Health

What I Saw When I Looked Inside My Own Body

From my CT scan, I expected a brush with mortality — the opportunity to see the forbidden land of my own guts, to contemplate their eventual decomposition. By that point I had already had an organ removed (my gallbladder), and I suppose I expected to register its absence somehow. What I saw instead was just shades of gray and blobs of darkness. Nothing was recognizable as an organ. At one point, I remember, the doctor directed me to pay attention to something that, in his own words, did not look like anything at all. That, he wanted me to know, was my pancreas. He was right: It did not look like anything at all. If, for Anna Röntgen and Hans Castorp, the X-ray produced something that was undeniably and terrifyingly their own body, I was having the opposite experience. Whose body was this? Was it a body at all? Without the doctor there to tell me what it was I saw, I would never have known.

In popular culture, medical imaging represents a simple statement of fact, a question resolving into certainty. Watch episodes of the medical drama “House, M.D.,” and you will see imaging confidently used to diagnose psychopathy, to tell whether somebody is lying, even to visualize the subconscious. People lie and bodies deceive, but tests and scans do not. And so, in the real world, one submits to these devices nervously, as one would to some kind of truth serum or all-seeing eye: There is no hiding here.

Even when we imagine a superhero with X-ray vision, we imagine somebody who sees through the inessential to the essential. In a scene in the 1978 “Superman,” the Man of Steel flirts with Lois Lane first by scolding her for smoking, then by scanning her for lung cancer. (Her lungs glow pinkly and cutely for a moment before he informs her that she’s all clear. Later, at her request, he tells her the color of her underwear.) Like his superstrength, Superman’s X-ray vision is allied to his virtuous nature: His eyes tell the truth and can’t be fooled.

Nobody expects strict medical accuracy from superhero movies. But popular science narratives are hardly more cautious. We are often breathlessly informed, for instance, that parts of the brain “light up” when presented with certain stimuli, telling us precisely what people are thinking and feeling and why. (Of course, parts of the brain do not light up at all — only their images on an f.M.R.I., indicating blood flow.) Even in everyday life, medical images convey an official certainty that’s hard to obtain through other means. I’ve known friends to forgo different parts of the medical process throughout pregnancies, but the pregnancy-announcing sonogram is de rigueur. Without that image to show friends, you simply aren’t pregnant, socially speaking; you just might be.

For medical professionals, though, all these imaging techniques are imperfect tools, just another way to get a partial idea of what might be happening inside a human body. You have to be trained to read them at all. The doctors on “House” run and pore over scans themselves, but in reality both creating and interpreting CT scans are specialized jobs. Radiology can be subjective — not as subjective as, say, art criticism, but not cut and dried. In the future, artificial intelligence may take a greater role in interpreting results — but it will not make the experience any less alienating if, instead of depending on human expertise to analyze your body, a computer program is making judgments and flagging risks based on patterns and correlations even the doctors may not be able to see.

Health

‘The Pitt’ Captures the Real Overcrowding Crisis in Emergency Rooms

The emergency department waiting room was jammed, as it always is, with patients sitting for hours, closely packed on hard metal chairs. Only those with conditions so dire they needed immediate care — like a heart attack — got seen immediately.

One man had had enough. He pounded on the glass window in front of the receptionist before storming out. As he left, he assaulted a nurse taking a smoking break. “Hard at work?” he called, as he strode off.

No, the event was not real, but it was art resembling life on “The Pitt,” the Max series that will stream its season finale on Thursday. The show takes place in a fictional Pittsburgh hospital’s emergency room. But the underlying theme — appalling overcrowding — is universal in this country. And it is not easy to fix.

“EDs are gridlocked and overwhelmed,” the American College of Emergency Physicians reported in 2023, referring to emergency departments.

“The system is at the breaking point,” said Dr. Benjamin S. Abella, chair of the department of emergency medicine at Mount Sinai’s Icahn School of Medicine in New York.

