Entertainment

John Pisano, dean of L.A. jazz guitar, dies at 93

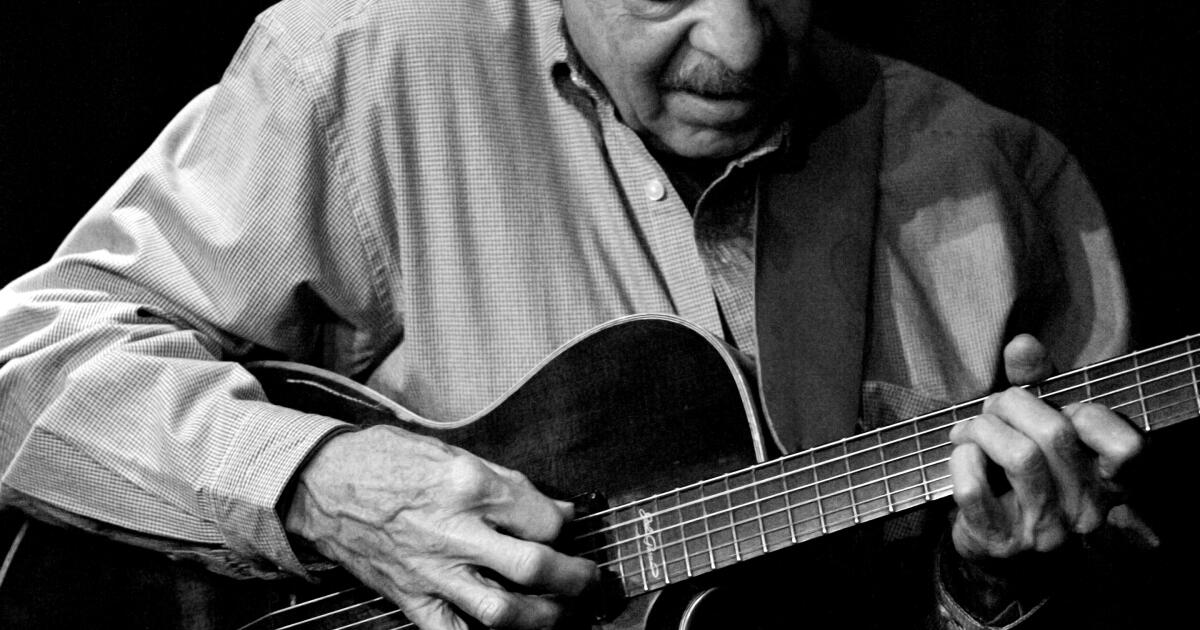

Jazz guitarist extraordinaire John Pisano, renowned for his solid rhythm, melodic solo lines and generosity, died May 2 at his home in Studio City with his wife Jeanne by his side. He was 93 years old.

Pisano’s career spanned seven decades and included sharing the stage or recording studio with many jazz luminaries, including Chico Hamilton, Herb Alpert, Peggy Lee, Frank Sinatra, Benny Goodman, his longtime friend Joe Pass, and nearly every notable guitarist in the business as host for 22 years of his Guitar Night at Spazio Restaurant in Sherman Oaks.

Bob Bakert, editor of Jazz Guitar Today, said, “A finer gentleman I’ve never met. John was a consummate gentleman and a gracious, truly caring guy. It was always about the music and camaraderie and his love for his fellow musicians. John was a master craftsman.” Bakert noted that Pisano’s Guitar Night tradition lives on in distinguished guitarist Frank Vignola’s Guitar Night at Birdland in New York, an intentional tribute to Pisano.

Vignola said, “At the age of 5, one of the first recordings I heard was Joe Pass’ ‘For Django.’ My guitar teacher, Jimmy George, and my father used to tell me to listen to the rhythm guitarist, John. I got to know him and record with him in the early 2000s when I played a rare touring appearance with Les Paul. He had me over to his house, made me a pizza and we recorded all afternoon. What a swinging guitar player. Later, while on tour with Vinny Raniolo, we played Guitar Night.

John Pisano and Chris Conner in 2017.

