Health

History Isn’t Entirely Repeating Itself in Covid’s Aftermath

Five years after Covid-19 shut down activities all over the world, medical historians sometimes struggle to place the pandemic in context.

What, they are asking, should this ongoing viral threat be compared with?

Is Covid like the 1918 flu, terrifying when it was raging but soon relegated to the status of a long-ago nightmare?

Is it like polio, vanquished but leaving in its wake an injured but mostly unseen group of people who suffer long-term health consequences?

Or is it unique in the way it has spawned a widespread rejection of public health advice and science itself, attitudes that some fear may come to haunt the nation when the next major illness arises?

Some historians say it is all of the above, which makes Covid stand out in the annals of pandemics.

In many ways, historians say, the Covid pandemic — which the World Health Organization declared on March 11, 2020 — reminds them of the 1918 flu. Both were terrifying, killing substantial percentages of the population, unlike, say, polio or Ebola or H.I.V., terrible as those illnesses were.

The 1918 flu killed 675,000 people out of a U.S. population of 103 million, or 65 out of every 10,000. Covid has so far killed about 1,135,000 Americans out of a population of 331.5 million, or 34 out of every 10,000.

Both pandemics dominated the news every day while they raged. And both were relegated to the back of most people’s minds as the numbers of infections and deaths fell.

J. Alexander Navarro, a medical historian at the University of Michigan, said that in the fall of 1918, when the nation was in the throes of the deadliest wave of the 1918 flu, “newspapers were chock-full of stories about influenza, detailing daily case tallies, death tolls, edicts and recommendations issued by officials.”

During the next year, the virus receded. And so did the nation’s attention.

There were no memorials for flu victims, no annual days of remembrance.

“The nation simply moved on,” Dr. Navarro said.

Much the same thing happened with Covid, historians say, although it took longer for the virus’s harshest effects to recede.

Most people live as though the threat is gone, with deaths a tiny fraction of what they once were.

In the week of Feb. 15, 273 Americans died of Covid. In the last week of 2021, 10,476 Americans died from Covid.

Interest in the Covid vaccine has plummeted, too. Now just “a measly 23 percent of adults” have gotten the updated vaccine, Dr. Navarro noted.

Remnants of Covid remain — lasting financial effects, lags in educational achievement, casual dress, Zoom meetings, a desire to work from home. But few think of Covid as they go about their daily lives.

Dora Vargha, a medical historian at the University of Exeter, noted that there had been no ongoing widespread effort to memorialize Covid deaths. Instead, with Covid, “people disappeared into hospitals and never came out.”

Now it is only their friends and families who remember.

Dr. Vargha called that response understandable. People, she said, do not want to be “dragged back” into memories of those Covid years.

But some, like those suffering from long Covid, can’t forget. In that sense, she sees parallels with other pandemics that, unlike the 1918 flu, left a swath of people who were permanently affected.

People who contracted paralytic polio in the 1950s described themselves to Dr. Vargha as “the dinosaurs,” reminders of the time before the vaccine, when the virus was killing or paralyzing children.

Every pandemic has its dinosaurs, she said. They are the Zika babies living with microcephaly. They are the people, often at the margins of society, who develop AIDS.They are the people who contract tuberculosis.

But despite the pleas from those who cannot forget Covid and who seek more research, more empathy, more attention, the more pervasive attitude is, “We don’t need to care anymore,” said Mary Fissell, a historian at Johns Hopkins University.

That sounds so callous, and yet, said Dr. Barron Lerner, a historian at NYU Langone Health, in the world of public health “there are always people who are left behind — damaged or still at risk.”

“It’s hurtful” for people to be shunted aside, Dr. Lerner said. “Their lives are altered. The attention you feel their situation warrants is downplayed.”

But, he added, “on a realistic basis, there are any number of things to study.” Resources are limited, he noted, adding, “it can make sense to move on.”

One aspect of the Covid pandemic, though, is still with the nation, and seems to be part of a new reality: It has markedly changed attitudes toward public health.

Kyle Harper, a historian at the University of Oklahoma, said he would give the biomedical response to Covid an A-plus. “The rollout of vaccines was incredible,” he said.

But, he said, “I would give the social response a C-minus.”

Dr. Lerner had the same thought.

Few medical experts, he said, expected so much resistance to measures like masks, quarantines, social distancing and — when they became available — vaccines and vaccine mandates.

With Covid, he said, “compared to other pandemics, the amount of pushback to standard public health practices was remarkable.”

“That sets Covid apart,” he said. Public health measures that had worked in the past were rejected.

Some of the pushback was reasonable, he said, like objections to wearing masks outdoors. But the spurning of public health measures was widespread and politicized.

Dr. Navarro agreed and said the contrast with 1918 was striking.

“In 1918, there was an abiding respect for science and medicine that seems lacking today,” he said. There were pockets of resistance to measures like masking and avoiding large groups. But for the most part, he said, people complied with public health advice. And compliance was divorced from politics.

World War I also played a role in the messaging, Dr. Navarro said, which may have bolstered adherence.