“The Pitt” follows emergency room doctors, nurses, medical students, janitors and staff hour by hour over a single day as they deal with all manner of medical issues, ranging from a child who drowned helping her little sister get out of a swimming pool to a patient with a spider in her ear. There were heart attacks and strokes, overdoses, a patient with severe burns, an influencer poisoned by heavy metals in a skin cream.

Because this is television, many of the thorny problems get neatly resolved in the show’s 15 episodes. A woman who seems to have abandoned her elderly mother returns, apologizing because she fell asleep. Parents whose son died from an accidental fentanyl overdose come around to donating his organs. A pregnant teenager and her mother, at odds over a medical abortion, come to a resolution following a wise doctor’s counsel.

But over and over again, the image is of a system working way beyond its capacity. There is the jammed waiting room and the “boarders” — patients parked in emergency rooms or hallways for days or longer because there are no hospital beds. (The American College of Emergency Physicians calls boarding a “national public health crisis.”)

There are the long waits for simple tests. There is the hallway medicine — patients who see a doctor in the hallway, not in a private area, because there is no place else to put them.

And there is the violence, verbal and physical, from patients with mental problems and those, like the man who punched the nurse, who just get fed up.

“‘The Pitt’ shows the duress the system is under,” Dr. Abella said. “Across the country we see this day in and day out.”

But why can’t this problem be fixed?

Because there’s no simple solution, said Dr. Ezekiel J. Emanuel, co-director of the Health Transformation Institute at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine. The problem, he said is “multipronged and there is no magic wand.”

Part of it is money.

Having patients jammed up in emergency rooms guarantees that no bed will go unused, bolstering revenues for hospitals.

Then there’s the problem of discharging patients. Spaces are scarce in nursing homes and rehabilitation centers, so patients ready to leave the hospital often are stuck waiting for a space to open up elsewhere.

Schedules are another difficulty, said Dr. Jeremy S. Faust, attending physician in the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Department of Emergency Medicine. Many rehabilitation centers admit patients only during business hours, he said. If an E.R. patient is ready to be discharged to one during a weekend, that patient has to wait.

In “The Pitt,” as in real life, patients often show up in emergency rooms with problems — like a child with an earache — that a private doctor should be able to handle. Why don’t they just go to their own doctor instead of waiting hours to be seen?

One reason, Dr. Emanuel said, is that “primary care is going to hell in a handbasket.”

In many cities finding a primary care doctor is difficult. And even if you have one, getting an appointment can take days or weeks.

Many do not want to wait.

“The modern mentality, for better or worse, is: If I can’t get it now, I will look for other solutions,” Dr. Abella said.

That often means the emergency room.

Even building larger emergency rooms has not helped with the overcrowding.

Dr. Faust said that his hospital opened a new emergency room a few years ago with a large increase in the number of beds. A colleague, giving him a tour, proudly told him there was now so much space there would probably be no more hallway patients.

“I looked at him and said, ‘Bwhahahahaha,’” Dr. Faust said. “If you build it, they will come.”

He was right.

Health

Invasive strep throat strain has more than doubled in US, reports CDC

Cases of an invasive strain of strep throat have been steadily rising in some areas of the U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The surveillance study, which was published in JAMA, showed that the incidence of group A Streptococcus (GAS) infection “substantially increased” from 2013 to 2022.

Affected states include California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Maryland, Minnesota, New Mexico, New York, Oregon and Tennessee.

STREP THROAT INFECTIONS HAVE SPIKED ABOVE PRE-COVID HIGHS, SAYS REPORT: ‘WE’VE MISSED CASES’

The overall incidence more than doubled, going from 3.6 to 8.2 cases per 100,000 persons at that time, according to the findings.

For the past near-decade, cases of group A Streptococcus (GAS) have been on the rise in 10 U.S. states. (iStock)

Infection rates were higher among residents of long-term care facilities, the homeless population and injection drug users.

While incidence was highest among people 65 and older, the relative increase over time was biggest among adults aged 18 to 64.

“Accelerated efforts to prevent and control GAS are needed, especially among groups at highest risk of infection,” the CDC researchers concluded in the study.