(Bob Barry / Jazzography)

“This totally inspired me to aspire to having a Guitar Night in New York City. After COVID, Ryan Paternite reached out to me … asking if I would consider a weekly Guitar Night, ‘like John Pisano’s,’ as he put it. I was pleasantly surprised that he knew of John and how awesome his Guitar Night was. I immediately jumped at the opportunity, and we’ve been there almost three years now, every Wednesday night playing to near sold-out crowds weekly.

“What a great personality, person, player, songwriter and pizza maker.”

“John originally began his regular and ongoing (over almost two decades) Guitar Night series as a way to keep his chops in good shape and to stay inspired via encounters with other guitarists,” said Anthony Wilson, a guitarist and composer who is known for a body of work that moves fluidly across genres and is a frequent guest at Guitar Night.

The steady gig quickly became a hub for the guitar community in L.A. and was eventually a required stop for the many noted players who traveled here from around the country as well as from points beyond. Pisano grew very naturally into his role as the dean of this large intergenerational group of guitarists, guitar designers and builders, and guitar enthusiasts, hosting the evenings with a warm, generous spirit, and playing with a wide-open sense of musical curiosity that invited diverse approaches to the instrument and always kept the music vital and absorbing, Wilson remembers.

Pisano was born on Staten Island, N.Y., on Feb. 6, 1931. His first influence musically was his father, Americo Pisano, who played guitar but never professionally, according to John’s online biography. He started learning piano at about the age of 10, but never really cared to practice. It was about 13 when he started playing guitar.

He developed quickly on the instrument, showing as much innate skill as musical understanding. Then he heard Charlie Christian, a pioneer of jazz guitar, and not long after Django Reinhardt, which deepened his love for the guitar. He was also introduced to the jazz radio station WOV in New York and heard Charlie Parker. “Birdland had a live broadcast about 3 or 3:30 in the morning. I remember recording people off the radio like Tadd Dameron and Fats Navarro with an acetate disc recorder that I owned,” he wrote.