“Public health orders and recommendations often purposely used the same language that was used to drum up support for the war effort,” Dr. Navarro said. The authorities, for example, asked people “to cover their coughs and sneezes so as not to gas their fellow citizens as the doughboys were being gassed by the Germans.”

Dr. Lerner contrasted the Covid response to the response to the polio vaccine.

The polio vaccine underwent preliminary testing, and then widespread testing, in the 1950s, with broad public acceptance.

With Covid, “faith in the scientific process got lost,” Dr. Lerner said.

That does not bode well for the next pandemic, Dr. Harper said.

“There’s going to be another pandemic,” he said. “And if we have to fight it without public trust, that’s the worst possible response.”

Health

New GLP-1 Called MariTide Shows 20% Weight Loss—Without a Plateau

Use left and right arrow keys to navigate between menu items.

Use escape to exit the menu.

Sign Up

Create a free account to access exclusive content, play games, solve puzzles, test your pop-culture knowledge and receive special offers.

Already have an account? Login

Health

Never smoked? You could still be at risk of developing lung cancer, doctors warn

NEWYou can now listen to Fox News articles!

Lung cancer, the second-most common cancer in the U.S., is often associated with smoking — but even those who have never had a cigarette could be at risk of the deadly disease.

While it’s true that those who smoke face a much higher risk, up to 20% of lung cancers affect people who have never smoked or have smoked fewer than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Despite this, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) does not recommend lung cancer screening for those who have never smoked, as the agency states the risks may outweigh the potential benefits.

DISPOSABLE VAPES MORE TOXIC AND CARCINOGENIC THAN CIGARETTES, STUDY SHOWS

Most lung cancers fall into two groups: non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and small cell lung cancer (SCLC), according to the American Cancer Society.

NSCLC, which encompasses about 80% to 85% of all lung cancers, includes adenocarcinoma (common in non-smokers), squamous cell carcinoma and large cell carcinoma.

Up to 20% of lung cancers affect people who have never smoked or have smoked fewer than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime. (iStock)

The remaining lung cancers are classified as SCLC, a more aggressive type that tends to spread faster and has a poorer prognosis.

Mohamed Abazeed, M.D., Ph.D., chair of radiation oncology and the William N. Brand Professor at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, agrees that the share of lung cancers diagnosed in never-smokers is increasing, particularly among women and patients of Asian ancestry.

CANCER DEATH RATES DECLINE YET NEW DIAGNOSES SPIKE FOR SOME GROUPS, SAYS REPORT

“While overall incidence is declining due to reduced smoking rates, the relative share of never-smokers is growing and is reflected in clinical practice, where we increasingly diagnose patients without a traditional smoking history,” he told Fox News Digital.

Dr. Lauren Nicola, a practicing radiologist and chief medical officer at Reveal Dx in North Carolina, said she is also seeing an increase in the rate of newly diagnosed lung cancer in non-smokers, particularly among women and younger adults.

Most lung cancers fall into two groups: non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and small cell lung cancer (SCLC), according to the American Cancer Society. (iStock)

The main factor driving up the share of non-smokers among lung cancer patients, according to Abazeed, is the successful drive to reduce tobacco consumption in the U.S.

“Other factors include improvements in imaging and broader use of CT scans that have enhanced early-stage tumor detection,” he noted.

“It is estimated that about 8% of lung cancers are inherited or occur because of a genetic predisposition.”

“Evolving environmental factors may also be contributing to this change, with pollutants potentially driving lung inflammation, which in turn has been implicated in cancer development.”

Modifiable risk factors

Some of the biggest non-smoking risk factors for lung cancer include ambient air pollution and secondhand smoke, according to Abazeed.