NOROVIRUS SICKENS OVER 200 CRUISE SHIP PASSENGERS ON MONTH-LONG VOYAGE

According to a CIDRAP press release by the University of Minnesota, GAS is most known for causing non-invasive diseases like strep throat and impetigo.

The strain can also cause more severe infections, like sepsis, necrotizing fasciitis and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome.

GAS can lead to more severe infections, like sepsis and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. (iStock)

The researchers identified 21,213 cases of invasive GAS, leading to 20,247 hospitalizations and 1,981 deaths.

Bacteremic cellulitis was the most common disease caused by GAS, according to the press release, followed by septic shock, pneumonia and bacteria in the bloodstream without an apparent cause (known as bacteremia without focus).

“The recent assault of viruses, including COVID-19, has weakened people’s immune systems.”

In an accompanying JAMA editorial, Joshua Osowicki, MBBS, PhD, a pediatric infectious diseases physician at Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne, said there has been a global uptick in GAS cases following the COVID-19 pandemic.

“In any of its forms — from skin and soft tissue infections, pneumonia, bone and joint infections, or sepsis without a clear clinical focus — invasive GAS can be insidious and unpredictable, testing the lifesaving capacity of even the world’s most advanced medical facilities,” he wrote.

“We really need a vaccine against this, but don’t have it,” Dr. Marc Siegel shared. (iStock)

“Surges of invasive and noninvasive GAS disease in 2022 and 2023 have been reported in countries spanning the Northern and Southern Hemispheres, with new reports of the same phenomenon still coming to light.”

Fox News senior medical analyst Dr. Marc Siegel commented that GAS requires early intervention, as it can be “quite life-threatening” and “misperceived” as something milder.

MEASLES OUTBREAK CONTINUES: SEE WHICH STATES HAVE REPORTED CASES

“We really need a vaccine against this, but don’t have it,” he told Fox News Digital.

“[It’s] increasing dramatically among socioeconomically disadvantaged groups, including the homeless, substance abusers, those with increased skin breakdown and those sharing needles.”

The infection is also associated with IV fentanyl use as part of the opioid epidemic, Siegel added.

After a dip in cases during the coronavirus pandemic, the rate of infections was 30% higher than the previous peak seen in February 2017. (iStock)

In 2023, strep throat infections caused by GAS skyrocketed, mostly in children, according to a report from Epic Research.

After a dip in cases during the coronavirus pandemic, the rate of infections was 30% higher than the previous peak seen in February 2017, the report found.

Dr. Shana Johnson, a physical medicine and rehabilitation physician in Scottsdale, Arizona, previously shared with Fox News Digital that rates of GAS, including the more dangerous invasive type, were “at the highest levels seen in years.”

In an interview with Fox News Digital at the time, Siegel reported that the spike in cases is likely a result of other circulating viruses.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR OUR HEALTH NEWSLETTER

“The recent assault of viruses, including COVID-19, has weakened people’s immune systems,” he said. “Also, we haven’t been on the lookout for them and have missed cases.”

Group A strep is best treated with antibiotics unless a more severe illness is contracted, according to Johnson.

“Antibiotics for strep throat reduce how long you are sick and prevent the infection from getting more severe and spreading to other parts of the body,” she said.

Group A strep cases in 2023 were most identified in kids aged 4 to 13. (iStock)

Group A strep bacteria commonly spread through droplets when an infected person coughs, sneezes or talks, according to the CDC, but can spread through infected sores on the skin.

To help reduce the spread, doctors say to wash hands often with soap and water, avoid sharing glasses or utensils with those who are infected, and cover the mouth and nose when coughing or sneezing.

For more Health articles, visit foxnews.com/health

“If you have strep throat, stay home until you no longer have a fever and have taken antibiotics for at least 24 hours,” Johnson advised.

Fox News Digital reached out to the CDC for comment.

Health

RFK Jr. Offers Qualified Support for Measles Vaccination

In a rare sit-down interview with CBS News, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the nation’s health secretary, recommended the measles vaccine and said he was “not familiar” with sweeping cuts to state and local public health programs.