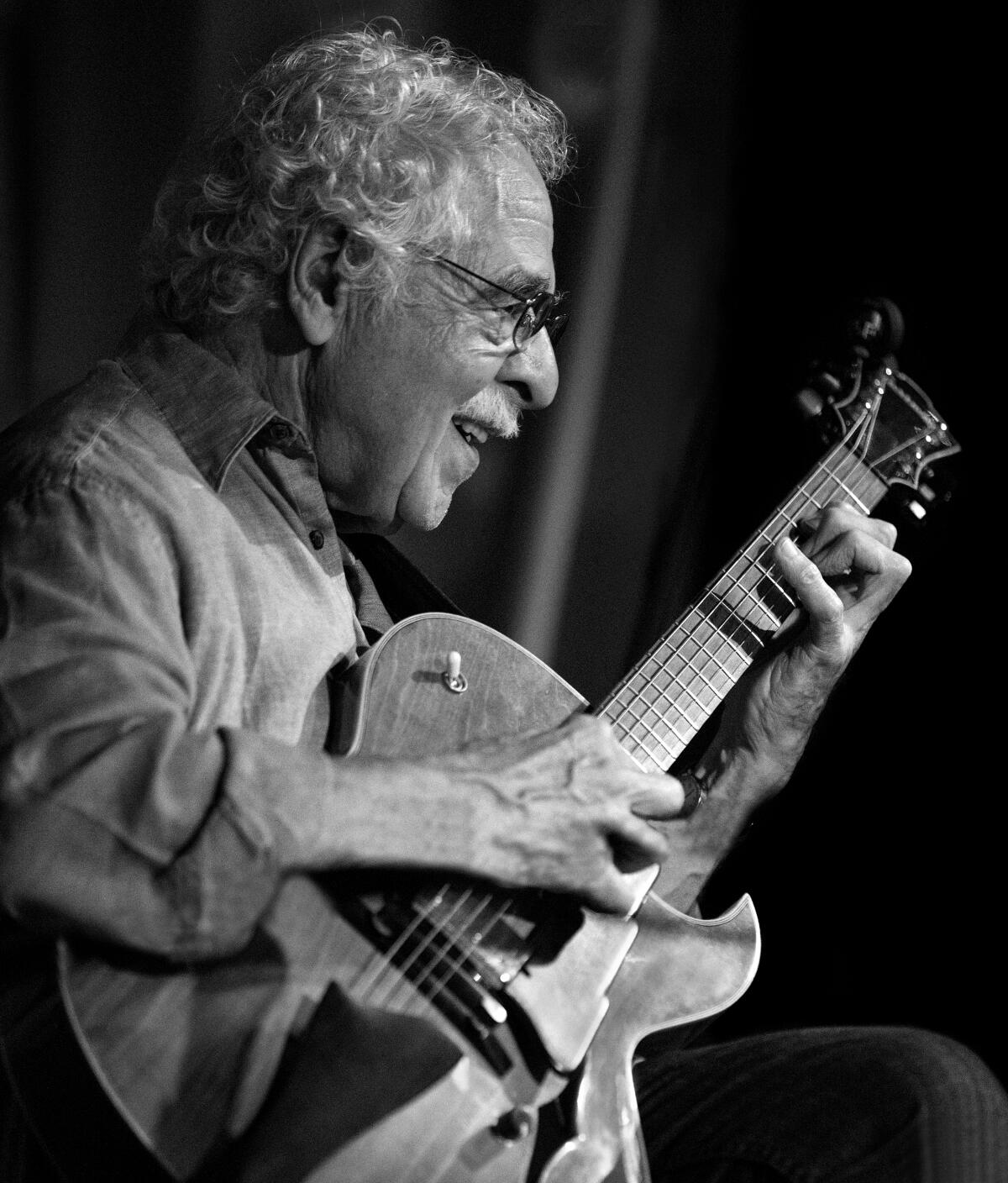

John Pisano in 2013

(Bob Barry / Jazzography)

In 1952, after being in the U.S. Air Force for about eight months, Pisano auditioned for the Air Force Band. It was the only authorization for a guitarist in the Air Force, and he got the gig, which included a lot of recruiting broadcasts.

Pisano said that he never considered himself to be a professional musician until he started playing with the U.S. Air Force band. He was also playing with the Crew Chiefs, an official Air Force group that did some touring, including a 1955 Bob Hope U.S.O. show in Greenland and a spot on “The Steve Allen Show” in Los Angeles.

When he left the service, Pisano was planning to attend the Manhattan School of Music. Shortly before he started his studies, saxophonist and friend Paul Horn, who was then working with the Chico Hamilton band, called to say that Jim Hall was about to leave the band. Horn persuaded Hamilton to audition Pisano, who joined the band and ended up staying in California. Hamilton’s band could be described as a chamber jazz quintet and produced several successful albums, including the music for the film “The Sweet Smell of Success.”

Pisano left the Hamilton band circa 1956 and did some session work while he studied music at Los Angeles City College. In 1958, Pisano recorded two albums of guitar duets with Billy Bean, “Makin’ It,” and “Take Your Pick,” which were both well-received.

Pisano met Pass in 1962, when he asked Pass to fill in for him with Pat Cavanaugh’s band while Pisano went on tour with Peggy Lee. Pass was still at Synanon but he was already something of a legend and very well known throughout guitar and jazz circles. Their first recording together, “For Django,” in 1964, has become a touchstone among jazz guitarists. They went on to record well over a dozen albums together including “Whitestone,” which Pisano co-produced; “Ira, George and Joe” in 1981, on which Pass played a 12-string guitar; and “Duets” in 1991, an album of rich interplay and complex harmonies.

John Pisano, Jim Fox and Dave Stone in 1999.

(Bob Barry / Jazzography)

Always keeping busy, in addition to his session work, Pisano joined Herb Alpert’s Tijuana Brass in 1967. He contributed tunes to the band’s repertoire and recorded with many artists who were on Alpert’s A&M record label. Pisano played on all the early Sergio Mendes hits, and some tunes with Burt Bacharach. During that period, he was always traveling and recording. He was with Alpert’s band for about four years before the band folded.

