The opening of Bottle Radha is an overhead shot of Chennai, with a speaker somewhere playing ‘Thanni Thotti’ from Sindhu Bhairavi (it’s a staple booze anthem in Tamil). There are over a dozen shots of alcohol being poured into glasses in this film, and of men downing bottle after bottle to the point you wonder how they are even alive. Towards the end, there is a bar song with men dancing ecstatically. But before you jump to conclusions, this isn’t the film that celebrates alcoholism.

Debutant director Dhinakaran Sivalingam’s film is a two-hour drama that persistently focuses on the prevalent issue of alcohol addiction. That bar song I mentioned? It’s an intriguing tactic to send a dark message, in a medium that has often used such songs to celebrate boozing.

Radhamani a.k.a Sorakkapalyam Radha (Guru Somasundaram) is a middle-aged man who spends much of his time and money in the liquor shop, chugging bottles and engaging in petty quarrels. He is a deadbeat with no redeeming qualities, and Sivalingam holds no bars in depicting the flaws of his protagonist. Radha appears drunk even at his work site, and his job as a construction worker is an irony by itself. He knows nothing about building a home — the one you build with affection, responsibility, a longing for peace and comfort, and a million other little things — but claims to be an expert in building houses — empty structures made with bricks, cement and sand that are brought to life by families. That he builds houses for other families while squandering the future of his wife Anjalam (a fantastic Sanchana Natarajan) and their two kids says a subtle something about who alcoholism more often ends up affecting, and the whys and hows of its prevalence among the working-class (in umpteen instances, the film humorously points out how many addicts refuse to take responsibility because “it’s the government that has a liquor shop every corner,” but it also shows what easy accessibility can do to addicts in recovery).

In an unexpected turn for Radha, his wife, tired of making this ill-behaved man see some sense, forcibly enrols him in a one-of-a-kind de-addiction centre. In a dilapidated room are lodged dozens of addiction patients. Much of these initial portions are treated with humour, and many scenes featuring Lollu Sabha Maaran leave you in splits. However, this de-addiction centre is where issues with Bottle Radha also begin. Firstly, many of the characters we see in this de-addiction centre add nothing to our understanding of how these places function, or what goes in the mind of an addict.

Bottle Radha (Tamil)

Director: Dhinakaran Sivalingam

Cast: Guru Somasundaram, Sanchana Natarajan, John Vijay, Lollu Sabha Maaran

Runtime: 146 minutes

Storyline: An alcoholic gets stuck in a vortex that sucks all happiness from his life, and ends up seeking help at a de-addiction centre

Ashokan (John Vijay) runs the place with a firm, fair hand — he minces no words when the patients justify their acts and reprimands his subordinate Elango, a strange man with a compulsion for cruelty. But except for a patient’s passing remark on the centre’s budget, we are never told what Ashokan feels about the concerning state of this strange place. As much as they help the film’s humour, the patients add little value to Radha’s story. Also, what was the point of that romance between two mentors that goes nowhere? Sure, Elango’s case, and the sorry state of his victims, paint a stark picture of how these centres function, but what good does it do when we don’t understand what goes behind Elango’s hunger for power? You also wonder if Elango’s violence towards a patient had to be so excessive. Similar is the case with a scene in which The Shawshank Redemption is played at the centre; though you are impressed by this fresh take on a timeless classic, you are left with a sense of unease in how the sequence ends.

Bottle Radha chooses heart over intellect, relying solely on drama to do all the heavy lifting, and ends up offering scattered returns. In one of the hard-hitting stretches, Radha is consumed by darkness, anything resembling light devoured by his almost life-threatening addiction. His bloodshot eyes mince all that self-loathing into a contempt for the world, and you almost forget that this is an enactment. No slight emotions escape Guru Somasundaram’s face, and many scenes feature the performer pouring his heart out. Yet, in another scene, when he listens to a man open up on how alcoholism destroyed his family, Somasundaran appears….only as Somasundaram. Make no mistake, the issue isn’t with the actor; in fact, it is he who powers the film to become something more than what it settles to be.

The performance appears as such because the story’s didactic pursuit leads to many contrived situations and scenes. The film is so focused on taking us through the highs and lows of Radha’s alcoholism that it forgets to make him whole. This is disappointing because in a scene he tells Anjalam about how despite starting his days with a lot of resoluteness to not drink, ‘something’ pulls him back to the bottle. This something sometimes is external — like his friend Shake (Pari Elavazhagan) whose idea of a grand death is to die drinking — but except for a detail about his childhood, we don’t get much to understand the internal struggle of Radha. The film repeatedly tells us that every time he feels low, he goes on a bender and that he hasn’t seen all that lies beyond the bottle. But why does he chase the high of alcohol in the first place? Is it after a sense of security? Or, does it come from having grown up without a proper support system? Or maybe a disease is a disease and it can never be understood; maybe it’s a vortex to oblivion, but if that’s the case, why can’t we see, say, Ashokan speak about all that?