The conversation was taped shortly after his visit to West Texas, where he attended the funeral of an 8-year-old girl who died after contracting measles. A raging outbreak there has sickened more than 500 people and killed two young children.

In clips of the discussion released Wednesday, Mr. Kennedy offered one of his strongest endorsements yet of the measles vaccine. “People should get the measles vaccine, but the government should not be mandating those,” he said.

A few moments later, however, he raised safety concerns about the shot, as he has previously: “We don’t know the risks of many of these products because they’re not safety tested,” he said.

For months, Mr. Kennedy has faced intense criticism for his handling of the West Texas outbreak from medical experts who believe that his failure to offer a full-throated endorsement of immunization has hampered efforts to contain the virus.

Moreover, he has promoted unproven treatments for measles, like cod liver oil. Doctors in Texas believe its use is tied to signs of liver toxicity in some children arriving in local hospitals.

Throughout the outbreak, Mr. Kennedy has often paired support for vaccines with discussions of safety concerns about the shots, along with “miraculous” alternative treatments.

Over the weekend, he posted on social media that the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine was “the most effective way” to prevent the spread of measles — a statement met with relief from infectious disease experts and with fury from his vaccine-hesitant base.

That night, he posted again, this time applauding “two extraordinary healers” who he claimed had effectively treated roughly 300 measles-stricken children with budesonide, a steroid, and clarithromycin, an antibiotic.

Scientists say there are no cures for a measles infection, and that claiming otherwise undermines the importance of a vaccination.

Later in the CBS interview, Mr. Kennedy was pressed on the administration’s recent move to halt more than $12 billion in federal grants to state programs that address infectious disease, mental health and childhood vaccinations, among other efforts.

(A judge has temporarily blocked the cuts after a coalition of states sued the Trump administration.)

Mr. Kennedy said he wasn’t familiar with the interruptions, then asserted that they were “mainly D.E.I. cuts,” referring to diversity, equity and inclusion programs that have been targeted by the Trump administration.

Dr. Jonathan LaPook, CBS’s medical correspondent, asked about specific research cuts at universities, including a $750,000 grant to researchers at the University of Michigan to study adolescent diabetes.

“I didn’t know that, and that’s something that we’ll look at,” Mr. Kennedy said. “There’s a number of studies that were cut that came to our attention and that did not deserve to be cut, and we reinstated them.”

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoThe FAA hiding private jet details might not stop celebrity jet trackers

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoSupreme Court Rules Against Makers of Flavored Vapes Popular With Teens