“John was certainly a father figure to me, both personally and musically, encouraging me and showing me astounding things on the instrument at a crucial point in my development as a musician,” said Wilson, “I relished the many opportunities I had to play with him and learn from him, from casual sessions at home that included his famous homemade pizzas, to many Guitar Nights, recording studios and concert halls.”

Apart from a great teacher, Wilson also describes John as a lifelong student. The two sometimes took lessons together — often joining “life-changing” tandem two-hour sessions with the legendary guitar teacher Ted Greene. Wilson added, “As a duo partner John was truly remarkable, always providing the exact kind of accompaniment needed — the right chord, the right rhythm, the right feel — with a sensitivity that seemed to be a musical reflection of his personality, which was empathetic, encouraging, and nurturing — like the best kind of friend, you always knew John had your back.”

Pisano is survived by his wife, Jeanne, a singer who performed with John as the Flying Pisanos, his son Christopher and daughter Alyssa. The family asks that in lieu of flowers, donations be made in Pisano’s honor to the Los Angeles Jazz Society.

Movie Reviews

Mai Movie Review: Emotionally powerful lead performances in this sensitive and heart-breaking romantic film

A highly skilled professional masseuse, Mai moves into town and joins a spa. No one really knows what she does for a living, but speculation abounds as to her likely source of income. Disrespectful terms like “sugar baby” and “hooker” are thrown at her behind her back while one neighbour accuses her of attempting to steal her husband (the blame being placed on Mai instead of the lecherous spouse in question). When she is not looking, ladies in the adjoining flats litter her doorstep with garbage and dog poop. These civic squabbles and jealousies may be presented in a melodramatic manner but they highlight the struggles of single women living by themselves in South East Asia (and elsewhere). Judgement and a lack of privacy are two issues that are commonly faced. Local playboy Duong and an independent, middle-aged woman are the only people who are accepting of Mai. If her domestic situation wasn’t hard enough, there are co-workers at the massage parlour upset with Mai’s success. She is booked on most days, with her colleagues worried about their regular clients being poached. When male customers wish for special services, she is quick to tell them that she is a professional and to keep any dodgy requests at the door. This attitude further enrages her contemporaries. Meanwhile, Duong, who’s footloose and fancy-free, takes a genuine liking to his neighbour.

Mai isn’t a film that can be easily categorised. Sure, there’s a love story on which everything hinges, but to reduce it to just that would be doing it a huge disservice. Sexual violence and suicidal ideation, complex family dynamics (not on the part of Mai alone but Duong too), deep-seated issues of trust and self-loathing as a direct result of past abuse, the inability of the child to sever ties with the parent, gambling addiction and resultant debt—there is a lot of heavy subject matter to uncoil here. And the intrigue makes each subsequent part of the story fairly unpredictable. You know some bad things are coming, but you’re neither sure of their extent nor their scope. Phuong Anh Dao does a phenomenal job as the film’s lead. Sensitive, kind and understanding, though she keeps those who try to get too close at an arm’s length. Her past is something that has clearly affected her life in an adverse way, and she wishes to steer clear of vulnerability. Even as Duong sheds his playboy persona when he develops feelings, she resists the urge to reciprocate. Shame is another repetitive theme witnessed through the film. It is indeed unfortunate that Mai judges herself so harshly; it is for those who wronged her (including her gambling addict father dependent on her for money) to feel shame. Sadly, that’s not how things work. And despite a supportive daughter, a benevolent benefactor and a man genuinely in love with her, it is hard for her to see her true worth.

Complicated parent-child dynamics are seen through Mai, with it being a difficult subject to shake off. Mai’s relationship with her father is fraught with issues; a role-reversal of sorts can be seen (she has to mother and protect him constantly). For all intents and purposes, he was a terrible father, putting her early life at grave risk. Duong, for his part, lives forever in his wealthy, single mother’s shadow. He stays on his own and dreams of pursuing a career in music, but everything is done on her dime. And not for a moment does she allow him to forget any of the sacrifices made. Worm, his pet name, only reinforces where all the power lies. These two parents, at different ends of the graph, are both equally to blame for their children’s internal struggles.

