swimming around in these kinds of questions. So I thought, what if we talked about this stuff out loud? And wouldn’t it be cool to do it with people who, on the outside, seem like they’ve got their existential act together? But that’s a little intimidating. So we came up with this idea for a game to make it easier.

This is the way it works: we made this little deck of cards with really big questions on them. My guests pick cards from the deck at random. And then they answer the questions.

And I’m telling you, it’s amazing what happens. They start talking about ideas and experiences they haven’t talked about before, and then, I’m doing the same thing. I always leave these conversations feeling better — feeling that no matter how different we are, we’re all working through the same stuff.

And my hope is that this is going to happen for you too. That you’ll find yourself thinking about these questions and how they fit into your own life.

And I couldn’t have dreamed up a better guest to get things started than Jenny Slate. She is one of the deepest, most interesting comedians out there, in my opinion.

That comes out in her stand up and her movies, especially Marcel the Shell with Shoes On, which is one of the weirdest, most random, beautiful movies. You might know her from Obvious Child or for her role as Mona-Lisa Saperstein from Parks and Recreation.

This year, Slate released her latest comedy special called Seasoned Professional, which, at this point in her career, she really is — even if she’s still figuring out life like the rest of us.

The trailer for Jenny Slate: Seasoned Professional.

YouTube

So, let’s shuffle the Wild Card deck and draw our first question. Which is…

Question 1: What’s an ordinary place that feels extraordinary to you because of what happened there?

Jenny Slate: This sounds maybe gross or something, but I really feel that way about our bedroom in Massachusetts. And not because I’m like, you won’t believe what went down in here [laughs].

My husband is someone I met as a stranger and I really felt that I would not see him again. I thought about him a lot and I heard from another friend about where he lived in Massachusetts. And it felt to me that he lived almost in another dimension.

And I just remember the first time that I went to sleep in his bedroom and I was like, wow, this is a real place. It’s kind of like seeing the Eiffel Tower, like, I can’t believe it is real. And even though we live in that house together now, I still feel that way.

It’s a house that was built for his great grandmother, and when he lived there by himself it was filled with, like, a hundred years of stuff. And it felt very bachelor-y, like Dickensian bachelor-y. Like, there’s a taxidermied tortoise in here and heavy draperies from before. And now that we live there, it’s very sparse. I prefer a more Shaker aesthetic.

Rachel Martin: You had been married before. Did something have to change in you to make this relationship work, or was it just timing?

Slate: I couldn’t stop the timing of falling in love with him. And it was right for both of us to fall in love. But while walking down that path, I was very aware that I was injured. And I had to learn to trust — not just the big things, like I hope this person won’t lie to me, but also, I hope they won’t tell me they’re having one experience while having another. I hope they won’t secretly resent me for the things that they first felt were attractive about me.

As a performer, you want to shine your power out and that can be really attractive to people. But then all of a sudden they can get angry about it. That it’s not just for them. And so I do think that I really had to do a lot of work on my side of the problem in terms of learning to trust self-worth issues. But I am also an operatic romantic. I just love love, and that really helps.

Question 2: What is something you think about very differently today than you did 10 years ago?

Slate: Dressing. Not salad dressing, I’ve always loved it and I’ll never stop. Dressing my body.

Martin: What is different about how you think of that?

Slate: I’m pleased to say that I’ve come through a fair amount of internalized misogyny. So 10 years ago I was 31 and it was like, “You better wear that bikini.” You know, just these horrible, brutal feelings about my physical body and about how I needed to present what sexiness was and how much of my body to show.

I’ve always had a pretty clear sense of what I find to be beautiful. But I feel like it was sort of muddled up, and now I just want to dress like Jane Goodall, but like sometimes with a crop top. Like, let it flow.

I used to feel that I had to prove that my butt was there. And now I’m like, it’s not relevant whether or not you think my butt is there. I know it’s there. My toilet knows it’s there. And my husband knows it’s there. And, unfortunately, some of my friends know it’s there.

Question 3: Is there anything in your life that has felt predestined?

Slate: I don’t really connect to the concept of destiny. Sometimes I get scared and ask my husband, “What if we hadn’t met each other? What were the chances?” And he always goes, “100%.” And I like that. I don’t know about the soul mate thing, and I know it sounds so cheesy, but I do feel like he’s my spiritual match.

I guess I believe in a spiritual eventuality, which you could call destiny, but it’s more like a point on the globe. It’s like a fixed point, but it doesn’t mean you’ll get there. You still have to do things to get there. It’s an option.

But no, I’ve never felt like anything was predestined. I’ve just felt as if every now and then there’s a kind of meteor shower and good fortune falls into my life like that.

Martin: Have you always been good about appreciating the meteor shower or has that come later in life for you?

Slate: I think I actually have been. And I think it’s because my mother, who I love dearly, can be rather negative. If you ask her to tell a story, it often sounds as if it were cloudy in the sky, like it’s just with this sort of tinge of dread and negativity. And it’s kind of drama. It’s drama.

My response to that has been to be, no — sunshine! And it can also make me be a terminal optimist in the worst way, like almost a fool. But I think I’ve always had that kind of look out. It’s not a Pollyanna-ish thing. It’s looking for light in the dark. That’s what it is.

To listen to this full conversation, tap play at the top for the Wild Card podcast.

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoLarry Webb’s deathbed confession solves 2000 cold case murder of Susan and Natasha Carter, 10, whose remains were found hours after he died

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoFirst cargo ship passes through new channel since Baltimore bridge collapse

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoHaiti Prime Minister Ariel Henry resigns, transitional council takes power

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoSpanish PM Pedro Sanchez suspends public duties to 'reflect'

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoUS secretly sent long-range ATACMS weapons to Ukraine

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoAmerican Airlines passenger alleges discrimination over use of first-class restroom

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week agoHumane (2024) – Movie Review

-

Education1 week ago

Education1 week agoVideo: Johnson Condemns Pro-Palestinian Protests at Columbia University