-

News1 week ago

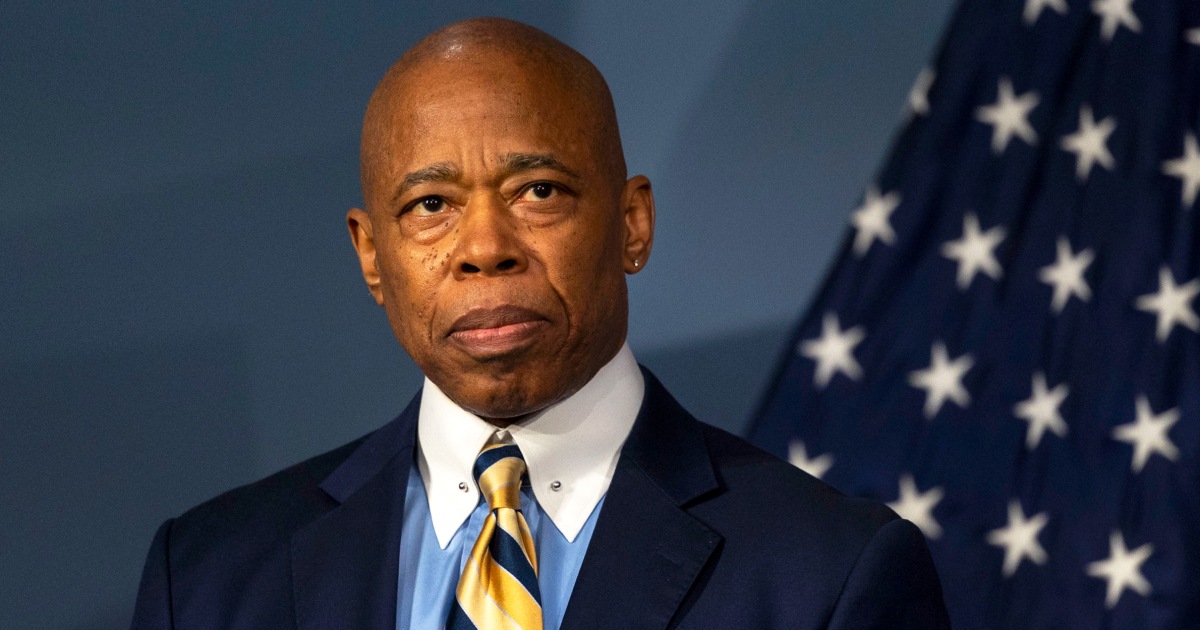

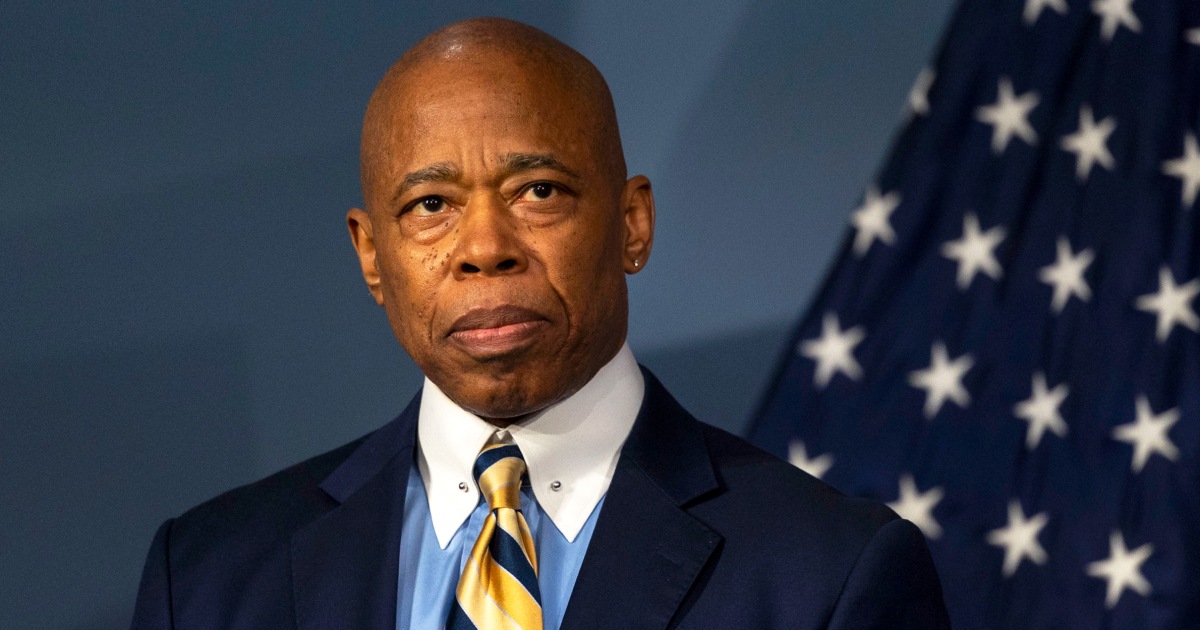

News1 week agoNYC Mayor Eric Adams' corruption case is dismissed

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoHere’s how you can preorder the Nintendo Switch 2 (or try to)

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoWill European agriculture convert to new genomic techniques?

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoTrump to Pick Ohio Solicitor General, T. Elliot Gaiser, for Justice Dept. Legal Post

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoTrump’s ‘Liberation Day’ Tariffs Are Coming, but at a Cost to U.S. Alliances

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoFBI flooded with record number of new agent applications in Kash Patel's first month leading bureau