Beautiful and poignant, it is the sheer emotional range of Phuong Anh Dao and Tuan Tran that holds the film together. What is not said leaves a mark. Their faces and eyes tell a story beyond the dialogue. Mai has this strange ability to surprise you when you finally feel like you’ve called its bluff, and that remains one of the film’s foremost qualities. The writing doesn’t deal with its themes in a flippant manner. It goes to the heart of trauma, where love was once broken (perhaps even irreparably), to see if a small window of trust may yet remain. There are layers to Mai that aren’t easy to decode. The film attempts to understand that undefinable feeling, romantic or otherwise, setting itself apart in the process.

Entertainment

Review: Was the 1964 Venice Biennale rigged? The documentary 'Taking Venice' looks at conspiratorial claims

The Venice Biennale may have lost much of its singular luster, now that hundreds of periodic surveys of new international art have joined the roster of what was the first — and, for decades after its 1895 founding, one of the few — of its kind. An artist can still get an important career boost from successful participation in the venerable and widely publicized Italian exhibition, currently in its 60th outing. (It remains on view at the city’s Giardini and Arsenale through Nov. 24.) But no one anymore expects the extravaganza to dramatically alter larger perceptions of art, the way it once did — perhaps most notably in 1964.

That was the year Robert Rauschenberg, then 38, became the first American artist to win the coveted Grand Prize for Painting, now called the Golden Lion. At the announcement, all hell broke loose. “Treason in Venice,” yelled one newspaper’s overheated headline.

The unprecedented award to an American artist who, a decade earlier, portended the controversial Pop Art genre cresting sealed a slow but steady shift underway since the end of World War II: New York officially bumped Paris from the top slot of cultural taste makers. The critical press in Europe, especially France, framed the story as a scandal. Surely skulduggery was at work.

That’s a frame of reference that guides “Taking Venice,” a bumpy new documentary directed by filmmaker and longtime New York art writer Amei Wallach. “Taking Venice” doesn’t take a position on whether dishonest mischief sullied the jury’s process of choosing Rauschenberg, although it does leave the appropriate sense that the artist easily measured up to the honor. (The other Biennale prizes went to Hungarian-Swiss sculptor Zoltan Kemeny, German draftsman Joseph Fassbender, Italian etcher Angelo Savelli and sculptors Andrea Cascella and Arnaldo Pomodoro — all respectable at best.) Yet, the framing also gets in the way of an otherwise well-informed view of a significant historical moment.

Conspiracy theories drove the original “scandal” story line, but the maneuvering to get the prize was actually business as usual. When something unexpected and dramatic occurs, like the Biennale’s American “first,” the creation of a conspiracy theory is one way to make at least a semblance of sense out of a seemingly inexplicable event. An irrational illusion of rational explanation, it provides a veil of stability in a topsy-turvy world.

Rauschenberg’s anointing was all too much for those who simply could not fathom that Paris — fountainhead of Picasso, Matisse, Miro, Brancusi and even Duchamp — had been toppled on the international cultural stage by a supposedly vulgar, Texas-born parvenu who silkscreened commercial images of President Kennedy and phallic rocket ships onto canvas and famously slathered paint on the nose of a stuffed goat (“Monogram,” 1955-59). A cultural crime had occurred. Guilt needed to be ascribed. Conspiracies mushroomed.

The story of what actually went on in the run-up to the prize is certainly complicated. For clarity, Wallach smartly crafts the film around four primary players, starting of course with “The Artist.” A thumbnail of his artistic bio unfolds.

Then there’s “The Dealer,” Leo Castelli, a suave and affable Italian expatriate to New York who engineered the rise of American Pop, including Rauschenberg, to commercial success. Raised in Trieste, across the Adriatic from Venice, he also understood the European fascination with the democratic capitalism represented by Pop’s soup cans, Hollywood celebrity and comic strips, as postwar rebuilding relied on American commercial goods. That the gallery operated by Ileana Sonnabend, Castelli’s Romanian ex-wife, was located in Paris didn’t hurt.