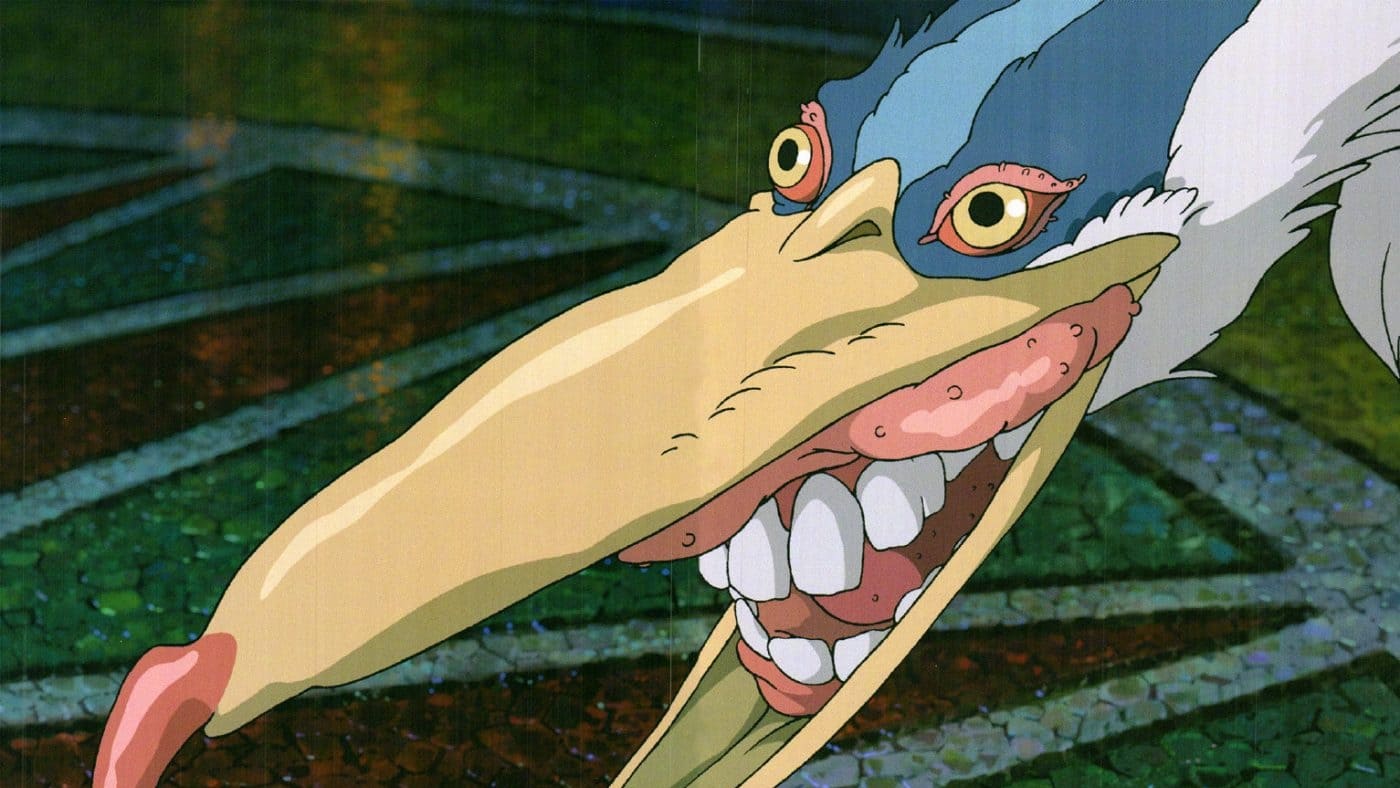

A still from ‘Bottle Radha’

| Photo Credit:

Think Music India/YouTube

ALSO READ:‘Kudumbasthan’ movie review: Manikandan maintains his winning streak with this entertaining comedy caper

Instead, all we get are repetitions of Radha’s drinking, relapses and otherwise, and after a point, you hardly care about what lies ahead of him. Fascinatingly, you are more drawn towards the story of Anjalam and how she deals with this precarious marriage. Her arc wonderfully underlines how alcoholism, like most other social crises, affects women from poorer sections of society. In one of the initial scenes, a police officer warns Anjalam of punishment, pinning responsibility on her for how her husband behaves; in another heartbreaking scene with splendid performances, she heartbrokenly confesses all that she endured in the absence of her deadbeat husband. How her arc shapes up might be a tad too predictable, but what she stands for compels you to look beyond the flaws in the film.

The flaws, however, don’t diminish the importance of a film like Bottle Radha. And for a feature debutant, this is a commendable start by Sivalingam. As in a beautiful scene between Anjalam and Radha in the rain, many moments hint at a filmmaker with a lot of heart and ambition.

Bottle Radha is currently running in theatres

Published – January 25, 2025 11:39 am IST

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25835602/Switch_DonkeyKongCountryReturnsHD_scrn_19.png)