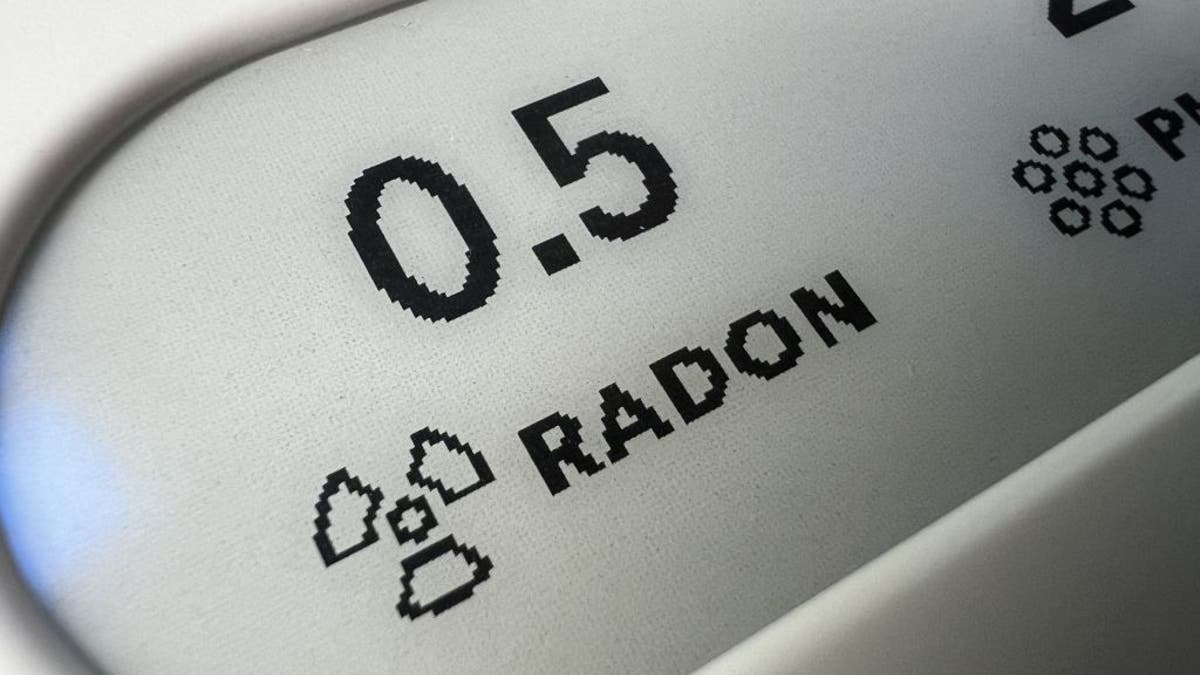

Exposure to thoracic radiation (high-energy radiation in the chest area) — along with occupational hazards like radon, asbestos and diesel exhaust — can also increase the risk.

The main factor driving up the share of non-smokers among lung cancer patients is the successful drive to reduce tobacco consumption in the U.S., experts say. (iStock)

Lifestyle-related inflammation, which is often linked to poor diet and sedentary behavior, can also play a role, Nicola noted.

“Some of these, like radon and air quality, can be addressed at the household or policy level,” Abazeed said.

RISKS, SYMPTOMS AND TREATMENTS FOR LUNG CANCER, THE DEADLIEST CANCER IN THE WORLD

“Lifestyle interventions — such as exercise, diet and avoidance of indoor pollutants — may play a modest protective role.”

Both doctors pointed out that former smokers, especially those who smoked more often and for longer periods of time, remain at elevated risk even decades after quitting.

“The greater the number of pack-years, the higher the risk,” said Nicola. “Risk declines over time after quitting, but never returns to the baseline of a never-smoker.”

Genetic risk factors

Some people inherit a higher risk of developing lung cancer due to their DNA.

“It is estimated that about 8% of lung cancers are inherited or occur because of a genetic predisposition,” Abazeed told Fox News Digital.

“Inherited predisposition is an area of active investigation, particularly in younger patients or those with a strong family history.”

Having a first-degree relative with lung cancer roughly doubles the risk of developing the disease, even after controlling for smoking exposure, according to Nicola.

“Up to 50% of all chest CTs will detect at least one pulmonary nodule.”

“Cancers in non-smokers are more often associated with specific genetic mutations and genomic profiles,” she said. “This suggests that these malignancies have a different underlying biology compared to tumors in smokers.”

Screenings in question

Current U.S. screening guidelines call for annual low-dose CT scans for high-risk individuals based on age and smoking history, Abazeed reiterated.

The USPSTF recommends screening for “adults aged 50 to 80 years who have a 20 pack-year smoking history and currently smoke or have quit within the past 15 years.”

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR OUR HEALTH NEWSLETTER

“There is a growing interest in expanding eligibility to include non-smoking risk factors,” Abazeed noted. “Evidence is accumulating that could potentially change current population-wide guidelines.”

There are some potential risks linked to expanding screening, experts say, including the potential for overdiagnosis and false positives.

Exposure to occupational hazards like radon, asbestos and diesel exhaust can increase lung cancer risk. (Photo by Gado/Getty Images)

“The problem with screening everyone for lung cancer is that up to 50% of all chest CTs will detect at least one pulmonary nodule,” Nicola noted. “The vast majority of these nodules are benign, but a small percentage will turn out to be cancer.”

Based primarily on the size of the nodule, the clinician may recommend follow-up imaging or biopsy.

For more Health articles, visit www.foxnews.com/health

“New tools are being developed that can help us better characterize the malignancy risk of a nodule, which will decrease the potential for harm associated with overdiagnosis in screening,” Nicola said.

Health

How Cutting ‘Truck-Stop Foods’ + Alcohol Help Tim McGraw Lose 40 Pounds

Use left and right arrow keys to navigate between menu items.

Use escape to exit the menu.

Sign Up

Create a free account to access exclusive content, play games, solve puzzles, test your pop-culture knowledge and receive special offers.

Already have an account? Login

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoSchumer to force Senate reading of Trump's entire 'big, beautiful bill'

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoNew L.A. Trader Joe's opens across the street from … another Trader Joe's

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week ago5.4 million patient records exposed in healthcare data breach

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoCommissioner and MEPs in Budapest to challenge Orban’s Pride ban

-

Technology1 week ago

Technology1 week agoTesla says it delivered its first car autonomously from factory to customer

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTrump administration takes on new battle shutting down initial Iran strike assessments

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoUganda’s President Museveni confirms bid to extend nearly 40-year rule

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoUS multinationals on track for minimum tax reprieve after G7 deal