“The Insider” is Alice Denney, a Washington, D.C., art maven, wife of a State Department lawyer, and friend of the Kennedy family. (Denney died in November at 101.) For the first time, the United States government was helping sponsor the privately operated American Pavilion in Venice, as foreign governments always did theirs. When a boost was needed, like getting a military cargo plane to transport large-scale art across the Atlantic, Denney was on hand to push the necessary buttons.

Finally, “The Commissioner” organizing the American presence at the Biennale was Alan Solomon. He had turned Manhattan’s Jewish Museum into an avant-garde hothouse during his brief tenure as director, from 1962 to 1964, including with solo shows of Rauschenberg and his former lover, Jasper Johns. Solomon, not well-known today, was a Harvard-educated bon vivant known for his erudition in new art’s European history. In 1970, when he died of a heart attack at 49, just a few months after the opening of his last exhibition, “Painting in New York: 1944–1969,” at the Pasadena Art Museum, he was chairman of the adventurous new art department at UC Irvine.

“Taking Venice” re-creates a last-minute move of big Robert Rauschenberg paintings via water taxis to the Giardini.

(Zeitgeist Films)

The artist, the dealer, the insider, the commissioner — the complexities of getting the Venice presentation together are clearly laid out in the film. Appropriate nods are also given to familiar elements of cultural context, which contributed to the ultimate commotion.

The list is long. Rauschenberg’s controversial work had been categorized as Dada-inspired “anti-art.” The sponsoring U.S. government had well-established Cold War propaganda interests. Solomon’s show was too large for the relatively small American Pavilion, so a rules-busting annex was pressed into service in the empty former U.S. consulate next to Peggy Guggenheim’s palazzo-museum on the Grand Canal, adding to a sense of superpower pushiness. International resistance was greeting President Lyndon B. Johnson’s expansion of U.S. military presence in Indochina, which chipped away at global sympathy in the wake of the Kennedy assassination. Sam Hunter, an influential American art historian, was an eleventh-hour addition to the prize jury. At Venice’s legendary Teatro La Fenice, a last-minute all-American avant-garde dance performance by Merce Cunningham and John Cage with sets by Rauschenberg was a wild success. And much more.

Still, all of that was merely packing the dynamite. For an explosion, the fuse needed lighting. It was Solomon who brought the matches.

The Grand Prize selection was always the result of obscure dealings among influential partisans in smoke-filled backrooms, but Solomon drew an aggressive public line in the sand. As the deadlocked jury deliberated privately, he held a press conference and distributed an official statement. Headed “Americans in Venice” — printed all in caps — the sheet featured a tourist photo of the ancient Rialto Bridge spanning the Grand Canal juxtaposed with a three-tiered painting of an American flag by Johns.

In case the pictorial story of crossing a Rubicon was not enough, the blunt text declared, “The fact that the world art center has shifted from Paris to New York is acknowledged on every hand.” Venice’s celebrated Biennale, Solomon implied, risked irrelevance.

Rauschenberg’s ultimate selection certainly gave everyone something to talk about — and they did, often loudly. (The pick sowed “the seeds of a new fascism” in the opinion of one particularly outlandish review.) The artist himself was happy but anxious, soon deciding to destroy all the silk screens he had used to make his exhibited paintings so he couldn’t repeat himself. In retrospect, he observed of the new career pressures, “There were moments when I thought things would have been much better if I hadn’t been so lucky.”

But a conspiracy? Despite the film’s annoying musical score (by CheeWei Tay), which pulses furiously like it’s a B-movie melodrama, that’s nowhere to be found. The horse-trading vote feels more like the norm, which is interesting enough. Thanks to the internet and social media today, conspiracy theories have become epidemic, since the multitudes can now hear the same fantastical whispers of a rigged game en masse. (For details, Google “Jan. 6, 2021.”) Sixty years on, their ubiquity makes “Taking Venice” seem rather quaint.

Much of the story’s factual scaffolding was plainly provided by “The Great Migrator: Robert Rauschenberg and the Global Rise of American Art,” the critically acclaimed 2010 book by art historian Hiroko Ikegami. (She appears in the film to offer welcome narrative detail.) Sometimes the story wanders off into lengthy but unnecessary asides, including staged re-creations of the lightly comic difficulty in moving (faux) Rauschenberg paintings on water taxis, Sonnabend’s dealer adventures in Paris and the American Pavilion shows held in 2017, 2019 and 2022. At 98 minutes, “Taking Venice” is a half-hour too long.

Still, the story embedded within it is an important one. A historic shift did occur. The account is well-told and worth knowing, even without conspiratorial murmurs.

A sneak-peek of the film is scheduled for Thursday at the UCLA Hammer Museum, followed by a Q&A with the director. Wallach will do the same on Friday and Saturday nights at the Laemmle Royal in West L.A., where the film opens for a one-week run.

‘Taking Venice’

Not rated

Running time: 1 hour, 38 minutes

Playing: Laemmle Royal, Santa Monica; Laemmle Town Center 5, Encino

Movie Reviews

My Sunshine: Jesus director returns with poetic ice-dancing drama

4/5 stars

Rarely has figure skating been shown as so pure, poetic and sensual than in My Sunshine, Hiroshi Okuyama’s feature about two young ice dancers and their coach over one winter in a small town in Hokkaido, in Japan.

Filmed in the classic four-by-three screen ratio and boasting a desaturated colour palette which gives everything a dreamy quality, My Sunshine revolves around Takuya (Keitatsu Koshiyama), a stammering boy who is as awkward at sport as he is with his speech.

Bad at school in both baseball and ice hockey, the boy finds himself captivated by figure skating – or, specifically, the elegant star skater Sakura (Kiara Nakanishi). His perseverance in trying out pirouettes is noted by the girl’s coach Arakawa (Sosuke Ikematsu), who gives the boy proper skates and then private lessons.

Sensing a prodigy in the waiting, Arakawa begins to train Takuya alongside Sakura to compete in a pairs skating competition. Through this, the man rediscovers the joie de vivre he seems to have left behind after his retirement and relocation to the rural hinterlands.

Teasing natural and dynamic turns from his cast – with Sosuke looking very much the part with his smooth moves on the ice – Okuyama delivers scenes that ooze youthful energy and human warmth.

In the film’s pièce de resistance, a scene depicting Takuya and Sakura’s full routine, the duo glide gracefully across the ice, their breathing and the crisp glissando produced by their skates saying much more about their emotions than words ever could, whether about their dedication to the sport or the unarticulated feelings bubbling within each of them.

But My Sunshine is not all sweetness and light. Its descent towards tragedy is perhaps prefigured by Okuyama’s frequent positioning of his characters as small dots in vast spaces – an allusion, perhaps, to how their fates are somehow shaped by unspoken social forces they could not control.

And it is exactly such tacit norms which will eventually snap the trio’s growing bond.

Eschewing melodrama, Okuyama simply hints at the prevalent conservative attitudes in the town, the disapproval of Arakawa’s private life never really breaking into the open beyond one single word Sakura throws at her erstwhile mentor.

It is an altercation that is as brief as it is heartbreaking, and it speaks volumes about Okuyama’s deftness in evoking such emotions through his very economical storytelling and stylistic rigour.

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoSkeletal remains found almost 40 years ago identified as woman who disappeared in 1968

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoIndia Lok Sabha election 2024 Phase 4: Who votes and what’s at stake?

-

Movie Reviews1 week ago

Movie Reviews1 week ago“Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes”: Disney's New Kingdom is Far From Magical (Movie Review)

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoUkraine’s military chief admits ‘difficult situation’ in Kharkiv region

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTales from the trail: The blue states Trump eyes to turn red in November

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoBorrell: Spain, Ireland and others could recognise Palestine on 21 May

-

World1 week ago

World1 week agoCatalans vote in crucial regional election for the separatist movement

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoNorth Dakota gov, former presidential candidate Doug Burgum front and center at Trump New Jersey rally